Josephine de Beauharnais was a consort, a courtesan, and even a prisoner, navigating these roles with her characteristic charm and resilience. However, her most lasting legacy isn’t her time as empress but her role as mother to Eugène, viceroy of Italy, and Hortense, queen of Holland, whose influence shaped the Napoleonic era and beyond.

Josephine’s Early Years

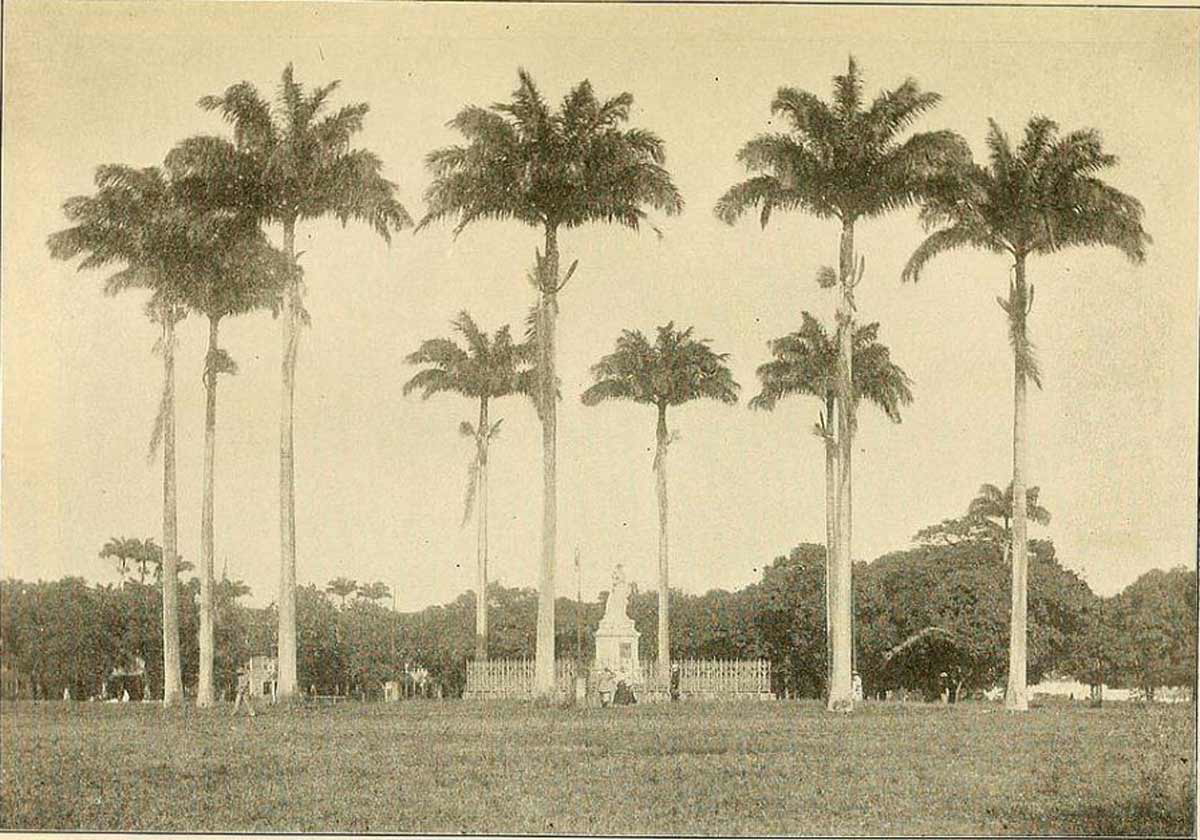

Josephine, born Marie-Josèphe-Rose de Tascher de La Pagerie, came into the world on June 23, 1763, at the Trois-Îlets sugar plantation in Martinique. Her family, though aristocratic in title, wasn’t exactly rolling in wealth. Josephine’s father, Joseph-Gaspard de Tascher, was an impoverished French navy officer who likely spent more time dreaming of better days than actually living them. Meanwhile, her mother, Rose-Claire des Vergers de Sannois, who brought her family’s wealth to the marriage only for her husband to squander it, did her best to keep up the airs of high society in their sun-drenched but far-from-opulent island home.

