In December 1914, the Allies and Germans on the Western Front in Europe were fighting a brutal war from the cold and muddy trenches of Belgium and France. Somehow, on Christmas Eve, a temporary truce broke out between the opposing forces. While it did not last long, accounts of the incident revealed a shared humanity and a symbolism of peace in the truce. Heavy fighting soon resumed, yet the memories of that day remained. Read on to discover more about the Christmas Truce of 1914.

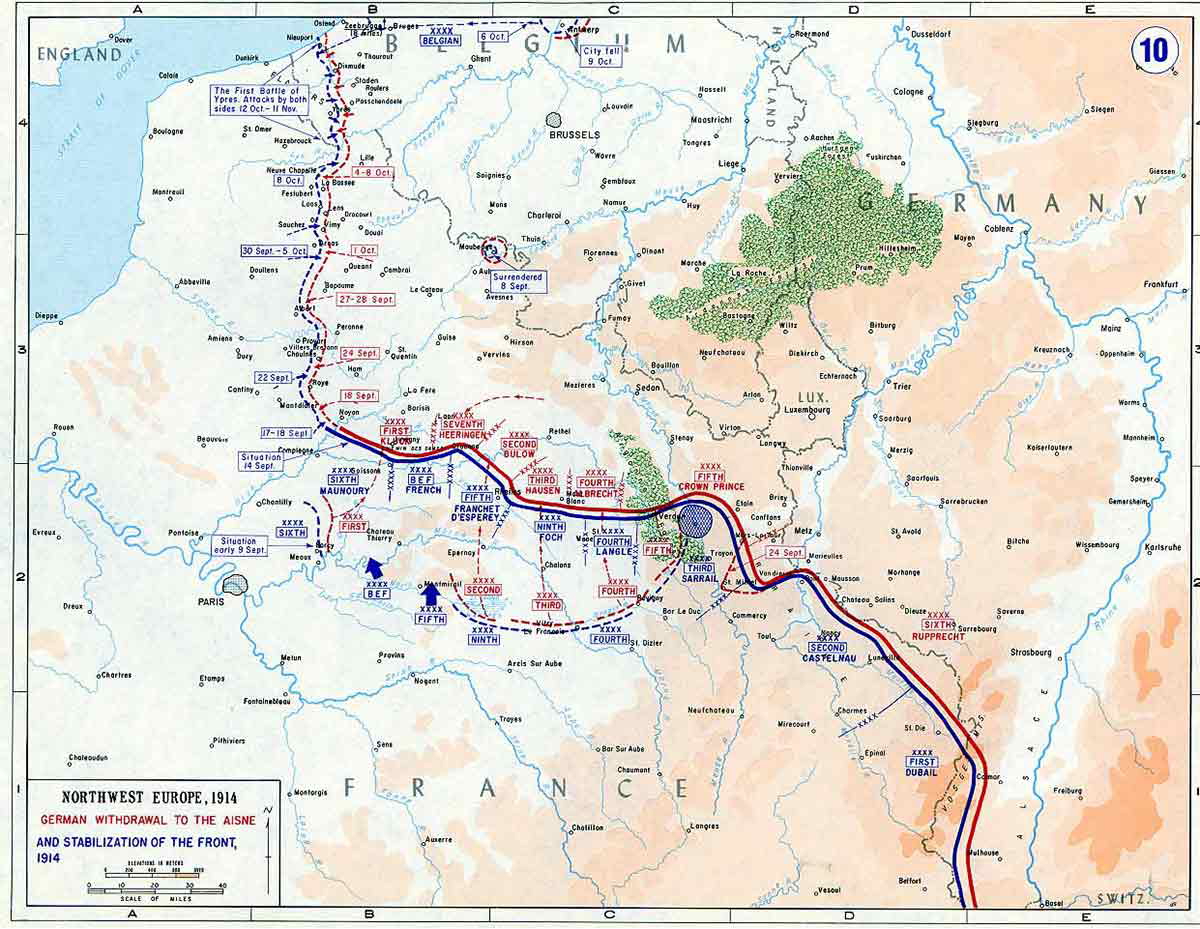

The Western Front in 1914

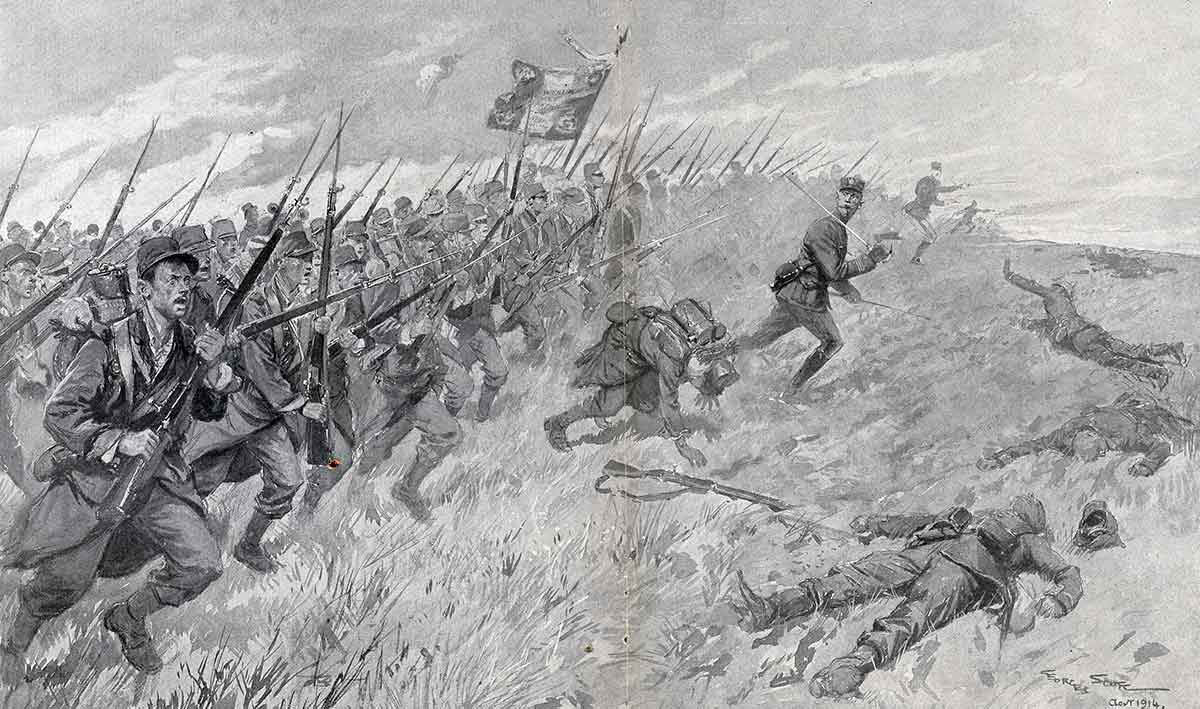

When open hostilities began in August 1914, a month after the start of World War I in Europe, both sides confidently believed that the war would be over by Christmas. The Germans launched an early offensive into Belgium, Luxembourg, and France, hoping to quickly knock the French out of the conflict.

As German forces approached Paris, the British and French initiated a counteroffensive that halted the German advance but did not force a retreat. With occasional movement of a few miles on either side, the line running from the Belgian coast to the Swiss border became the Western Front battleground for the duration of the war.

As the conflict bogged down into static warfare, the Allies and Central Powers dug a series of trenches from the English Channel to the Swiss Alps, roughly 475 miles long. The trenches stabilized the front but also created a no-man’s-land between them. Armies launched waves of attacks across the no-man’s-land towards enemy trenches that were repulsed with heavy casualties on both sides. When one trench fell, a new defensive one was quickly built nearby, keeping the line intact.

