Was Eileithyia her own goddess or just another aspect of Hera? The answer isn’t a straightforward this-or-that. In some regions, Eileithyia was worshiped as a distinct deity of childbirth, with ancient sanctuaries dedicated to her alone. Elsewhere, she is depicted as Hera Eileithyia, one of the many masks worn by the queen of Olympus. The fluid nature of Greek polytheism allowed for shifting identities in which a god or goddess could be both separate and the same, depending on who was telling the story. From Crete to Argos, from Homeric hymns to cultic rituals, Eileithyia’s identity dances between independence and a strong reliance on both Hera and Artemis, revealing the lack of rigidity in ancient belief (and the differences that could crop up before the internet made sharing ideas easy on a global scale).

Worshiping Hera in Childbirth

Hera’s role as a goddess of marriage naturally extended to childbirth—at least for women who were legally and honorably married. As the faithful wife of Zeus, Hera was often invoked by expectant mothers who sought a safe delivery and healthy children. Women who were trying to conceive also prayed to Hera for fertility, hoping the goddess of marriage would bless them with offspring to secure their family’s future.

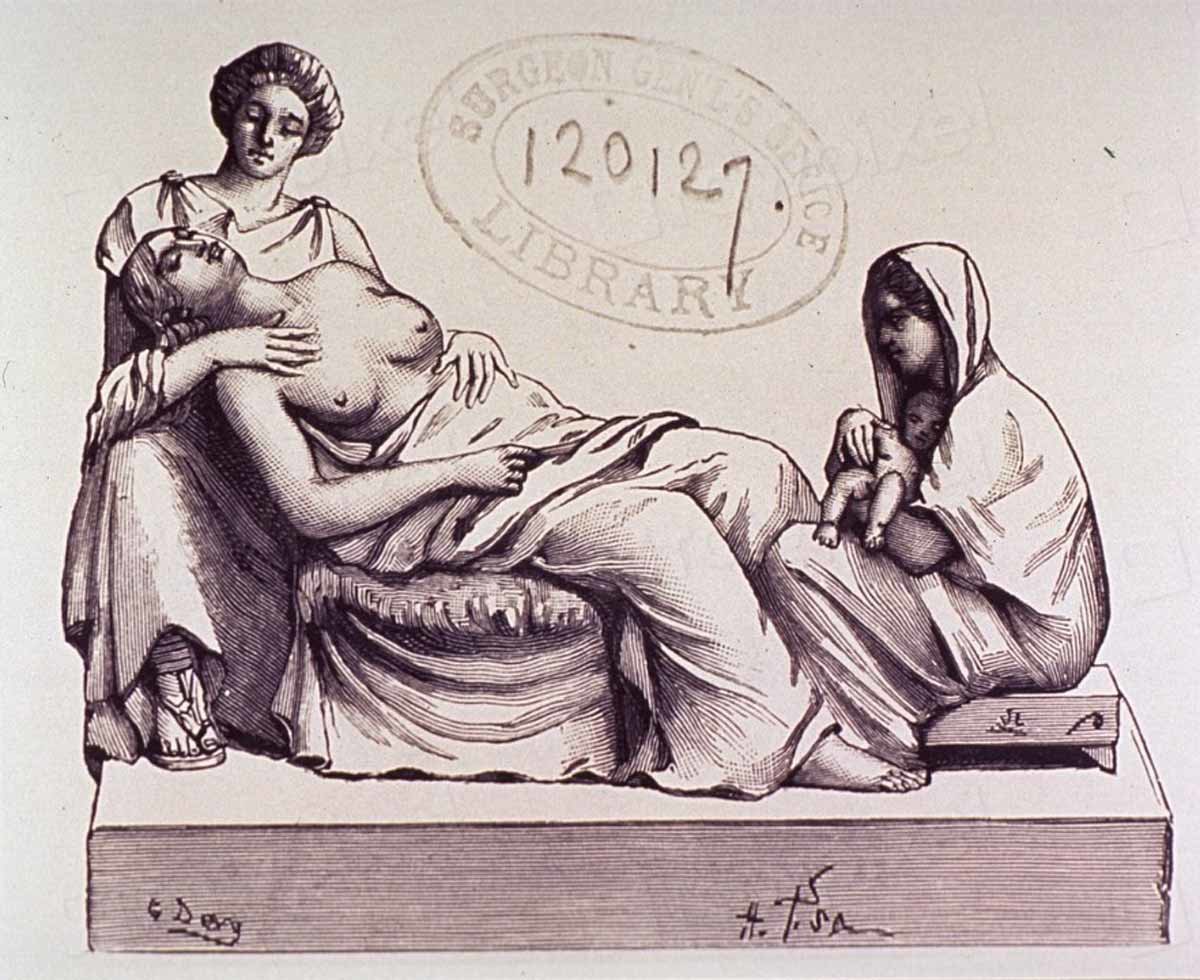

In cities like Argos, Samos, and Corinth, grand temples dedicated to Hera (called Heraia) stood as places of pilgrimage where women would lay offerings in hopes of winning their holy queen’s favor. Archaeological excavations at Hera’s sanctuary in Argos have revealed small terracotta models, either bought or made locally, that serve as clear evidence that ancient women turned to her during their journeys to and within motherhood.

There’s evidence that apples became symbolic of Hera’s power over fertility. According to myth, when Hera married Zeus, Gaia (aka Mother Earth) presented the couple with an apple tree as a wedding gift. The apples, blessed to grant eternal youth and fertility, were a reminder of Hera’s role as a life-giver and faithful mother to the next generation. Over time, the apple tree became inseparable from Hera’s core mythology. This is why, in some regions, women hoping to conceive would offer apples or other fruits that bore several seeds, like pomegranates (again, a nod to Hera’s fertility in marriage), at her altars as a symbol of their desire for a house full of children. The fruit’s association with fertility and divine favor persisted, reinforcing Hera’s role as a patroness of conception and childbirth.

