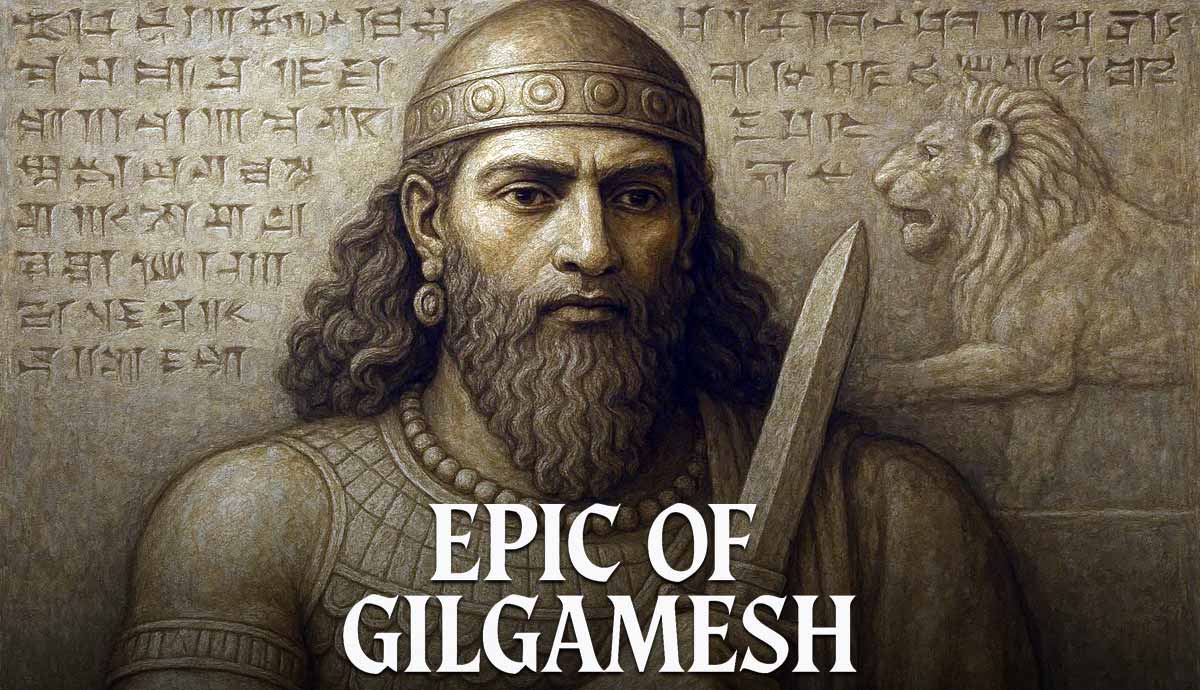

The Ancient Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh is widely known as the world’s oldest literary epic. The story rivals the Homeric epics of ancient Greece in its portrayal of gods, heroes, and monsters alongside a seemingly impossible quest for immortality. Multiple versions of the story were written over several millennia, confirming the widespread popularity of the tale. But what exactly is the Epic of Gilgamesh, and what happens in the story?

What Is the Epic of Gilgamesh?

The Epic of Gilgamesh follows the life and adventures of Gilgamesh, the semi-divine ruler of the Sumerian city of Uruk, located in what is now southern Iraq. Although the tale about him is fictional, most historians believe that Gilgamesh was an actual king of Uruk, whose life and exploits were later embellished in subsequent generations. Both the literary and historical Gilgamesh lived sometime between 2750 and 2500 BCE, at the dawn of civilization. According to historical Sumerian records, he was credited with building Uruk’s walls, which is attested to in the epic. He is also mentioned in other historical texts, reinforcing the probability that he was a real person. Whoever Gilgamesh actually was, he was deified after his death, and epic tales were written about his life and adventures.

The epic tale of Gilgamesh was lost to the modern world until the mid-19th century, when the library of the Assyrian monarch Ashurbanipal was discovered in Nineveh, modern-day Mosul, Iraq. Twelve tablets were found written in Akkadian, using the cuneiform alphabet, and were recorded sometime in the 7th century BCE. These remained undeciphered until the 1870s, when the language was decoded by George Smith, who worked at the British Museum. This collection of tablets represented the most complete version of the text, but was still fragmentary. Several of the fragile clay tablets were damaged, leaving gaps in the narrative. As a stroke of luck, in later decades, these gaps were filled in by other fragments found in other locations in the Near East and Anatolia.

In addition to these Akkadian tablets, Gilgamesh’s tale is also recorded in several much older surviving poems. Written in the Sumerian language, the five short poems detail events in Gilgamesh’s life. Some of the poems align with the main narrative, although others describe incidents that do not correspond with the twelve original tablets. Even with these additional sources, some gaps remain in the story.

The Story Begins

Gilgamesh, king of the city of Uruk, is the greatest and mightiest man of his age. He is two-thirds god and one-third man, and rules over his subjects with an iron fist. After completing the massive walls around the city, the people cry out to the god Anu for relief from oppression. The deity hears their pleas and instructs the goddess Aruru to construct the wild man Enkidu. After his creation, Enkidu lives among the animals in the wilderness around Uruk, frightening a hunter, who brings word of the wild man to Gilgamesh. Rather than confront Enkidu directly, the king suggests that he first be seduced by Shamhat, a temple prostitute. The encounter with Shamhat civilized Enkidu, who was then able to speak and reason like a civilized person, and eat bread and wear clothing, rather than eating grass like a gazelle. He then hears about the oppression caused by Gilgamesh and rushes to face him.

