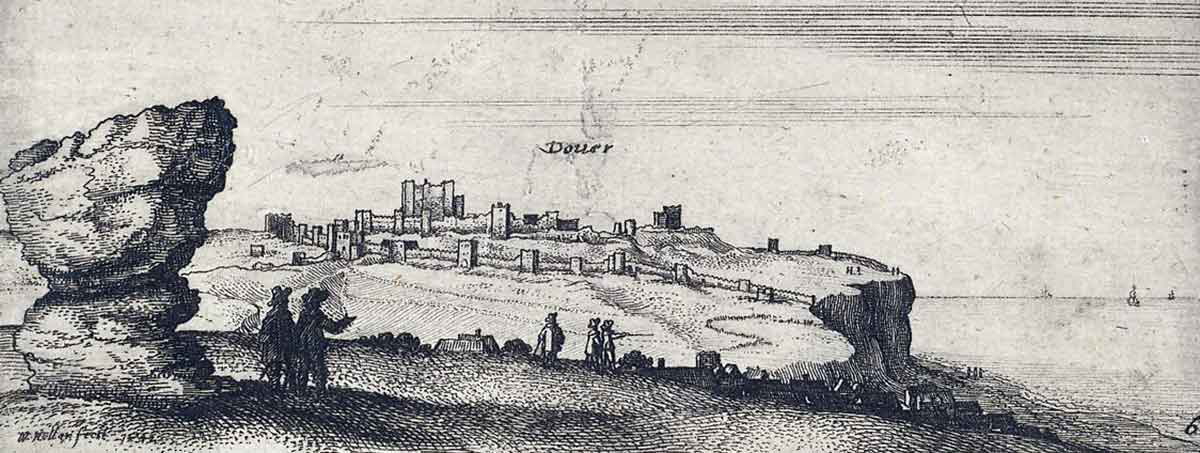

Throughout England’s long and turbulent history, the White Cliffs of Dover have become a symbol of the nation. The vertical white cliff face, facing continental Europe, has stood as a physical barrier and shield against invasion from abroad. Throughout the ages, the Cliffs of Dover and the surrounding area have played a pivotal role in defending the realm and helping steer the course of history.

What Are the White Cliffs of Dover?

The White Cliffs of Dover are located in the southeastern corner of Great Britain in the county of Kent. The minerals for the cliffs formed over 100 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous period. The minerals come from the fossilized remains of algae that have built up over the course of millions of years. Though it is primarily made up of the remnants of these microscopic organisms, the cliffs occasionally contain the fossilized remains of much larger creatures, such as sponges, anemones, and urchins. Changes in sea level and shifts in the tectonic plates eventually raised the geological formation above sea level. At their highest, the cliffs stand around 350 feet above sea level.

The stone itself is a white color due to erosion and has layers of grey flint streaked through it. This stratification matches the mineral layers across the channel at the Alabaster Coast of Normandy, France, making them part of the same geological formation. It is a soft stone and is subject to erosion at a rate of about eight inches to a foot per year. However, the formation is large enough that the Cliffs will continue to exist for tens of thousands of years at the current rate of erosion.

The cliffs are located at possibly the most strategically important location in the British Isles. They stretch along the coast for a length of about eight miles, flanking the port of Dover on the English Channel, the waterway that separates Britain from the rest of Europe. In fact, Dover is the closest point to continental Europe, only 20 miles away from the French port city of Calais, which is close enough to see on a clear day. Because of this location, the White Cliffs of Dover have been the most obvious place to launch an invasion of Britain, and the first line of defense for England.

The Cliffs of Dover in Roman Britain

Though there is some evidence of an Iron Age hill fort at Dover, the White Cliffs first entered written history in 55 BCE. In his Commentarii De Bello Gallico, or Commentaries on the Gallic War, Julius Caesar wrote about his first attempt to invade Britain. Taking two of his legions across the English Channel from Gaul, Caesar attempted to cross into the mysterious island at the narrowest point. Aided by the White Cliffs, the local Celtic inhabitants did everything in their power to prevent this from happening.

As the Roman ships approached, the Britons hurled weapons, stones, and anything else at hand down the sheer cliff face. Because of the height of the cliffs, the Romans were unable to retaliate. Seeing the aggression of the Britons, and the seemingly insurmountable advantage given by the white cliffs, Caesar stated that “it seemed to me that the place was altogether unsuitable for landing.” Still undeterred, he would lead his fleet to the north, landing on more hospitable terrain. Thus, the first historical record of the White Cliffs of Dover was as a barrier against outside invasions.

