For centuries, embroidery existed as a decorative practice mostly attributed to women. It had symbolic and religious purposes but was never elevated to the domain of serious art. It all started to change in the 20th century when women artists embraced embroidery as a medium of protest and identity expression. Read on to learn more about the history of embroidery in art.

The Origins and Meanings of Embroidery

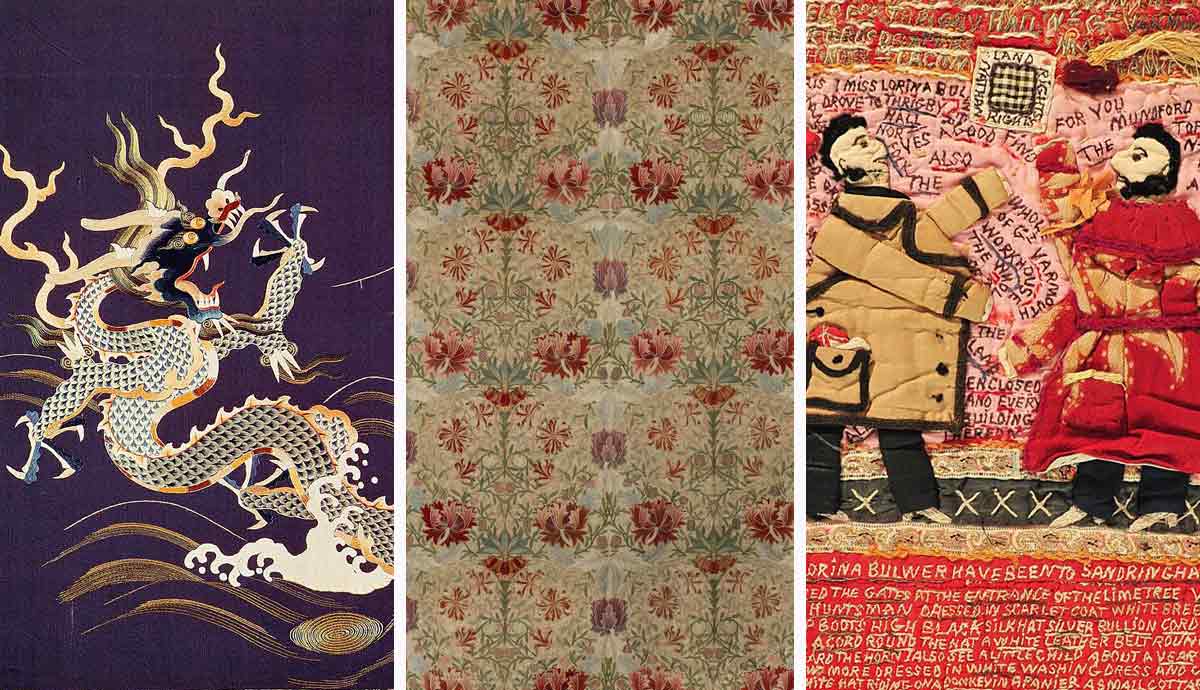

As a practice, embroidery emerged soon after humans learned to stitch two pieces of hide together. Still, it took them some time to begin using it for decorative purposes. Despite the difference in styles, subjects, and materials used, embroidery is a practice that is present in the majority of global cultures. Some of the earliest preserved embroidery works in China date back to the 5th-3rd centuries BCE.

