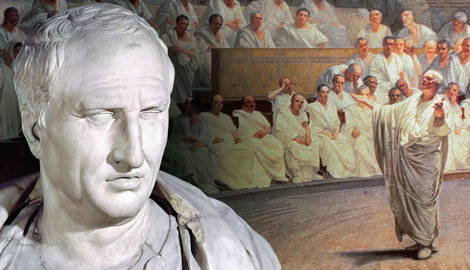

A novus homo, no one expected Marcus Tullius Cicero to reach not only the rank of consul, but be hailed princeps senatus, in the dying years of the Roman Republic. He championed Rome’s republican traditions while strongmen such as Pompey Magnus and Julius Caesar were dismantling them. His opposition to Mark Antony’s autocracy following Caesar’s death would see him martyred as one of the last defenders of the Republic. But Cicero had the last laugh. A prolific and elegant writer, his philosophical treaties, his published speeches, and his personal letters have largely shaped modern perceptions of 1st century BCE Rome, including our perception of Mark Antony as ambitious and dangerous.

Early Life – De Inventione (106-80 BCE)

Marcus Tullius Cicero was born in the town of Arpinum, about 100 kilometers outside Rome, on January 3rd, 106 BCE. He came from a wealthy equestrian family of Roman citizens, but he was not a member of one of the aristocratic families that dominated politics in Rome. In fact, the first man of Arpinum to make a major impact on Roman politics was the general and seven-time consul Gaius Marius, who first held the consulship the year before Cicero’s birth, in 107 BCE.

Cicero’s father, also Marcus Tullius, seems to have refrained from entering Roman politics due to general poor health and a weak disposition. He instead devoted himself to academic pursuits, which encouraged his two sons with his wife Helvia, Marcus and Quintus, to do the same. But the boys also had political ambitions, potentially fueled by Marius’ meteoric rise to power during their youth.

It is unclear exactly when Cicero made his way to Rome, but in 90 BCE, the 15-year-old is recorded serving in the Roman military under Sulla in the Social War. It was normal for young aristocrats to gain military experience in their teenage years as a prelude to passing through Rome’s cursus honorum of public offices. He then established himself in Rome and studied at the feet of Greek academics and philosophers there, as well as with the famous Roman lawman Quintus Mucius Scaevola. There he met fellow student Titus Pomponius, whom he affectionately called Atticus and would become his best friend and second brother.

Cicero soon started his career in the law courts reformed by Sulla between 82-80 BCE. In 81 BCE, he defended Publius Quinctius and published the speech Pro Quinctio that he made defending him in a business case. The following year, he also published his defense speech Pro Roscio Amerino, from a high-profile case of a Roman citizen accused of murdering his father. Many of Cicero’s speeches survive due to Cicero himself publishing them.

By 80 BCE, Cicero was planning to head to Greece to continue his studies, but before leaving, he married Terentia. She was probably from the family of Terentii Varrones, a noble plebeian house. In fact, Terentia’s niece was made a Vestal Virgin, which was a highly prestigious position and a sign of her family’s nobility. This would have suited Cicero, as she came with a large dowry and plenty of social connections. In 79 BCE, she gave birth to their daughter Tulia, who was the apple of her father’s eye throughout his life. Terentia may have been unimpressed when, in the same year, Cicero headed to Greece to work on his skills as an orator, including training his body and lungs for the trials of public speaking. He stayed there until 77 BCE.

During the early years of his life, Cicero wrote his De Inventione, which was published in 84 BCE and is his earliest known work. Reflecting his studies of oration and law at the time, it explains the five canons of rhetoric and public speaking: invention, arrangement, style, memory, and delivery.

Early Political Career – In Verrem (81-63 BCE)

When Cicero returned from Greece, he was ready to pursue the cursus honorum in earnest. In 75 BCE, he was elected to the position of quaestor at the age of 30, the minimum age required to be eligible for the position. In that capacity, he was sent to Sicily to provide administrative and financial assistance to the governor. He reportedly performed well, and his fairness made him popular among the locals, building Cicero’s clientele. Roman society relied on a patron-client system that tied superiors and inferiors together through bonds of mutual obligation. Politicians needed large client bases to ensure their election.

