The New Testament Gospel of Matthew highlights Herod the Great as the villain who ordered the murder of all Jewish boys under two years old in Bethlehem in an attempt to kill Jesus. While this incident is not recorded elsewhere in history, it agrees with Herod’s violent, impetuous, and paranoid character. Though his legacy is shrouded in the horror of his brutality, few in Israel’s history matched Herod’s political and architectural genius.

What Was Herod’s Ethnicity?

The term Jew today is used to denote both an ethnic and a religious identity. In contrast to most ethnic identities, a person can “become” a Jew through religious conversion. Herod’s Jewishness, thus, is a matter of perspective. Ethnically speaking, Herod was an Idumean. The Idumeans were a group that was traditionally connected to the descendants of Esau who lived on the western edge of the Arabian Peninsula. Herod is sometimes described as an “Arab” in commentaries and encyclopedias for this reason. However, this description is somewhat anachronistic. While Herod was indeed from Arabia, this region was home to many ethnic groups in Herod’s day including many Jews. It is more accurate to use the specific term Idumean to describe him.

He Was a Religious Jew

Though Herod was not ethnically Jewish, his parents had converted to Judaism before he was born, and Herod himself was raised according to Jewish custom. The Jewish historian Josephus portrays the conversion of the Idumeans as having been forced upon them by the Hasmonean conqueror John Hyrcanus. However, there is evidence that Herod’s family took their new religion seriously. In fact, some historical sources say that Herod’s family descended from Jews who had settled in Idumea after the Babylonian Exile, though Josephus denies this. In any case, it is accurate to describe Herod as Jewish religiously and Idumean ethnically. Judaism had long accepted and even encouraged conversion as a bona fide path to becoming Jewish before Herod’s day.

However, the Jews’ hope for their political future depended on their having a king in the biological line of David on the throne in Judea. Thus, Herod’s mixed ethno-religious identity would complicate his political career considerably later in life when he finally became “King of the Jews.”

Herod Was the Son of a Shrewd Politician

Understanding Herod’s political position involves looking back to around a century before his birth, when Judea was under the thumb of the Seleucid Greeks. At that time, Jewish fighters under the leadership of a priest-warrior named Judas Maccabaeus struggled to free Judea from their Seleucid overlords in the Maccabean Revolt. Josephus records that, toward the beginning of this conflict (around 161 BCE), Judas Maccabaeus personally sent a delegation to the Roman senate to request a treaty, and Rome accepted. The revolt continued until 134 BCE when the Judeans finally won independence.

Afterward, Judea was ruled by a line of priest-kings called the Hasmonean Dynasty. Rome loomed large over Judean politics during this period, as well that of Judea’s neighbors. Herod’s father, Antipater I—or “Antipater the Idumean”—was governor of Idumea under Hasmonean rule. Because of tumult within the Hasmonean royalty and the Hasmonean’s troubled relationship with Rome, navigating this position required exceptional political acumen. Antipater was also a skilled military general. Herod would inherit both of these talents.

His Father Set Herod Up for Success

Herod’s father navigated challenging political transitions after the Roman general Pompey conquered Jerusalem in 63 BCE. At this time, two Hasmonean princes were vying for the throne of Judea—and both petitioned Rome for help. Pompey was sent to quell the civil war, but as each of them tried to curry favor with him, Pompey grew dissatisfied with both and decided to simply subjugate Judea to Rome.

Antipater deftly shifted his loyalty from the Hasmonean kings to Pompey. He later shifted his loyalty again to Julius Caesar when Caesar defeated Pompey an inter-Roman civil war in 47 BCE. These calculated moves put Antipater at odds with Hyrcanus II, the Hasmonean king in Judea (who served as a reluctant satellite ruler for Rome). By playing to Rome’s interests, Antipater was setting his son up for political success later on.

Herod’s First Governorship Was in Galilee

Mark Antony made Herod governor of Galilee in 41 BCE and gave his older brother Phasael the same position in Judea. This put Herod in a strategic yet precarious position. On the one hand, he was from an established and proven family in the sight of Rome. But on the other hand, the Jews whom he governed had grown increasingly resentful of Roman rule.

Elected King of The Jews by the Roman Senate

When the Western-Iranian Parthians under the leadership of Barzapharnes invaded the Roman province of Syria—of which Judea and Galilee were both strategic parts—in 40 BCE, both Hyrcanus II and Phasael were captured, and Phasael committed suicide. The Parthians installed Hyrcanus II’s anti-Roman nephew Antigonus II Mattathias in Hyrcanus’s place. Hyrcanus II was exiled to Babylon.

