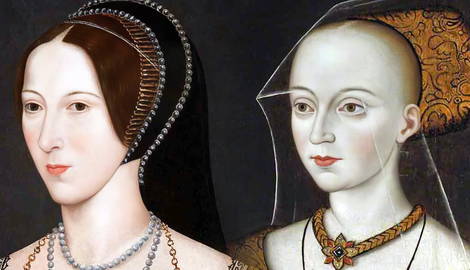

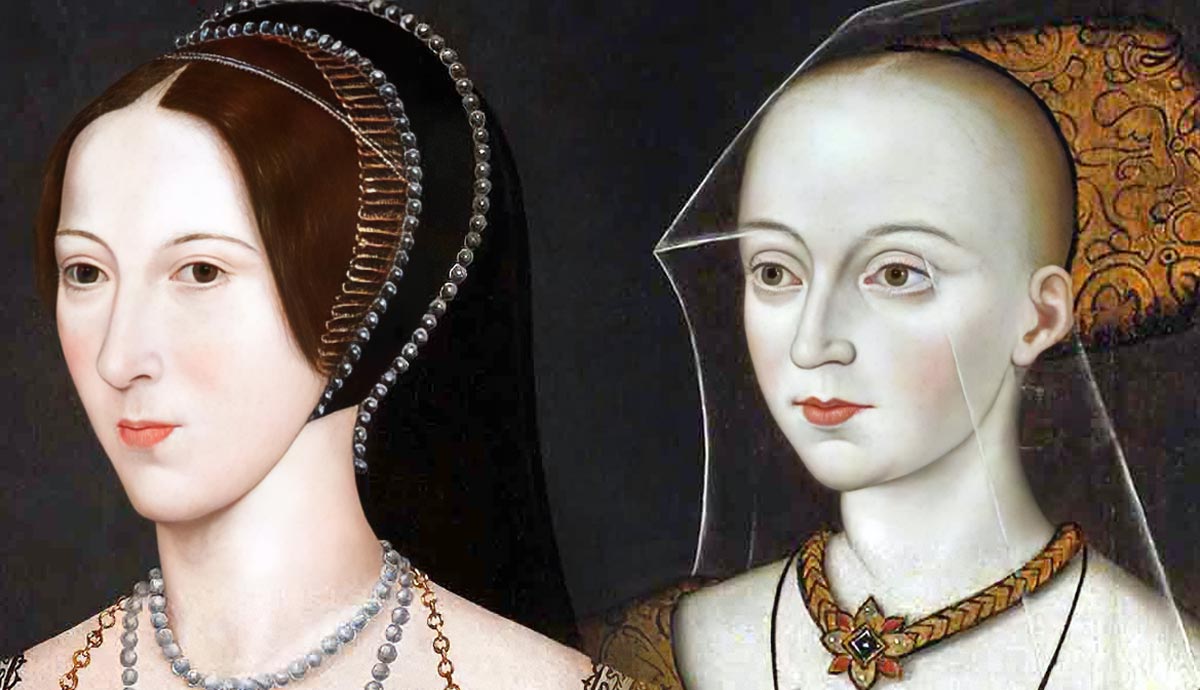

Elizabeth Woodville and Anne Boleyn had more in common than just their indecent (by the rules of their time) royal marriages. Both women were legendary for their mix of wit and elegance—and for the political tremors their unions caused. Perhaps, what stands out most is that these two women, unlike many of their contemporaries, refused to be labeled “mistress.” Where others may have submitted to powerful kings who were accustomed to yes-men and women, Elizabeth and Anne drew bold lines and made audacious demands, each in her own right. For this, they were both exalted and maligned, and in many ways, their lives illustrate the peculiar hazards that awaited any woman who dared to insist on living her life with agency.

1. They Both Had Loved Before

Both Elizabeth Woodville and Anne Boleyn entered their iconic royal entanglements with notable romantic encounters behind them. Elizabeth had been married and widowed before she laid eyes on Edward, and Anne had considered betrothal to two men—though neither proposal ended in wedding bells—before Henry made his intentions known.

Elizabeth Woodville was already a young widow when she met Edward IV, England’s most eligible bachelor-king. Her first husband, Sir John Grey of Groby, wasn’t just any knight; he was politically tied to the Lancastrian cause, a fact that would eventually cause trouble. Elizabeth’s life with John was, by all accounts, respectable and steady—until the Wars of the Roses ended his life and left Elizabeth a young woman caring for two nobly born children.