By the end of 1914, both sides were bloodied and exhausted. The French had suffered 950,000 casualties, while the Germans lost 800,000 to trench warfare. The realization that the war could drag on for years became clear. Millions of soldiers were stuck fighting in the trenches as Christmas approached.

Life in the trenches was miserable. While there were many moments of stress and fear during battle, the biggest challenge was often boredom. Many waking hours were spent waiting to be called to climb up the trenches to attack or waiting for the enemy to strike. Even worse was the threat of infection and disease due to pests, dampness, and lack of proper hygiene.

The 1914 Christmas Truce

The first signs of a truce came shortly before Christmas. Despite continued fighting, some of the trenches, the Germans in particular, decorated their spaces with Christmas trees and candles.

On Christmas Eve, soldiers on both sides started singing Christmas songs. In one case, the Germans sang Stille Nacht (Silent Night). The British responded with The First Noel. Then, there were shouts from both sides of Merry Christmas.

The first moments of the impromptu ceasefire seemed to occur between British and German forces. People lit lanterns, and friendly words were exchanged despite the language barriers.

On the following day, Christmas, the Western Front was quiet enough that some men began to venture out of their trenches. The sworn enemies met in no-man’s-land. One of the first acts of mutual kindness was that each side was allowed to retrieve their dead for burial.

Then, as soldiers wished each other a Merry Christmas, gifts, such as food, drink, and tobacco, were exchanged. Combatants showed each other photographs of their loved ones and talked about their longing for home. Friendly games of football reportedly occurred along the Western Front.

The Christmas Truce became a spontaneous event from the ground up, and it was never sanctioned by the higher-ranking officers. Many feared they might lose control of the soldiers under their command. The open friendliness between enemies was also considered dangerous for keeping up the motivation to fight. This was especially the case in the few instances where the truce lasted for days, well past Christmas.

As unusual as this event was, informal truces were not unique to World War I. Similar spontaneous episodes had occurred in other prolonged wars in history. However, what made this different was how widespread the ceasefire was.

The German Perspective

In 2003, German historian Michael Jurgs published a book on the Christmas Truce titled, in the English translation, The Small Peace in the Big War. In the book, Jurgs asserted that one of the reasons why the event took place was because many Germans stationed at the front had worked in England before the war. Indeed, it seems that many truce talks along the trench lines were initiated by Germans speaking fluent English.

Another revelation confirmed that soccer matches did break out across the lines during the ceasefire. However, there weren’t many balls available, so soldiers improvised by tying straw together with string or using empty jam boxes as a football.

Among the primary sources Jurgs cited in his book were diary entries by a German lieutenant named Kurt Zehmisch. Zehmisch was a schoolteacher who spoke both English and French. In one of his entries, Zehmisch recalls that on Christmas Eve, one German soldier called out to the British in English. Following that, a lively conversation developed between both camps.

Another German infantryman described soldiers of both sides climbing out of their trenches and over the barbed wire and meeting in no-man’s land. That is where a British soldier had set up a makeshift barber’s shop. The English barber charged a couple of cigarettes per haircut and was indifferent as to whether the customers were British or German.

Some Germans refused to participate in the temporary truce. Casualties were high, and wounds were deep, causing many soldiers to resent offers of peace. One lieutenant lamented that the enemy wanted to see the political disappearance and social eclipse of Germany. His response to this: “But all the same, you are Englishmen whose annihilate (sic) we consider as our most sacred duty.”

The British Perspective

The British soldiers were just as surprised at the truce as the Germans. Most of the British Expeditionary Forces were facing German armies based in northern France and Belgium. The fighting between them was a battle for dominance over Europe by two great powers.

British private Marmaduke Walkinton recalled the proximity of the enemy lines, allowing for better communication. “We were 300 yards from the Germans…Anyway, eventually a German said, ‘Tomorrow you no shoot, we no shoot.’” Indeed, neither side brought guns when they met.

While meeting in no-man’s land, English troops shared some of their Christmas packages sent from the home front. They were metal boxes filled with chocolates, sweets, cigarettes, and tobacco. Included in the boxes were greetings from King George V and Queen Mary.

