In 896, Pope Stephan VI called the “Cadaver synod,” a council made up of high-ranking leaders of the Catholic Church, to try his predecessor, Pope Formosus. The charge: attempting to usurp the papal throne. If found guilty, Formosus would be excommunicated. Despite the seriousness of the charges made by his successor, Formosus sat perfectly still. Maybe it was because he had been put on trial before. Maybe it was because he knew he was innocent. Or maybe, just maybe, it was because he was dead.

The Successors of Charlemagne

To truly understand how the corpse of a pope was exhumed and put on trial by another pope, it is important to first understand the role the highest office in the Catholic Church played in medieval politics. At this time, the ruler Charlemagne was at the height of his power. He was the most powerful ruler in all of Europe, and as such, many popes sought to shore up their own power by aligning themselves with him. When Pope Leo III ascended to the leadership of the Church, he took it a step further by crowning Charlemagne the first Holy Roman Emperor in 800.

While the move helped to solidify Leo’s position and stabilized the Church at a particularly fractious time, it also inserted the papacy into the exceedingly messy world of medieval politics for hundreds of years. With the pope now a designated kingmaker, ambitious and powerful rulers from across Christendom would attempt to influence the pope in numerous ways, and more often than not, this included force of arms. This pattern was already well in place when a young noble with the odd name of Formosus was born in Rome.

Formosus’s Formative Years

While evidence of his early life is sketchy at best, he was most likely born in 816 and was a member of an influential Roman family. What he did during the first 50 years of his life is anyone’s guess, and there are nearly no reliable sources that have survived today, but it is a safe bet that he either chose or was pushed onto the path many popes of his day followed by entering the clergy at a very young age.

In 864, he became the Bishop of Porto, an ancient city that lay just north of Rome in a very strategic place where the Tiber River emptied into the Mediterranean Sea. This appointment marked his ascension to a more influential level within the church as he was soon being sent by the Church to serve as a personal representative of the pope in parts of Europe that were just starting to come under the influence of Christianity, and none were more important than Bulgaria.

Fortune Turns for Formosus

Formosus arrived and found the state of Christianity in Bulgaria to be somewhat bizarre. Folk beliefs like the casting of magic rocks had integrated their way into the Bulgarian church, so Formosus got to work straightening out, and he apparently did very well too, because within a year, he was converting masses of pagans, building churches, and even appointing bishops. The ruler of Bulgaria, Boris I, was so impressed that he even suggested that Formosus become the head of a new Bulgarian wing of the Church.

This was where the trouble began, because in creating church offices and consecrating new churches, Formosus had done so without the approval of the Pope. To make matters worse, many of the bishops he appointed were later accused of simony, or selling either church offices or blessings, accusations that would come back to haunt him later. Soon, Formosus was recalled to Rome, eventually finding himself sent off to France, where he was put in charge of the mission that told Charles the Bald, Grandson of Charlemagne, that he was to be crowned Holy Roman Emperor. However, after his coronation on Christmas Day in 875, Formosus soon soured on the entire idea and led a faction in opposition, and this proved to be the straw that broke the camel’s back.

Pope John VIII called two separate synods that heaped all sorts of accusations on Formosus, including power-grabbing, looting the cloisters of Rome, and plotting to overthrow the papacy. Reading the writing on the wall, Formosus hid in the South of France for six years until John VIII died and his successor, an ally, cleared him of all charges and brought him back to Rome, where he was able to regain his prestige and eventually position himself as a dark horse candidate for the papacy.

Pope Formosus

The election of Formosus to the papal office was a surprise to everyone, probably including Formosus, as he was not one of those favored to win the election. Sources indicate the papal election of 891 was a tumultuous one where two factions, one supporting Formosus and the other supporting a cardinal named Stephan, nearly came to blows. Eventually, Formosus won out, but Stephan was so bitter from the ridicule he received that he swore revenge. Formosus, meanwhile, set to work right away, dealing with many of the most pressing issues in the church.

If there were Catholic awards for trying, Formosus would probably have won a blue ribbon. Despite his surprise election, he proved to be an independent and strong leader who set to work making many much-needed reforms to the church. He worked to combat nepotism and strengthened rules regarding conduct for officials within the Church. However, he also inherited the political issues that plagued his predecessors, and soon he was embroiled in them as well.