Did Elizabeth resign herself to an uneventful widowhood? Not quite. Instead, she used her uncommon beauty and knack for persuasion to move up the social ladder, ultimately putting herself on Edward’s radar. She placed herself beneath an oak tree beside a road she knew the king was due to pass by, arranged herself in the best light, and then, not knowing her actions were about to change English history, she waited.

Now, let’s switch to Anne Boleyn, who was also no stranger to the court’s matchmaking carousel. Before Henry VIII and his dangerous theatrics, but after the Butler intrigue, Anne was actually setting herself up for a love match with none other than Henry Percy, the future Earl of Northumberland. It was the kind of young romance that court ladies whispered about—except that this was the Tudor court, so the whispers quickly became loud opinions from folks like Cardinal Wolsey. This rather influential clergyman stopped the Anne/Percy match faster than you could say “papal displeasure.” Wolsey, supposedly at Henry VIII’s nudging, declared the engagement invalid and inappropriate due to the difference in the lovebirds’ aristocratic status. Percy was sent away, and Anne’s future became spoken for, whether or not that’s what she truly wanted.

Anne first returned to England from France in 1522, rumored to be engaged to James Butler, the 9th Earl of Ormond, in an arrangement meant to settle a long-standing family feud over land and title claims. But the match was canceled, whether because of Anne’s ambitions, court politics, or simply fate—we can only speculate. Instead of becoming a countess, Anne took on the prestigious position of maid of honor to Queen Catherine of Aragon. From there, her path to fame (or, more accurately, infamy) began. It wasn’t long before her charm and wit caught the eye of a certain King Henry VIII, who was on the prowl for the kind of woman who could give him a son.

2. They Refused to Be Royal Mistresses

When Edward IV first approached Elizabeth Woodville with his interest in taking her to bed, she was very clear on her refusal to become his mistress. According to rumor, she didn’t merely reject him: she also made a rather dramatic promise, reportedly threatening to take a knife to her own throat before being seduced into such a position.

Elizabeth wasn’t interested in a royal affair—she was looking for a title, status, and a secure future for herself and her two sons from her previous marriage. Whether or not the knife threat was an apocryphal invention, Edward was deeply impressed with Elizabeth’s steadfast values. Instead of forcing his hand, the new king proposed and then swiftly married the young widow in secret. Elizabeth entered that marriage bringing her young boys into the royal fold, setting a strong foundation for her family’s future prospects.

Anne Boleyn, on the other hand, tried a different escape strategy when she caught Henry VIII’s eye. Anne packed her things and returned to Hever Castle, trying to put distance between herself and the amorous king. For a while, her “no” stuck, as she eluded Henry’s courtly pursuit and his increasingly ardent letters.

It wasn’t until almost a year into his love-bombing, around January of 1527, that Anne finally agreed to marriage—though not without a significant condition. Henry’s letters and their timing suggest that Anne may have finally accepted his hand in early January, with the symbolic offering of her “étrenne,” or virginity, signaling her commitment. By 1533, Anne had fully secured her place as Henry’s queen, though it had taken several years of fraught and cautious negotiations on her part.

Neither Elizabeth nor Anne stepped into a royal romance without a plan or purpose. Both women, with sharp wit and nerve, demanded legitimacy for themselves and their families. Both would use their new positions of power to take great care of their extended families, with Elizabeth providing for her sons within her new royal household, and Anne later supporting her young nephew Henry Carey, using her purse to fund his education.

For these two formidable queens, the throne was more than a badge of womanly success—it was a hard-won symbol of their initial defiance, a new status achieved on their own terms.

3. Both Marriages Produced History-Making Elizabeths

For all their boldness, political intelligence, and resilience, Anne Boleyn and Elizabeth Woodville also left legacies in the form of two of Tudor history’s most influential women: Elizabeth I and Elizabeth of York. Both of these Elizabeths carried their mothers’ tenacity and resilience into new eras, shaping the way the people would come to see women and their place in the world.