Miraculously, in many sections of the line not a shot was fired over Christmas. English Regimental Sergeant Major George Beck wrote in his diary, “Not one shot was fired. English and German soldiers intermingled and exchanged souvenirs. Germans were very eager to exchange almost anything for our bully beef and jam.”

Senior officers and the British high command were surprised by this close fraternization over Christmas. During the war, communication with the enemy was strictly forbidden, and soldiers making contact could be considered traitors and then charged with treason.

Still, this was a chance to very briefly rest and relax, if only for a few hours. British troops on the front lines were not as fortunate as those staying behind the lines, who were able to enjoy some quiet and full Christmas dinners.

The French Experience

While the British and Germans were rivals for global power, the French felt a more personal animosity toward Germany. In 1870, France was soundly defeated in the Franco-Prussian War. Aside from societal humiliation, France had also lost the province of the Alsace-Lorraine region to the newly established German Empire, whose establishment was pointedly announced in the Palace of Versailles.

By December 1914, most of the fighting on the Western Front had taken place on French soil. Vast swaths of land lay wasted from artillery barrage and dug trenches. France viewed the German forces as archrivals who were to be defeated at any cost. This perception made the Christmas Truce even more remarkable.

Louis Barthas became a corporal during the war and was involved in the heavy fighting. He also left a written account of the Christmas Truce, recording his thoughts about this remarkable event: “Shared suffering brings hearts together, dissolves hatred and prompts sympathy among indifferent people and even enemies. Those who deny this understand nothing of human psychology. French and German soldiers looked at one another and saw that they were all equal as men.”

In his book Silent Night: The Story of the World War I Christmas Truce, published in 2001, historian Stanley Weintraub stated that the French and Belgians generally reacted more harshly to the truce than the British. However, many also saw it as a welcome opportunity to halt the fighting for the holiday.

On the other hand, horrified by the Christmas Truce, the French high command reacted negatively like their British and German counterparts, and many French units did not participate in the ceasefire. While some British newspapers reported on the Christmas Truce, French newspapers mainly did not write about it.

The Belgian Experience During the Christmas Truce

Belgium faced its own unique situation in December 1914. Almost all of the country was overrun by the German army during the first month of fighting. Only a small parcel of land in the northwest around Ypres, in West Flanders, remained independent. Belgium had not been occupied since achieving independence from the Netherlands in 1830.

The Battle of the Yser solidified the line for the Belgians in October 1914 when the German advance was stopped. Only 52,000 Belgian troops remained to hold on to their remaining territory. Many soldiers were already captured or had fled the country.

Yet even in this desperate situation, Belgian troops dropped their arms on Christmas to mingle with their German opponents. They met in an area named Hoge Brug.

A Belgian chaplain named Jozef van Ryckeghem recorded the event in his memoirs. He first noticed the lack of gunfire. Then, there were voices singing Christmas Carols from the German side. The Belgians applauded, then replied with their own singing. Finally, both sides left their fortified trenches to meet. “There is fraternalism and cigars, chocolates and all kinds of trinkets are exchanged,” wrote Ryckeghem.

In another area of the Belgian line, a German officer found a piece of religious Belgian ecclesiastical art, a golden monstrance, in a convent nearby. The German officer then arranged for the item to be given to a Belgian army chaplain.

Like the other military high officials from the countries involved in the conflict, Belgian commanders frowned upon fraternization with the Germans. They particularly despised friendliness with an enemy that had only recently conquered and occupied most of their country.

What made the Christmas Truce of 1914 unique was that contact spontaneously took place in several isolated locations along the lines. What made this even more remarkable was that the widespread halt to fighting in December 1914 never occurred again for the duration of the war. The Christmas Truce was a testament to the futility of war. Brave and exhausted soldiers from both sides summoned the energy and courage to stop shooting, shake hands, and talk for a brief period in the eye of the storm.