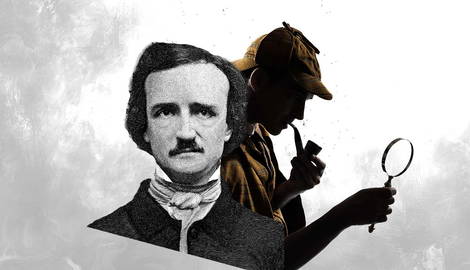

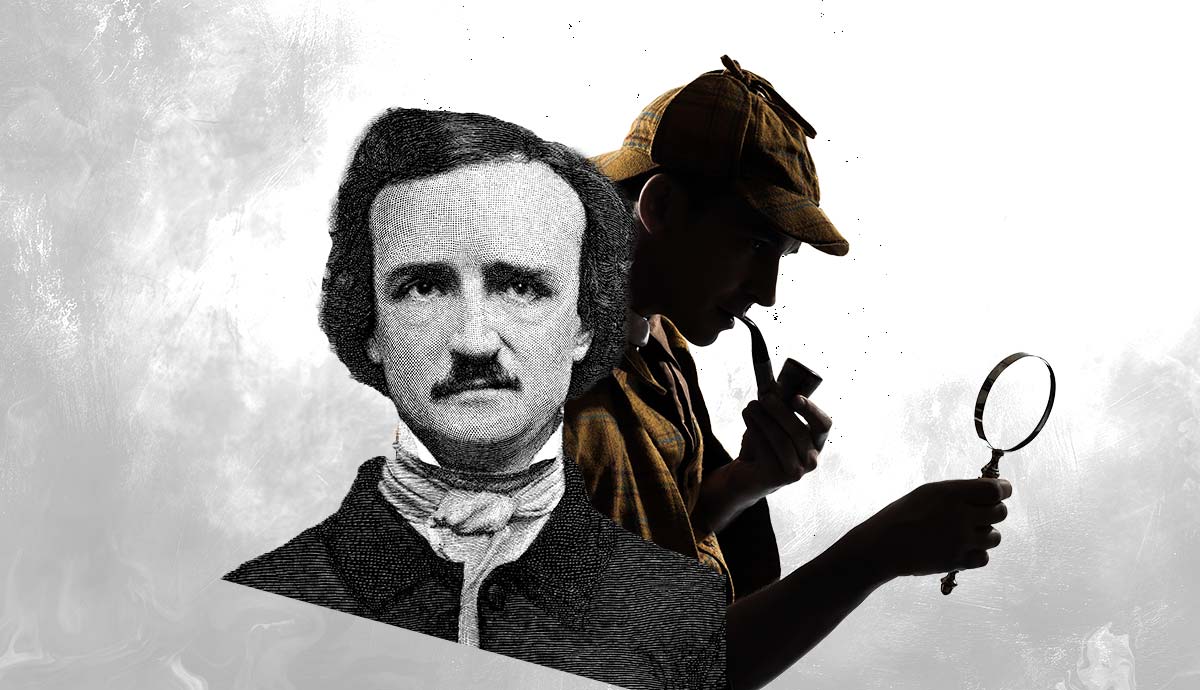

While a cohort of 19th-century European writers were instrumental in fashioning and figuring out the detective story on paper, Edgar Allan Poe is invariably attributed as its first great mastermind. Poe’s 1841 “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” was the first of his tales of “mystery and imagination” that featured his brilliant amateur sleuth, Paris’ C. Auguste Dupin. Fifty-odd years later, Arthur Conan Doyle himself revealed and duly saluted Dupin as the leading literary inspiration for his own ratiocinating, crime-solving gentleman genius, London’s Sherlock Holmes.

From Edgar Allan Poe to Poirot: Tracing the Roots

As is typical with most inventions or innovations, they are rarely the product of any one person or intellect. Instead, they just as frequently evolve out of the zeitgeist or spirit of the times. In the case of detective (or police) fiction, many authors in both France and England aided and abetted the entrance of cerebral, crime-crushing gumshoes, from Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot (with his “little gray cells”) to U.S. TV’s Colombo, the rumpled police investigator memorably played by Peter Falk.

A scrupulous literary historian would back-track millennia and investigate Sophocles’ classic Greek play Oedipus Rex to find an ancient footprint of detective fiction. After all, it’s the doomed King Oedipus who methodically solves the mystery of who slayed his father—summoning and questioning witnesses, searching for clues, uncovering secrets—before tracing this timeless “cold case” right back to his own palace. Likewise, in an Elizabethan sequel of sorts, Shakespeare’s Prince Hamlet is tasked to search out and take revenge on the assailant who killed his father. If there is a working motto to the detective-hero, it might be Hamlet’s “Though this be madness, yet there is method in it.”