Little Josephine, affectionately called Yèyette, grew up amidst the hum of colonial island life. She certainly wasn’t set up for royal Parisian society in those early years. By all known accounts, she had a rather simple education compared to the girls that would eventually become her social equals. Convent schooling at Dames de-la-Providence in Fort-Royal starting in 1773 taught her the basics but it is fair to say she wasn’t cramming for philosophy exams.

One biographer cheekily informed audiences that Yeyette could read and write, but that was about the extent of her scholarly prowess. Her soft Creole accent and provincial manners didn’t exactly scream “refinement,” but fate has a funny way of taking the least likely candidates and turning them into legends.

Her idyllic island life was turned upside down when, at the age of 16, she was shipped off to France to marry fellow teen Alexandre de Beauharnais, a Martinique native and a well-bred aristocrat making a name for himself in France. His connections ran deep, not least because his father had a mistress who just so happened to be Josephine’s well-kept aunt. The arrangement was this lady’s idea, no doubt hoping to tighten the social ties between their families and their pocketbooks. Off Josephine went, sailing away from the Caribbean warmth into the cold, uncertain waters of French high society. But Josephine, young and inexperienced, didn’t quite make the splash both she and her husband hoped for.

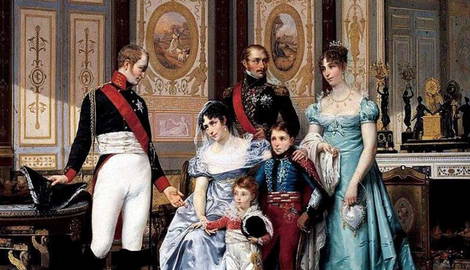

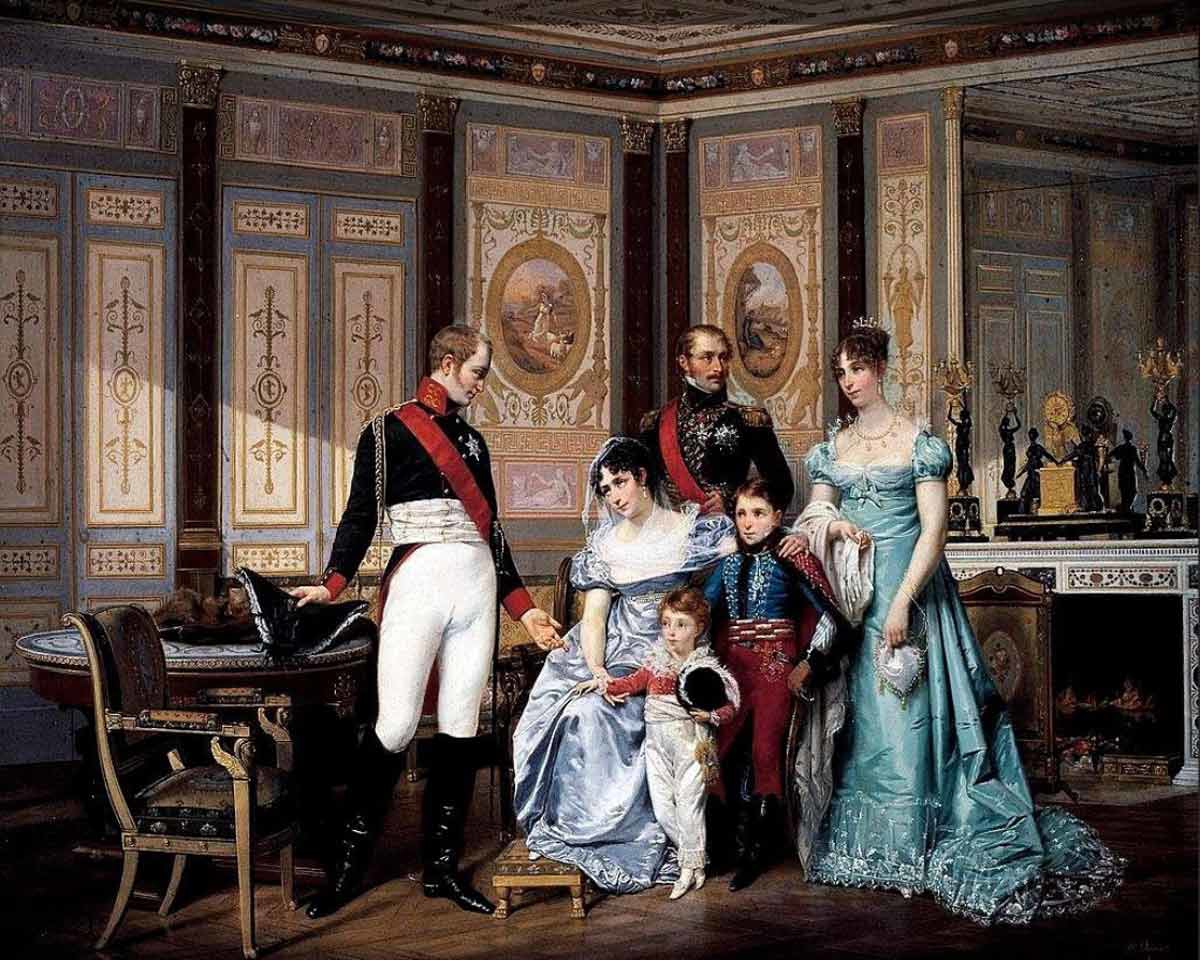

The wedding took place on December 13, 1779, in the town of Noisy-le-Grand, just outside of Cosmopolitan Paris. Alexandre, not thrilled to be married to a girl he saw as backward, was a man who clearly liked his freedom. Though Josephine gave birth to their first child, Eugène, in 1781, and a daughter, Hortense, followed two years later, family life didn’t seem to suit Alexandre. He took every opportunity to hop between Martinique, Paris, and wherever else his whims (and mistresses) took him. Josephine, raised far from high society, made the faux pas to care what her husband was getting up to.

1785 spelled the end of the marriage after six long years. Alexandre, possibly under the influence of one of his more demanding lovers, began hypocritically accusing Yèyette of infidelity. It is worth noting here that these accusations were laughably unfounded, but they had the desired effect of pushing Josephine into seeking a legal separation. Despite Alexandre recanting his statements in the courts, the legal union was dissolved. Alexandre graciously agreed to support Yèyette and the children financially—which is to say, he promised to provide funds but frequently and conveniently forgot to share the wealth.

