Many of the desert expeditions that cemented the outback as the defining and feared feature of the Australian psyche were ill-fated. The lives of the men who led them were cut short. Ludwig Leichhardt disappeared and is likely to have died somewhere in the Great Sandy Desert. Robert O’Hara Burke and William John Wills died of malnutrition in south-west Queensland after crossing Australia from south to north. Other surveyors and explorers, such as Alfred Canning and Ernest Giles, survived and lived to see their names become entwined with Australian topography and history forever. It was their determination that shaped Australia as we know it today, for better or worse.

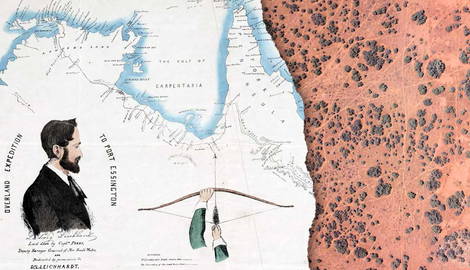

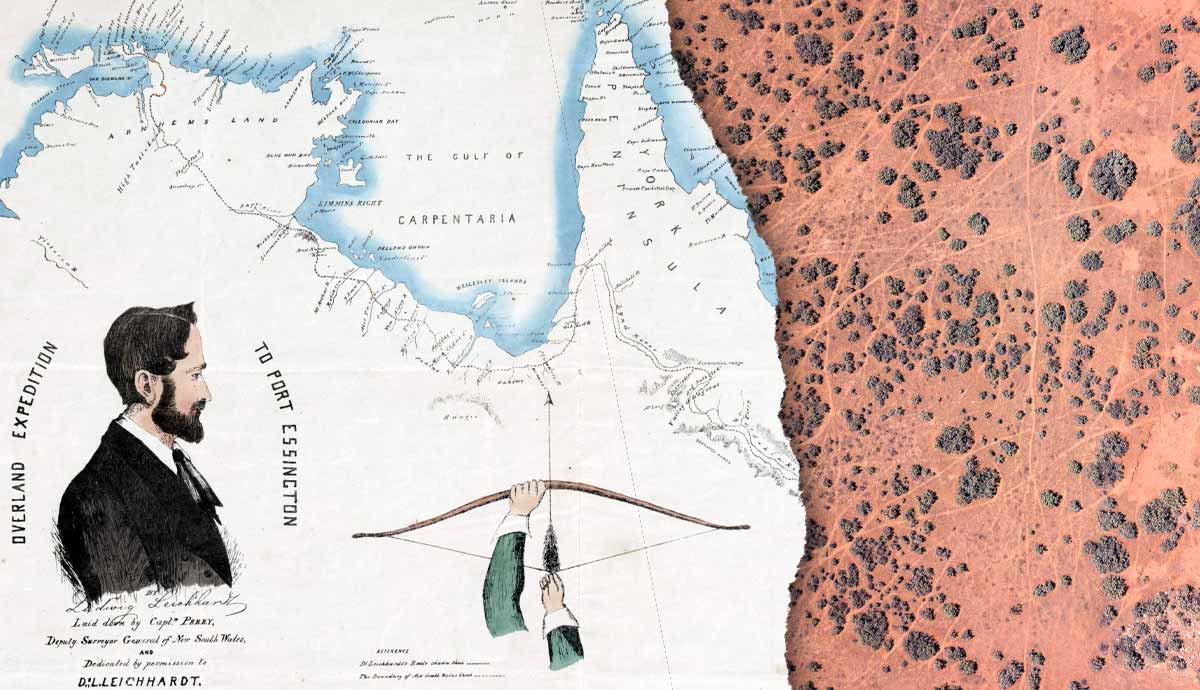

Ludwig Leichhardt, Lost in the Desert

Ludwig Leichhardt vanished in the Australian Outback at the age of 35. So did the seven other members of his expedition, along with their seven horses, 20 mules, and 50 bullocks. The year was 1848, and this was Leichhardt’s third expedition into the Australian interior.

Leichhardt came from Prussia. A scientist and naturalist, he was a member of the European intelligentsia, educated at some of Europe’s most prestigious universities, including Berlin and Göttingen, where he studied philosophy, foreign languages, and eventually natural sciences. Australia, with its unique geology, vegetation, and fauna (the home of people now acknowledged as having the oldest continuous culture on Earth), represented a goldmine for Leichhardt. Here, he quickly established himself as the “Prince of Explorers,” an educated European hero dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge in all its forms—a perfect blend of science and exploratory drive. Many of his contemporaries called him “the Doctor,” even though he never actually earned his university degree.

Two years after arriving in Australia on February 14, 1842, Leichhardt embarked on his first expedition (1844-1845). By this time, he had already travelled extensively across the country, mapping it, collecting rock specimens, and making extremely accurate and scientific observations of what he saw and believed was worth studying.

