As the push for independence swept through the Spanish colonies, it was largely led by criollos—people of pure Spanish heritage born in the New World. Yet the land and opportunities available in the Americas drew European immigrants of various backgrounds. Though strict Spanish class divisions made upward mobility difficult for those not of pure Spanish blood, there were exceptions—perhaps none more notable than the illegitimate son of an Irish immigrant who led Chile to independence and became its first post-monarchy leader: Bernardo O’Higgins.

Early Life

Bernardo O’Higgins’ unlikely path to liberating Chile from Spanish rule began in 1778 when he was born in Chillán, Chile. O’Higgins was the product of an affair between Isabel Riquelme, teenage daughter of a wealthy landowner, and the much older Ambrosio O’Higgins, who never married. The elder O’Higgins was born in Ireland and had moved to Spain in his 30s before ultimately traveling to the Spanish colonies and joining the ranks of the Spanish army. He did not formally recognize Bernardo as his son, but did provide for his upbringing. As a result, Bernardo originally used his mother’s last name. He was raised by her family as well as various friends and contacts of Ambrosio before moving to Lima, Peru and then, in 1791, to Cádiz, Spain and London to pursue an education.

In 1801, Ambrosio, who had ultimately become the Viceroy of Peru (which included present-day Chile) withdrew his support from Bernardo, who he accused of sedition and conspiracy, presumably due to some of the anti-monarchy contacts he had made while in Europe. Yet, later that same year, he formally recognized his son on his deathbed, leaving him a large estate, las Canteras, near Chile’s frontier with Mapuche territory. Bernardo, who was at this point penniless and struggling in Spain after nearly dying of yellow fever, then returned to Chile as a new member of the landed class.

Spanish Colonies: Independence Fever

By the early 19th century, the Spanish Empire, stretching from the present-day southwestern United States to the southern tip of South America, was starting to show cracks. As in the US just a few decades earlier, citizens were growing frustrated with trade restrictions and taxes imposed by the monarchy, coupled with the crown’s dismissal of criollos in favor of “pure” Spaniards from Europe when it came to positions of power in the colonies.

As Spain fought its own wars of succession in the 18th century and then became embroiled in Napoleon’s European wars, it necessarily altered and then lessened its presence in the colonies. When Napoleon invaded Spain and imprisoned its king, management of the entire empire fell into chaos. Colonists felt no loyalty to Joseph Bonaparte, who Napoleon had put on the throne, and could no longer rely on the Spanish government to help administer the colonies. While there was not yet a powerful movement advocating complete independence from Spain, a number of colonies formed juntas to govern in the king’s absence; it spelled the beginning of the end for Spanish rule.

O’Higgins’ Rise to Fame

During his time in Europe, O’Higgins had connected with Francisco de Miranda, Venezuela’s independence leader, and other “radicals” of the time who were advocating the colonies’ independence from Spain. On his return to Chile, he maintained contact with many such rebels who had since moved to Buenos Aires, continuing to develop his liberal ideals and support for colonial independence.

O’Higgins’ earliest days on the continent were spent organizing affairs at his new estate. Though he had no title due to the circumstances of his birth, he still had his father’s name and connections, which led him into positions of authority rather quickly. In 1805, he was named mayor of Chillán and established a friendship with an important political figure, Juan Martínez de Rosas, who would become his mentor. Acting as Martínez de Rosas’ representative, O’Higgins began participating in the newly established junta government in 1810.

As Spanish rule floundered, Chile’s ruling class quickly divided into three camps: extremists—ultimately patriots—who wanted complete independence, moderates who favored a slower pace of reforms and the maintenance of some connection with Spain, and royalists who remained loyal to the crown and preferred to uphold the status quo. Ultimately the extremists won out, but not without drawing the attention of the Spanish leadership in the Viceroyalty of Peru, which moved to bring Chile into line.