Yet Hera’s power over childbirth could be both beneficial and a deterrent to poor behavior. As the long-suffering wife of philandering Zeus, Hera had a complicated relationship with the birth of his illegitimate offspring and the women who had to bear them. While she was invoked to protect most mortal women in labor, Hera also wielded her power as a weapon against Zeus’s lovers and their children.

One of the most famous examples was the birth of Heracles, Zeus’s son with the mortal Alcmene. Furious at another of the god’s affairs, Hera both delayed Heracles’s birth while speeding the labor of another male child, Eurystheus, ensuring that he—not Heracles—would become king of Mycenae. In another myth, she prevented Leto, Zeus’s lover, from giving birth to the twin gods Apollo and Artemis by blocking her access to any land where she could deliver safely. Imagine being in the midst of labor with two godly children but having no relief in sight.

This duality—nurturer of legitimate births and antagonist of illegitimate ones—reflected Hera’s deep entanglement with the social and marital order of ancient Greece. Women who fell within the bounds of respectable marriage sought her aid, while those who operated free of it often found themselves outside of her benevolent purview. Whether through protection or punishment, Hera’s influence over childbirth was undeniable, and women across the ancient world turned to her, hoping she would smile upon them—or, at the very least, not turn her anger in their direction.

Worshiping Eileithyia in Childbirth

If Hera was the queen of marriage, Eileithyia was the hands-on-deck goddess of labor and delivery. No fanfare, no golden chariots—just raw, screaming childbirth. Where Hera watched over the social order of marriage, Eileithyia handled the messy, bloody business of getting babies from womb to world. It was indeed a gory business because, let’s be clear, ancient childbirth wasn’t exactly the cozy, medicated affair of modern luxury maternity wards. It was life or death, and if you were an ancient Greek woman in labor, you’d be calling on Eileithyia like your life depended on it (because it probably did).

