The Chremonidean War, c. 267-261 BCE, was a turning point in Greek history. The conflict saw the Athenians and the Spartans ally with Ptolemaic Egypt to free Greece from the influence of Antigonus II Gonatas of Macedonia. In a Hellenistic world dominated by monarchies with growing empires, it was the last time the great independent city-states, the polis (poleis), were the protagonists in world events. Despite its importance, the Chremonidean War is little known. A lack of sources makes much of the 3rd century BCE obscure, leaving us with only extremely brief summaries and scattered archaeology to piece together.

Macedonia & Greece

The details of the Chremonidean War are lost to us, but its context is easily understood despite the obscurity of the period. Since Philip II of Macedon’s victory over the Athenians and Thebans at the Battle of Chaironeia in 338 BCE, Macedonia had been the dominant power in Greece. Several times, various Greek states had led rebellions against Macedonia, but while each revolt claimed to be on behalf of Greek freedom, they were always the actions of individual states and a small number of allies. The Thebans rose up alone in 335 BCE and were swiftly crushed. That example discouraged others from joining Sparta’s revolt in 331 BCE, which failed. A decade later, the Athenians and Aitolians led a Greek coalition in the unsuccessful Lamian War.

Unable to defeat the Macedonians, Greece became entangled in the Wars of the Successors, which split Alexander the Great’s empire. Macedonia itself suffered through these wars just as much as Greece, but at the end of the 280s BCE, a new dynasty established itself. Antigonus Gonatas, son of the warlord Demetrius Poliorcetes, had led a tumultuous life trying to hold on to the remnants of his father and grandfather’s Antigonid Empire. A power vacuum in Macedonia in 280/79 BCE brought him to the throne, though it was some years until he was secure. His 40-year reign stabilized Macedonia and ensured its role as one of the great powers of its day. For Greece, Antigonus’s rise was further bad news as his long reign left behind a legacy of garrisons and tyrants that oppressed several Greek states.

Hellenistic Athens & Sparta

By the 3rd century BCE, the glory days of Athens and Sparta were a distant memory. The Spartans’ time as the most significant Greek military power ended when they were defeated by the Thebans at Leuktra in 371 BCE. That they recovered enough to rebel against Macedonia in 331/0BCE under King Agis III was impressive, even if Alexander disparagingly referred to the Spartan effort as a “war of mice.” Indeed, Sparta’s relative insignificance was often what saved it from destruction or total defeat as great powers invaded but became distracted and left to hunt bigger quarry.

After Agis’ defeat, it took half a century for Sparta to recover. However, by 281 BCE, signs of a renewed attempt to re-enter international politics were evident. A key figure in this process was King Areus I (c. 309-265 BCE). The Spartans had long had a peculiar dual monarchy with two kings reigning together. Areus marks the rise of a single, powerful ruler in Sparta who overshadowed their co-king and projected an international image similar to that of other Hellenistic kings (O’Neill, 2008, p. 68). Issuing Sparta’s first silver coinage, bearing his name and image, and an expedition to Delphi in 281 BCE, were meant to demonstrate a reinvigorated Sparta under a king of equal standing with his Hellenistic peers.

The Athenians had also lived through difficult times in the early Hellenistic era. In contrast to Sparta, Athens was a valuable target. Its wealth and size, and especially its large port at Piraeus, made it an important prize for any passing great power. The half century since defeat in the Lamian War had seen several regimes rise and fall. When possible, the Athenians attempted to reestablish their democracy, but they were often forced to endure periods of oligarchy and tyranny backed by a Hellenistic dynasty. But the Athenians stubbornly refused to give up on the idea of democracy and autonomy (Worthington, 2021, p. 22). In 286 BCE, the Athenians expelled the Antigonid garrison on the Museum hill opposite the Acropolis. Democracy was restored, but crucially, the Antigonids continued to hold the port of Piraeus and perhaps other sites in the Athenian territory of Attica.

