After the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, Tokugawa Ieyasu was able to eliminate the last major challenge to his bid for the shogunate. As the highest authority in Japan next to the Emperor, Ieyasu ushered in a largely peaceful and stable era that lasted for over two centuries. There was small-scale violence and rebellion by commoners, but the days of endemic warfare had thankfully ended. Samurai who had trained their whole lives and identified and prided themselves as warriors now needed to pursue other occupations.

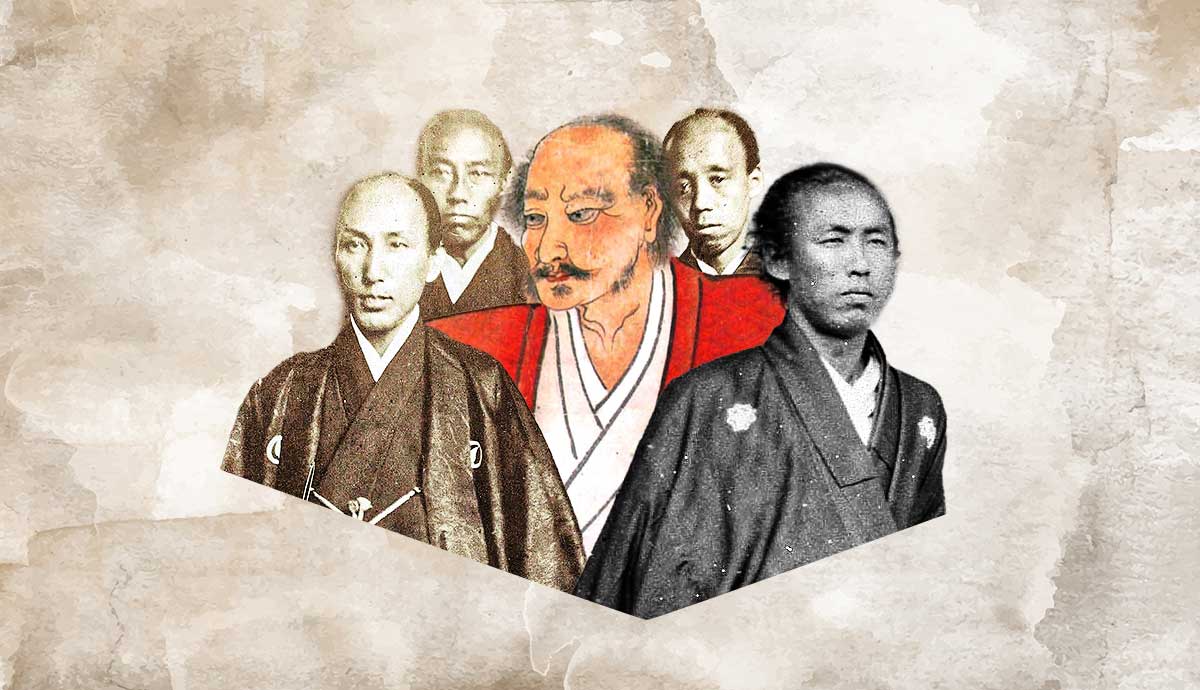

Sakamoto Ryoma, the Tokugawa Reformist

When asked to name one of the founders of modern Japan, one name often comes to mind: Sakamoto Ryoma. He was a samurai who grew up in the Tosa province in the late 1830s. His family was of a lower rank, so they could not progress up the social ladder much under the rigid structure of the shogunate. The Tosa province had fought in the Western Army at Sekigahara and was relegated to a far-flung, poorer domain as a punishment and to prevent the likelihood of future uprisings.

One of the tipping points for the distrust of the shogunate was its perceived weakness in response to Commodore Matthew Perry’s show of force in 1853. This ultimately led to Sakamoto Ryoma helping to usher in the Imperial Restoration.