His first expedition took him from Sydney to Port Essington, north of what is now Darwin. With his team, Leichhardt set out from the Darling Downs, a fertile farming region in southern Queensland, crossed Arnhem Land, skirted the shores of the Gulf of Carpentaria, and entered the Alligator Rivers region, carefully noting the region’s fauna and flora and the red ochre animal drawings on rocks made by local Aboriginal groups. Among his companions was also John Gilbert (1812-1845), the collector for English naturalist John Gould.

During the final stretch of the party’s journey, some Aboriginal men, some of whom understood and spoke a little English, supplied Leichhardt’s men with water and food, and even gave them directions.

Overall, the party covered 4,827 kilometers (3,000 miles). After completing this first expedition, which was praised by geographical societies in London and Paris, as well as local investors, Leichhardt turned his attention west. He planned to cross Australia from the Darling Downs in the east to the Swan River region in what is now Western Australia. Aware of the dangers of Central Australia, he planned to skirt its northern limits. First, he would lead his men across the Top End, then they would follow the northern coast of Western Australia, eventually heading south to what is now Perth. The party set off in December 1846, carrying 108 sheep, 270 Tibetan goats, 40 bullocks, as well as horses and mules. What Leichhardt didn’t (and couldn’t) take into account was rainfall.

The rain bogged down the animals, slowed the men, and destroyed their tents. Many were weakened by fever, and others were bitten by paper-nest wasps. The expedition was called off in June 1847. The party had covered some 805 km (500 miles).

The failure of the Darling Downs expedition prompted Leichhardt to organize a third expedition. He did not realize it at the time, but this marked the beginning of the end—the end of his life and the creation of the myth.

Leichhardt was last seen alive on April 3, 1848, at Coogon Station, which was the most westerly grazing property on the Darling Downs and was owned by Allan McPherson. McPherson and two of his workers met the expedition at a waterhole to the west of the station. One of them reportedly asked Leichhardt where he was headed. Leichhardt reportedly replied: “To the setting sun.” He and his party then disappeared, taking their animals, rifles, axes, knives, telescopes, and pots and pans with them.

Burke & Wills, From South to North

Just over a decade after Leichhardt’s disappearance, two other explorers died alone, malnourished and weakened by exposure, within a few days of each other in June 1861 beside Cooper Creek, an ephemeral watercourse in Queensland. Their names were Robert O’Hara Burke and William John Wills. They had just become the first Europeans (Burke was Irish, from County Galway, and Wills was British) to successfully cross the Australian continent from the deep south to the north.

On August 20, 1860, they departed from Royal Park in Melbourne with their 27 camels, 23 horses (or 27, according to some sources), and a crew of 19 men. A large crowd of around 15,000 people watched the camels make their way out of Melbourne, laden with tons of firewood, two years’ worth of rations, an oak table, and 50 gallons of rum.

One month later, on September 23, the expedition had reached Menindee, near Broken Hill, the first town to be established on the banks of the Darling River and the oldest European settlement in far western New South Wales. Most of the equipment and the supplies were left there under the supervision of William Wright, a local station manager, while Burke set off with a smaller party for Cooper Creek, in Queensland. After establishing a depot here, he split the party once more.

William Brahe had emigrated to Australia from his native Germany at the age of 17 in 1852. In Victoria, he followed in the footsteps of thousands of other European immigrants by taking up various jobs, working alternatively as a drover, a storekeeper, a wagon driver, and a gold digger. The turning point in his life came when he joined the Burke & Willis expedition.

Burke left him in charge of the depot at Cooper Creek before departing for the Gulf of Carpentaria with three of his men: Wills, a Scottish sailor and former gold miner named Charles Gray; and an Irish soldier named John King.