Herod, meanwhile, had chosen to flee in order to look for help. He went to the Nabateans, who refused him, and then to Egypt to appeal to Cleopatra. But eventually he decided to go directly to Rome. This proved a pivotal choice, for while he was there the Roman senate elected him to be King of the Jews instead of reinstating Hyrcanus II—or anyone of Jewish blood!

Herod then proceeded with his own Galilean soldiers and Rome’s full military backing to return to Judea as its new king—and conqueror. He deposed Antigonus II and took his throne.

Herod Was an Unpopular King

In the eyes of devout Jews, Herod had no legitimacy as their king. A king, in their view, needed to be in the line of David. But even more basically than that, he at least at to be a Jew by blood. Despite evidence that Herod participated fully in Jewish religious practice, he would never have been able to gain legitimacy in the eyes of his nationalist subjects.

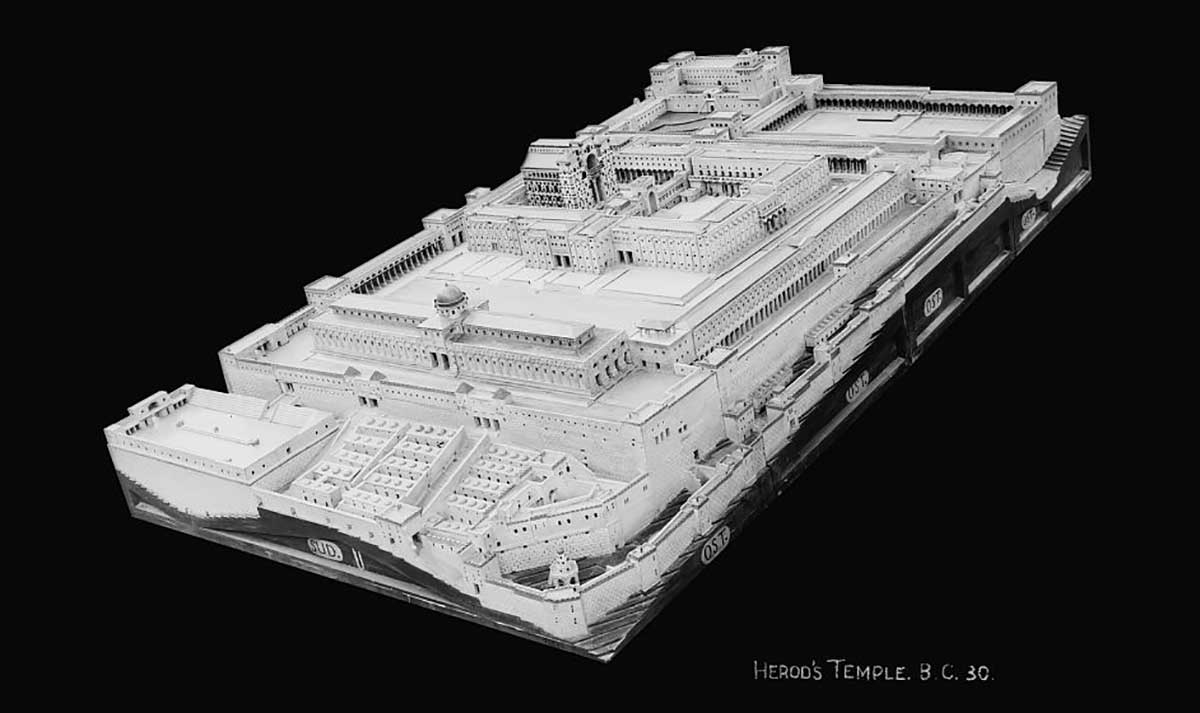

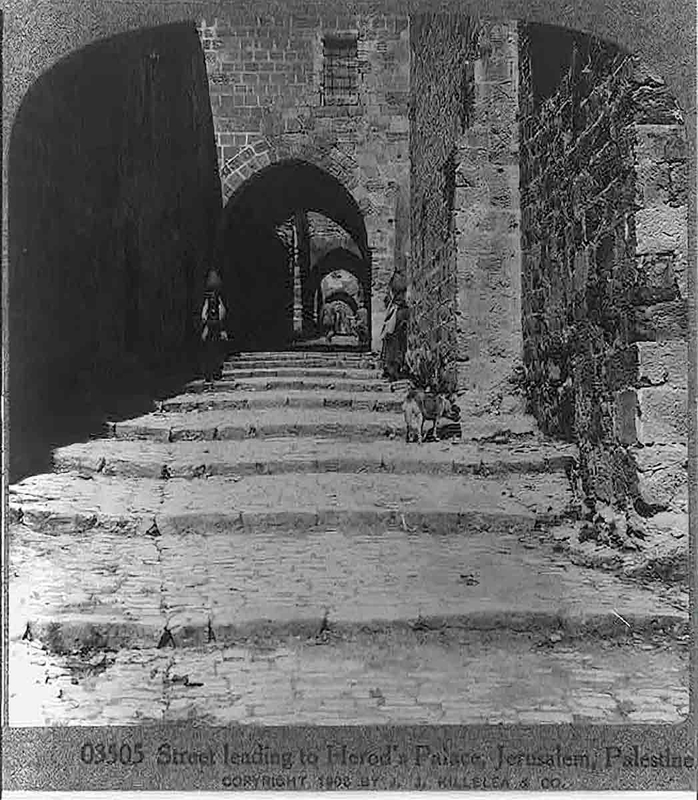

Herod would later try to prove himself to his Judean compatriots by rebuilding the Temple of Solomon. He made it into one of the most glorious buildings in the ancient world. Herod’s other architectural achievements