Long before the arrival of European explorers and colonizers, the lands that made up what would become known as the New World were already home to huge, sprawling cities. Locations such as the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, the Incan city of Cusco, and the Mayan city of Tikal were home to immense buildings along with thousands of people.

Stories of these urban centers and the incredible wealth they contained drove more and more explorers to search far and wide for similar places in what would become the United States, but never finding any, it was assumed that none existed. The truth was that these explorers were just a few hundred years too late to see North America’s greatest city, now one of the greatest archaeological sites in the US.

Rediscovering America’s First Megacity

Long before the rise of Cahokia, the people who historians have dubbed “the Mississippian culture” had been living in the area for many years. The name Mississippian is a catch-all term used by historians for the diverse collection of tribes that lived in the area around the Ohio, Tennessee, and Mississippi river valleys, because in truth, we have no idea what they called themselves or the places where they lived. With no written or oral traditions to draw on, all that we know about the mysterious and enterprising people who would go on to build the great city of Cahokia comes from the archaeological evidence that has been painstakingly collected over time.

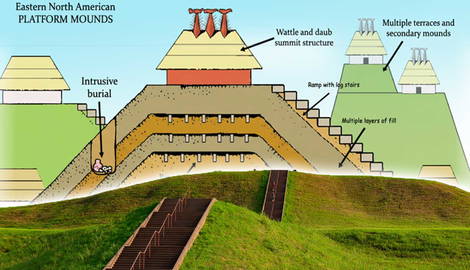

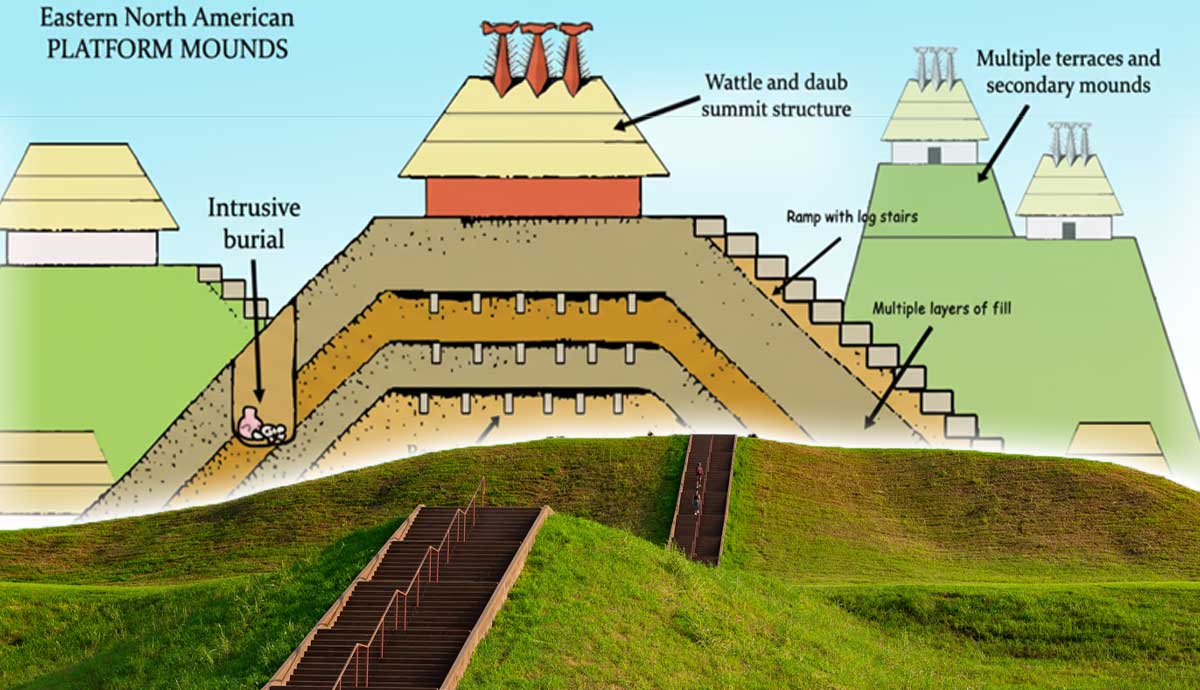

Mississippiian tribes lived across nearly a quarter of what would one day become the United States, where they had distinct cultural practices, grew and ate different food, and adapted their lifestyles to different climates and environments. But they did share one important cultural trait—they built large earthen mounds. Constructed mostly for religious or ceremonial purposes, constructing these mounds required a high level of social organization, centralized leadership, and a large population to draw labor from—all elements that need to be in place in order to give rise to cities.

The Rise of Cahokia

Around 700 CE, the area that would one day become Cahokia was just another small agricultural village. Centuries of growing foods like sunflowers and squash had allowed the people who lived there to perfect the agricultural practices that would be key to creating the food surplus that would support the massive populations within a city, but these crops weren’t what would be considered high-yield. The foodstuffs needed to turn Cohokia from a village into a megacity would come from one of the most essential foods of the Americas: corn.