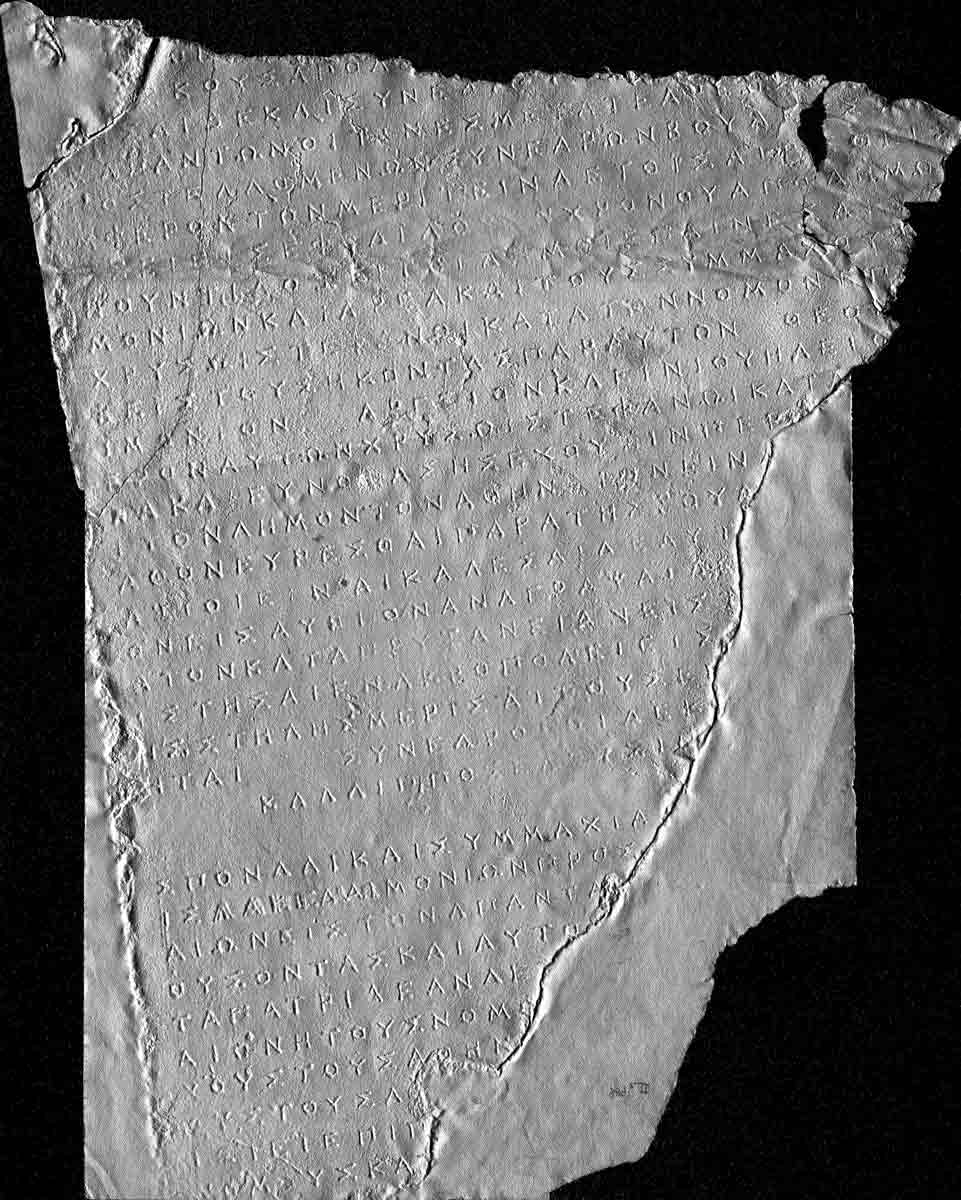

The Chremonidean Decree

The conflict of the 260s BCE owes its name to a decree passed by the Athenian assembly in 269/8 BCE by Chremonides of Aithalidai. The decree proposing an alliance between Athens and Sparta has survived through an inscribed copy discovered on the Athenian Acropolis and is one of the war’s few primary sources.