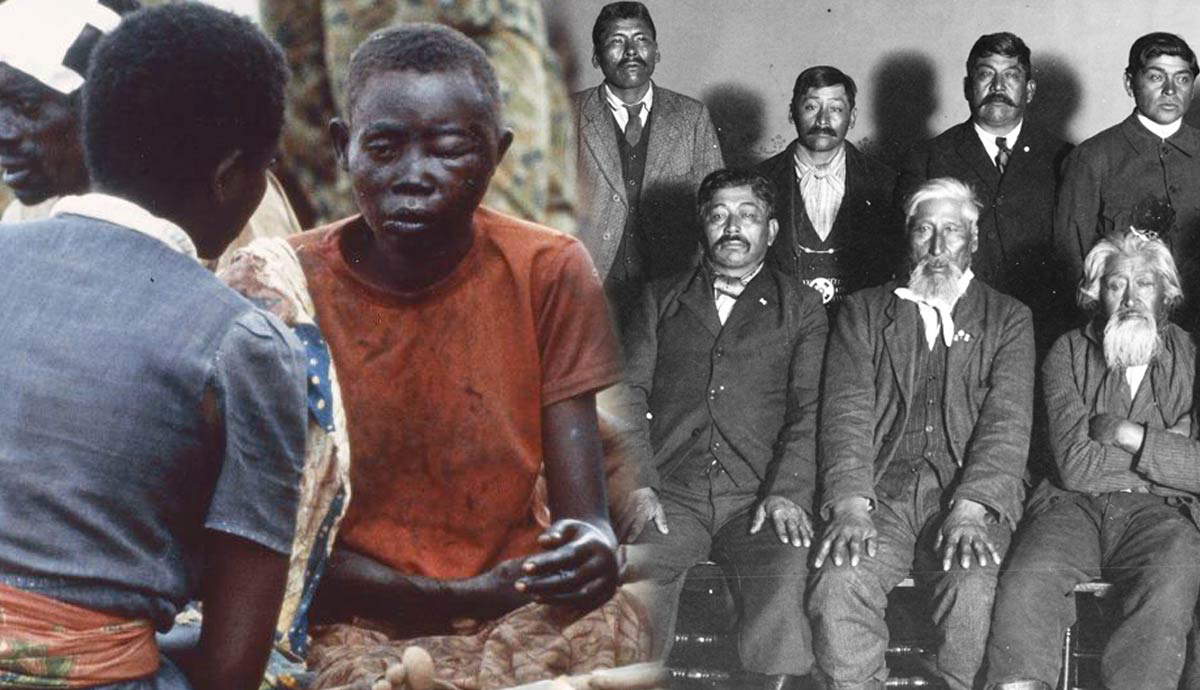

After crossing the Sturt Stony Desert, a barren and dry expanse of gibber pebble plains, ephemeral salt lakes, and dunes in north-eastern South Australia, they reached the Gulf of Carpentaria off the northern coast of Australia in February 1861. They never saw the open ocean. Between them and the water was an expanse of mangrove swamps. On their way back to Cooper Creek on April 17, Gray died of malnutrition. Of the four men who had reached the northern coast of Australia, only John King survived.

The Yandruwandha people—the Traditional Land Owners and Custodians of a large geological area known as Cooper Basin—came to his rescue and accepted this white man, born on the other side of the world, into their community. He lived with them on their ancestral lands for two and a half months, until Alfred Howitt’s relief party finally found him on September 15, 1861.

Alfred Canning and the Canning Stock Route

The Canning Stock Route is many things: a lifeline and a nightmare; an incredibly ambitious piece of infrastructure and an illusion of human grandeur. Its history and value change depending on who is telling its story. Snaking its way through 1,850 km (1,150 miles) of rugged and dry land from Halls Creek in the Kimberley region of Western Australia to Wiluna, a small town in the Goldfields-Esperance region, the Canning, as it is known, is the repository of an unsettling truth. In a post-colonial country, nothing exists outside the framework of colonial dynamics, not even a trans-desert stock route.

In 1906, Alfred Wernam Canning (1860-1936), a 46-year-old surveyor with the Western Australian Department of Lands and Surveys, was appointed to lead a survey expedition through the region’s major deserts, the Little Sandy Desert, the Gibson Desert, the Great Sandy Desert, with its vast red sand plains, spinifex expanses, rocky outcrops, and dune fields, and the Tanami Desert in the far north.

Following in the footsteps of Lawrence Allen Wells (1860-1938) and David Carnegie (1871-1900), who had crossed those very lands a decade earlier, Canning departed with eight men, two horses, and 23 camels. The expedition’s motives were practical: it had its roots in the spread of the Boophilus ticks and the tick-borne disease they transmitted—a malaria-like illness introduced to northern Australia in the 1870s, likely via Indonesian cattle, that had then spread like wildfire through the Kimberley region.

Fearing further transmission, the government prohibited East Kimberley cattlemen from transporting their cattle to southern markets by sea via the ports of Darwin, Derby, or Wyndham. This measure effectively shut down East Kimberley graziers, leaving West Kimberley pastoralists with a near monopoly on the southern beef trade. It was at this point that the idea of a trans-desert stock route came into being.

The disease, also known as “redwater fever,” earned its name from one of its most dramatic symptoms. Driven by the fever and discomfort, infected cattle reportedly sought relief in rivers and waterholes, where their blood-tinged urine turned the water red. The sight of their cattle stranded in creeks and waterholes, surrounded by reddish-brown water, prompted pastoralists to call the disease “redwater fever.” It also prompted them to lobby the government to build a trans-desert stock route that would connect them to the markets of Perth, bypass quarantine restrictions on sea transport, and break the cattle trade monopoly that their neighbors in West Kimberley had managed to establish.

