Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Augustus Pius, better known to history as the Roman emperor Antoninus Pius, was something of a Roman anomaly. The history of this emperor contains no accounts of military derring-do, no rousing speeches delivered to the armies of the empire, nor episodes of shocking deprivation and excess. On the contrary, Antoninus remained in Italy, content to focus on the management of the empire as he had inherited it from Hadrian and otherwise seemingly living the life of an exemplary Roman aristocrat. Below are 8 facts on the Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius’ life.

Honor Thy (Adoptive) Father: Antoninus Pius And Hadrian

Antoninus was born in AD 86 in the ancient city of Lanuvium – just a short distance to the southeast of Rome – to an aristocratic family who hailed from Nemausus (modern Nîmes) in southern France. His father, Titus Aurelius Fulvus was consul in AD 89 and had a family history of backing the right sides in imperial politics. His father, also called Titus Aurelius Fulvus, had wisely backed Vespasian during the Civil War of AD 68-69 and had been duly rewarded under the Flavian dynasty.

His father’s death shortly after his consulship led to Antoninus being raised by his maternal grandfather, Gnaeus Arrius Antoninus, a similarly well-respected Roman aristocrat. Antoninus married Annia Galeria Faustina the Elder, with whom he was to enjoy a long and happy marriage, between AD 110 and 115. Faustina was in fact, related to the Empress Vibia Sabina – unhappy wife of Hadrian – bringing Antoninus closer into the imperial circle.

Antoninus Pius followed the typical career path of young, noble Roman men, serving as quaestor, praetor, and excelling as the proconsul (governor) of Asia in AD 134-35. Already a favorite of Hadrian, his proficiency as an administrator served him well. He was nominated as Hadrian’s heir in February 138. However, Antoninus wasn’t the first choice; he was picked by Hadrian only because Lucius Aelius had died, and what’s more, Antoninus was chosen only on the condition that he would in turn adopt Marcus Annius Verus and Lucius Verus.

When Hadrian died in 138, his frosty relationship with the Senate – he had ordered the killing of several members during his reign – saw them reluctant to bestow on the deceased emperor the usual honors, including the recognition of his divine status. However, one of the very first acts of Antoninus’ reign was to pressure the Senate to recognize the former emperor. It is widely believed that it was this act of pious, filial duty towards his adoptive father that earnt him the title Pius. However, one should not lose sight of how beneficial it would have been for the new emperor to have a deified father to provide legitimacy to his own reign… Pious though he may have been, it is clear that Antoninus Pius was a shrewd political operator.

Settled Roman Emperor, Settled Empire: Antoninus Pius In Italy

Antoninus’ reign as emperor is characterized by a prevailing sense of stability and sensibility. His piety assured by the honor paid to his imperial predecessor, it was also alleged that the title Pius reflected his intervention on behalf of senators condemned by Hadrian. The imperial administration was, according to epigraphic evidence, particularly conservative during the reign of Antoninus. A close-knit group of senatorial families worked with the emperor to oversee the running of the empire, and the trust Antoninus placed in them is indicated by his never leaving Italy during his reign. This style of government was well-received in antiquity, with late antique writers, such as Aurelius Victor, commending the fact that the people of the empire looked upon him more as a parent or a patron, than a master or emperor.

Like other Roman emperors, Antoninus Pius oversaw vast construction projects around the Empire, including in Rome. His most famous architectural legacy in the city is the colossal temple of Antoninus and Faustina in the Forum Romanum, which was subsequently reused by the Catholic Church as the Church of San Lorenzo in Miranda. Much of his work in the city itself focused on rebuilding and restoring important landmarks around the city. These included the Historia Augusta alleges, the Pons Sublicius, the oldest bridge across the Tiber in the city. This was a recurring theme of Antoninus’ reign, notably less of the construction of ostentatious monuments, and rather for those projects that benefitted the imperial populace – such as the baths at Ostia – and the vital arteries of imperial infrastructure: roads, bridges and aqueducts.