Separated but determined not to return to Martinique with her tail between her legs, Josephine spent a few more years in France learning the fine art of keeping her and her children’s heads above water. She lingered in Paris, increasingly in debt, but brushing shoulders with the fashionable elite. With years of practice now bolstering her innate gifts, she was able to woo salons whose patrons found her charm irresistible. Her unconventional beauty, highlighted by her slightly olive skin and captivatingly dark eyes, turned heads even if her finances didn’t.

Eventually, the glamorous salons of Paris gave way to a brief return to Martinique in 1788, where she stayed for a couple of years to recuperate from the breakdown of her marriage and—as a strange dowry paid out later points to—possibly gave birth to an illegitimate daughter.

While her cousin Aimée disappeared at sea, later to become the favorite wife of a Turkish sultan (if the legends are to be believed), Josephine was poised to chart a far different course—one that would see her rise from the ashes of debt and single parenthood to become the first French empress in European history.

The Revolutionary Years

When the French Revolution kicked off in 1789, Josephine (going by Rose at the time, having put away her childhood nickname) found herself right in the middle of the chaos. Her ex-husband, Alexandre de Beauharnais, was a key player in the new political scene, becoming president of the National Assembly in 1791. It seemed, briefly, that the former couple would make nice and enjoy riding one another’s coattails as a new social order was established. After all, Alexandre had moved up in the world, and Josephine was no longer the provincial pumpkin she’d been at the start of their marital years.

However, the Revolution had a funny way of turning on its own, and Alexandre’s moment in the sun quickly darkened. In 1794, he was accused of being a royalist sympathizer (despite having sided with the people against the monarchy) and was thrown into prison. Josephine, who had also been arrested, was taken to the grim confines of Les Carmes, where she made some unforgettable friendships with fellow prisoners: a ragtag group of aristocratic women, all waiting to find out if they’d lose their heads, commiserating over their shared doom and swapping gossip. Josephine, a social butterfly even in the dank confines of a grossly overcrowded prison, formed close bonds with the likes of Grace Elliott, a Scottish spy, and Térésa Cabarrus, a revolutionary leader’s mistress.

