Cynicism goes beyond skepticism or negativity—it’s an approach to life that scrutinizes wealth, power, and society. It was first conceived by the Greek philosopher Diogenes, who spurned material goods by sleeping in a barrel and ridiculed social conventions. From Crates of Thebes to Friedrich Nietzsche and Henry David Thoreau, thinkers have long embraced Cynic notions of self-reliance and simplicity. Digital minimalism’s current vogue is just one example. Might this age-old philosophy also hold new solutions for those seeking to break free from modern distractions? Let’s investigate.

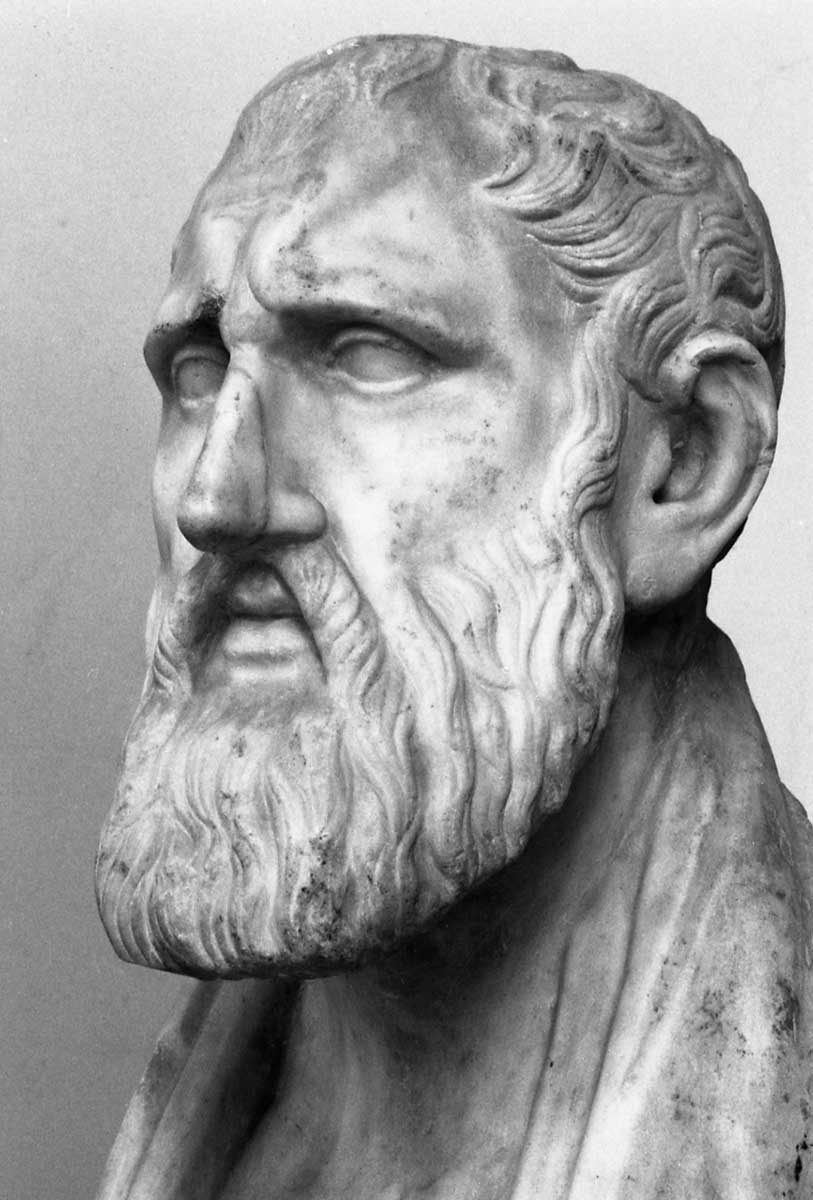

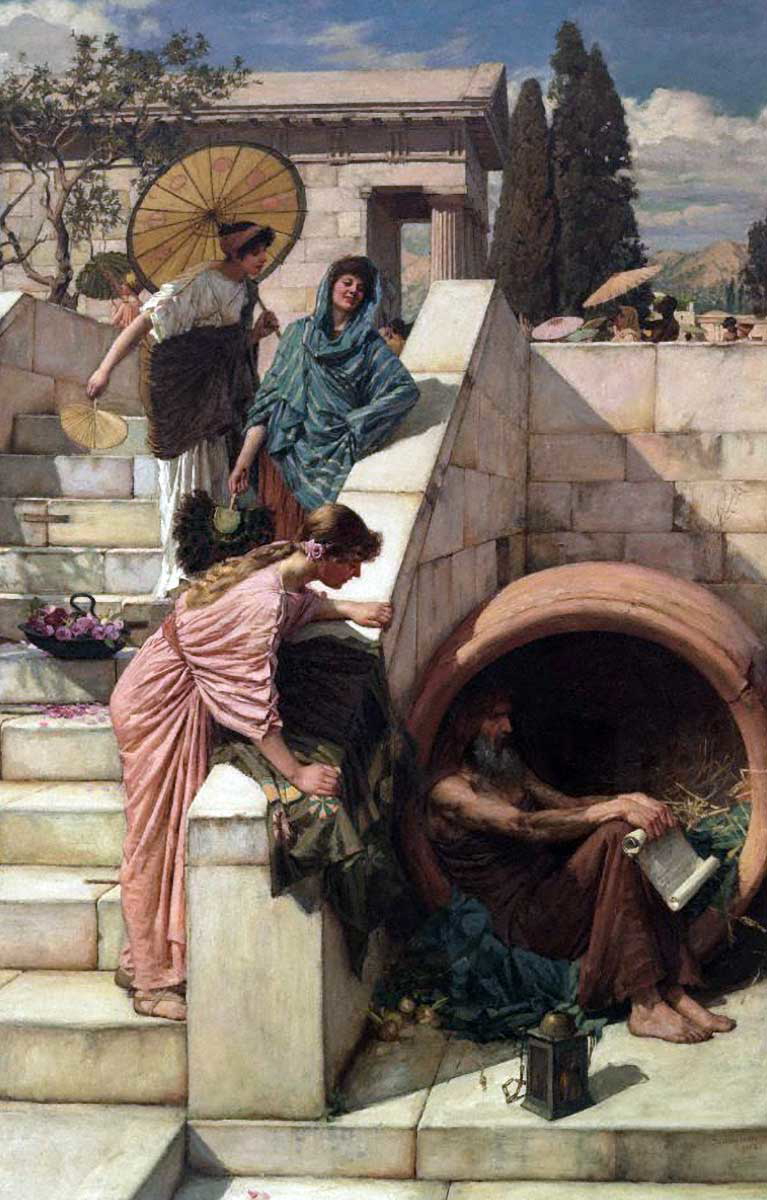

Diogenes of Sinope: The Original Cynic and Radical Simplicity

Diogenes of Sinope was not only a philosopher but a rebel against society itself. He thought people couldn’t be truly happy if they had to have things—like money, status, or power—that most folks found necessary.

Instead of following social rules like everyone else, he chose to live with almost nothing at all and believed this gave him more freedom than anybody else had.

How did he show this? Well, one example is when (it’s said) Diogenes went to live in a barrel—or maybe a big jar. He didn’t want to be comfortable; the way he saw it, luxuries just made us weak.

So when he noticed a boy drinking from cupped hands because he had no mug, Diogenes threw his own wooden mug away: after all, who needs such a thing?

Diogenes had no fear when it came to making fun of those in power. For example, once Alexander the Great said he could have anything he wanted, Diogenes replied: “If you can just stand a little to the side because you are preventing the sun. That will be enough gratitude, and I will remain thankful for my whole life.”

He believed everyone—whether a king or a beggar—would die, so why be obsessed with money? Live simply was his message: don’t get caught up in wanting stuff or always following the crowd.

It’s a way of life that still echoes today among people who practice anti-consumerism or turn their backs on traditional ideas of what makes someone successful.