The Two Emperors

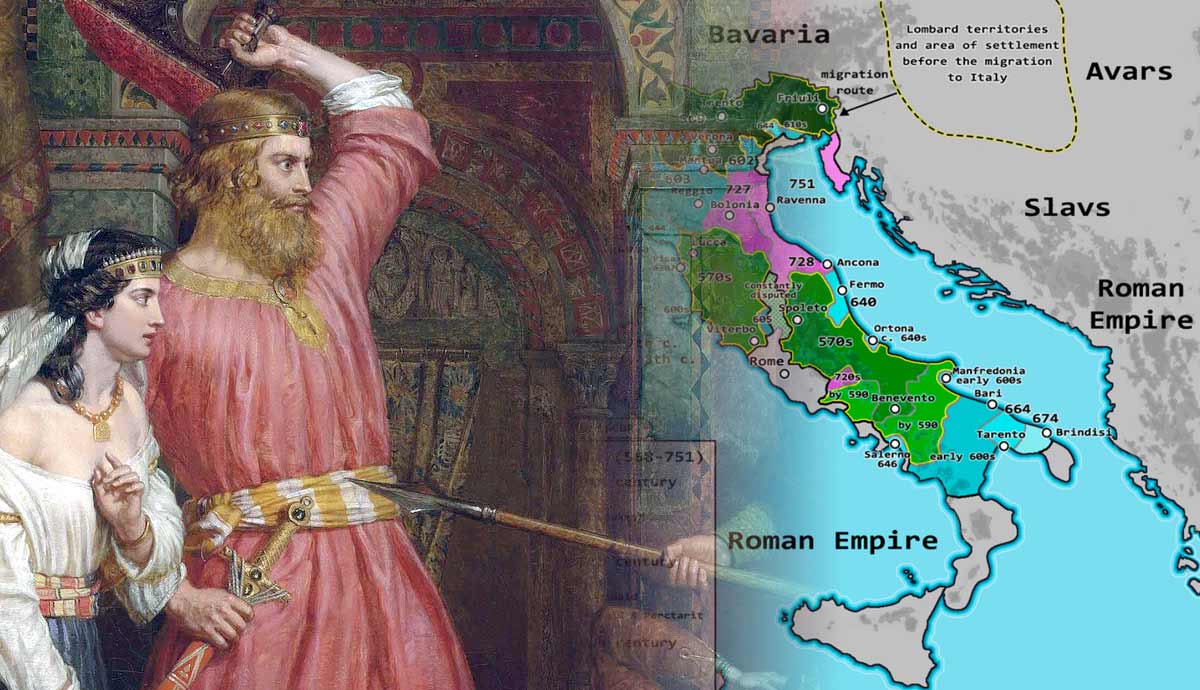

In keeping with tradition, Formosus had conferred the crown of Holy Roman Emperor to an Italian Duke named Wido of Spoleta, sometimes also known as Guy III. But in reality, the endorsement of the crown on Wido’s head was done at swordpoint. Wido had amassed a large army and muscled his way into Italy, where he occupied not just the countryside but also Rome itself. Formosus, under occupation, had little choice but to support Wido as ruler, but the crafty pope had his own plan.

He sent secret overtures to another regional ruler named Arnulf of Carinthia, asking him to liberate Italy and, in exchange, become the Holy Roman Emperor. Arnulf agreed, and after a series of battles and an epic crossing of the Alps, he arrived in Rome in 896. After taking the city by force, he was received with what historians recorded as “great fanfare,” and Formosus crowned him Emperor.

This mutually beneficial arrangement was short-lived because after Arnulf marched off to deal with Wido’s son Lambert. Formosus died only five weeks after placing the crown on his head and was soon buried. However, he wouldn’t stay that way long.

The Return of Stephan

Before Formosus’s body even had time to cool, his old rival Stephan went to work. The successor of Formosus, pope Boniface VI was either killed or driven from office within two weeks of his appointment and soon Stephan VI was able to take control of the papacy with a little help from Lambert, the son of the Emperor that Formosus had helped depose, and both men were united in their hatred of the now dead pope.

In January of 897, Stephan VI ordered the corpse of Formosus dug up and posthumously put on trial. A synod was convened in the Lateran Palace, and the body of the late pope was propped up so that it could stand trial. Not wanting to be perceived as unfair, Stephan appointed a deacon to speak on behalf of the putrefying corpse sitting in its burial robes.

The church officials who gathered all commented at great length about how ghastly the entire affair was. Stephan railed at the corpse, accusing it of all sorts of outrageous crimes, including simony, supposedly while blood dripped from its mouth. But nothing, not even the increasing disapproval from the crowd, stopped his tirade. According to legend, at one point, a full-on earthquake struck the Basilica in the middle of the trial, a sign that many in the audience took as disapproval from the almighty himself, but even the hand of God would not sway Stephan that perhaps the whole thing was a bad idea.

Unable to defend himself due to being dead, the guilty verdict was all but certain, and soon the pope’s rotting corpse was stripped of its burial vestments and thrown into the Tiber, much to the satisfaction of Stephan IV. However, he had gone too far.

Powerful church officials, as well as influential members of society, were outraged at the treatment of the dead pope. The whole affair was such a scandal that even Lambert backpeddled, eventually restoring Formosus’s status and even condemning the actions of his ally Stephan. A level-headed monk had fished the pope’s corpse from the river and hid it, so Formosus was re-interred in St. Peter’s Basilica with full honors. In fact, after Stephan was eventually imprisoned and most likely murdered, another synod was convened to try and scrub the entire situation from the papal history books altogether.

It is sad that Formosus is remembered today more for what happened after he died rather than his accomplishments when he lived. He was a just and courageous spiritual leader at a time when many popes were anything but. He was a stalwart protector of church independence who made admirable progress against nepotism, simony, and many other issues that compromised the authority of the early Church. The fact that he was martyred and restored thanks not to his own efforts, but instead to the outcry of the faithful, is a reminder of the influence and importance that church members continue to have to this day.