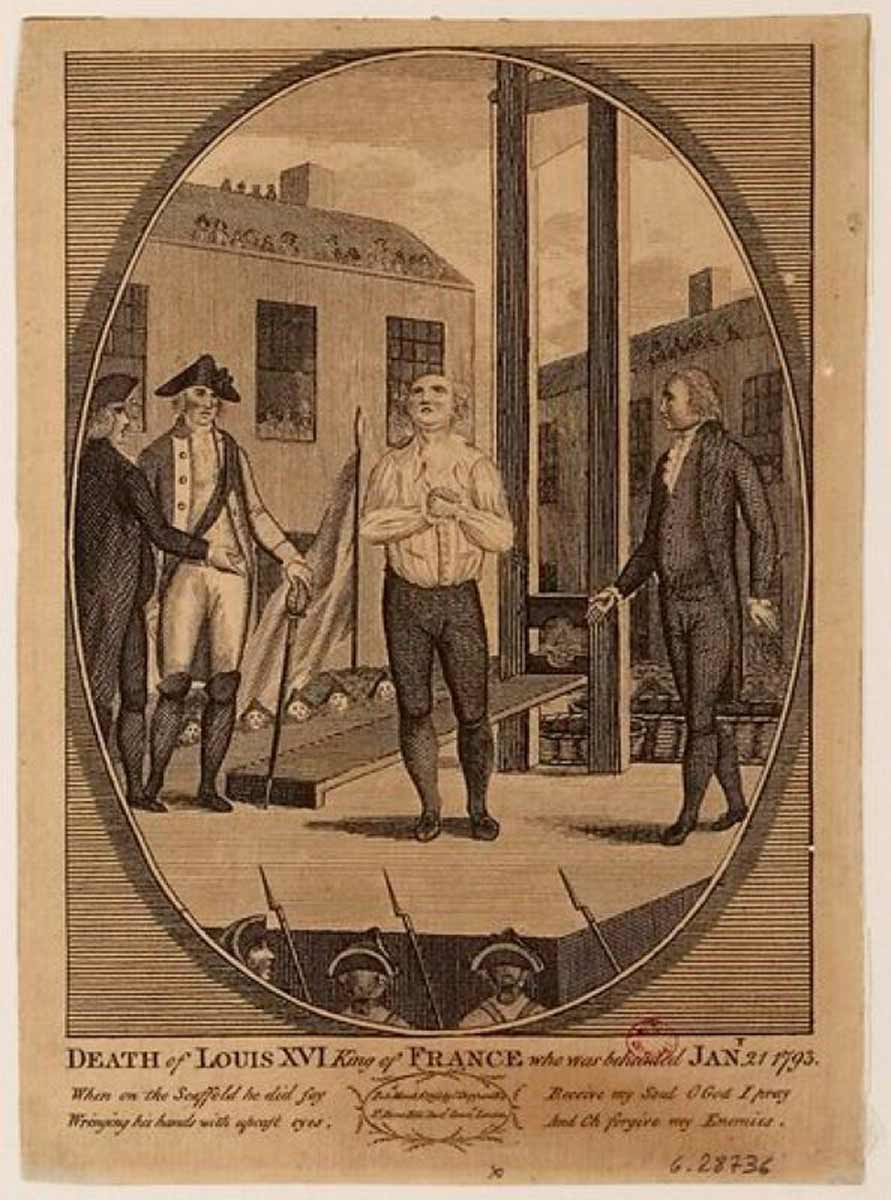

The Revolution had no mercy and in July 1794, Alexandre de Beauharnais was guillotined. A lock of his hair and a final letter were passed to Josephine. Though the letter was friendly, both Alexandre and Josephine had taken different lovers while imprisoned. His death sentence all but sealed her own fate, and for days, she slept on the cold floor, as the guards informed her she soon would have no need of a bed.