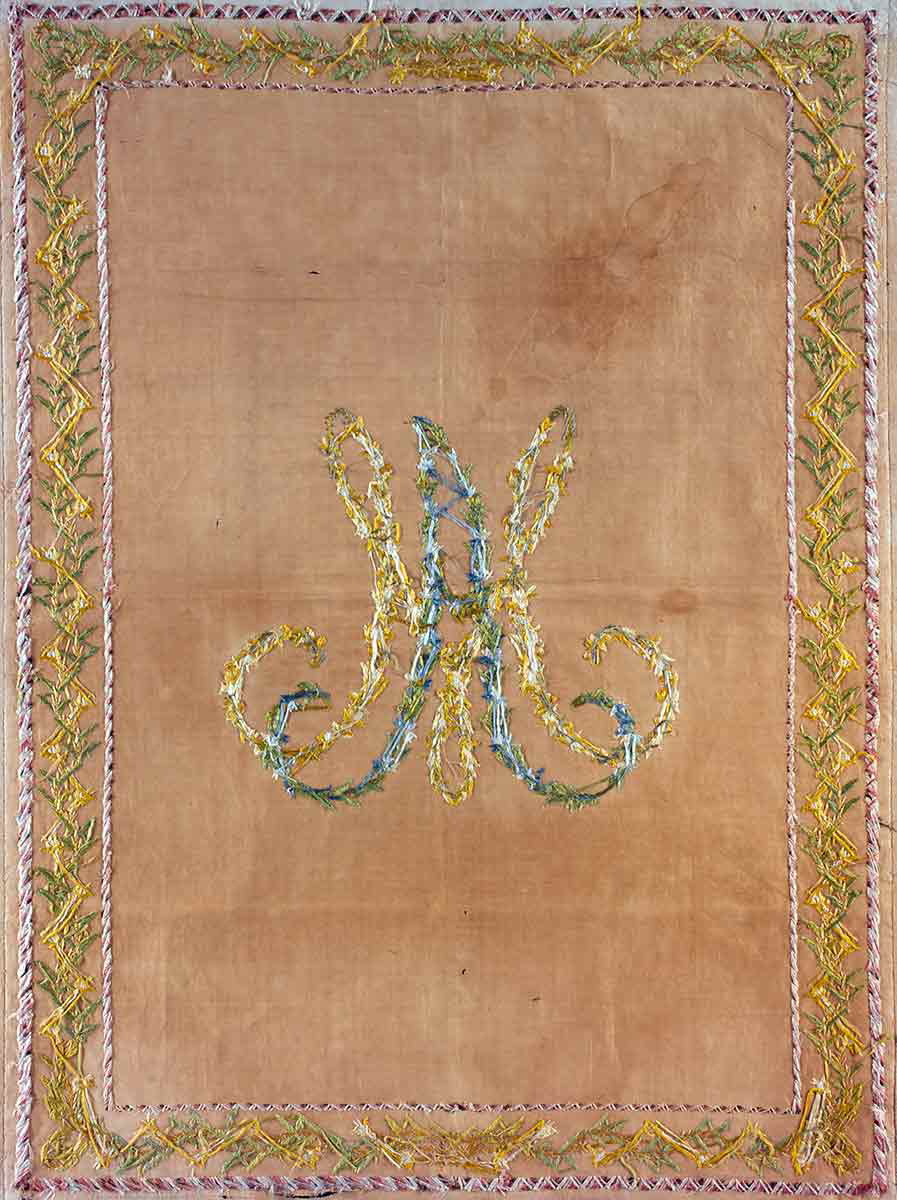

Elaborate intricate embroidery, especially made with gold or silver thread, was the marker of wealth and status. Remarkable examples of embroidered garments or accessories, especially those created in the East, traveled all over the world as collectible pieces of highly revered art. Embroidery was a luxurious element that demanded hours and hours of hard labor and thus served as a symbol of power and influence. In Christian cultures, it was also widely adopted for creating religious images and church decorations, illustrating the devotion of masters to God.

Traditional embroidery often had ritualistic and protective functions. Particularly in Eastern Europe, embroidered garments served as amulets that protected the wearer from evil eye or bad luck. Embroidered cloths and towels were, and occasionally still are, used during weddings and funerals or the rituals centered around introducing a newborn child to their family. Initially, each element of such embroideries had a specific meaning, yet a significant part of explanatory sources did not survive. Some embroidered works told entire stories of mythical characters, historical figures, or formative events for the culture in which they were created.

During the Renaissance, wealthy Italians commissioned embroidered tapestries and large-scale works to decorate their homes. The craft was so popular that many famous artists, including Raphael, created embroidery designs.

The Feminine Craft

For most of history, embroidery was categorized mostly as a feminine craft. Women were occupied with it during long evenings inside their homes, while men were busy with handling the affairs of the external world. Even the most high-status women, like Marie Antoinette, learned and practiced embroidery. Being good at it was regarded as a valuable asset for a good marriage, and not only for the reasons of acquiring a great skill: embroidery required patience and concentration and occupied a significant portion of women’s time, thus making them docile and quiet. For that reason, feminist artists of the modern era often rejected this type of medium, viewing it as inherently patriarchal.

This gendered aspect of embroidery practice had a destructive effect on its preservation and study. Dismissed as a domestic hobby, the rare studies of it were ethnologic rather than art historical, and the massive amount of knowledge, beliefs, and meanings simply disappeared over time.