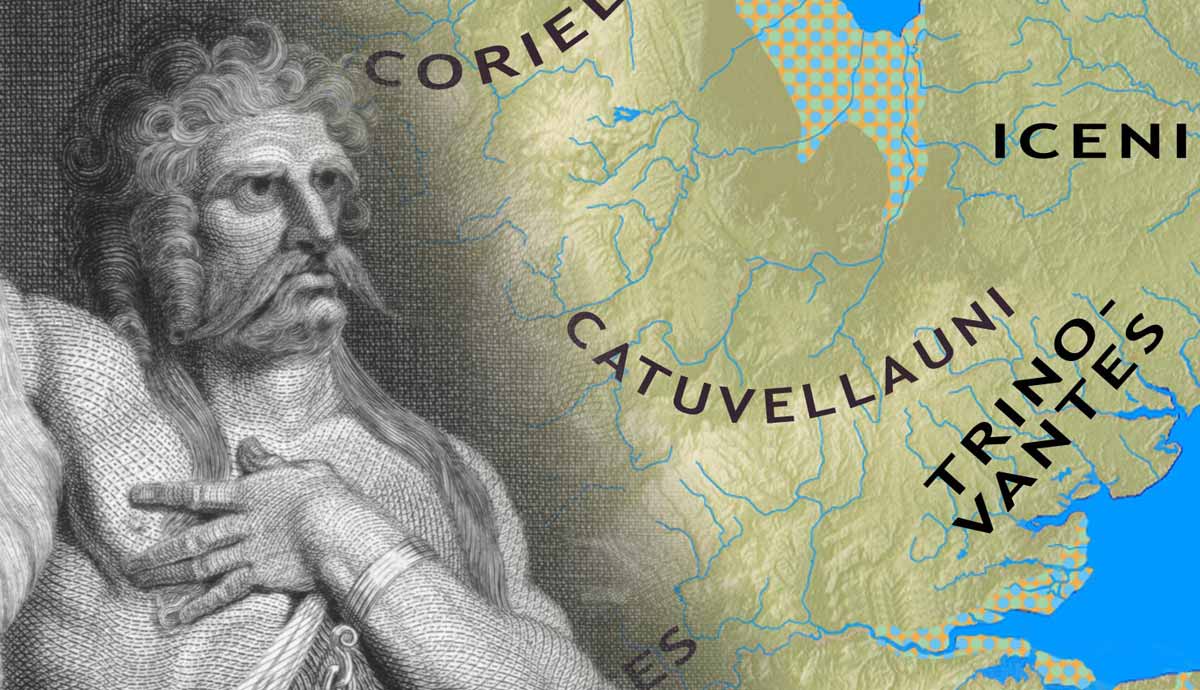

Caesar would launch another invasion but ultimately leave Britain without conquering the island. But the Romans did not forget the distant island. In 43 CE, the emperor Claudius, in need of a military victory to secure his power, decided to invade Britain and establish a permanent Roman presence in the region. Information about the initial landing place is sparse, though it does not seem to be Dover. After the Romans secured much of Britain, Dover was still seen as a vital location, not only for defense but also as a way to secure shipping in the Strait of Dover. To protect vessels in this often rough and storm-wracked waterway, the Romans would build a pair of lighthouses to guide sailors.

As the Roman Empire began to crumble, Britain was subject to seaborne raids by Germanic tribes who preyed on the vulnerable coast of the collapsing empire. In response to these repeated attacks, the Romans created what is known as the Saxon Shore, a series of defenses on the coast of southern Britain and northern Gaul, or modern-day France and Belgium. Dover was part of this defensive chain, with a garrison placed to prevent incursions from the raiders. In 410, the Roman legions pulled out of Britain, leaving the inhabitants to “look to their own defenses.” Information during this era is scarce, but the Saxon Shore eventually crumbled, and Britain was invaded by the Angles, Saxons, Frisians, and other Germanic tribes that pushed the Romano-British to the west and north.