Peace And Prosperity: Antoninus, The Army And The Economy

As well as piety, Antoninus is well known as a Roman emperor for his peaceful approach to imperial management. Whether or not it was a cause or a consequence of his decision never to leave Italy, the period of his reign – from AD 138 to 161 – was the most peaceful in all of Rome’s imperial history. No foreign wars of rapacious conquest or punitive justice were waged against Rome’s neighbors during these 23 years. Although there were several instances of violent disturbances in the empire, these were usually focused on competition between ambitious Roman administrators, rather than against external threats.

Such was the style of Antoninus’ government that even in the instance of attempted usurpation, the emperor allowed the members of the Senate to dispense justice against those who had attempted to seize power. Elsewhere, there were no great uprisings, such as Hadrian had to quash in Judaea, and Antoninus chose to respect the imperial strategy of his predecessor and recognized the limits of the empire.

The armies of the empire, distant from Italy, were kept informed of their new emperor through his presentation on coinage. He may he opted not to travel to the imperial frontiers to meet with them in person, but they would certainly have been made aware of the emperor and his ideas through his numismatic representation. In fact, the economy and coinage were central to Antoninus’ reign. Despite his extensive building projects around the empire and in the capital, he still managed to leave a substantial surplus – around two and a half million sesterces – in the imperial treasury at the time of his death. Nevertheless, he was not avaricious in taxation, famously suspending it in those cities who suffered the misfortune of a natural disaster.

A Lover, Not A Fighter: Antoninus Pius And Faustina

Antoninus’ marriage to Faustina the Elder was a happy and fortuitous marriage. Not only did Faustina’s familial connections appear to have directly benefitted Antoninus’ careers (and eventual elevation to an imperial heir) but also, unlike other imperial marriages, there appears to have been genuine love and affection. Together they had four children, two sons and two daughters. Unfortunately for the couple three of the children – both sons and one of the daughters – all died before AD 138. The surviving child, Annia Galeria Faustina Minor (also known as Faustina the Younger), grew up to be a future empress as the wife of Marcus Aurelius and mother of Commodus. As a reflection of her importance to Antoninus and her role as the imperial mother, she was granted the title of Augusta by the Senate, which was a sign of public respect and a clear indication of her status.

When Faustina died in AD 141, Antoninus Pius was plainly devastated by the loss of his wife. His grief found expression in a number of magnificent monuments across the imperial capital. Chief amongst these, of course, is the Temple of the Deified Faustina – to which the cult of Antoninus would be added after his death – in the Forum Romanum. The temple was built in honor of her being deified by the Senate, and a number of coins were minted bearing the legend DIVA FAUSTINA to ensure that the imperial populace knew of her joining the gods.