Anne Boleyn’s daughter, Elizabeth I, was famously never supposed to inherit the throne. She was, after all, labeled an illegitimate bastard after her mother’s much-written-about fall from grace. Yet, this maligned princess rose to become one of England’s most powerful sovereigns. Elizabeth went on to defy expectations by refusing to marry, maintaining her autonomy as “the Virgin Queen,” and establishing herself as “Gloriana.” She reigned over a golden age of exploration, art, and relative stability, with her name forever linked to England’s cultural renaissance.

In Elizabeth, Anne’s own indestructible spirit and savvy politicking seemed to live on. Though Anne’s queenship was cut brutally short, her legacy thrived through her daughter, who expertly navigated power dynamics and retained the throne for four and half decades. Elizabeth’s reign was, in many ways, a realization of Anne’s ambitions, an embodiment of the fierce independence and penchant for reform that had marked her mother’s life.

On the other hand, Elizabeth Woodville’s marriage to Edward IV produced a whopping ten more children (wouldn’t Anne’s scheming husband, Henry VIII, be jealous), who became integral to the English royal bloodline. Among them was Elizabeth of York, whose marriage to Henry Tudor—the future Henry VII—helped end the bloodshed of the Wars of the Roses by uniting the warring houses of Lancaster and York. This union not only brought peace to England but also established the Tudor Dynasty, which would last more than a century.

Elizabeth of York, much like her mother, was a woman of charm, intelligence, and political maneuverability. By forging a new royal lineage through her children, Elizabeth would put one daughter on the throne as queen of France, another as queen of Scots, and her son, Henry VIII, as the English monarch.

4. The Treasures They Lost in the Tower

For both Anne Boleyn and Elizabeth Woodville, the Tower of London transformed from a symbol of crown and country to one of profound loss. Anne, who had once stayed there before her coronation, returned years later, only this time as a condemned criminal. The same Tower that had represented her dazzling rise to queenship now became her prison as she awaited trial and execution.

Even in the face of mounting charges, Anne maintained some hope that Henry VIII would show mercy, possibly allowing her to live out her days in an abbey. Unfortunately for her, mercy never came. Instead, a skilled French swordsman was summoned for her beheading, a final twist that perhaps Henry intended as a macabre kindness. Anne’s life, which had once shone so brightly, was extinguished in the very place that had crowned her.