Josephine, preparing for her inevitable execution, chopped off her hair in a rough bob that would go on to inspire the iconic “coiffure à la guillotine” style. Like many prisoners, she feared her hair getting in the way of the blade and making an already terrible death even worse. The fall of Robespierre on July 28, 1794, saved her from the guillotine by a rumored mere day. Can you imagine the dramatic sigh of relief when a guard came to inform her that Robespierre had been the one to lose his head that day, not her?

After Alexandre’s execution and her miraculous escape from death, Josephine was left with two children, no foreseeable income, and quite serious emotional scars. She was also dealing with physical ones—prison life had not been kind. The malnutrition, illness, and general filth of Les Carmes had left her in rather poor shape. Her teeth, already in bad condition from her sugarcane-chewing childhood, were decaying rapidly, and she developed a nervous habit of hiding them with a handkerchief when speaking.

If history has taught us anything, it is that Josephine was nothing if not a survivor. Her star had risen and fallen more than once, and she knew how to play the cards she was dealt, even if those cards couldn’t make up a full hand. After her release, Josephine stayed in Paris and managed to finagle herself a relationship with Paul Barras, a wealthy military commander who was a major figure in the new post-Revolution government.

Becoming his mistress turned her fortunes around yet again—she moved to a fancy house, sent her kids to private schools, and began hosting lavish social events to cement her place in society and in order to put out feelers for when she would inevitably need a new rich protector.