The Revival of Crafts

Embroidery calmly existed as a domestic decorative practice until the late 19th century, when a group of artists, upset by the side effects of the Industrial Revolution, turned their gaze toward mediums previously discarded as mere “crafts.” The Arts & Crafts Movement, led by the famous William Morris, highlighted the unification of production processes and the devaluation of manual labor. For that purpose, they wanted to revive traditional decorative practices and incorporate them into the design of everyday objects and furniture. Embroidery was an important medium used in the movement, with William Morris even publishing books with embroidery schemes.

A few decades later, in France, a group of artists set out to dismantle the traditional hierarchy of arts. The group called themselves Les Nabis (an incorrect transliteration of the Hebrew word for prophets) and called for a new artistic era where forms and mediums would be treated equally. The group consisted of famous artists like Pierre Bonnard and Maurice Denis and was heavily inspired by Japanese art and various Eastern cultures. The principal members of the group were men, yet they often worked together with women from their families: the wife of Paul Ranson created embroideries based on his paintings, and the mother of sculptor George Lacombe wove tapestries filled with occult signs.

Asylum Patients & Embroidery

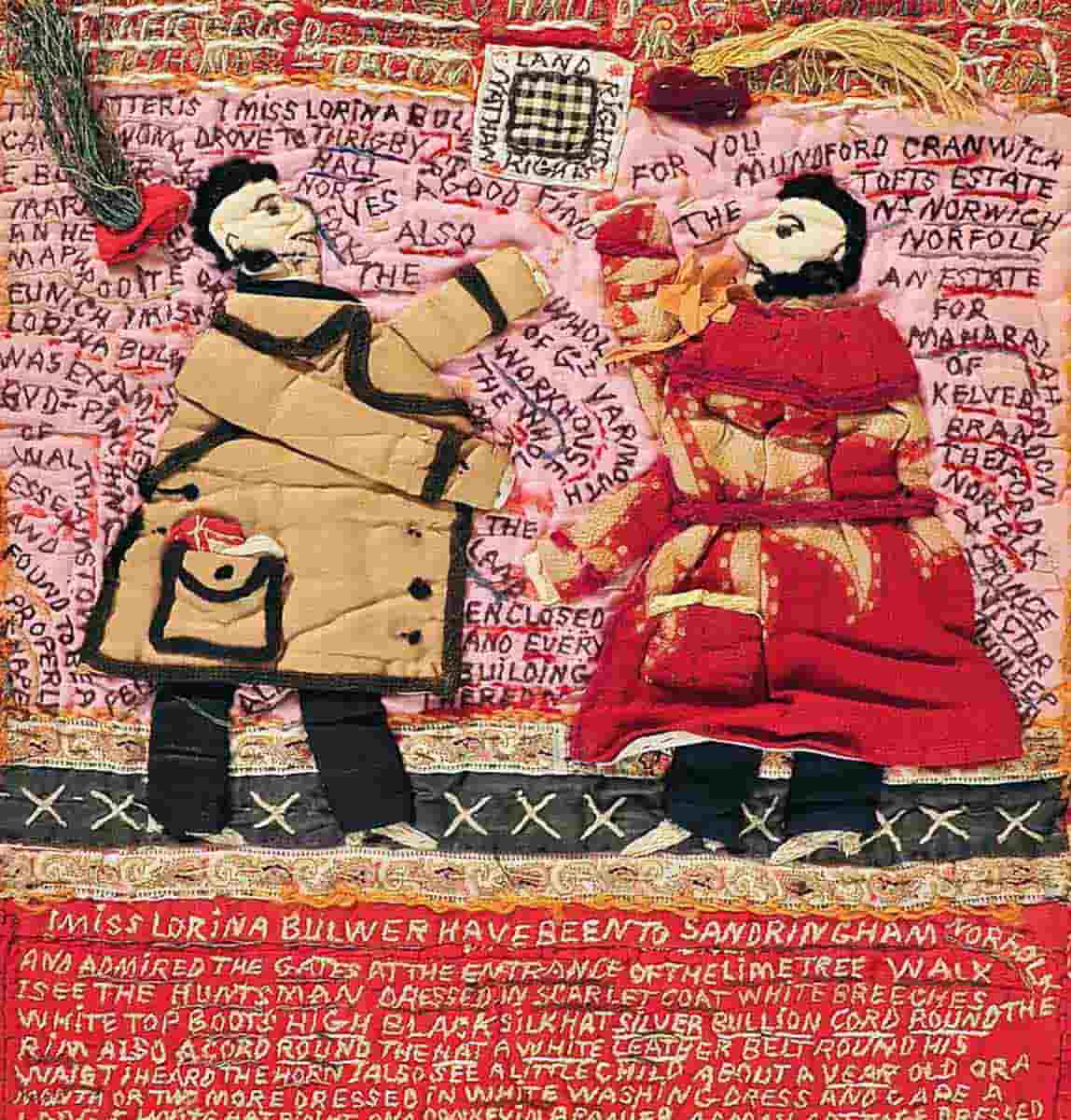

The practice of embroidery received a sudden upsurge of interest with the development of psychiatry. In the final decades of the 19th century, doctors began paying attention to artworks created by the asylum patients as part of their recovery program. Those who were stable enough to work were often forcefully employed in workhouses, sewing garments. Many women, who were often admitted into asylums after being discarded by relatives, expressed their frustration and fears in their work.

One of the most famous patients in that category was a seamstress named Lorina Bulwer. Bulwer was admitted to a workhouse after her parents died, and her brother paid the asylum staff to keep her there. Frustrated and angry, Bulwer expressed her feelings in detailed embroidered texts, all made in uppercase letters with no punctuation marks, including the tragic remark I HAVE WASTED TEN YEARS IN THIS DAMNATION HELL FIRE. Apart from expressing her distress, Bulwer created entire comic book-like stories by sewing on characters and objects and adding text to them. Some of the stories she told in these objects made present-day researchers suspect she endured sexual abuse during her incarceration.