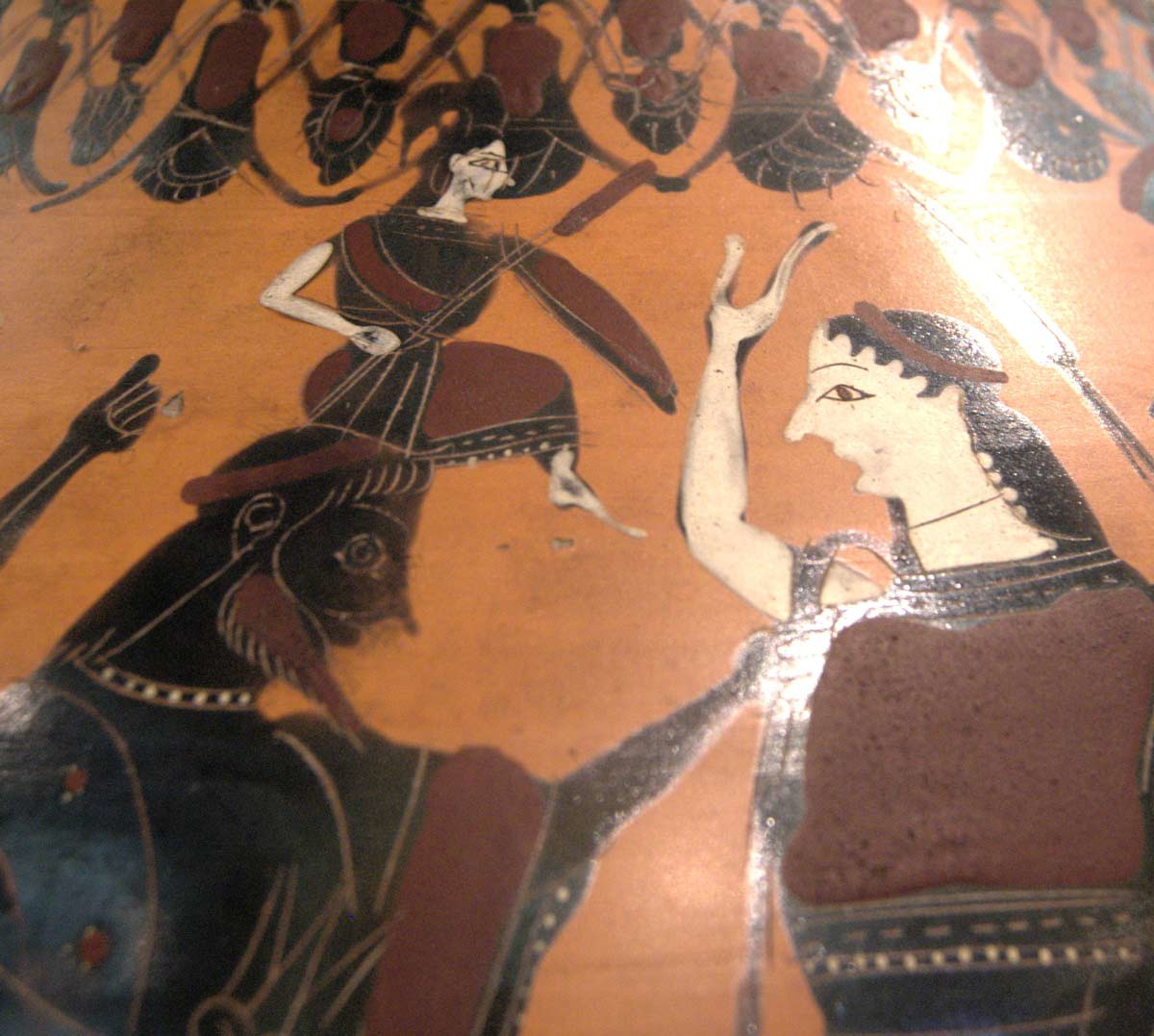

Eileithyia’s temples were less about grand, showy worship and more about pleas of desperation via offerings and fervent prayers. Women didn’t invoke her for ideal birth experiences; they just wanted to survive and see their children make it through as well. In places like Amnisos on Crete and Olympia, archaeologists have found evidence of her cult dating back to the Bronze Age—proving she was worshiped here long before Hera made the trip across the water. Pregnant women or their families would offer small figurines of babies or swaddled infants, sometimes carved in stone, sometimes shaped by hand in clay, hoping Eileithyia would take the hint and bestow some blessings.