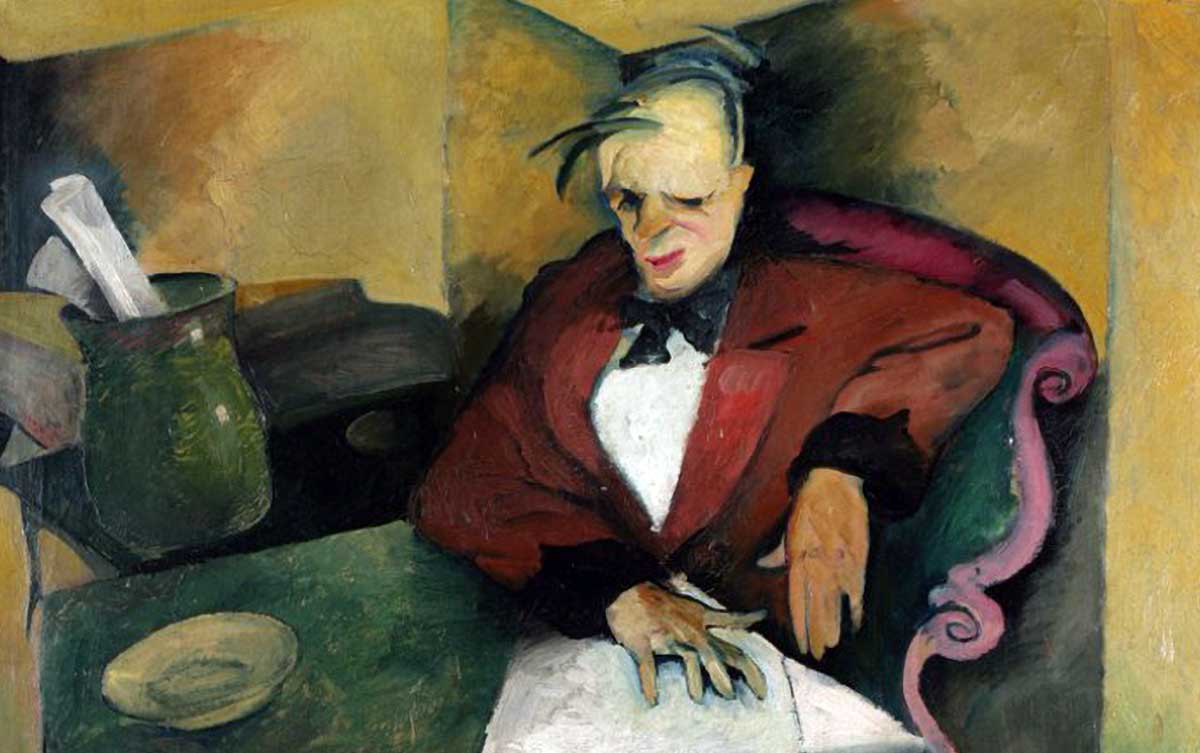

Crates of Thebes: The Joy of Voluntary Poverty

Although he had it all—money, prestige, and creature comforts—Crates of Thebes wasn’t content to rest on his laurels. He shocked everyone by simply giving his wealth away.

While many dread becoming destitute (and do their utmost to avoid it), Crates viewed poverty as liberty: if you have nothing, there is nothing you can lose. And it was Diogenes who opened his mind to this way of thinking.

With no cash concerns thanks to a radical change in circumstances, Crates happily went about his days with minimal material goods. Following in his teacher’s footsteps, he discovered the joy that comes from not being tied down by stuff.

Crates, in contrast to Diogenes, wasn’t harsh or argumentative— he was gentle, good-humored, and kind. He happily accepted his poverty, and people loved him for it. Although he wore rags, everyone welcomed him wherever he went (hence the nickname “the Door-Opener”).

Today, we still have time for Crates’s way of thinking. Many contemporary thought leaders advocate “less is more.” They tell us to downsize our material goods or chuck them entirely in favor of leading simpler lives that will make us happier.

If he were around now, Crates would snort at the idea that you could drive a top-of-the-range car, live in a penthouse apartment, or be rushed off your feet running big companies – yet still expect to feel cheerful all the time. He believed something quite different: By needing less, he said, you’ll set yourself free.

Zeno of Citium: Cynicism’s Influence on Stoicism

After losing everything he had in a shipwreck, Zeno of Citium went from being a rich trader to wandering the streets of Athens. There, he came across Crates and Diogenes’ ideas that challenged his beliefs about wealth.

These two philosophers helped Zeno see that real riches don’t have a monetary value—an insight that set off a profound change in his thinking. He wanted to build on their insights (which others also followed), so he began developing Stoicism. It was an influential school with a very different take on ethics and flourishing than those other schools had.