His first major contribution to the cause was the mediation of the Satcho Alliance between Takamori Saigo of the Satsuma province and Takayoshi Kido of Choshu. Together, they created a naval trade organization named Kamiyama Shachu that aided the alliance in building an independent, modernized navy. The idea was to prevent the subjugation of Japan by foreign forces, because two centuries of isolation had led to widespread technological stagnation, and the recent Opium Wars in China had shown what the West was capable of.

Although no single person can be credited with the modernization of Japan, Sakamoto Ryoma played an undeniable part. Were it not for his efforts, the Satcho Alliance and the creation of Japanese naval power might not have occurred.

Hasekura Tsunenaga, the Religious Ambassador

Hasekura Tsunenaga was a retainer of the daimyo Date Masamune of the Mutsu province. Date was known for his enthusiasm toward Western culture and used this attribute in the service of the Tokugawa regime. At the time, Spain dominated the seas in Southeast Asia, and Tokugawa wanted to enter diplomatic and trade relations with Spain for even greater wealth.

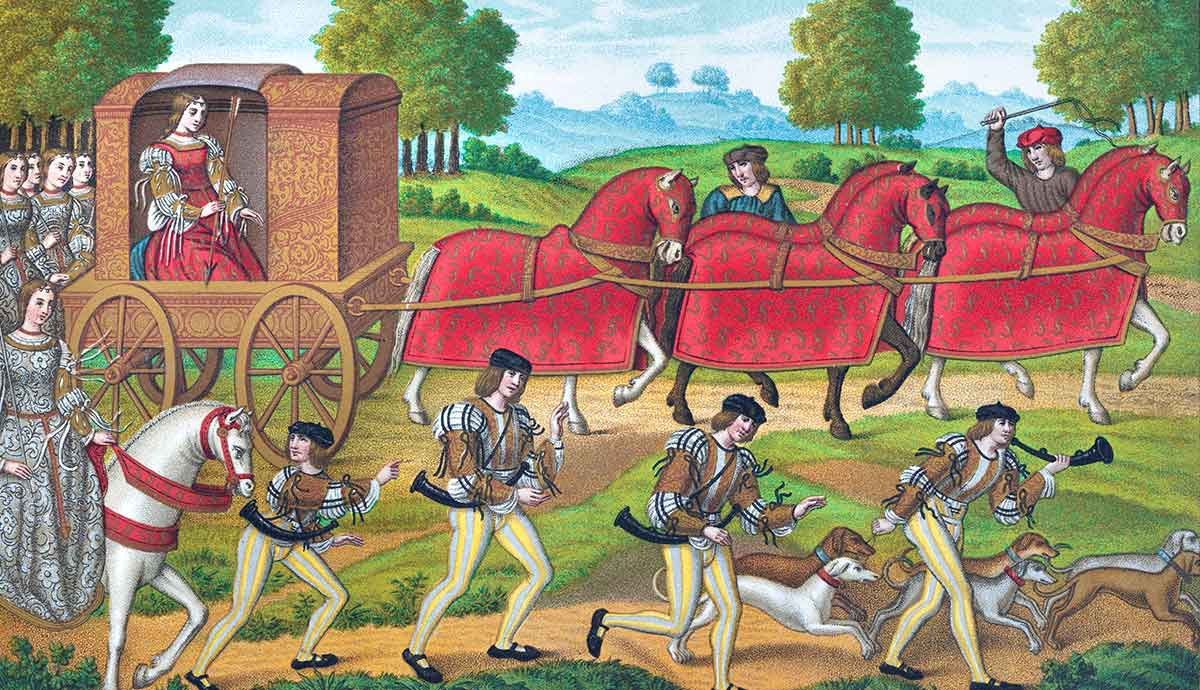

Tsunenaga’s father, Tsunenari, came under charges of corruption and conspiracy and was executed. In this situation, normally, the transgressor’s entire family would be put to death as well, but Date Masamune gave Hasekura a chance to restore his honor. Hasekura took the position of leader for the Keicho Embassy, containing 180 people. The group departed Japan in 1613, landing in Mexico, where the embassy received a warm welcome and cemented the beginning of ties between Mexico and Japan.

