Approximately 11,000 years ago, in the Pleistocene epoch, humans began to enter present-day South America. There, they came face to face with the giants of their day—ground sloths over 20 feet long, armored glyptodonts the size of a car, and felines with foot-long teeth. Their close proximity meant that humans often came into direct contact with megafauna. In fact, some studies suggest that human hunting may have contributed to the extinction of many of these enormous animals.

South American Megafauna: A Diverse Bunch

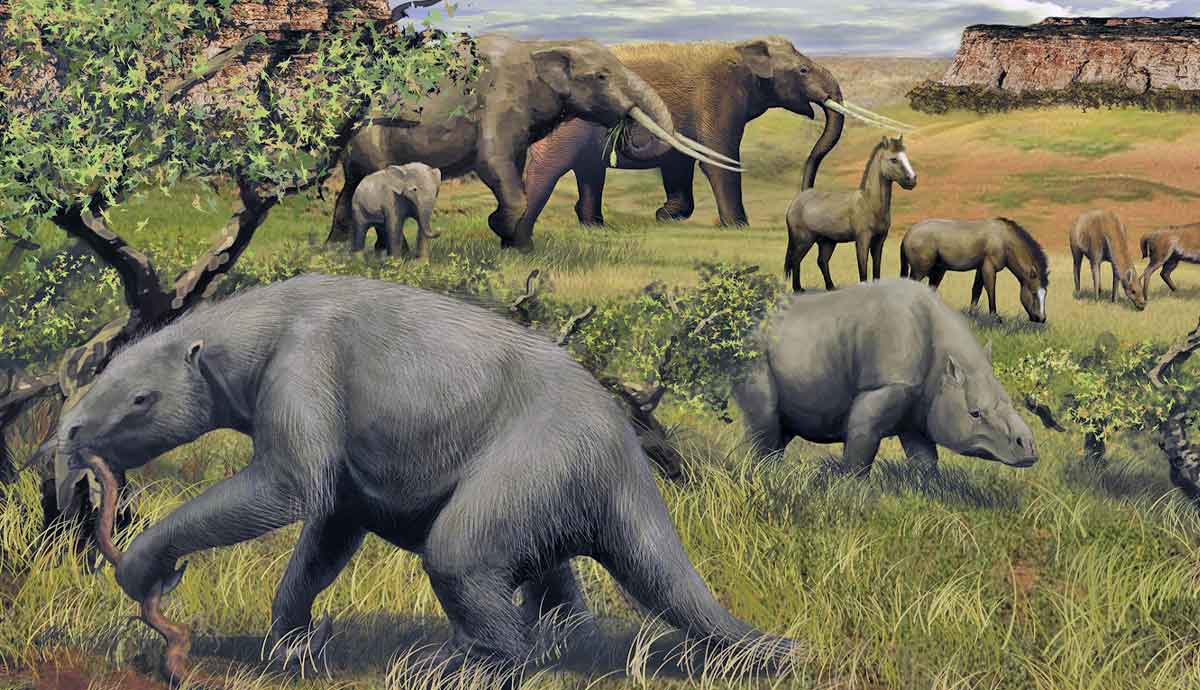

The appearance of megafauna in South America began in the Pliocene Epoch of about five million years ago. Aided by the emergence of the Isthmus of Panama from the sea, which allowed for the Great American Interchange, animals began migrating north and south over the continents. Though mammoths and mastodons remained confined to North America, South America was populated by hundreds of species of huge mammals.

One such creature, called a glyptodont, was like a prehistoric version of an armadillo that weighed around 2 tons. Some other notable creatures include Megatherium americanum, a giant ground-dwelling version of the sloths that live in South America today, as well as oversized llamas, capybaras, bears, felines, and canines. Though horses were introduced to South America by European conquistadors, they once existed there before their extinction in the late Pleistocene. By 10,000 years ago, over 25 different types of megafauna had evolved within South America.

Humans began to enter South America between 15,000 and 20,000 years ago during the late Pleistocene. These early South Americans, sometimes referred to as Paleoindians, were hunter-gatherers who moved their settlements as they followed their prey. While past sources argued for an overland route through the middle of the Americas, new research shows that the most likely migration pattern was a route along the Pacific Coast. During the Pleistocene, the world began to experience a great cooling, which led to increased diversity among the megafauna. However, shortly after this cooling stopped, and after humans arrived, the fossil record shows a great decline in the biodiversity of South American megafauna.

Campo Laborde, A Wildlife Refuge?

Campo Laborde is located in the Pampas region of Argentina, near the city of Olvarría, and some researchers claim it contains evidence of the hunting and butchering of the giant ground sloth, Megatherium americanum. At this site, researchers found a host of faunal bones, as well as the remains of early stone tools that Paleoindian hunters would have used. When the rib bone of an M. americanum specimen was found with cut marks, researchers began to consider the possibility that pre-historic South Americans had hunted the animal. Other bones from both M. americanum and other mammals were also found, often in close proximity to cutting and scraping tools.