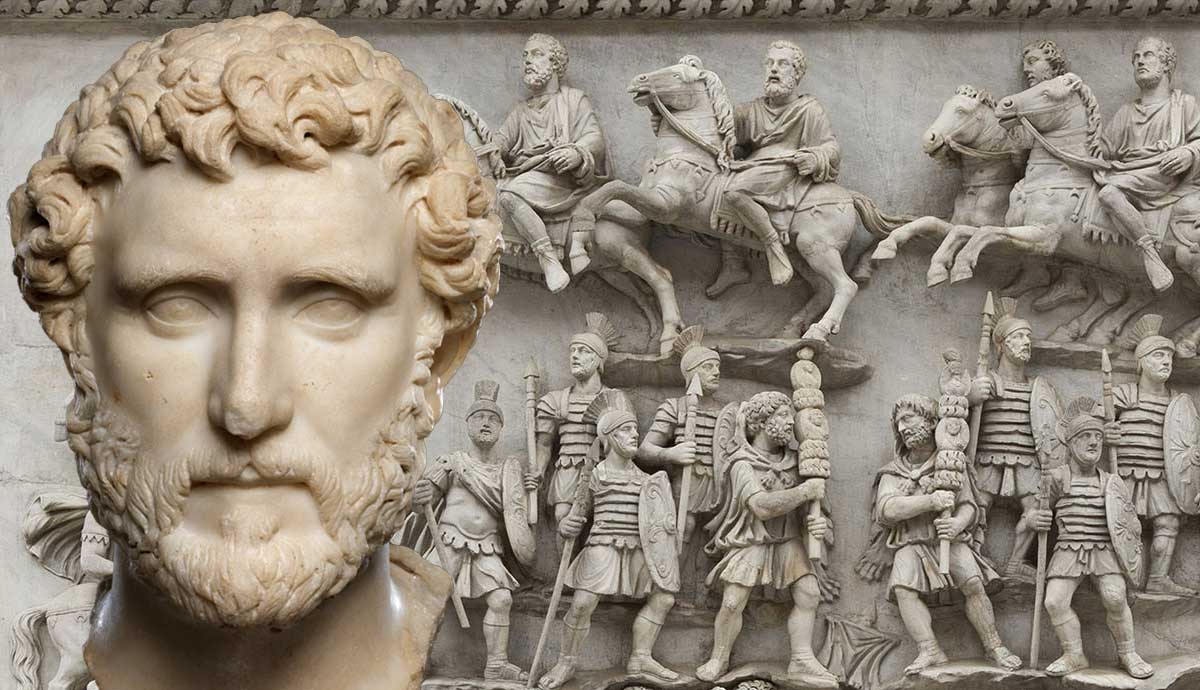

The most evocative representation of this deification however is presented in a relief sculpture from the base of the Column of Antoninus Pius, which is now displayed in the Vatican Museums. Set up in the Campus Martius by Marcus Aurelius to honor his deceased predecessor, the ornate relief decorations on the base (unfortunately all that survives of the monument) includes a depiction of Faustina and Antoninus being carried away on the back of a winged Genius as they ascend to the heavens.

Assessing Antoninus: The Sources

Making sense of Antoninus’ reign can prove a challenge to historians. Despite overseeing perhaps the most tranquil period of Rome’s imperial history, the life and reign of this emperor are not well recorded by contemporary sources. The only complete biography that survives can be found in the Historia Augusta, a collection of imperial biographies produced in the late 4th century and often rich in scandalous falsehoods and lurid gossip. That being said, for the reign of earlier emperors, it is often possible to ascertain elements of truth in this text. The account of Antoninus’ reign recorded in this history of Cassius Dio, a Greek senator writing during the reign of the Severan emperors, is unfortunately almost completely lost; fragments alone remain.

Historians have pondered whether the very lack of conflict in the empire during the reign of Antoninus Pius was responsible for the dearth of contemporary historiography; it is telling that the reign of Lucius Verus and Marcus Aurelius after Antoninus – wracked by war, violence and a terrible plague – would lead the historians to pick up their pens once more.

The reign of Antoninus Pius may also be pieced together using the anecdotes and traditions that were preserved by later historians. The future emperor Julian, writing in the 4th century, presents the economic fastidiousness of Antoninus, characterizing him as a “cumin splitter”. The historian Eutropius provides a more balanced, less tongue-in-cheek portrayal of Antoninus, describing his good reputation: “a man of high character, who may justly be compared to Numa Pompilius [Rome’s mythical second king, and a man of law]”. Elsewhere, Antoninus’ reign may be reconstructed through archaeological evidence including numismatics (coinage), archaeological, and epigraphic (inscriptions). Indeed, the epigraphic evidence is rich in providing examples of the relationship the Roman emperor enjoyed with the imperial provinces he never visited; numerous examples survive of his responses to petitions from cities around the empire who have sought the emperor’s intervention in resolving a local issue.

Empire Edges And Beyond: Antoninus, Britain And China

Despite his decision to remain in Italy, Antoninus Pius nevertheless remained actively involved in the administration of the empire and was well aware of the world outside of Rome. Although a reign of peace, Antoninus did in fact order an aggressive incursion into the north of Britain. Led by Quintus Lollius Urbicus, a governor of African (Numidian) descent, the Romans invaded the south of Scotland and achieving a number of notable victories and pushing back the imperial frontier beyond that established by Hadrian’s Wall.

To mark the new imperial boundary – which ran from the Firth of Forth to the Firth of Clyde – the Antonine Wall was built. The Antonine Wall was different from the earlier Hadrianic fortification in that it was built predominately of turf, not stone. The lack of benefit to acquiring this additional territory – the land was barren – and the costs involved in manning the new fortification have led some to ponder whether the whole campaign was conducted purely to provide Antoninus with a modest military victory upon which to further boost his legitimacy as emperor.