It might be mind-blowing to the modern doctor or patient, but Eileithyia wasn’t the goddess of safe, easy births (because who wouldn’t want one of those?!). She was the goddess of labor itself. Her presence didn’t promise smooth deliveries or pain-free experiences—she was the pain. Her name literally means “she who comes to bring the child” (and she didn’t do it gently). If labor dragged on, it was said that Eileithyia was being withheld—either by Hera or by some other divine grudge. When things got dicey, people would frantically offer more gifts or sacrifices to coax her into making an appearance. Think of it like trying to nudge the world’s most indifferent midwife: Please, ma’am, I’m begging you. Do something. Or, perhaps it’d be more like using prayers as a sort of ancient Pitocin. We can guess that they weren’t anywhere near as effective.

There’s a story where Hera actually did withhold Eileithyia. When Zeus’s lover, Leto, went into labor with the godly twins Apollo and Artemis, Hera was so livid she physically restrained Eileithyia to keep Leto from giving birth. Poor Leto had to squat in excruciating pain for nine days and nights until the other goddesses intervened and freed Eileithyia from Hera’s clutches. It was weaponized childbirth, and it didn’t hurt the person who Hera was actually upset with (Zeus, the man who seemed perpetually unable to keep it in his marriage) at all. Instead, it was punishment by a goddess for a goddess.

Despite her somewhat sinister vibe (because, really, what expecting woman isn’t somewhat afraid of giving birth?), Eileithyia kept her role as the ultimate judge when it came to birth. Whether she was answering prayers or flat out ignoring them, she was the one who held the strings. Perhaps this is why, in many stories, she remains so close to the Morai—the Fates. Hera might have had the temple-dedication crowd, but when it came time for the real work—the blood, the screaming, the dangerous, tear-you-in-half ordeal of labor—it was Eileithyia women really wanted on their side… assuming she was in the mood to help.

So Who Was Eileithyia?

Was Eileithyia an avatar of childbirth, bringer of pain, midwife of the gods, or perhaps just Hera in another hat? Maybe she was Hera’s daughter? Is it even possible the answer could be yes to all? The ancient Greeks never made this clear, and scholars have been pulling their hair out over it ever since. However, the basic fact of the problem is that it is probably infinitely more important a sticking point to us than it was ever to those that actually worshiped her/them. The Greeks were quite aware that their gods appeared differently in different places, with the biggest reaction being an ancient shoulder shrug. Depending on which Greek city-state you were in, Eileithyia was either her own powerful deity or just another face of Hera or sometimes Artemis. If you asked a priest in one city and a priestess in another, you’d probably get two very different answers.