were among the Mediterranean region’s most magnificent. Among these are his renovations at Masada, his ingenious artificial port at Caesarea, and the fortress called the Herodium where, it was recently discovered, Herod located his own tomb.

He Was a Cold-Blooded Ruler, and a Brilliant Politician

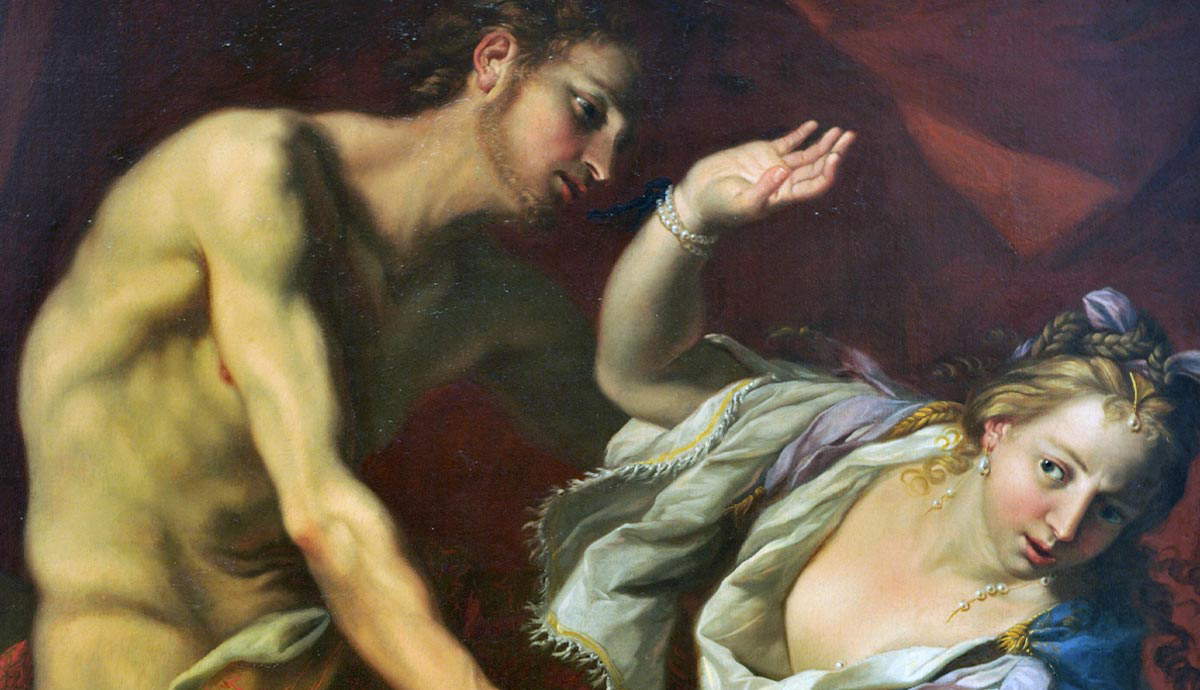

Herod is remembered most widely as the man who commanded Jewish baby boys in Bethlehem to be killed. Whether or not this event occurred is a matter of debate among historians. However, that Herod was capable of arbitrary violence is not. Toward the end of his life, Herod commanded the execution of many of his own family members out of fear for his throne, including his second wife Marianne and her two sons. His legacy is enshrouded by this and other similar acts of fear-driven cruelty.

Yet whether before or after his lifetime, Judea probably never knew a more savvy and ambitious politician. While political astuteness is hard to measure, Herod’s architectural prowess left clear evidence of his genius. In this area, he was unmatched by his contemporaries. He was brutal, probably mad, and certainly complicated. But he was also a fascinating personality with exceptional abilities.