Stoics agreed with Cynics such as Crates not only in their diagnosis that most of us spend our lives worrying about things we can’t control, but also in suggesting an alternative: changing one’s perspective towards what happens.

Similar to the Cynics, Stoics also thought happiness did not come from having a lot of money or a good reputation but from controlling your attitude to life.

They agreed that you should not be upset by things that are outside your own mind, such as whether you have wealth and possessions, are famous, or even comfortable. What matters is how you deal with situations and stay calm inside.

However, Zeno’s version of Stoicism was different in some ways from the Cynics. While Diogenes laughed at ordinary people and their rules, those who followed Zeno did try to live like this, but in a careful, thoughtful manner.

Today, this philosophy can help us live better in a number of very practical (useful) ways—for example, when we take breaks from social media or learn how to bounce back from disappointment.

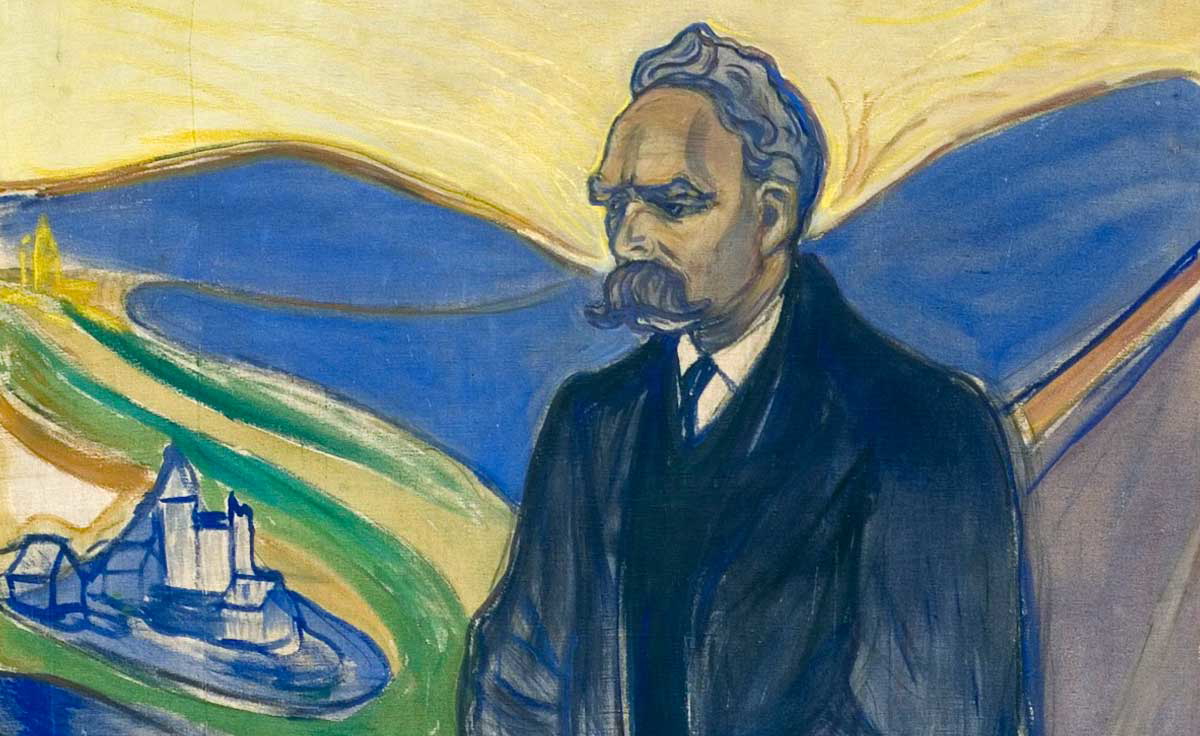

Friedrich Nietzsche: The Cynical Critique of Modern Morality

Friedrich Nietzsche, a philosophical rebel much in the manner of Diogenes, did not think people should slavishly follow social rules, traditional codes of conduct, or crowd mentality—and he made trouble by saying so.

Like the Cynics, Nietzsche thought most individuals drift through existence as part of a passive herd: they do what feels comfortable, strive after unchallenging lives, and never stop to ponder deeply about anything.

Again, like all Cynics and some Cynics only, Nietzsche believed one could live better by vigorously opposing such artificial or superficial values.