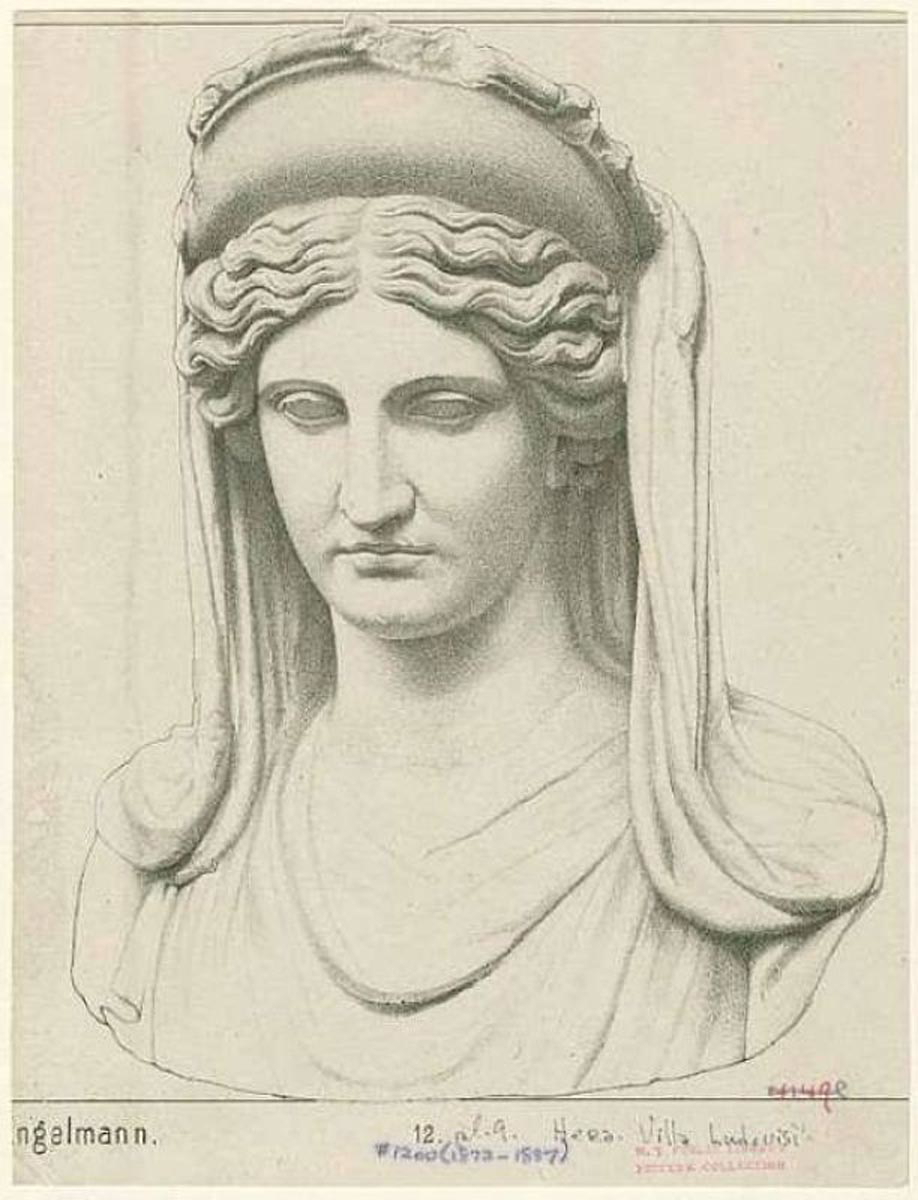

Let’s start with the very word itself. Eileithyia wasn’t so much a personal name as it was an epithet—a fancy poetic nickname used to highlight a particular aspect of a god’s power. Hera, famous for this, collected epithets like they were going out of style. You had Hera Gamelia (Hera of Marriage), Hera Argeia (Hera of Argos), Hera Basileia (Hera the Queen), Hera Teleia (Hera of Fulfillment)—the list is fantastically long. So when ancient Greeks referred to Hera Eileithyia, they were essentially invoking “Hera the Childbringer,” as if she easily swapped a crown and the finest linens for scrubs when labor day rolled around.

Somehow, it gets messier. In certain places, Eileithyia was considered an entirely separate goddess, complete with her own temples and rituals. Archaeological digs at Amnisos and Olympia have uncovered temples to her, ones seemingly visited exclusively by pregnant women hoping to avoid tragedy in labor and delivery.

There was the whole daughter of Hera angle. Some myths, particularly the later ones, insist that Eileithyia was Hera’s actual child—born and bred from the queen of the gods and Zeus. It does make a roundabout, weird kind of sense—the goddess of marriage and childbirth might as well make her own daughter the official midwife of Olympus, the girl herself living proof of Hera’s grip over matrimony and conception.

Keeping these various original stories in mind, there’s also the distinct possibility that Eileithyia was never intended to be Hera’s daughter and that the whole family tree mess was a later invention to explain why their domains overlapped. Think of it as an ancient rewrite to better tell a tale that’s been added to by too many authors and desperately needs a streamline.

Then—more confusion—there’s Artemis. Yes, that Artemis: virgin goddess of the hunt, sworn enemy of marriage, and all-around girl boss of the wilderness. Despite her “no men, no marriage, no babies” policy, Artemis was frequently given dominion over childbirth. It mainly comes down to her being born without complications, while her twin brother Apollo got stuck in the birthing canal. Artemis took that personally and vowed to protect women in childbirth since boys were so troublesome. Naturally, this brought her into direct association with Eileithyia since both deities were invoked in labor. In fact, some regions merged them entirely, especially in places like Delos, where both Artemis and Eileithyia were honored in childbirth rituals.

