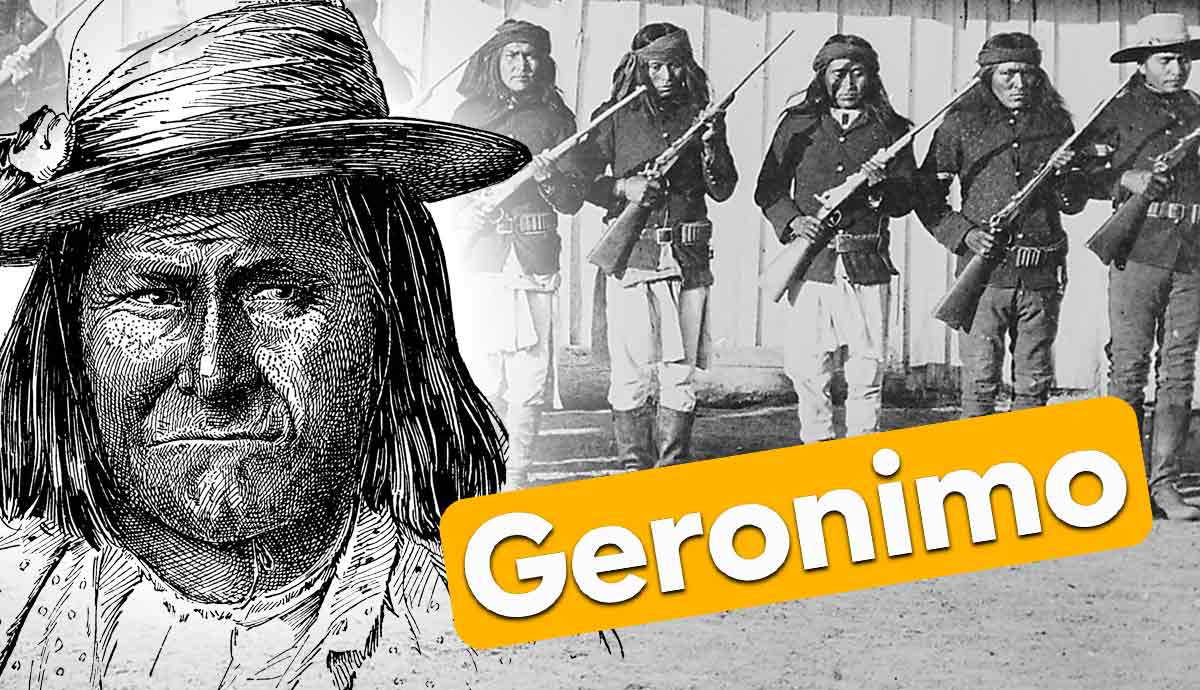

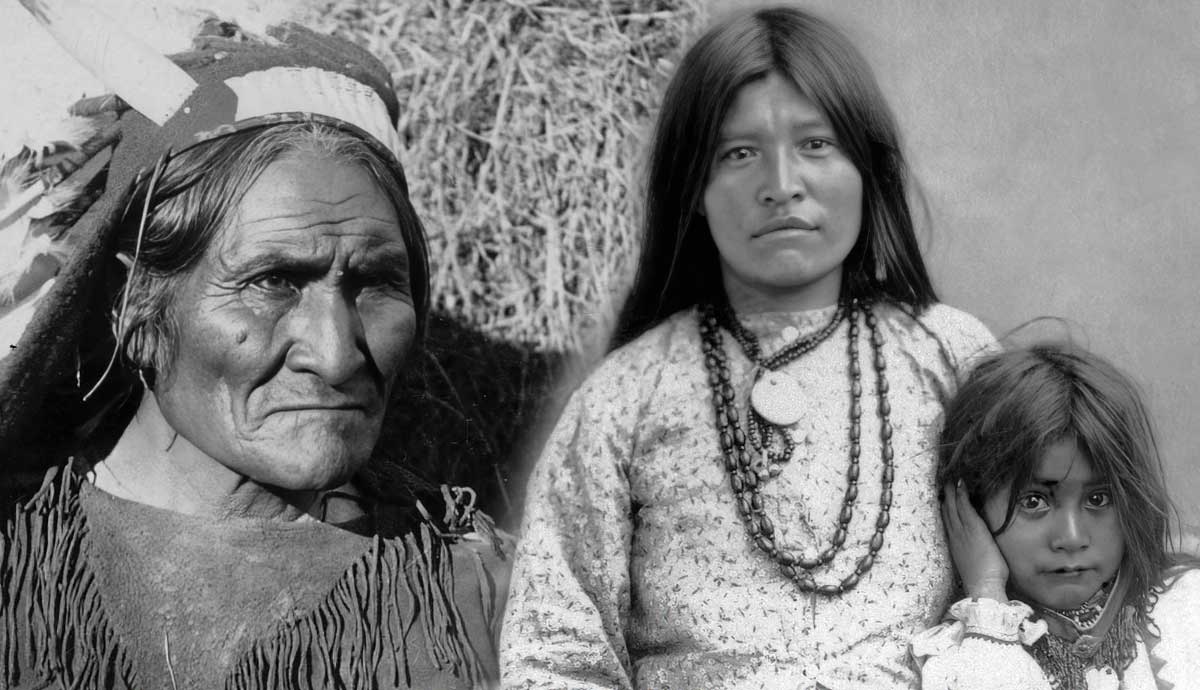

From early life as a fearless raider and warrior to the final decades spent as a prisoner of war, Geronimo was a defender of his people throughout his days. He became a symbol of Indigenous resistance not only against the United States government but Mexican forces as well. His fearless fighting style was what he was known for, but his personal story reveals that there was much more to the man behind the reputation.

1. Geronimo Was a Nickname

A member of the Bedonkohe band of the Chiricahua Apache tribe, Geronimo was actually given the birth name Goyahkla, meaning “One Who Yawns.” He claimed to have been born in June 1829, though an exact date was lost to recorded history. He did not earn his most famous moniker until later in life. While fighting the Mexicans in a series of raids and attacks throughout the late 1850s into the 1860s, Goyahkla earned a reputation as a fearless, vicious warrior who took no prisoners.

The Mexican soldiers called upon St. Jerome for protection in their frantic fighting. The Spanish version of Jerome—Geronimo—became associated with Goyahkla and would become his designation in the Mexican and American realms. He was said to have accepted the name.

2. He Was Driven by Vengeance