Only a few years later, in 70 BCE, Cicero would be called on by his Sicilian clients to prosecute Gaius Verres, who served as governor of Sicily in 73 BCE, on their behalf. Sicily was a wealthy and extremely important province as it was responsible for much of Rome’s grain supply at the time. Verres reportedly used his position to despoil temples and extort the locals. Cicero published a series of speeches known as In Verrem, in which he annihilated Verres’ character and vehemently denounced his actions.

Verres hired the most prestigious lawyer in Rome, Quintus Hortensius Hortalus, to defend him. Going toe-to-toe with the famed rhetorician may have been one of Cicero’s motives in pursuing the case. However, Cicero’s first speech was so effective that Hortensius advised Verres to plead no contest and go into voluntary exile, where he spent the rest of his life. Cicero seems to have been disappointed that he did not get to finish the trial properly, and published all his speeches despite only delivering one.

Cicero’s success in this case earned him the accolade of Rome’s greatest orator at the time, which opened the path for him to be elected aedile in 69 BCE at the minimum age of 36, and praetor in 66 BCE, at the minimum age of 39. Cicero and Terentia had their son, Marcus, in 65 BCE.

Consulship – In Catilinam (63 BCE)

In 63 BCE, Cicero was successfully elected consul, the culmination of most Roman political careers. This was a feat since Cicero was a novus homo, or “new man,” whose family had not previously held the consulship. These were few and far between in the aristocratic world of the late Roman Republic. But despite his prestigious career and his support of traditional Senatorial rights, his status meant that he was never really accepted among Rome’s traditional “optimates.”

Cicero achieved several things during his consulship, which he shared with Gaius Antonius Hybrida, a relative of Mark Antony. He successfully opposed a land bill proposed by a tribune of the plebs that would have established a group of commissioners with semi-permanent authority over land distribution. He was also active in the courts, for example, defending Gaius Rabirius for killing a tribune of the plebs, whose person was considered sacrosanct while in office. But everything else Cicero did as consul was overshadowed by the events of the Catilinarian Conspiracy, which we know about both from Cicero’s published orations and a monograph written by the contemporary Roman historian Sallust.

The conspiracy was led by Lucius Sergius Catiline, who was defeated in the consular elections in 63 BCE for the next year. Unhappy with the situation, Catiline gathered a group of discontents around him with the purpose of claiming power illegally. As consul, Cicero got word of the plot, with evidence coming in October 63 BCE from Marcus Licinius Crassus, who had letters describing plans to massacre prominent citizens. Cicero also received word that Catiline was gathering troops in Etruria. While Cicero could not definitively prove Catiline’s involvement, he took the evidence for the broader plot to the Senate, and they passed a senatus consultum ultimum giving the consuls permission to do whatever it took to resolve the situation, declaring martial law.

The conspirators met on November 6 and found two volunteers to kill Cicero. The attempt failed, and Cicero used this to convince the populace that the conspirators planned to destroy the city. The following day, the Senate met, and Cicero denounced the conspiracy, with Catiline himself responding. Cicero was convincing, and Catiline was forced to flee to Etruria. Hybrida was dispatched to deal with the forces gathering there, while Cicero identified conspirators still in Rome. On December 2 or 3, five men were arrested and confessed their guilt.

Although martial law had been declared, Cicero did not want to act alone and execute the prisoners, as the senatus consultum ultimum offered no immunity from subsequent prosecution for his actions. Cicero organized a debate in the Senate regarding what to do with the prisoners, since it was believed that traditional house arrest would not be enough to stop the violence they were embroiled in. Julius Caesar argued for lenient treatment, suggesting imprisonment in Italian towns. But it was Cato the Younger’s argument in favor of the death penalty that won the day. Cicero had the five conspirators executed without trial. Shortly after, Catiline’s army was defeated, and Catiline died in the battle.