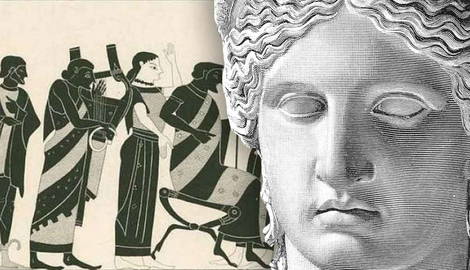

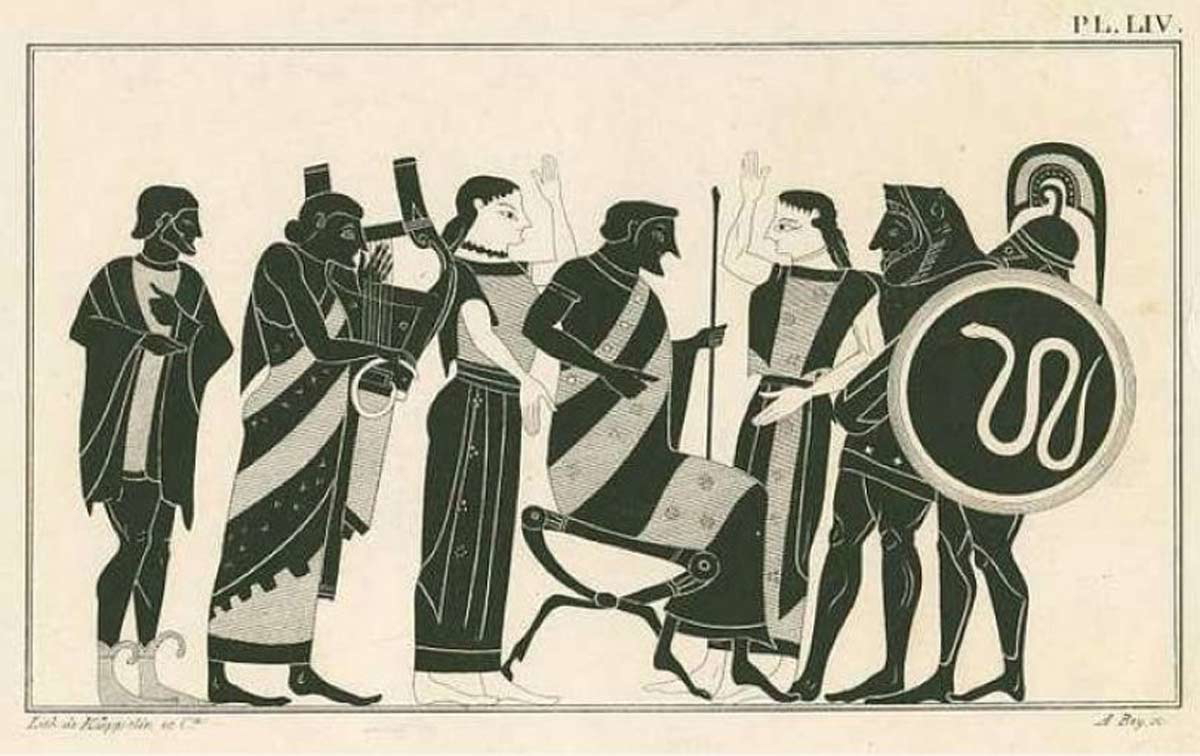

It is somewhat of a theological train wreck: Eileithyia was her own goddess, Hera’s alternate form, Hera’s daughter, and also Artemis’s partner in midwifery. The archaeological evidence doesn’t make things clearer. There is a famous 6th-century BCE kylix (drinking cup) from Athens that depicts Eileithyia assisting in Athena’s birth from Zeus’s skull and labeled specifically as Eileithyia, not Hera. However, at Hera’s temples in places like Argos and Samos, archeologists have discovered inscriptions calling her Hera Eileithyia with just as much clarity.

So, what’s the final answer? Honestly, it depends on where you were standing in ancient Greece. If you were in Crete, Eileithyia was probably her own independent deity and a primal force of labor and pain. If you were in Argos or Athens, she was more of a function of Hera—a bit of a job title, not a separate entity. If you were in Delos, you’d probably shrug and say, Eh, she works with Artemis now.

Generally, the ancient Greeks were fine with that inconsistency. Gods didn’t have to fit into neat categories or have clear genealogies—they were vast, contradictory, and complex, much like life. Really, whether Eileithyia was her own goddess, Hera in disguise, or a reluctant midwife to both goddesses and mortals alike, one thing was clear: if you were in labor, you were begging someone, anyone to get her there—fast.