Josephine’s Children

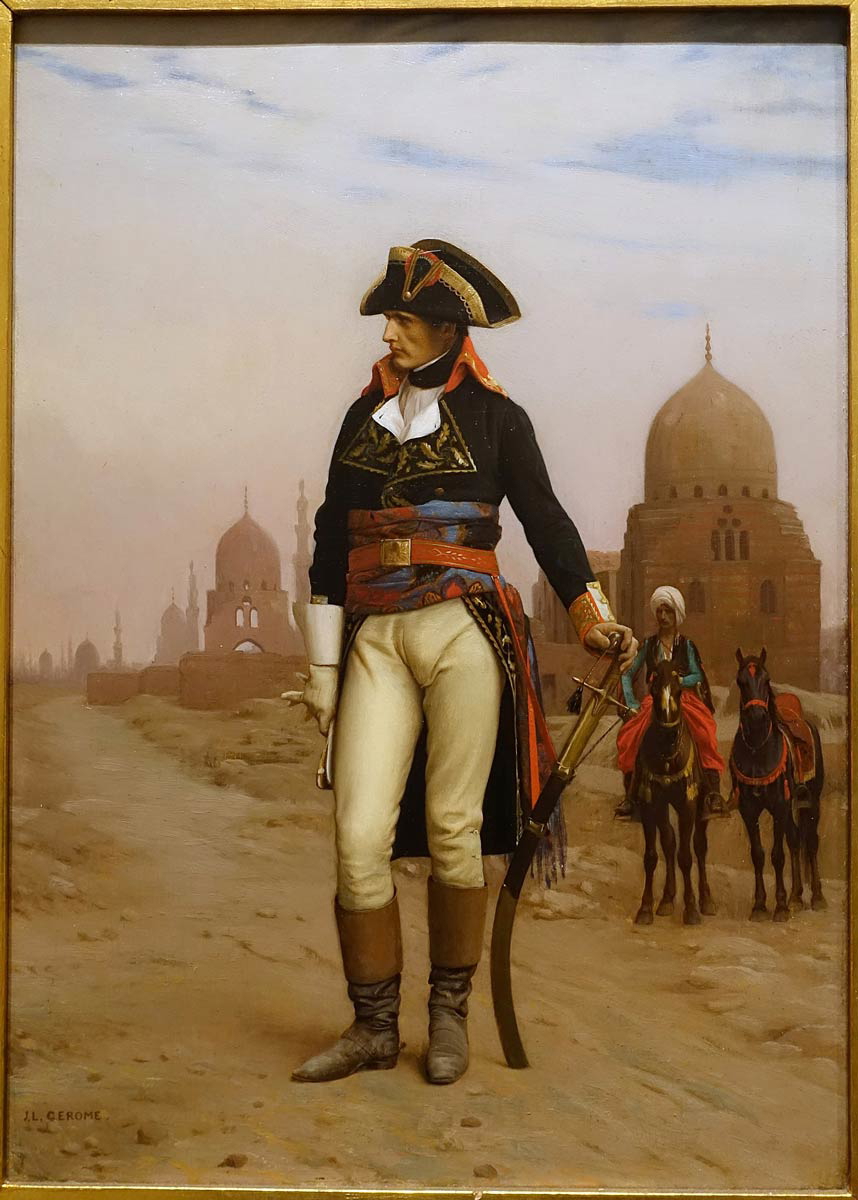

While Josephine’s son Eugene was busy apprenticing as a carpenter during the Reign of Terror—a skill that probably seemed practical with both parents facing a death sentence—Napoleon was off conquering Italy. Eugene decided to turn from furniture to soldiering, landing a spot in Masséna‘s division. By 1797, Napoleon was his stepdad, and he was bumped up to sous-lieutenant. He was also promoted to aide-de-camp. Eugene then followed his stepfather to Egypt, where his loyalty paid off with another high-paying promotion to lieutenant. At the Siege of Jaffa, he negotiated the defenders’ surrender smoothly, only to get smacked in the head by an explosion at Acre. He, and his mother and sister, were lucky he survived.

After Napoleon’s Egyptian misadventures, Eugene got promoted to prince as a “thank you” for taking such a hit and became Viceroy of Italy. He had an aristocratic title, a Grand Cross or two, and by 1806, he was formally adopted by Napoleon, making their bond as official as a stepfather-stepson relationship could be. Eugene also landed a royal match with Princess Augusta Amelie of Bavaria, initially arranged as a political alliance. However, the two young people fell in love and had no problem getting down to the business of heirs.

When Napoleon offered him the shiny title of prince of Venice, the Allies tried to tempt Eugene with a kingdom if he turned on his stepdad. Eugene declined, staying loyal to Napoleon despite some serious military headaches. Eugene found himself sandwiched between the Austrian forces and those of the backstabbing Marshal Murat. After Napoleon’s abdication, Eugene threw in the towel and retired to Bavaria to be with his wife’s family where, after years of warfare, family life probably seemed downright peaceful.

When Napoleon staged his 1815 comeback, Eugene stayed ensconced in Bavaria, politely declining the role of Peer of France. He had promised his father-in-law, King Maximilian, not to get involved in this new round of chaos. He spent his later years doing philanthropy, reaching out to Napoleon’s old soldiers who had fallen on hard times. Eugene died of a cerebral hemorrhage at 42, too young but having found peace and purpose.