It was believed (and later validated by veterinary science) that the dry desert climate along the stock route would kill the ticks naturally, freeing the cattle and their owners from the disease. The desert, feared for its unforgiving nature, became a resource, an ally in quarantine strategy.

So too did the “natives,” the desert people, the Aboriginal trackers and guides, sometimes chained by the neck, that Canning and his team used to locate wells and waterholes, essential for obtaining approval to build the route. Many of them were also sacred to their Traditional Custodians.

This is how the Canning Stock Route came into being, a project that so deeply impacted the lives of at least 15 Aboriginal language groups, including the Martu, the Walmadjari (Walmajarri), and the Wangkajungka. Today, their stories and those of their descendants are finally being told. A different perspective on the Canning Stock Route, more inclusive, nuanced, and complex, has finally begun to circulate.

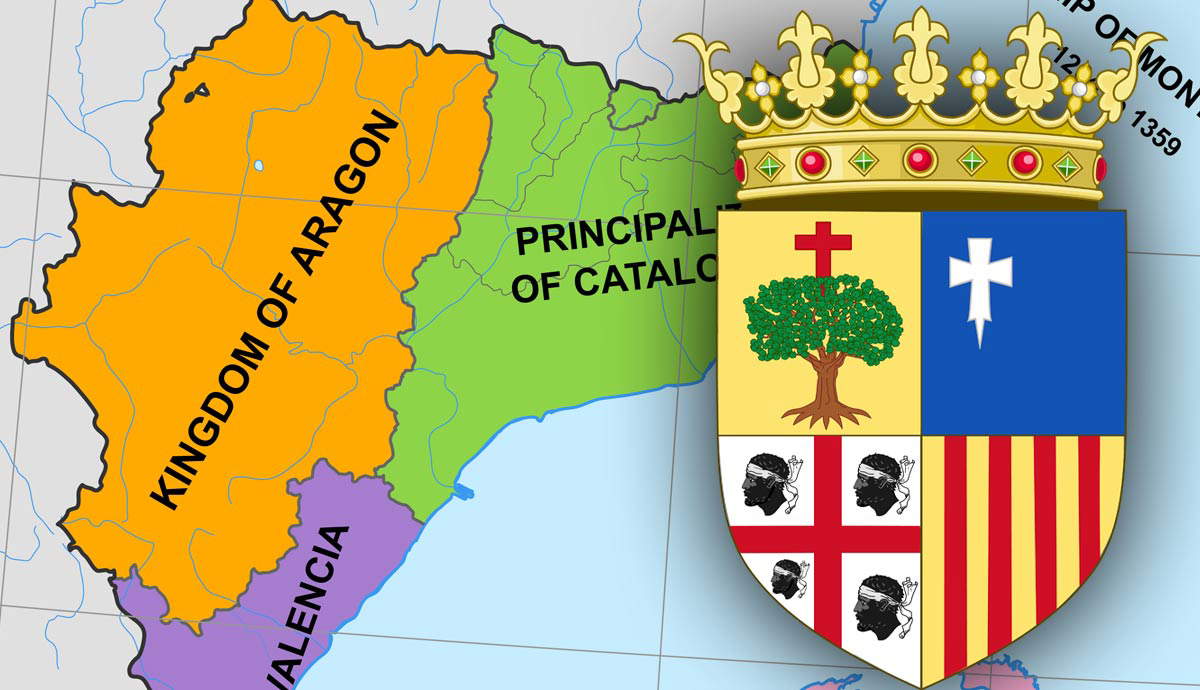

The Burke & Wills expedition, officially known as the Victorian Exploring Expedition, proved that the Outback, the uncharted and feared Australian interior, could be crossed. It showed (white) Australia that if the Outback could be crossed, then it could also be settled. And if it could be settled, it could also be exploited.

While the solitary and tragic deaths of Burke, Wills, and Charles Gray appeared to confirm what many settlers feared, they also, ironically, stripped the Outback of some of its mystique. The same can be said of Ludwig Leichhardt’s various expeditions and Alfred Canning’s journey through Western Australia’s deserts, which together facilitated the expansion of European settlement into central Queensland and northern Australia and opened up the interior to pastoralists and their fever-stricken cattle.

The many expeditions into the Red Heart that punctuated the 19th and 20th centuries also contributed to the (re)naming of the continent we now call Australia. Two suburbs and a highway in Queensland are named after Leichhardt. The Canning Stock Route, as well as the Federal Division of Canning, are named after Alfred Canning. Rivers and creeks throughout Queensland commemorate the lives of Burke and Wills. John McDouall Stuart, whose various expeditions between 1858 and 1862 laid the groundwork for the Overland Telegraph, is honored by McDouall Peak in South Australia and the Stuart Highway.

As they laid the foundations for the infrastructure that would connect Australians from all parts of the country, these men—along with their Aboriginal guides and trackers—were also shaping the nation’s identity, history, and culture.