In Japanese mythology, after the goddess Amaterasu sent Ninigi to conquer Earth, the Sun’s grandson had children who had children of their own who had children of their own as each generation lost a little bit of their divinity until the Age of Gods gave way to the Age of Humans. The date at which this happened is often given as 660 BCE, when Emperor Jimmu became Japan’s first sovereign. But while he was (represented as) a human, he became as important to Japanese culture as his divine ancestors.

Sources and Facts

There is no debate over the historical authenticity of Emperor Jimmu. He never existed. He is a legendary figure, one of many used to fill in the gap between Ninigi, the Earth-bound grandson of the sun goddess Amaterasu, and the first historically verifiable Japanese rulers. But just because he was not real does not mean he was not important to Japanese culture or history. His ascension in 660 BCE is often regarded—mostly symbolically—as the beginning of “Japanese history” (Aston, W. G., p. 132). As the first chapter in the post-Age of Gods books in the 8th-century Kojiki and Nihongi chronicles, the story of Jimmu was undoubtedly an important source of information for the imperial court, even if most of it was not factual.

Or was it? Some scholars propose that the movements of Jimmu and his army could be “a legendary echo” of real migrations from the Japanese island of Kyushu towards the mainland (Aston, W. G., 2008, p. 109). It is said that many legends contain a kernel of truth in them, and perhaps this was also the case with Jimmu, but it is all speculation at this point. For now, let us concern ourselves with the lessons found within the story of Emperor Jimmu without worrying whether any of it really happened or not.

Deeds Over a Genetic Lottery

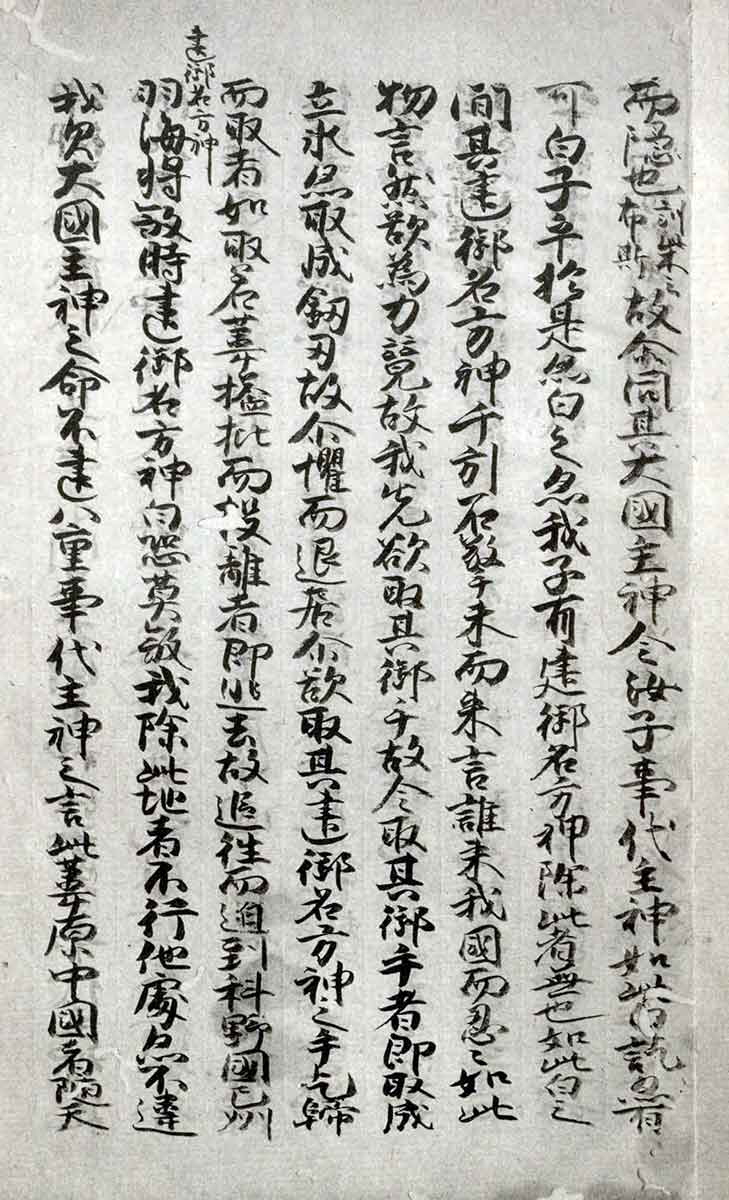

The Kojiki and the Nihongi (a.k.a. The Nihon Shoki) detail the story of Jimmu’s conquest of Yamato in central Japan, corresponding to modern-day Nara, which borders other centers of power like Kyoto. The chronicles go about it very differently, though. The Kojiki treats it all almost as a fable, a mystical voyage of a chosen one taking what the gods had set aside for him. The Nihongi uses a more realistic approach, portraying Jimmu as a military commander at the head of an army. But the two do agree on the finer details, like Jimmu’s lineage.

Jimmu is the first emperor’s posthumous name meaning “Spirit Warrior” (Yasumaro, O., p. 209) or “Divine Valour” (Aston, W. G., p. 109). In life, he was known as Kamu-yamato Iware-biko, the youngest of four children. He starts his journey from Kyushu towards Yamato with his older brother Itsuse, but in the end, it is Jimmu—who will be identified by this name going forward—that ends up taking the throne. Even though it was mainly because of Itsuse dying along the way, it is still deeply meaningful that a younger brother becomes sovereign. To make sure the lesson sinks in, the Jimmu chapter in the Kojiki ends with his children fighting over the right to be his heir. One of Jimmu’s oldest, Tagishimimi, plans to murder his step-siblings, but gets taken by surprise and killed (in self-defense) by Kamu-nuna-kawa-mimi, after his older brother failed to act. For his bravery and initiative, Kamu-nuna-kawa-mimi succeeded Jimmu as Emperor Suizei.