After a short stay in Mexico, the Keicho delegation sailed across the Atlantic, landing in Spain and securing a trade deal with King Philip III. Then they traveled to Rome, where Pope Paul V received Hasekura Tsunenaga and was so pleased by the Japanese response to Christianity that he soon named Tsunenaga an honorary Roman citizen, and also agreed to send missionaries to Japan to teach Catholicism.

Unfortunately, Tsunenaga came back to a Japan that had, under Tokugawa Hidetada, taken a much more exclusive stance toward foreign influence: European trade had been restricted to Dejima, a man-made island off Nagasaki. Christianity had largely been repressed on penalty of death or exile. Although Tsunenaga’s efforts did not initially bear fruit, they made a favorable impression on the West.

Miyamoto Musashi, the Sword Saint

Miyamoto Musashi, born Miyamoto Bennosuke of Harima province, hardly needs an introduction. Anyone familiar with Japanese history has likely heard his name in connection with winning numerous duels in the pursuit of perfecting his swordsmanship.

Musashi often receives credit for creating a fighting style that used the katana and wakizashi together, but he was not the first person to come up with this idea. As a swordsman, Musashi was known for his unorthodox approach to fighting and disdain for the conventions of duels. He wrote about this in his treatise Go Rin no Sho (The Book of Five Rings). In the book, Musashi advocated for a fluid approach to fighting and advised warriors not to have a favorite weapon, among other things.

Musashi’s text serves as versatile advice centuries after his death to people from all walks of life. The Ground Book lists the qualities of being honest with oneself, consistency in effort, efficiency, and a broad knowledge base. The Water Book advises flexibility in both body and mind, and to never go completely still. The Fire Book teaches that one should consider the environment to act most effectively; in a modern business context, that could mean learning about the market conditions, for example. Wind and Void, meanwhile, are more philosophical and analyze weaknesses in others based upon experience.

A week before he died in 1645, Musashi wrote a short text titled Dokkodo (The Way of Aloneness), as a dedication to his student Terao Magonjo. It was a series of precepts by which to live a focused, fulfilled life. They echo many Buddhist teachings, such as holding no permanent attachments, asceticism, and acceptance of reality without holding onto any desire.

Yamamoto Tsunetomo, the Warrior-Philosopher

Most of the modern understanding of Edo-period bushido comes from a book called Hagakure, compiled by an 18th-century samurai named Yamamoto Tsunetomo, although the actual author of the book was Tashiro Tsuramoto. Tsunetomo served as a low-ranking retainer for Nabeshima Mitsushige, a daimyo of Hizen province, but did not get a distinguished position. Despite this, Tsunetomo remained loyal—loyal to the point that he requested permission to commit seppuku upon Nabeshima’s death.

This practice, known as junshi, had been outlawed, though many samurai practiced it anyway. Tsunetomo then began working on Hagakure. The name translates to Hidden Leaves, which can allude to either the fact that the book was never meant to be read or the lamentation of the supposed decline of the samurai warrior spirit. One of the most well-known parts of the book advocates daily meditation upon one’s own death as a means of overcoming fear of it in order to live life to the fullest. This is a noble goal, though with a morbid and sobering process. Unlike Go Rin no Sho, Hagakure is not organized in any way; it is simply a collection of thoughts and ideas that Tsunetomo wrote, based on traditional advice.

Tsunetomo’s work had a dark influence. The concepts of absolute loyalty, fearlessness in the face of death became part of nationalist war propaganda. It fueled some of the worst atrocities the Japanese military committed before and during World War II, which the Japanese government has still not acknowledged.