By analyzing pollen samples recovered during excavations in the area, we know that by the year 900 CE, much of the land around Cahokia had been cleared of trees for agriculture and planted with corn. Within a few hundred years of the introduction of corn, which arrived in the area most likely through trading with indigenous groups living in the Southwest, the population of the area exploded. Thanks in part to years of generous rain, the number of people living in the area jumped to nearly four times its size within only about 50 years. As the size of the settlement grew, so did the complexity of society and the number of massive construction projects that would eventually give rise to Cahokia.

Cahokia Is Born

Many of the earliest construction projects here involved redesigning and reconstituting dispersed settlements into a single city. Evidence recovered through ground-penetrating radar shows how residential neighborhoods were relocated and converted for civic use or for expansive residences utilized by the elites. What was once a collection of villages arranged around central courtyards began to transform into a methodically surveyed and planned grid system reminiscent of modern urban centers.

In addition to these physical changes and expansions, there is also evidence of the establishment of an extensive trade network with Cahokia serving as a major hub. Items such as specific metals and decorative luxuries like beads made from seashells could only have been sourced from hundreds of miles away. At its height, this system of trade stretched from the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast, covering a full third of the present United States.

Much like a modern city, Cahokia also became home to migrants from cultures other than the Middle Mississippians. Evidence in the form of diverse burial practices as well as the naturally occurring isotopes housed in the remains of these people shows that as many as 30% of the residents of Cahokia were from cultural groups located far outside of the area.

Additionally, these people lived within a society where there were clear and stratified class differences, as evidenced by their diets and the elaborate burial practices that only some of the city’s residents were able to participate in. Burial sites for individuals that include hundreds of exotic goods are clearly those of high-ranking members of society, while burial pits with dozens of remains and few trade goods were most likely used for those who were enslaved or sacrificed.

All of these advances led to rapid population rise, which is estimated to be as high as 15,000 people, a population large enough to support equally massive projects like Cahokia’s most famous feature, Monk’s Mound.

Monk’s Mound

Mounds were incredibly important to the culture of the Mississippian people. They were places of worship, places for burial, and in some cases, places that could help chart the course of time, like Stonehenge. Of all the features that make up Cahokia, none is more impressive than the large central mound complex named Monk’s Mound after the French trappist monks who farmed the mounds’ terraces. Rising in height to the equivalent of a seven-story building, the mound features multiple levels and a base that is approximately the same size as the Great Pyramids of Giza.

Built in stages over the span of several centuries, the mound began as one of over 120 smaller mounds that would eventually be constructed at the site. Some of these smaller mounds we eventually incorporated into the large mound as Monk’s Mound grew to its final size around 1100 CE. The top level at one time had wooden structures on it, most likely used to support the spiritual life of the city.

Core samples pulled from the mound reveal two incredible things: that the structure is entirely made of soil and clay, and that this immense mound covering more than 13 square acres was constructed with nothing more than people and hand baskets. However, within a few hundred years of its completion, its architects would abandon the area and be lost to time.

Decline and Desolation

By the year 1200, Cahokia was at its height in terms of size and influence, but soon after reaching this incredible milestone the population began to rapidly crater and by about 1350 CE, the area was almost totally deserted. The reasons for this collapse are guesses at best, but the area around the city offers clues that point to several possible answers.

One theory is that increased flooding made the area untenable for farming or habitation. Cahokia was originally built in a floodplain, which provided excellent soil and ample access to water needed for farming, but this also made the area subject to periodic flooding. Over time, evidence shows that periodic floods became much more frequent and larger, inundating large portions of the city and forcing the migration of residents to other areas. It is unclear if this flooding was more due to a changing climate or a result of erosion caused by the clearing of trees to expand farmland.

Another possible cause might have been increased discord and violence, both from within the city and from forces outside of it. Around 1200 CE, there was a huge fire in one of the city’s residential areas, a sign of possible discord or revolt against what most historians believe was a highly stratified society with little ability for people to move between social levels. The buildings that were consumed were not rebuilt, but there is evidence of crude walls and palisades being constructed around parts of the area for the first time as the year of its final abandonment approached. This suggests that the remaining residents were either trying to protect themselves from each other, or perhaps seeing their numbers dwindle to levels that made them extremely vulnerable, were trying to defend themselves against some outside force, but there is no way to know for sure.

The depopulation of Cahokia corresponded with a wider trend in the region known as “the Vacant Quarter,” where permanent settlements almost totally disappeared and never again reached the size and scale of Cahokia. Groups of hunter-gatherers would periodically visit the area, but the people and the culture responsible for creating America’s first megacity disappeared and were absorbed by other indigenous groups.

Today, Cahokia and Monk’s Mound are designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site and have been incorporated into a state park visited by people from all over the world.