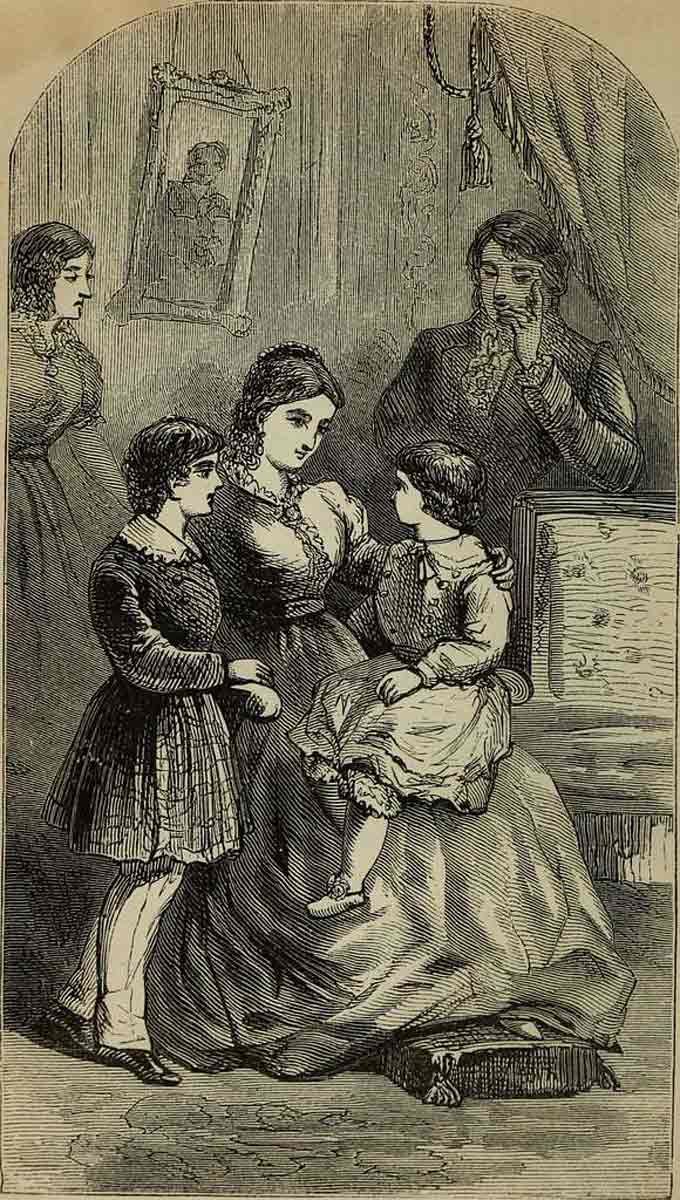

Eugene’s younger sister, Hortense, became Queen of Holland when Napoleon arranged her marriage to his brother, Louis Bonaparte. The union was as unhappy as a forced marriage could be, but it did produce three sons—one of whom would grow up to be none other than Napoleon III.

Hortense was more than just an ill-used consort, though—she was a composer, a painter, and a woman who found solace in her music and the arts. Her most famous composition, “Partant pour la Syrie,” later became the French national anthem under her son’s reign.

When Napoleon divorced her mother, Joséphine, in 1809 he refused to allow Hortense a divorce from Louis. A year later, the emperor finally agreed to a separation in 1810. Perhaps he gave Hortense this freedom as a gift since his stepdaughter had become good friends with the very woman who took her mother’s place, the 19-year-old Hapsburg princess who was Napoleon’s second wife.

It was around this time that Hortense had an affair with Colonel Charles de Flahaut, a man who undoubtedly had more charm than her husband. The result of this romance was a son, also named Charles, who would become the future Duc de Morny.

Hortense’s life had no shortage of drama as if that could be inherited as easily as hair color or height. After Napoleon’s defeat and exile in 1814, she found herself at the center of a mess of political intrigue.

Supporting Napoleon during his return for the Hundred Days didn’t exactly make her popular with the new regime, and she was promptly banished. Ever resilient, she packed her bags, settled in Switzerland at Arenenberg, and spent her remaining years writing, composing, and protecting her sons. Her memoirs, published between 1831 and 1835, offered a glimpse into her tumultuous life, filled with intrigue, romance, and plenty of tea about her infamous parents.

In her final years, Hortense’s home became a cultural hub, where she entertained guests like Franz Liszt and Lord Byron, composing music and painting until her death in 1837. She may have been exiled, but she certainly wasn’t withering away in loneliness. Her legacy continued on through her sons, particularly Napoleon III, who eventually became Emperor of France. Even though Hortense had her fair share of ups and downs, she left her mark on both French history and the European art scene.

Now, if you’re wondering whether Josephine’s line still carries on today, look no further than the descendants of Napoleon III’s illegitimate children (the comte Labenne and Conte di Orx)—there were certainly a few. Eugene may have been the dutiful son, and Hortense the artistic soul, but it was Napoleon III’s offspring who kept the Bonaparte name alive, proving once again that history really does love a twist.