The two confront one another and fight. Enkidu and Gilgamesh are evenly matched and, over the course of their combat, become friends. Still wanting to make a name for himself, Gilgamesh then suggests that the pair go off to fight the monster Humbaba, who lives in the cedar forest. Enkidu agrees, and the pair take on the forest guardian, even though he has not wronged them in any way and was not a threat to them. They defeat Humbaba and celebrate their victory. This angers the gods, who had assigned Humbaba the task of guarding the sacred forest.

Still, both of the warriors are elated by their triumph, and Gilgamesh bathes and puts on his finest clothing. Since he is partially divine, he stands taller and is much stronger and more handsome than any mere mortal, which attracts the attention of Ishtar, the goddess of love and fertility. Gilgamesh rejects her, telling the goddess that misfortune plagues her lovers. Enraged at being spurned, she sends the Bull of Heaven to destroy Gilgamesh. The mighty beast rampages through Uruk, but by working together, Enkidu and Gilgamesh manage to subdue and kill the creature. Enkidu then takes a leg of the bull and throws it at Ishtar in contempt.

Enkidu’s Death, the Quest for Immortality & the Flood

Enraged at this insult to a fellow deity, the other gods decree that Enkidu must die. Over the next twelve days, Enkidu has dreams about his descent into the “house of dust,” a nightmarish realm where the souls of the dead endure. After these terrifying visions, he finally dies.

Gilgamesh is distraught by the loss of his friend and mourns for him. In his grief, the death of Enkidu also triggered an existential crisis in Gilgamesh. Though he is two-thirds divine, he is also one-third mortal, and will ultimately die one day. Determined not to let this happen, he makes the decision to seek out Utnapishtim, a human who had achieved immortality. He sets off, traveling through a hostile wilderness. He eventually reaches the tunnel of the sun god Shamash, which is guarded by a pair of scorpion monsters. The text is missing here, but he somehow convinces them to let him pass through the tunnel that no human had ever entered.

Once through the tunnel, he then enters the tavern, which is being run by the goddess Siduri. At first, Siduri thinks Gilgamesh is a thief because of his unkempt appearance, but Gilgamesh convinces her of his true identity and his quest to reach Utapishtim. Siduri tries to tell him that his quest is futile, but he insists on continuing. The tavern keeper relents and then sends him to the ferryman Urshanabi. The ferryman then takes him across the waters of death to reach his goal.

Once on the other side, Gilgamesh finally reaches his goal and is instantly disappointed. Utapishtim and his wife both live on an island and were granted immortality by the gods, so he has no power to do this himself. Utnapishtim was warned by the gods that they intended to flood the world and that he should build a boat to survive the waters. Much like the later story of Noah’s Ark, Utnapishtim sent out birds to see if the floodwaters had receded, and eventually, he and the animals on the boat were able to repopulate the world. As a result, the gods granted him immortality.

Gilgamesh’s Continued Quest for Immortality

Seeing Gilgamesh’s disappointment, Utnapishtim then gives the king a challenge. He tells him to stay awake for six days and seven nights without sleep. Gilgamesh agrees to this challenge and promptly falls asleep. To drive the point home, Utnapishtim has his wife bake a cake for each day he was asleep. When he awakens, Gilgamesh sees the cakes in various stages of decay, proving how long he was asleep. The point of this test is to show that if Gilgamesh cannot even conquer the mild challenge of sleep, how then can he escape death? Realizing that his quest for immortality had been in vain, Gilgamesh sets out with the ferryman Urshanabi to return to Uruk.

Nevertheless, there was a glimmer of hope. Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh of a plant that will not make him immortal, but will at least restore his youth, a small consolation. Unfortunately, the plant grows at the bottom of the sea. Undeterred by the inconvenient location, Gilgamesh ties stones to his feet and sinks to the bottom of the sea to find the magical plant. He then retrieves it and brings it to the surface. Unfortunately, when he takes time to bathe, a serpent snatches the plant and slithers off. Overcome by despair, Gilgamesh returns home to Uruk. Once there, he sees the grand walls of the city that he had constructed, and realizes that his greatest accomplishments will outlive his physical form and that he has achieved a type of immortality.

Most scholars believe the story ends here, but the twelfth Akkadian tablet recounts a scene from an earlier part of the narrative. Enkidu is still alive, and Gilgamesh tells him about several of his possessions that have fallen into the underworld. Eager to help his friend, Enkidu then descends into the underworld to retrieve these items and becomes trapped there. After appealing to the gods for help, one of the deities opens a crack in the earth so that Enkidu’s spirit can escape. The spirit then tells Gilgamesh of the harrowing fate that awaits the dead. This last tablet doesn’t match the overall narrative and may have been added later as an addendum or appendix, and is generally left out of retellings of the tale.

A Timeless Epic

The Epic of Gilgamesh is one of the oldest tales ever recorded, and speaks to humanity’s most basic instincts: the fear of death and the extreme lengths humans will go to avoid mortality. It is also a tale of humility, pride, ego, adventure, love, friendship, and the power of memory and reputation over the millennia. Though it is ancient and the specifics are unique to the era in which it was written, the themes of the story still resonate today as a meaningful and powerful exploration of humanity’s timeless struggles.