It wasn’t just the north that Antoninus took an interest in. He was the emperor responsible for what is believed to be the first diplomatic mission from Rome to China! A group of people claiming to be sent from Rome arrived in China, at the court of the Emperor Huan (of the Han Dynasty) in AD 166; recorded in the Hou Hanshu, or Book of the Later Han, they are described as having been sent by the King of Daqin, meaning Rome. The Chinese historian makes clear that this is the first instance of direct contact between China and Rome!

Although the emperor in question could also be Marcus Aurelius (who was reigning in AD 166 and also called Antoninus), the discovery of golden medallions from the reign of Antoninus found in the Far East do indicate the relationship between the two great powers. A number of Roman coins from across the imperial period have been found in China, notably at Xi’an, and it appears that the Romans desired the luxury goods produced in the Far East, notably silk.

A Divided Succession: Antoninus, Marcus Aurelius And Lucius Verus

Although the premature death of the male children of Antoninus and Faustina’s marriage meant that the succession of imperial power would have to involve external actors, this had already been guaranteed by Hadrian. His adoption of Antoninus as his heir was predicated on the future-emperor. In turn, he adopted Marcus Annius Verus and Lucius Verus, relatives of Lucius Aelius, Hadrian’s first choice as a successor who had predeceased him.

To confirm the adoption of the young men into the imperial household, Antoninus had Marcus annul his betrothal to one Ceionia Fabia. Instead, he was to be married to Faustina the Younger, the sole surviving child of Antoninus and Faustina. Their involvement in the state from an early age further cemented their position as the imperial heirs. By AD 140, Marcus had already been made consul (in partnership with Antoninus), and the title of Caesar, a clear indication of his status in the empire.

Antoninus’ long reign, inclination towards peace and generally good government meant that he was one of those rarest of Roman emperors in being one who died of old age. When he eventually died in AD 161, he was 74 years old. He had been showing the signs of debilitation and old age for some time; the Historia Augusta records that his once-imposing stature was diminished by the stooping of age to such an extent that he took to wearing wooden stays to keep him upright!

In keeping with his character, Antoninus even had the pragmatic sense to die in good order. Having realized his condition was deteriorating – a particularly large portion of “alpine cheese” is said to have brought on a nasty fever – he called Marcus Aurelius to him and formally committed the empire to him. He died at his country estate in Lorium, but his body was returned to Rome where his remains where interred in the Mausoleum of Hadrian. Like his beloved wife Faustina, Antoninus was also deified.

Antoninus Pius And The ‘Five Good Emperors’

It would be some time again before an emperor enjoyed a reign as long as Antoninus; not until Constantine the Great in the early 4th century would an emperor oust him as the second-longest reigning Roman monarch. His predecessor Marcus Aurelius would arguably go on to surpass Antoninus as the paradigm of a good emperor, but in overseeing a reign that ushered in decades of internecine war, pitching Roman against barbarian and Roman against Roman, the zenith of Rome’s imperial zenith had arguably already passed by the time Antinous died in AD 161.

The peace and piety that characterized his reign have seen modern audiences turn away from Antoninus Pius. Unlike the madness of Nero, the cruelty of Commodus, or even the depravity of Elagabalus, centuries of scriptwriters, dramatists and artists have found little drama and scandal to plunder here. However, fuelled by the praise of the Romans themselves, the historians of Rome have been especially kind to Antoninus. His firm but fair rulership – and especially his relationship with the Senate (as opposed to an overt autocracy) – have proved fertile ground from which effusive praise has grown.

Most famous of all is perhaps Edward Gibbon, the Enlightenment historian and author of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire between 1776 and 1788. He presented Antoninus Pius the penultimate of his ‘Five Good Emperors’. In characterizing Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus and Marcus Aurelius as such, he wrote that “if a man were called upon to fix the period in the history of the world during which the condition of the human race was most happy and prosperous, he would, without hesitation, name that which elapsed from the death of Domitian to the accession of Commodus”. He may not have been Hadrian’s first choice as successor, but there are few who would argue that Antoninus Pius left his own imperial heirs an empire in very fine shape. It was a height that, arguably, it would never reach again.