Though he has given his name to the war, we know little about Chremonides. He may, as did Antigonus Gonatas, have studied under Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism, while his brother, Glaucon, was an Olympic victor (Worthington, 2021, p. 117). His rise probably represents the generation of Athenian politicians who led the re-established democracy of the 280s and wished to fully liberate Attica.

The decree is an alliance between Athens and Sparta, which calls for the two cities to unite and free Greece as they did in the Persian Wars in 480-479 BCE. We can see the war aims of each side in the decree. The Athenians want Spartan help in liberating their territory. The Spartans, listed alongside their Peloponnesian and Cretan allies, gain the prestige of once again leading Greece. Interestingly, Areus is mentioned by name numerous times, showing that he now far outshone his fellow Spartan king and had become one of the most prominent figures in Greece. Success in the war would only further enhance Areus’ personal power and prestige.

The real central figure of the coming war also features in the decree. King Ptolemy II of Egypt is often regarded as the guiding force behind the alliance. The Ptolemies likely supplied money to the Spartans and assisted the Athenians with the liberation of Athens in 286 BCE, and with food supplies in the difficult years of the 280s (Worthington, 2021, p. 104).

This new alliance aligned all three parties in one project. The Antigonids and Ptolemies had long been rivals with their spheres of influence colliding in the Aegean. The trigger for the war could well be a clash between the Antigonids and Ptolemies in the region in 270 BCE (Waterfield, 2021, p. 160). The Greek allies were then the Ptolemaic instrument to strike Antigonus. In this sense, the war was a Ptolemaic rather than a Greek initiative (Waterfield, 2021, pp. 160, Worthington, 2021, p. 118).

The war that followed Chremonides’ decree was an alliance of the Athenians, Spartans, and Ptolemies against Antigonus. The Athenians hoped to liberate Attica. For Sparta, and perhaps more importantly for Areus, this was an attempt to lead Greece once more. Behind it all was the great power conflict between the Ptolemies and Antigonids.

Areus’ War

The war began in 268/7 BCE, soon after the alliance in the Chremonides’ decree was concluded. One of our brief narrative accounts, Pausanias (3.6), mentions that Antigonus attacked Athens with an army and fleet, making the next six years of conflict a protracted siege of Athens. Aid was sent from Egypt in the form of the Ptolemaic commander Patroclus, but he arrived with only a small naval force, and his marines could not challenge Antigonus’ army. This left Areus and the Spartans as the alliance’s primary force.

Though Sparta was allied with only a few Peloponnesian states, and others were certainly Antigonid allies, we do not hear of any fighting in the Peloponnese for most of the war. Areus’ task was to link up with the Athenians and Patroclus in Attica to confront Antigonus. This meant getting past the strong Antigonid garrison in the formidable fortress of Acrocorinth, which controlled the isthmus connecting the Peloponnese to mainland Greece.

It is believed Areus made three attempts to reach Athens in 267, 266, and 265 BCE (Worthington, 2021, p. 120). On one occasion, Areus broke through but turned back when he ran out of supplies and decided it was not worth running the risk just for the sake of his allies (Pausanias 3.6.6). A Hellenistic fortification wall constructed between Athens and Eleusis (20 km west of Athens) has been linked to Antigonus’ attempts to stall Areus’ advance (O’Neill, 2008, p. 77). As our main account of the war focuses on this episode, this may have been the critical point where the allies came closest to victory.

In either 265 or 264 BCE, Areus tried again. However, the Spartan army was defeated near Corinth, and Areus himself died in the battle. The defeat highlighted the fragility of Spartan recovery. Despite being a large polis, its unique social system made it difficult to create new citizens even as its citizen population fell due to wars and inequality. The Spartans were only ever one battle away from total defeat. The events of 265/4 may well have underlined the need for reform, which would lead to revolution in Sparta later in the 3rd century (Cartledge & Spawforth, 2002, p. 33).

Siege of Athens

With Areus and the Spartans now out of the war, the Athenians were left to fight on with only limited aid coming from the Ptolemies. The war in Attica probably took the form of a protracted siege and constant small-scale battles for fortified positions to control the countryside. With the Antigonids holding Piraeus, getting enough food into Athens had been a problem since the 280s. With Antigonus’ siege and Areus’ defeat, the situation only deteriorated.