Cicero was initially praised as a hero for saving the Republic from this threat and was even voted the title pater patriae, or father of his country. But Cicero seems to have overestimated his popularity and the support for his actions, exaggerating both the threat to Rome and his own role in subsequent accounts of events, including the four speeches he gave, In Catilinam, which he later published. But his enemies now had ammunition to use against him: he had executed Roman citizens without a trial.

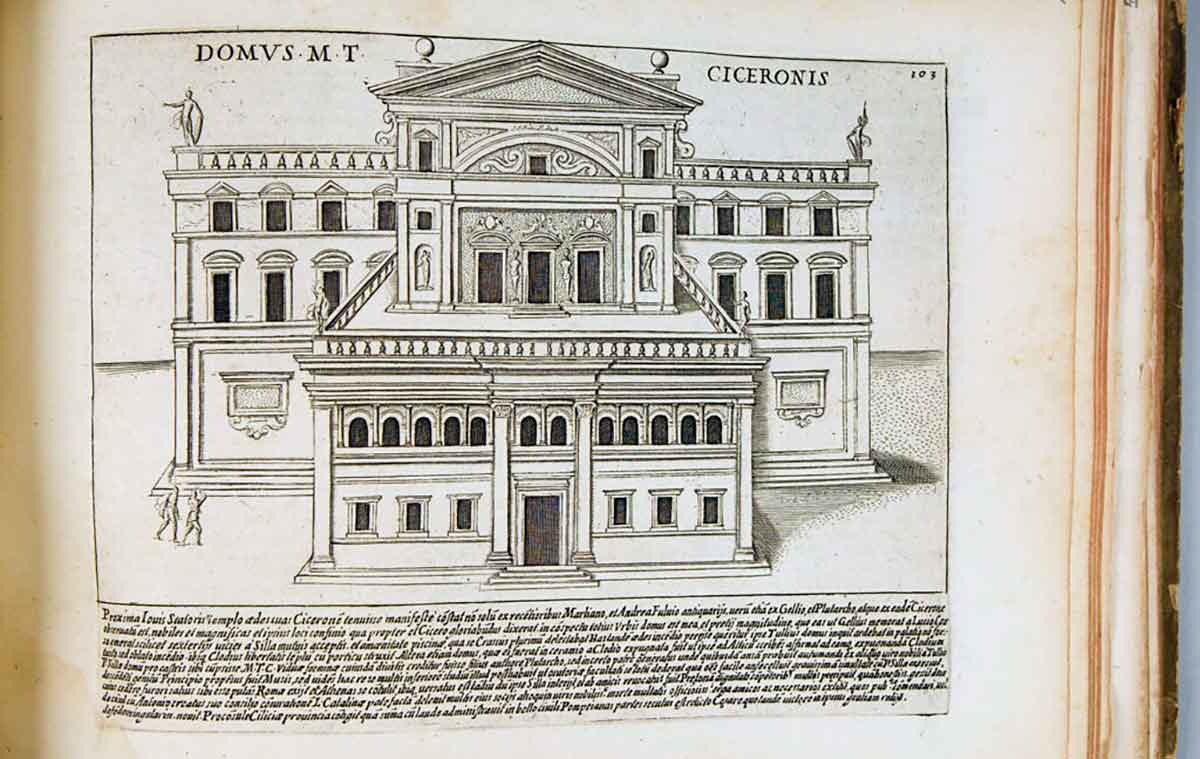

Nevertheless, before the end of his consulship, Cicero felt confident enough to buy a house from Crassus, the richest man in Rome, on the Palatine Hill, borrowing two million sesterces to close the deal.

Exile & Return – Epistulae (62-57 BCE)

Cicero remained popular and influential after his term in office, so much so that in 60 BCE, Caesar invited him to enter into an agreement with himself, Pompey, and Crassus to collaborate for their collective political benefit. Cicero refused, according to him, because he thought it undermined the principles of the Republic. Consequently, the First Triumvirate was formed without him, and he became a potential threat rather than an ally.