Cops, Flics & Bobbies

However, historians tend to argue that the emergence of the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s set the stage for what would become detective fiction. With textile and mill workers, among others, flocking to cities from small towns and rural areas, conditions were being created not just for dense overcrowding but also for impersonal crimes among the hordes of strangers. Or take the simple issue of street lighting—typically a discouragement against crime and mischief.

Until these bustling cities in Europe and America were lit up at night (first by gas, then via electricity), entire blocks would sit in darkness away from the main thoroughfares, thus inducing a milieu for victims, especially women (the notorious example here, of course, being the horrific “Jack the Ripper” slayings in 1888-91 London). Compounding the problem, well into the 1800s, most cities had no organized or professional police forces; the streets were “policed” only in insular local areas surrounding church parishes, typically by volunteers, and seldom at night.

“Crime waves,” especially in poor and immigrant areas, were rising, if not crashing into these teeming metropolises. While London was one of the first large Western capitals to create its own police force (1829), followed by Boston (1838) and New York City (1845), Paris had a form of municipal policing much earlier. During Louis XIV’s reign, the office of the Lieutenant General of Police (established in 1667) managed public order, markets, and regulations, but it was largely administrative rather than a uniformed, street-patrolling force. However, it wasn’t until the early 1800s that Paris had the semblance of a lasting police unit, complete with both uniformed and plainclothes officers. And with that, The Collector’s trail leads to the West’s first true-crime detective-hero, France’s Eugène-Françoise Vidocq (1775–1857).

After a crooked life in and out of prison, in 1809 Vidocq “went straight”—that is, right into the offices of the Paris gendarmes, who, in the “it takes a thief to catch a thief” mold, would eventually hire him to head up a new plainclothes investigative unit. While his methods and ethics would attract scrutiny, there’s no question his record of front-page arrests made him a legend, further enhanced by his ingenious development of modern policing methods such as forensics, criminal “rap sheets,” and fingerprinting. He is also credited with opening the first private detective agency in Paris in 1832.

The Detective Detected

Not only was Edgar Allan Poe an avid reader of Vidocq’s three volumes of memoirs (1828-29), but he even gives him a shout-out in “Murders in the Rue Morgue.” Vidocq would provide a thick dossier of story fodder for a number of celebrated French novelists, from Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas pere to Honoré de Balzac. One only needs to eyeball the relentless, merciless Inspector Javert from Hugo’s timeless crime-manhunt epic Les Misérables (1862) to find evidence of policier twists and turns in 19th-century Continental fiction. At the same time, across the English (or is it French?) Channel, Charles Dickens was also exploring these budding narrative archetypes, for instance in his novel Bleak House (1853), which traced the exploits of Scotland Yard’s extraordinary Inspector Bucket.

It’s normally dicey business to retrospectively claim historic “firsts,” literary or otherwise, but Poe’s “Rue Morgue” is invariably credited as the first published short story with a plot almost exclusively constructed around a sleuthing protagonist. Furthermore, the adventures of M. Dupin (also followed up in several sequels, including “The Mystery of Marie Roget”) would provide plot and characterization modus operandi for scores of worthy imitators, perhaps most impeccably Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in his phenomenal and still popular Sherlock Holmes cloak-and-dagger mystery novels and stories. How, precisely? In “Rue Morgue,” from the moment “the game is afoot,” readers can’t help but spy uncanny similarities between its two central characters and their virtual doppelgangers from the pen of—and according to—Doyle.

Partners in Crime … Solving

So, in the famous words of Sgt. Joe Friday from the old Dragnet TV series, let’s do a rundown of “just the facts, ma’am” to outline Poe’s long shadow over this popular literary genre. It’s perhaps most obvious and elementary in Doyle’s A Study in Scarlet, his 1887 novel that quietly introduced the world to the remarkable Mr. Holmes.

- Much like Holmes’s incipient sidekick Dr. John Watson, Poe’s (unnamed) narrator relates the story and introduces the reader to Dupin, his nouveau compatriot, a brilliantly eccentric and reclusive “young gentleman” of Paris. Moreover, just as Holmes and Watson agree to room together, famously, in their 221B Baker Street London flat, Dupin and his chronicler do the same, sharing a (“time-eaten and grotesque”) mansion in the Faubourg St-Germain district.