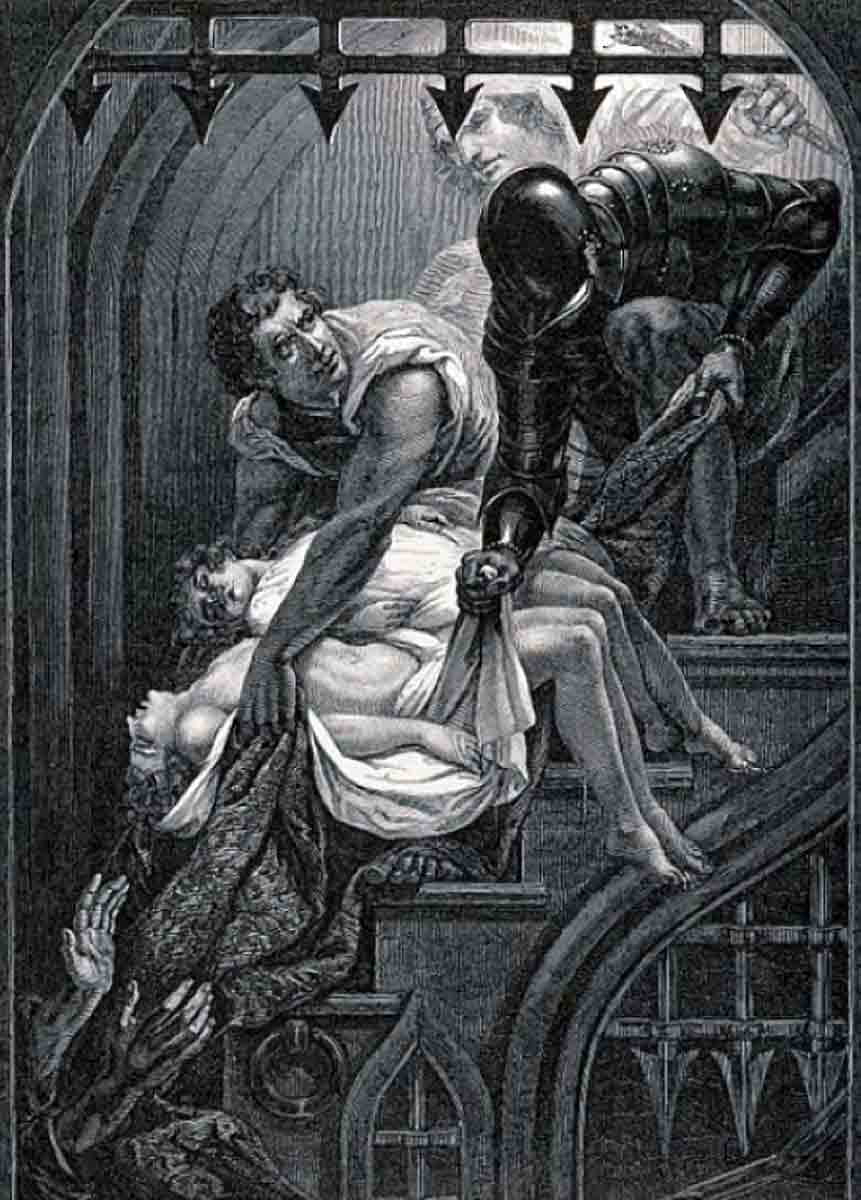

Elizabeth Woodville, too, faced devastation within those ancient walls, though her loss was not of her own life but of her beloved sons. After her husband, Edward IV, passed, Elizabeth’s sons were sent to the Tower, ostensibly to prepare for the young Edward V’s coronation. However, Elizabeth’s brother-in-law, Richard III, moved swiftly against them. He declared the boys illegitimate and confined them in the Tower, where they soon vanished, sparking centuries of mystery over their fate.

Elizabeth, reeling from the loss of her boys, was forced to confront the ultimate betrayal from within her own family. It was this unthinkable loss that would lead Elizabeth down the road to supporting Henry Tudor, aligning their houses with a marriage between him and her daughter, Elizabeth of York, to end Richard’s hold on the throne.

Elizabeth, like Anne, endured her own imprisonment in the Tower but was able to escape with her head. Even after securing sanctuary multiple times at Westminster Abbey during the Wars of the Roses, she could not shield her sons from their fate. Each woman’s heart entered the Tower crowned in hope and left it in unimaginable sorrow. For Anne and Elizabeth, the Tower was the stage on which their greatest losses played out—treasures they could never reclaim, taken by the ambitions and cruelty of callous men.

5. They Were Both Accused of Being Witches

Both Anne Boleyn and Elizabeth Woodville faced politically motivated accusations of witchcraft, tied to the seemingly supernatural allure they wielded over powerful kings. Elizabeth’s reputation as a supposed witch emerged early in her relationship with Edward IV. As a lower-born widow, Elizabeth wasn’t a conventional match for a king, and Edward’s court was shocked by his willingness to ignore every counsel to take her as his queen. He had been expected to pursue a wealthy and advantageous marriage, yet he was utterly captivated by Elizabeth, resulting in him abandoning strategic considerations.

As if her beauty and poise weren’t enough, whispers claimed she must have bewitched him—a trope that stuck with her in historical lore and, likely, helped fuel skepticism about her sons’ legitimacy later on. This same skepticism is what allowed Elizabeth’s boys to be legitimized and imprisoned. Rumors, after all, always have their consequences.

Anne’s case was more insidious and personal, emerging when her reputation was most vulnerable. Henry VIII’s passion for Anne had upended his kingdom, sparking a reformation and a rift with the Catholic Church. As his affections waned, those same courtiers who had once cheered her meteoric rise began whispering that she must have used dark forces to enchant the king. Henry’s resolve to discard her added weight to the trumped-up claim that she was, in fact, no ordinary woman. Only a seductress with “charms” unnatural enough to be considered sorcery could cause so much chaos for a king’s court. Accusations emerged of Anne possessing extra fingers and “marks” that served as evidence of her supposed devilry.

For both queens, rumors of witchcraft served as convenient explanations for how a mere woman could wield such unusual influence over a king. Anne and Elizabeth defied the typical paths of royal wives, proving alluring enough to provoke men to dismantle alliances, traditions, and, in Anne’s case, even a marriage with foreign ties. The witchcraft accusations may reveal more about their accusers than about either woman, underscoring the perceived threat that intelligent, ambitious women posed to the power structures of their day and men who refused to share a modicum of governance.