Caesar held the consulship in 59 BCE and passed many reforms that benefited the triumvirs. Not wanting these forms to be undone when he left office, the triumvirs had a patrician ally, Publius Clodius Pulcher, adopted into a plebeian family and elected tribune of the plebs in 58 BCE. Whether of his own initiative or with the support of the triumvirate, he passed a law that made it illegal to provide “fire or water” to anyone who had killed a Roman citizen without trial. This sentence of exile was clearly targeted at Cicero.

Cicero tried to claim exemption from this law, noting that he had the support of the Senate for all his actions. He grew out his hair, dressed in mourning, and toured the streets of Rome to gain support, but was constantly hounded by Clodius’ gangs. In the end, he begged Caesar for assistance, but while apparently sympathetic, Caesar declared the issue out of his hands.

Cicero was exiled and arrived in Thessalonica in May 57 BCE. His house in Rome was confiscated, part of it purchased by his neighbor, and part consecrated for a temple of Liberty to ensure that Cicero could never return to it.

While Cicero wrote letters throughout his life, especially to his brother Quintus and his friend “Atticus,” a great deal of his correspondence dates to this period. He shared that he had suicidal thoughts, though suicide was considered a noble end in certain circumstances in the Roman world.

But his exile was short-lived. The following year, another tribune of the plebs, acting on behalf of Pompey, who wanted Cicero indebted to him, raised a vote in the Senate for Cicero to be recalled. Only Clodius, who passed the original law, opposed the bill. Cicero returned, arriving at Brundisium in August 57 BCE to cheering crowds. He had the pontiffs invalidate the consecration of his land and started to rebuild.

Return to Politics – De Re Publica (57-50 BCE)

Cicero tried to reenter politics as an independent operator, but Rome was not the same as it was before. The triumvirate dominated politics, and Cicero was forced to cooperate with them or risk being excluded from Rome’s public life altogether. In 56 BCE, he praised Caesar’s achievements and asked the Senate to vote thanksgivings for his victories in Gaul. He also had money voted to pay Caesar’s troops and delivered a speech about the consular provinces that helped prevent Caesar from being stripped of his command in Gaul.

Dealing with the new reality of being relatively impotent in politics, Cicero focused on his writing. It was during this period that he produced his De Re Publica, a six-book treatise on the Roman constitution based on Plato’s Republic. The work includes the famous Scipio’s Dream, given to the Roman general Scipio Aemilianus, in which Cicero explores the nature of the divine.

Cicero also continued to be active in the law courts, defending his friends, but also allies of the triumvirate, many of whom he had previously denounced. This damaged his public reputation and standing. It inspired Catullus’ comments that Cicero was “the best defender of anybody,” suggesting he had no scruples when it came to who he chose to defend.

In 51 BCE, Cicero divorced his forceful wife Terentia, remarrying a much younger girl, Publilia, in 46 BCE. The same year as his divorce, Cicero accepted a promagisterial appointment in Cilicia. As in Sicily, he seems to have been moderate and conscientious in his administration, winning him local support, and he even saw military action.

When Prince Pacodus of Parthia crossed the Euphrates, started to ravage the Syrian countryside, and besieged the Roman commander Cassius, Cicero marched to Cassius’ aid with two understrength legions and a large contingent of auxiliaries. He used his cavalry to defeat Parthian horsemen. He also dealt with revolting tribes in the Cilician mountains, leading his troops to hail him imperator in recognition of his success. But as news of the civil war between Caesar and Pompey arrived, Cicero left the province in the hands of his brother Quintus and returned to Rome.

Civil War – De Natura Deorum (49-44 BCE)

When Cicero arrived in Rome in January 49 BCE, he stayed outside the pomerium, the ceremonial border of Rome, as passing it would mean giving up his proconsular imperium, which enabled him to command Roman troops outside of Rome. While he may have said he was awaiting an unlikely triumph for his actions in Cilicia, he was almost certainly waiting to see what would happen between Pompey and Caesar.