Another famous woman known for her embroideries made in an asylum was Agnes Richter. Richter was a German woman in her late forties who was admitted to a hospital due to a suspected paranoia. During her 25 years of isolation, she made her own clothes and embroidered them with short phrases describing her life. The most prominent motif was the number 583, which she used to mark her clothes for the laundry, along with memories or random thoughts. Unfortunately, from a supposedly vast collection, only one jacket survived. The interest in works by self-taught artists like Richter or Bulwer peaked in the 1970s with the emergence of Outsider Art.

Judy Chicago’s “Dinner Party”

One of the most famous 20th-century artworks incorporating embroidery was The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago. The large-scale installation was a tribute to important women of Western history, as well as the celebration of the “feminine” arts and crafts, including embroidery and flower painting. Chicago presented a triangular table set for 39 persons. Each place had an embroidered name of a woman, a set of glasses, and a plate with a porcelain vulva-shaped flower composition unique for each name. Each side of the triangle had 13 seats, thus referring to the Biblical Last Supper, with only men present. Together, the installation combined a variety of crafts traditionally attributed to women and presented them in a grandiose and somewhat ritualistic setting.

In her other projects, Judy Chicago also employs embroidery as a feminist medium, with which she can introduce themes previously ignored by art history. Particularly, her woven and embroidered series The Birth Project reverently recounts the process of childbirth, turning it from an artistic taboo into a sacred ritual.

Embroidery in Contemporary Art

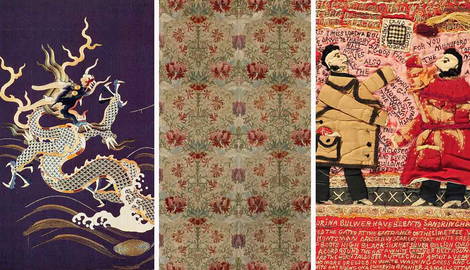

Today, embroidery is one of the most popular practices in contemporary art, not in the least because of its transforming connotations. Instead of dismissing it as a patriarchal craft, women artists embrace it as a practice shared by millions of women before them. The creative and spiritual potential of this practice was revived and turned into a powerful statement that often protests against inequality and oppression. Moreover, in terms of labor required to create an embroidered work, this medium acts as an opposition to the rather swift (or at least, seemingly swift) practice of gestural abstract art that dominated the market for decades.

The 2024 Venice Biennale placed a strong emphasis on artists who work in the domain related to or directly originating from Indigenous art practices. Many such artists work with fabrics and embroidery, sometimes combining it with other mediums and influences. Thus, Mexican artist Frieda Toranzo Jaeger presented a large-scale installation that blended painting typical for Mexican Muralist art with small embroideries scattered around the work. The national pavilion of Uzbekistan presented traditional Suzani embroidery and juxtaposed it with AI-generated images that revealed the cultural bias and stereotypical thinking of technology.