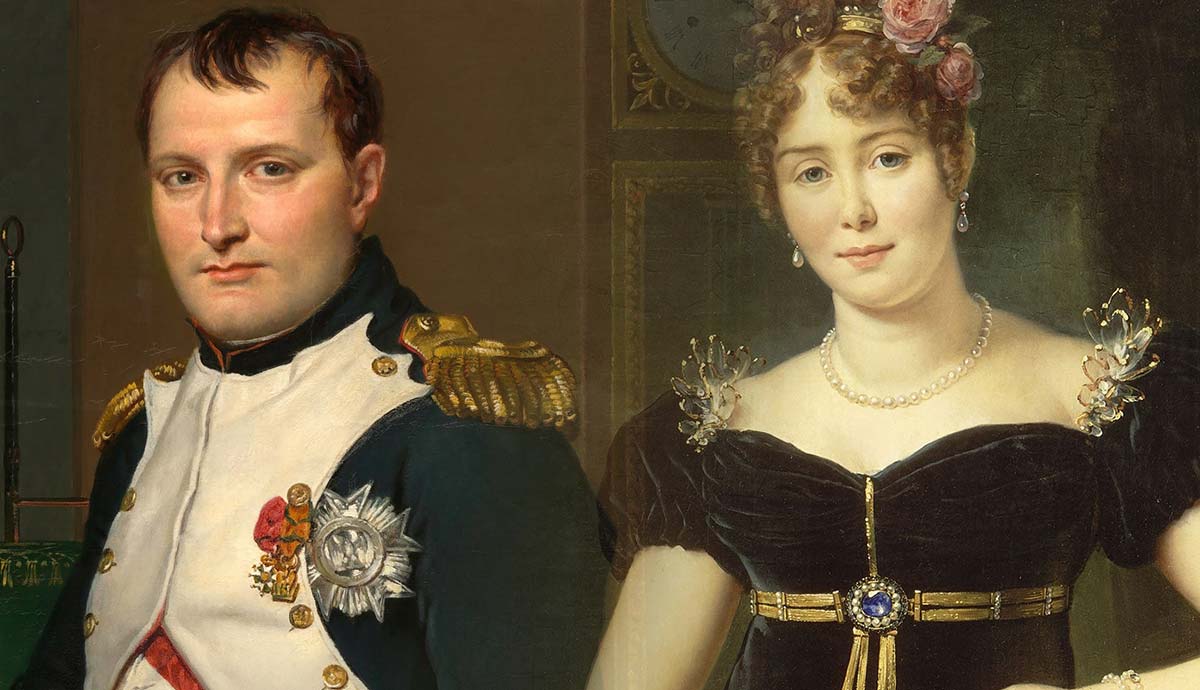

Josephine After Napoleon

When Napoleon reflected on Josephine near the end of his life, he called her “the most alluring, most glamorous creature I have ever known.” Pretty high praise from the man who divorced her after 13 years of marriage to wed a barely legal Austrian princess (although girls as young as 15 were technically “legal” at this time). “Divorce has become a stern duty for me,” he wrote, casting her aside not because he no longer loved her but because Josephine couldn’t give him an heir. Josephine’s inability to bear more children left her on the losing side of their personal battlefield.

Yet, in the end, Josephine may have had the last laugh. It was Josephine’s bloodline that carried the Bonaparte name forward. Her son, Eugène, and daughter, Hortense, whom Napoleon always treated as his own, remained integral to the family’s future. In fact, Hortense’s son, Napoleon III, would go on to become the first President of France after the Bourbon Dynasty fell, and then Emperor of France, ensuring that the Bonapartes maintained the royal status Napoleon fought so hard to attain.

All this rising and falling in status was thanks, in no small part, to Josephine. Without her, and the offspring she did have, the family might have faded into history after Napoleon’s downfall.

After their divorce, Josephine continued to live in style at her beloved estate, Malmaison, just outside of Paris. Napoleon, busy with his conquests, was eventually exiled to Elba in 1814 after his first abdication. During this time, Josephine remained active in the most vaunted social circles, hosting important dignitaries, including Tsar Alexander I. Rumors swirled that Hortense, staying with her mother and newly freed from her loveless marriage, was involved in an intimate liaison with the striking tsar.

Josephine was ever the gracious hostess, and it was during one of these Russian visits that she caught a chill. The illness worsened, and on May 29, 1814, Josephine passed away at Malmaison, her legacy sealed just a few weeks after Napoleon’s fall from power. The official cause of death was pneumonia.

After Josephine’s funeral, her children banded together to honor her memory, commissioning a magnificent white marble tomb at the church of Saint-Pierre-et-Saint-Paul in Rueil-Malmaison. Though it took over a decade to complete, the tomb’s beauty reflects the elegance and grace Josephine brought to both her role as empress and her life after Napoleon. Like her, the statue over her final resting place is beautiful but built of the kind of stuff that will make it endure the long years, whether they be good or less than so for France.

Napoleon penned wistfully from his exile, “A son by Josephine would have completed my happiness.” However, when he returned from his first island banishment, resplendent in victory once again, it was only to find Josephine had moved from this world to the next without him.