The bone dated to about 6,000 to 9,000 years ago, which is much later than the previously proposed dates for the extinction of M. americanum. Some researchers suggest the Argentinean Pampas, vast food-rich prairies, could have been a refuge for the last of the South American megafauna. The presence of animal bones and tools, coupled with the lack of evidence of habitation, have led researchers to believe that this area might have been used as a butchering site by Paleoindians. M. americanum and other species of megafauna may have been hunted at this site, cut up into manageable pieces, and then brought back home to be eaten.

Megafauna Remains at Arroyo Seco

The Arroyo Seco site is another Argentinian location where evidence of early human habitation and possible hunting of megafauna were discovered. At this site, the remains of 14 Pleistocene animals were discovered, as well as at least 50 human burials from between 7,000 and 4,000 years ago. The discovery of several stone tools buried amongst the bones of a sloth, horse, and camel led researchers to believe that this could have been another site for the hunting and butchering of megafauna. Some postulate that the tools would have been used to disarticulate bones, allowing for easier butchering and transport. However, one important detail to consider about this site is that no arrow points were found. This prompted researchers to hypothesize that Arroyo Seco, unlike Campo Laborde, was only used for butchering and not for hunting. Though many of the stone tools discovered would have been used to break down the animals, some of them are consistent with those used for preparing hides.

In addition to the discovery of the faunal bones, the purported activity at this location also provides insight into the distances Paleoindians would travel for sustenance and materials. An analysis of some of the tools revealed that the stones they used came from more than 90 miles away. Further studies of the cut marks on the bones were carried out, comparing them to the marks made by modern hunter-gatherers. These tests revealed that these people would have hunted cooperatively, working together to take down sloths large enough to crush an adult man. Another strange discovery at Arroyo Seco was that the bones of the skull and mandible were often left behind. This suggested that Paleoindians valued the body of these creatures more as the meat could provide much-needed sustenance.

Arroyo del Vizcaíno and Dating Controversies

The Arroyo del Vizcaíno site, located in Canelones, Uruguay, provides further examples of Paleoindian interactions with megafauna. At this site, the bones of a giant sloth of the genus Lestodon were found exhibiting marks that suggested humans had been involved in its death. The marks included chopping, sawing, and scraping motions that are comparable to those made by human stone tools. Like other sites, the remains of stone tools that could have possibly been utilized in the butchering process were found in the same area.

One thing that separates this site from others is the fact that it dates to nearly 30,000 years ago. Some researchers began to use this discovery to claim that Paleoindians had arrived in the Americas much earlier than originally believed. And this site is not the only one dated to periods that are incompatible with current hypotheses on human dispersal in the Americas. The Toca do Boqueirao do Sitio da Pedra Furada site in Brazil dates to 40,000 years ago, and the Monteverde site in Chile dates to over 14,000 years ago.

However, recent work by some researchers has attempted to disprove the proposed evidence of humans inhabiting the Americas so early. They point out that the marks on the bones could have been a result of natural processes taking place after its death. They also note that errors in the calibration of the carbon dating could have led to a false reading.

Humans v. Megafauna

For years, researchers have been working to understand what exactly led to the extinction of megafauna in South America in the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene periods. When the above sites were discovered, some began to speculate that humans could have played a part in the disappearance of these giant beasts. Radiocarbon dating has shown that most megafauna began to die out around 7,000 years ago, 3,000 years after humans appeared on the continent. Many wondered if this 3,000-year period, coupled with the intelligence, endurance, and ingenuity of humankind, could have given Paleoindians an edge over megafauna.

One study found that as humans in South America developed a new kind of arrowhead called a fishtail point, there was a significant drop in the populations of megafauna. The appearance of fishtail points was also accompanied by a rise in the human population of these areas, suggesting that the point made humans more successful in hunting megafauna, and therefore more equipped to support larger populations. All of this seems to suggest that humans caused the extinction of South American megafauna.

However, newer research suggests that megafauna actually went extinct due to a complex mix of reasons, with humans playing only a small part. During the 3,000-year window of coexistence between human and beast, the climate of South America underwent a great change. Weather oscillated between warm and humid and cold and dry, with little time for these animals to adapt. Some megafauna had already gone extinct long before the arrival of humans due to the changing environment.

New hypotheses agree that the impact of human hunting combined with the changing weather meant that megafauna were often subject to heightened competition for food and land. Some researchers even suggest that since these creatures did not evolve alongside humans like those in Africa and Eurasia did, they had no instincts to avoid them. This would have made them easy prey for hungry humans looking for a meal. With little real evidence of the overhunting of megafauna, early South Americans are slowly being exonerated.