Indeed, he went further. He claimed that his notion of Übermensch or “Overman” corresponded to the ancient ideal wise person who was entirely selfsuflicient and able to make up their own mind about how they wanted to live.

Today, Nietzsche’s ideas remain relevant. If he were alive now, he might think we’re all still slaves to trends, likes, and pop culture—just digital ones. Why not do your own thing instead of joining the herd? This is a question both he and the Cynics would ask today.

There is an emphasis on being true to yourself and working out who you are in the world, which chimes with current concerns about TV, magazines (both things Nietzsche despised), and looking for serious meaning behind sometimes transient fashions (again, not stuff he liked).

Nietzsche wants to challenge people to live more actively and not just consume things passively, which is also a bit like what those Stoics would have said is wise.

Henry David Thoreau: Living Deliberately and Rejecting Excess

Henry David Thoreau was much like a Diogenes for his time, but instead of living in a barrel, he built a small cabin in the woods. He believed most men led fake, shallow lives, always chasing money and material things.

To escape this trap, for two years, he went to Walden Pond and tried living there with as few possessions as possible while writing, thinking, and talking to nature. Thoreau’s philosophy can be boiled down to this: say no to things and activities you don’t need, so you can say yes to relying on yourself and making careful choices.

By cutting out things that aren’t essential to life, Thoreau thought people could better understand what being alive really meant and see its simple beauties more clearly. Like the Cynics before him, he thought needing less felt freer than having or wanting more.

His concepts are very similar to those of today’s minimalism and slow-living movements. Many individuals feel swamped by their busy jobs, constant digital intrusions, or society urging them to buy more and more stuff.

Nowadays, Thoreau’s advice about how to live a good life—simplify, take time out, concentrate on the important things—lies at the heart not just of ancient philosophy but also concerns such as digital detoxing, sustainability, and mindful consumerism.

Had Thoreau lived in the present day, it is likely he would caution against becoming addicted to social media and constantly striving for more money and material goods.

Instead of asking about which clothes to wear or jobs to do next, he would ask whether we need all this gear and suggest ways to find peace without constantly buying more.

Digital Minimalism: Cynicism in the Age of Technology

Consider how Diogenes would react to owning a smartphone; Newport suggests he would dispose of it. Like the ancient Cynics who rejected wealth, modern-day Cynic Cal Newport believes that too many people are unhappy because they have become slaves to their gadgets.

Newport’s philosophy can be seen as an updated version of Cynicism that stresses self-sufficiency and the importance of avoiding things that hamper you in your life. For him, digital minimalism isn’t about doing everything online as quickly as possible, or constantly checking social media so FOMO doesn’t creep up on them.

If we want to live good lives in today’s connected world, then one way might be to take advice both from Newport and some long-dead Greeks: think carefully before using any form of technology. Don’t just let it use you!

Newport suggests that individuals should reduce their usage of social media. Instead, he wants them to concentrate more intensely and live in the real world rather than get hooked on notifications or short-term pleasures. Like the Cynics, freedom for Newport means being able to ignore society’s expectations.

His advice is simple: we should be using technology. It shouldn’t be using us. In an age when paying attention is increasingly difficult, digital minimalism—practicing being online less often but making each visit more purposeful—could well turn out to offer freedom for modern times, comparable to what Diogenes had when he chose to live in a barrel.

So, if Diogenes were around today, would he be a fan? Yes, probably—although he might describe it as having “Wi-Fi-free wisdom.”

So, What Is Cynicism Today?

Cynicism has evolved over time, from Diogenes’ barrel to digital minimalists’ rejection of online distractions, but its essence remains the same: question everything, shun unnecessary excess, and seek authentic freedom.

Whether in Crates giving away his fortune, Thoreau retreating to Walden Pond, or Cal Newport urging less screen time, Cynicism challenges consumerism, conformity, and superficiality to date.

Its core concerns—independence, plain living, seeing through societal deception—resonate well in an era of non-stop alerts, binge buying, and curating your best self on the internet. In effect, today’s cynics ask: do we really need this stuff?

But can one lead a genuinely Cynical life nowadays? Could you go offline and off-grid like Diogenes in a world that relies on tech necessities and constant connectivity, or are we all caught up in it too much to break free? Perhaps the trick lies in selecting what you reject and hanging onto what you hold dear.