The Jimmu chapter is therefore evidence that the idea of primogeniture did not exist at the start of the Japanese imperial line. What earned one a spot on the throne was not a genetic coinflip and timing but rather great deeds. Second, third, even fourth sons had the right to rule if they just proved themselves more worthy than their older siblings. This is very different to how things work today, with Chapter 1, Article 2 of Japan’s Imperial House Law saying very clearly: “The Imperial Throne shall be passed to the members of the Imperial Family according to the following order: 1. The eldest son of the Emperor, 2. The eldest son of the Emperor’s eldest son (…)” (emphasis added).

Marriage as a Weapon

During his conquest of Yamato, Jimmu encountered much opposition, including people with tails who might have been stand-ins for the Ainu or Emishi indigenous ethnic groups. One of the earliest enemies that Jimmu fought was Nagasunehiko, a local chieftain who ended up shooting Itsuse in the arm and inflicting what was ultimately a fatal wound. Jimmu had continued on without his brother all while planning his vengeance. Later on, when hunting for Nagasunehiko, he sang this song:

“Hunt for its roots

seek out its shoots,

strike and put an end to it.” (Yasumaro, O., p. 67)

The song clearly indicates that Jimmu was planning to wipe out his enemy and all of his family. And yet, when the heavens sent the kami Nigihayahi to serve Jimmu, the deity married Nagasunehiko’s sister, Tomiyasubi-hime aka Mikashigiya-hime. This was a gift for Nigihayahi and Jimmu showing mercy by giving Nagasunehiko a chance to submit to him (as his brother-in-law’s lord) without losing face. But he refused and so he was killed.

Future Japanese warlords would use similar strategies, treating marriage as a diplomatic tool. In the 16th century, Saito Dosan, known as “The Viper of Mino,” recognized the future threat and potential of his neighbor, Oda Nobunaga, and arranged for him to marry his daughter Nohime to tie the fates of their clans together. It was not a total success as Dosan eventually lost Mino, which was later occupied by Nobunaga. But Dosan’s idea was sound and echoed a strategy whose roots go back thousands of years.

As for Jimmu, he also married strategically when he felt it was necessary. He had multiple wives, and one of them was Hime-tatara-isuke-yori-hime, daughter of powerful kami. The details of her parentage differ between the Kojiki and Nihongi but Hime-tatara-isuke-yori-hime’s heavenly lineage is unquestionable. Making her empress elevated Jimmu’s status and made his conquest seem even more heaven-blessed. The couple’s union became official after they slept together, explaining the importance of consummation in royal and noble pairings, as seen in the song sung by Jimmu:

“On a reed-filled plain,

in a cramped and dirty hut,

atop woven mats of sedge

spread to refresh the visitors,

have we slept together.” (Yasumaro, O., 2014, p. 71)

The Importance of Symbols

As a descendant of the Sun herself and with kami deities by his side, Jimmu’s conquest of Yamato was clearly blessed by the gods. But this most likely meant little to the common man who knew little of exalted lineages. The commoners needed something more concrete to rally around. The Japanese gods apparently agreed and so they sent Jimmu a great sword.

Amaterasu and the god Takaki appeared in the dream of one Takakuraji, telling him that they sent a weapon for Jimmu, which could be found in his storehouse. After waking, the man searched his storehouse and indeed found a heaven-sent broadsword inside. He brought it to Jimmu who at the time was fighting dangerous spirits of the mountains. Explaining that the sword’s names were Sajifutsu (Glinting Slasher), Mikafutsu (Stern Slasher) and Futsunomitama (Slashing Mighty Soul), Takakuraji handed Jimmu the weapon. When he grasped it, the spirits of the mountains were “cut down by themselves.” (Yasumaro, O., p. 63.)

Divine swords used as symbols of power are not, of course, exclusive to Japan. The trope appears in many stories over many centuries and territories. There is the famous Excalibur from Arthurian legend, which proved King Arthur’s right to rule in Britain and, in some versions, was bestowed to him by a deity–the Lady of the Lake. In France, they tell the story of the unbreakable Durandal from the Song of Roland about a paladin of Charlemagne. Believed to contain a tooth of Saint Peter and the blood of Saint Basil, it is no wonder the weapon is sometimes described as “the French Excalibur.” In Norse mythology, there is the Gram (a.k.a. Balmung or Nothung) from the Völsunga Saga, the blade that Sigurd used to slay the dragon Fafnir. Showing similarities to the sword in the stone legend, the Gram was inserted into a tree by Odin and could only be pulled out by a mighty warrior.

Getting back to Jimmu: the god Takaki also sent the first emperor a three-legged raven to guide him. The Yatagarasu is an import from China where it is known as Yangwu, a crow said to be a great navigator who, more importantly, lives in the Sun. The mystical crow’s connection to the Sun additionally confirms Jimmu’s lineage and, together with the Slasher, acts as a tangible symbol that his soldiers and the people could gather around. Even today, the Japanese Imperial Family places a lot of value on symbols, with the Three Sacred Treasures of Japan (a sacred mirror, sword, and jewel) being “regarded as proof of the status of the Emperor.”

Works cited:

Translated by Aston, W. G. (2008). Nihongi Volume I – Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Cosimo, Inc.

Yasumaro, O., translated by Heldt, G. (2014). The Kojiki, An Account of Ancient Japan. Columbia University Press.