Archaeologists have uncovered evidence that Patroclus established several camps and fortified positions along the coast of Attica, including at Koroni (Porto Rafti) in the east and at Sounion in the south. This must have aided in supplying Athens and allowed access to the countryside for food production. However, there was a tradition that Ptolemaic aid was of little help. Pausanias (1.7.3) later stated that the Ptolemaic fleet “did very little to save Athens.” This has been disputed, and the Athenians held out for several years, something they could not have managed on their own. Still, it is clear the Ptolemies never committed substantial resources to the war. They may have been hindered by the presence of an Antigonid fleet, but mainland Greece was always the outer limit of the Ptolemaic sphere of influence and never a central concern. For the Athenians, the war was a matter of life and death; for their Ptolemaic allies, it was a useful move to keep Antigonus busy, but nothing more.

Unable or unwilling to provide more substantial aid to Athens, the Ptolemies activated their diplomatic networks as the noose tightened. In 263 BCE, Alexander of Epirus, a Ptolemaic ally, invaded Macedonia, forcing Antigonus to call a truce and return north. The hungry Athenians took the opportunity to plant crops, but by the time of the harvest in 262 BCE, Alexander had been defeated, and Antigonus was back in Attica. With their last hope now extinguished, the Athenians had no choice but to surrender.

Kos and the End of the War

Surrender meant that Antigonid forces returned to the center of Athens and again occupied the Museum hill. Democracy was not formally abolished, but was certainly overseen by the Antigonids. The war to liberate Athenian territory ended with Athens more firmly under the Antigonid thumb.

The surrender in 262 BCE marked a severe decline for Athens. The pressure was eased slightly in the 250s with the withdrawal of the Museum garrison, but Piraeus was not liberated for another 30 years. The city ceased producing silver coinage and was forced to adopt the Antigonid policy. While Chremonides and his brother Glaukon fled to the Ptolemaic court in Alexandria, another prominent Athenian, the local history writer Philochorus, was executed. The loss of this cultural figure, combined with the 261 BCE death of Zeno of Citium, underscored the sense of the end of an era in Athens, while Zeno’s death brought an opportunity for Antigonus, a long-time follower, to make his presence felt (Worthington, 2021, p. 124).

The war ended in a crushing defeat for the Athenians and Spartans, but due to the limitations of our sources, the outcome for the Ptolemies is disputed. A much later source makes a passing reference to a victory of Antigonus over a Ptolemaic fleet off the Aegean island of Kos. The date of the battle is unknown, with some placing it at the end of the Chremonidean War, while others prefer a date a few years later, in the 250s. The later date seems likely given the battle’s absence from our brief accounts and other indications that Antigonus’ influence spread to the central Aegean in the mid-250s. Whatever the date, the victory at Kos reinforced Antigonus’ hold on Greece.

Despite our limited knowledge of events, it is clear that the war was critical to both the victors and the defeated. Antigonus and his successors would be challenged again in Greece, but not by the Athenians or Spartans. The Chremonidean War had shown that the resources of the two great poleis were not enough. Their time had clearly passed on the international stage. It was time now for the federal states, principally Achaia and Aitolia, to pool the resources of several poleis and take the lead against Macedonia.

Select Bibliography

Cartledge, P. and Spawforth, A. (2002) Hellenistic and Roman Sparta: A Tale of Two Cities, Routledge: London.

Kralli, I. (2017) The Hellenistic Peloponnese: Interstate Relations: A Narrative and Analytic History, 371-146 BC, The Classical Press of Wales.

O’Neill, J.L. (2008) “A Re-examination of the Chremonidean War” in McKechnie, P. and Guillaume, P., Ptolemy Philadelphus and His World, pp. 65-90, Brill: Leiden.

Waterfield, R. (2021) The Making of a King: Antigonus Gonatas of Macedon and the Greeks, The University of Chicago Press: Chicago.

Worthington, I. (2021) Athens after Empire: A History from Alexander the Great to the Emperor Hadrian, Oxford University Press.