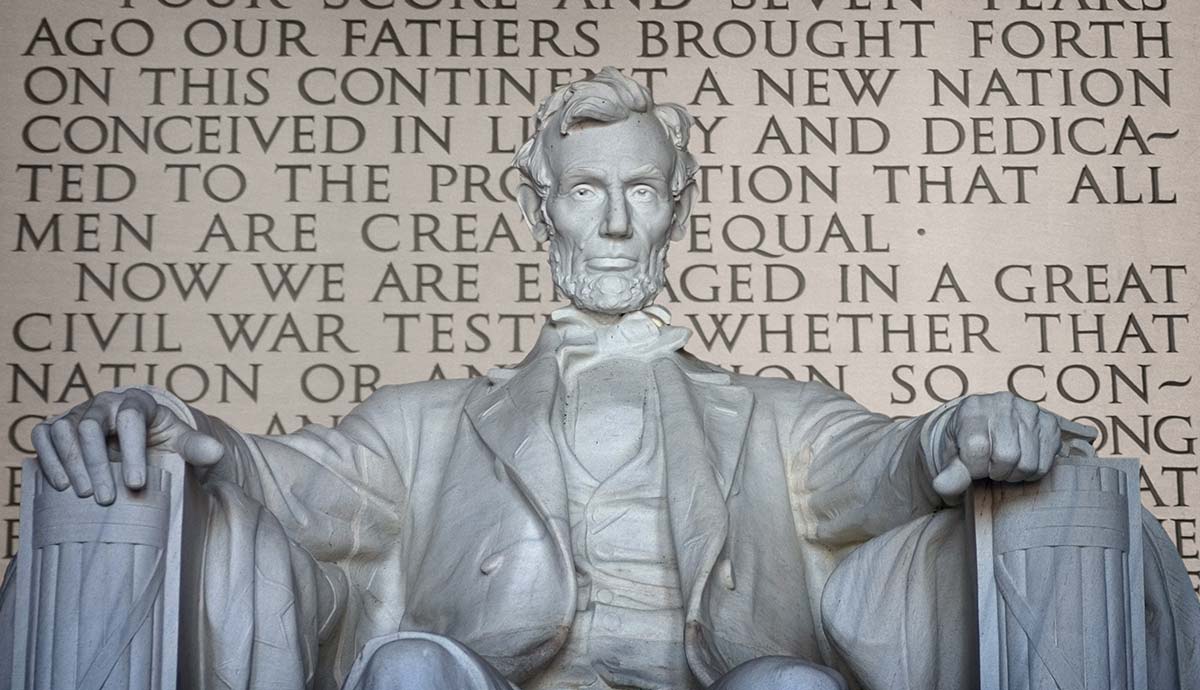

Shinmi Masaoki, the Modern Diplomat

In 1853, when Commodore Perry forced Japan to open its ports to America, the Tokugawa shogunate witnessed the comparatively vast military power of the United States and capitulated, not wanting Japan to suffer the same fate as China had during the Opium Wars. After the signing of the Treaty of Amity and Commerce, the shogunate appointed Shinmi Masaoki to lead the first Japanese embassy to the West since Hasekura Tsunenaga’s journey to Rome two centuries prior. He traveled to Washington, D.C., stopping in San Francisco and New York as well after passing through Panama.

Shinmi Masaoki met with President James Buchanan, presenting him with a copy of the treaty, beginning cultural exchange between the United States and Japan. Descriptions by onlookers express marvel at the exotic appearance of the Japanese, especially because they wore their swords and the traditional samurai garb.

Furthermore, the embassy’s aim was to demonstrate to the world that the Japanese had begun to develop a modern navy. The Kanren Maru was one of Japan’s first modern steam-driven warships.

William Adams, the Navigator

William Adams was the first Englishman to land in Japan, and his story is well-known thanks to James Clavell’s bestselling novel Shogun. He was born in Kent and spent his early life learning the craft of shipbuilding and sailing. Adams worked for a predecessor of the Dutch East India Company; his expedition sailed out of Rotterdam in the Netherlands, landed in Japan in 1600 on the Liefde, the only surviving ship of the five that started out.

Tokugawa Ieyasu interviewed Adams, learned what he could of the relations between England and other European nations, recognized him as an asset to the government, and made him a retainer whose task was to train the army in the use of artillery. In 1605, Adams was granted the title of hatamoto, a direct vassal, for his services. William Adams helped to bolster Edo-era Japan’s naval forces, building some of the first Western-style ships that carried samurai such as Hasekura Tsunenaga on voyages around the world.