- Both narrators are flabbergasted when their respective counterparts seemingly “read” their minds, or at the very least display a preternatural knowledge about them. In Poe, Dupin and his new chum are out strolling one night, mute for minutes on end, when Dupin suddenly and strangely announces that “He is a very little fellow, that’s true …” How is it possible, the other asks, that Dupin knew such same words (or thereabouts) were on his mind? Dupin proceeds to methodically reconstruct each of his companions’ tell-tale actions since their prior remarks, which only leads to the conclusion that his friend was indeed pondering this “little fellow” in question.

- Ditto, on their premier meeting, Holmes tells Watson, “You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive,” to which the astonished doctor replies, “How on earth did you know that?” A few days later, Holmes reveals the cogitation that led him to this truth. Knowing but Watson’s occupation, Holmes’ deft powers of observation deduced his conclusion, ala the “links in a chain” that Dupin logically built out of his companion’s actions. Holmes noted Watson’s military posture and bearing (British army), tanned skin (from the sunny tropics?), haggard face (hardship), and lame arm (battle injury?). Where could the good doctor have been? Since British and Indian troops had recently been at war there to counter Russian influence, ergo, Watson must have served in Afghanistan.

- Apart from plot parallels, Dupin is keenly described as a person of “peculiar analytic ability,” one who makes, in silence, “a host of observations and inferences.” Rather than a man of raw physical prowess, Poe’s protagonist delights in the intellect, in disentangling “enigmas, conundrums, and hieroglyphics,” relying on both his intuitive talents as well as a vast reservoir of knowledge tapped from reliable sources, especially scientific observation and reference. For Dupin to crack the case of the Rue Morgue slayings, he will notably draw on his familiarity with the pioneering French zoologist Georges Cuvier’s illustrated The Animal Kingdom (1816). Symmetrically, Holmes hunts for potential clues to solve the “Brixton Mystery” armed with a magnifying glass and, crucially, the seemingly innocuous discovery of a small box of pills at the murder scene.

- For Dupin, Holmes, and a legion of gumshoes to follow, the detective-hero principally acts alone or in concert with a benign second fiddle; our hero (or heroine) invariably cracks the case despite interference or ineptitude on the part of the authorities. Not only do the blundering lawmen often arrest and jail the wrong man, but they also have few kind things to say about the know-it-all amateur sleuth mucking around their crime scenes. In Dupin’s case, the investigating gendarme sarcastically remarks that he should “mind his own business”; as for Holmes, his Scotland Yard counterpart is the “rat-faced” Legarde, utterly conventional but “the pick of a bad lot.”

- Both mysteries are anchored in a singular setting that will, in time, become foundational in the genre: the “sealed room” crime conundrum. On the Rue Morgue, a young woman is discovered brutally slain in her locked-from-inside fourth-floor bedroom, while her mother’s ghastly mutilated remains are found on the grounds below, apparently flung out the window. Yet that window is also found locked—and evidently from the inside. “An insoluble mystery” is the public verdict. But that was before Dupin arrived to “scrutinize everything,” including the victims and that supposedly latched window. In any case, whoever killed the two women was truly a beast.

- Similarly, Holmes and Watson are beckoned to a south London home where a murdered man, an American, lay inside on the dining-room floor. While Legarde and his partner are proven dead wrong in their glib presumptions about the homicide—thrown off by a “red herring” planted by the killer—Holmes methodically examines the entire scene for 20 minutes, irresistibly reminding Watson of a “well-trained foxhound” on the scent. Armed with his own “peculiar analytic ability,” tape measure, and that magnifying glass, Holmes nonchalantly announces his logically deduced findings (“child’s play”), which will undoubtedly lead him to the culprit. And so, as Holmes remarks, “the plot thickens.”

In Edgar Allan Poe’s Footsteps

A Study in Scarlet attracted only pale notices on its release, perhaps unsurprisingly in light of its peculiar 100-page digression that tells the rambling “back-story” of the blood feud between the murderer and his victim that began years before in Mormon Utah, of all places. By the early 1890s, Doyle had ironed out and streamlined his plots, snugly folding most into compact short stories like “The Speckled Band” that would translate the adventures of Holmes and Watson into a best-selling literary phenomenon at home and abroad (though largely to Doyle’s dismay).

In tandem with Poe and other predecessors, Doyle’s legacy in detective fiction looms large even today, whether in plotting or characterization, in books or in film and television. Be it Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple, Raymond Chandler’s hardboiled Philip Marlowe, Hollywood’s comical Inspector Clouseau, or Jessica Fletcher in TV’s Murder, She Wrote, all more or less followed the trail staked out by Edgar Allan Poe, with Arthur Conan Doyle right on his heels.