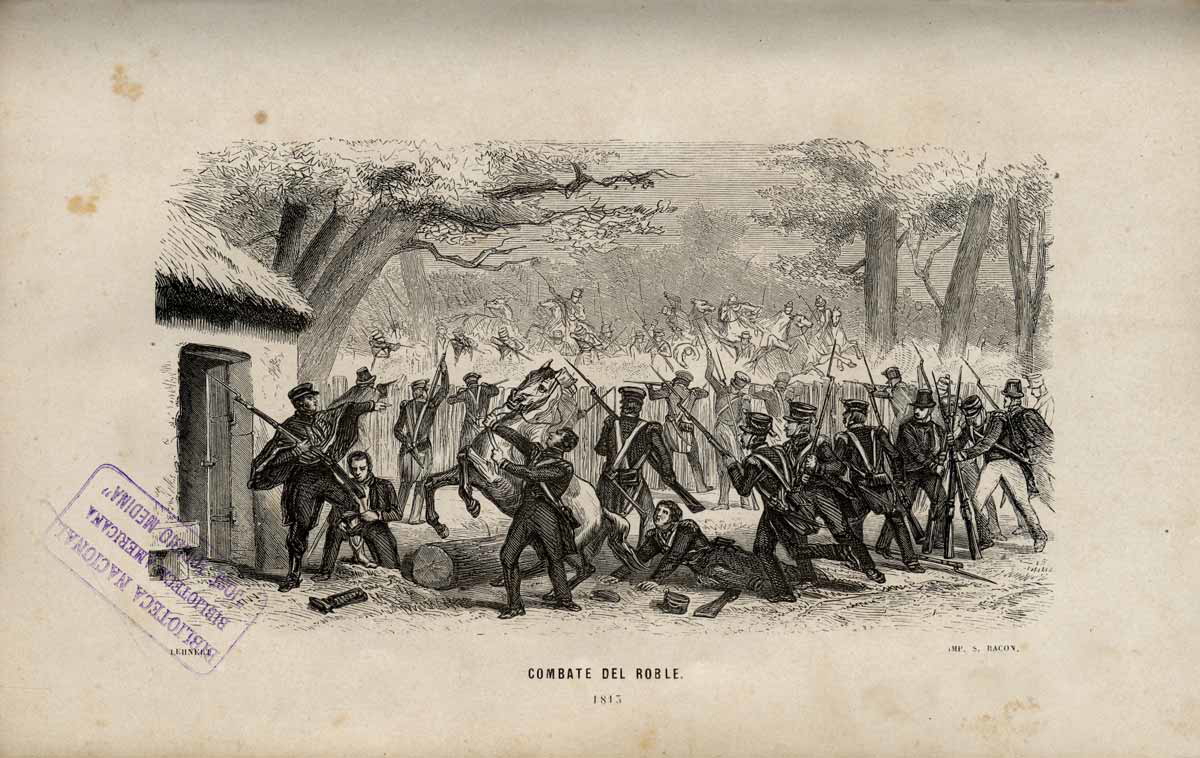

When the Spanish invaded Chile, O’Higgins took up arms. Though he had no formal military training, he quickly stood out among other officers for fighting alongside his men. In particular, his refusal to retreat at the Battle of El Roble in 1813, when José Miguel Carrera, leader of the patriot cause, fled, was heralded by the rebels. O’Higgins won the battle—as well as a new enemy in Carrera when many patriots looked to O’Higgins as their new leader.

Liberating Chile

After a number of losses, new troops from Lima arrived and the Spanish royalist forces retook Chile. O’Higgins and the other patriot leaders were exiled to Mendoza, in present day Argentina, but had no plans to give up the cause. José de San Martín, famed hero of the continent’s wars of independence, was leading Argentina’s patriots at that time and viewed O’Higgins, rather than Carrera, as leader of the Chilean rebels. Together they planned to retake Chile by bringing the Army of the Andes across the mountain range to join Chilean patriots and engage the royalists, a monumental task.

In 1817, they succeeded in traversing the treacherous Andes, though they lost many men as well as horses to the terrain, freezing temperatures, and illness. Undeterred, on February 12, the approximately 3,500 rebels encountered the 2,000-strong royalist army in Chacabuco, just north of Santiago, and won. Histories diverge slightly at this point, with some historians claiming that San Martín declined the position of Supreme Director and suggested O’Higgins in his stead while other scholars suggest the patriots themselves insisted the new Chilean leader be Chilean. Whatever the truth, O’Higgins was named Supreme Director, the highest position in the fledgling nation, while the war raged on.

Royalist forces, particularly in the southern part of the country, still needed to be quashed, so both San Martín and O’Higgins continued to fight. After one particularly violent battle, in which O’Higgins was shot in the elbow, rumors spread that both rebel leaders had been killed. O’Higgins, still recovering from his injury, hurried back to Santiago to stave off any other patriots who might have their sights on ruling in his stead. On the one-year anniversary of the victory in Chacabuco, O’Higgins formally declared Chile’s independence, though skirmishes with remaining royalists and Spanish troops continued.

Founding a Nation

Though Chile had declared itself an independent nation, the continued presence of the Spanish authority in Lima was a thorn in O’Higgins’ side; he felt that independence couldn’t be assured as long as that threat lingered. Though the country he now ruled was essentially in ruins after years of war, O’Higgins largely focused his early leadership on efforts to establish a naval force to counter the Spanish and depose the Viceroy, which San Martín succeeded in doing in 1821.

Domestically, O’Higgins embarked on various reform projects, hoping to rebuild Chile into a modern, less-stratified society. He built primary schools, reopened the national library and created a military training school. He established trade relations with European nations in the hopes of refilling the nation’s coffers and encouraging immigration to Chile.

However, some of his reforms won the ire of the aristocracy, particularly the abolishment of primogeniture and noble titles. He may also have played a role in the execution of his rival Carrera and his brothers, all of whom tried to overthrow or derail O’Higgins’ rule, though it was never proven. As the country rebuilt, he continued to be plagued by challenges and threats from Carrera’s supporters, remaining royalists, the elites, and the Catholic church. In addition, Chile’s financial situation was slow to improve, forcing him to take on the nation’s first foreign debt, a loan from England.

Though a resurgence of Spanish forces was no longer a danger, O’Higgins’ rule was now threatened from within. As he lost support, the country neared civil war, and former allies moved against him. Rather than fight another battle, O’Higgins decided to step down. In 1823, he fled to Peru with his mother, half-sister, and illegitimate son, Demetrio.

Legacy

O’Higgins spent the rest of his life in Peru, living in relative obscurity on land he was given as a “thank you” for helping win the country’s independence. He was briefly in contact with famed liberator Simón Bolívar, who requested his assistance in fighting the Spanish, but when he joined Bolívar’s forces, he found no leadership role available to him and soon returned to his quiet life in Peru.

When patriot forces did retake Peru, O’Higgins attended a celebratory ball where he toasted Bolívar and declared, “America is free. From now on General O’Higgins does not exist; I am only Bernardo O’Higgins, a private citizen.” Tragically, when he was finally granted permission to return to Chile and began making plans to do so, he fell ill. He died on October 24, 1842, still in Lima; in 1869 his remains were returned to Chile.

Today, O’Higgins is considered one of Chile’s founding fathers, and his accomplishments are honored in his home country and beyond. While Chile has graced everything from towns to national parks to military bases with his name, statues and sculptures of the revolutionary can be found throughout South America and as far away as England and Ireland. Though his years in power were short, his pivotal role in winning his country’s independence and early attempts to modernize its society have never been forgotten.