Dover’s Cliffs in the Middle Ages

During the time of the Anglo-Saxons, a church was built at Dover, but the White Cliffs were not particularly utilized for the island’s defense. After centuries of Saxon rule, Britain was faced with a new group of invaders, the Normans. In 1066, William the Conqueror launched his successful bid for the English crown. While the bulk of the Saxon forces were far to the north, repelling an invasion by Harald Hardrada, William landed at Dover and soon overwhelmed the small garrison left there. A short time later, he would be victorious at the Battle of Hastings, securing himself the English crown. Knowing it was a vital strategic location, William and his descendants kept a permanent garrison at Dover. In 1160, Henry II began construction of a stone castle at the site, which would be the linchpin of the nation’s defenses.

While the White Cliffs of Dover were a formidable barrier against waterborne invasions, Dover Castle would play a major role against another threat. In 1216, barons, rebelling against King John, invited the son of the French king, Prince Louis, to invade England and establish himself as king of England, replacing the hapless John. He and a force of 700 ships would bypass Dover, landing further to the north, before capturing London. With the help of rebellious barons, Louis would eventually capture about half of England, mostly in the south of the country.

One bastion that held firm, however, was the castle of Dover, an island of loyalist support in a sea of rebellion. In spite of repeated attempts to take the fortress, the attackers only managed to topple one of the towers before being forced to withdraw. Due to this and other setbacks, the French prince failed in his bid to capture the English throne.

A More Peaceful Purpose

The White Cliffs of Dover would retain their status as the first land barrier of the British Isles, though they would no longer see any invasion force to repel, well almost. In 1660, after the Interregnum led by Oliver Cromwell, the exiled Stuart scion, Charles II returned to England to reestablish the monarchy. He landed at Dover, reportedly greeted by cheering crowds and the looming Dover castle firing its cannons in salute, welcoming their returned king to his homeland.

The next major threat that Dover and the White Cliffs faced was the possible threat posed by Napoleon Bonaparte. In preparation for a potential invasion, British military engineers carved tunnels and garrisons into the soft chalk of the cliff face. Poised to throw back the ambitions of the French, the White Cliffs were fortified, though, after the battle of Trafalgar in 1805, it was apparent that this threat would never materialize.

Though still a military installation, the White Cliffs became the site of other purposes. The world’s first electric lighthouse, the South Foreland lighthouse, was built in 1843. It was from this point that Guglielmo Marconi pioneered radio communication, receiving the first international radio broadcast sent from Wimereux, France. But the White Cliffs of Dover had one final military role to play.

Where Bluebirds Fly: Dover During WWII

In 1939, the British Admiralty dug a new operation center and a network of tunnels into the cliffs. Shortly after, the location was used to coordinate Operation Dynamo, the evacuation of the British army from Dunkirk after being surrounded by the Germans in 1940. After the evacuation, the White Cliffs were once again the first land barrier against a possible German invasion. As the closest point between Britain and the continent, it was an obvious location for an amphibious landing. The tunnel network was expanded, and extra defenses were put into place on the orders of Winston Churchill, who was enraged to see German ships plying the waters of the English Channel with impunity. Batteries of artillery were installed, which were used to attack German shipping. Long-range guns were used to bombard occupied Calais. Though Operation Sea Lion, the German invasion, never came about, the defenses at the White Cliffs were a major part of Britain’s wartime strategy.

Perhaps the most famous wartime use of the cliffs was not the rocks themselves but their symbolic meaning. For centuries, they were the last sight of their beloved homeland for leaving soldiers and sailors and the first sight on their return. Stark white stone jutting majestically from the sea, the White Cliffs became associated with Britain as a whole. It is even possible that the ancient name for Britain, Albion, is based on the word “alba,” or white. Now in their darkest hour, the cliffs became a symbol of resistance against the enemy.

In 1941, Walter Kent and Nat Burton composed the song “(They’ll be Bluebirds Over) The White Cliffs of Dover.” A version of the song would be recorded in 1942 by Vera Lynn and would soon become one of the most popular songs of the war. Incidentally, both Burton and Kent were Americans and did not know that there are no bluebirds in Britain. The migratory house swallow is sometimes called a bluebird by mistake and is often associated with spring and the promise of a more hopeful future. Many others, including Lynn, believed the bluebirds were a reference to the RAF fighter pilots who fought the Luftwaffe tooth and nail in the skies over Britain. The song was a major boost to morale, and the White Cliffs were, once again, a stand-in for Britain as a whole. They were the rock on which the security of the nation and the free world rested.

After the success of the Normandy landings, the defenses at Dover were no longer necessary and gradually dismantled. The cliffs eventually fell under the control of the National Trust, and the nation’s bulwark is now home to museums dedicated to preserving this important part of British history.