Caesar courted Cicero’s support. But despite Cicero and Caesar being on friendly terms—Caesar was one of the friends who sent Cicero a letter of condolence when his daughter Tulia died unexpectedly in 45 BCE—Cicero favored Pompey. Because Pompey was the one in Rome and Caesar was the one marching his troops into Italy, Pompey appeared like the defender of the Republic, when, in reality, both were looking to further their own ambitions.

When Caesar crossed the Rubicon into Italy with his army, Cicero fled Rome and joined Pompey’s camp. He traveled with Pompey’s forces to Pharsalus in Macedonia, but by the time of the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BCE, where Caesar defeated Pompey, forcing him to flee, Cicero was thoroughly disillusioned with the righteousness and competence of the side he had chosen. Following the defeat, Cicero refused to take charge of Pompey’s forces or continue the war.

Cicero returned to Rome, crossed the pomerium, and gave up his imperium. Forgiven by Caesar for choosing Pompey, Cicero tried to resume his political life, maintaining a public friendship with Caesar and using his influence to try and steer the now dictator towards moderate policies. It was due to this public friendship that the liberatores, led by Marcus Junius Brutus, did not approach Cicero to be part of the plot to assassinate Caesar on the Ides of March, 44 BCE.

Cicero would later write letters to Brutus stating that he wished he had trusted him to be part of the liberation, but whether he really felt that way before Caesar’s death is unclear. The fact that he did not participate in the assassination, which had a mixed reception, probably helped Cicero use his oratory skills to establish himself as a popular leader in the months of instability that followed. This allowed him to broker an agreement in the Senate between the Caesarians and the liberatores that granted amnesty to the assassins and maintained Caesar’s reforms as lawful. In April 43 BCE, this earned Cicero the title princeps senatus, or first among the senate.

Surprisingly, it was during these turbulent years that Cicero wrote many of his philosophical works. He translated many Greek philosophical concepts into works for Roman audiences and was so influential that he is considered to have created the Latin vocabulary for discussing Greek philosophy. Notable among his works published in 45 BCE was De Natura Deorum, a dialogue on the nature of the divine in which he explores Epicurean philosophy, Stoicism, and Academic Skepticism.

Death & Philippicae (44-43 BCE)

While Cicero and Caesar had always had mutual respect for one another, Cicero thoroughly disliked Mark Antony. Cicero characterized Antony as scheming and using Caesar’s murder for his own benefit. He also accused Antony, who was the executor of Caesar’s public will, of deliberately misinterpreting Caesar’s intentions for his own benefit.

When Octavian, later known as Augustus, emerged as Caesar’s adopted son and heir, Cicero supported the 18-year-old youth as the head of the Caesarian party in opposition to Antony. Cicero famously denounced Mark Antony in a series of speeches, later published, which he called the Philippicae. This was a reference to the speeches that the famous Athenian politician Demosthenes made to denounce Philip II of Macedon three centuries earlier. Cicero later supported the governor of Cisalpine Gaul in convincing the Senate to declare Antony an enemy of the state for his actions there.

While Cicero had chosen the losing side in civil conflict before, Antony was significantly less forgiving than Caesar. When Antony and Octavian came to terms, forming the second triumvirate along with Lepidus in November 43 BCE, they created a list of enemies to proscribe. While Octavian reportedly argued for sparing Cicero for two days, Antony wanted revenge for the vitriol of the Philippicae.

While he initially fled, Cicero was eventually caught on December 7, 43 BCE, despite his slaves lying on his behalf. He reportedly leaned his head out of his carriage to give his killers a good swing. As well as being beheaded, his hands were cut off, as Antony wanted the hands that wrote those speeches brought to Rome. Cicero’s head and hands were nailed to the Rostra in the Forum Romanum as had been done in times old, but he was the only victim of these proscriptions to be displayed in this way. Antony’s wife, Fulvia, reportedly stabbed his tongue with her hairpin as a final revenge against Cicero for his speeches.

While Cicero had an eventful life, he also had an eventful afterlife, with his extensive writings on politics and philosophy influencing readers for millennia. In fact, Ciceronian Latin is considered the standard for classical Latin, and there is not a student of the language who has not read one of Cicero’s speeches in its original glory.