Geronimo is still well-known centuries later for his dedication to his people. However, many don’t realize that his fighting spirit was originally driven by revenge. In 1858, he was on a trading trip to the Mexican town of Janos. The women and children of the band stayed behind in the nomadic group’s encampment while the majority of the men visited the town to procure supplies. When the traders returned, they were horrified to find that Mexican troops had come to the camp, stolen ponies, destroyed supplies, killed the guards, and massacred dozens of women and children. Among the dead were Geronimo’s mother, his wife Alope, and their three children. His entire immediate family was wiped out, and Geronimo was devastated. He later wrote “I had no purpose.”

After a great deal of reflection, fasting, and grieving, Geronimo once again found a purpose, and this time, his goal was revenge. He vowed retaliation upon the Mexican army and anyone associated with them. Geronimo received permission from his chief, Mangas Coloradas, to gather support from his band’s warriors as well as other Apache bands, the Nedni and Chokonen. Over the next several years, Geronimo and his fellow warriors would wage attacks on the Mexican people. The leader later recalled, “In all the battle I thought of my murdered mother, wife, and babies…and I fought with fury.” He wore his hair short for the remainder of his life, a sign of mourning among many Indigenous groups.

3. He Wrote an Autobiography

In his later years, when he was living as a prisoner of war, Geronimo wrote an autobiography. The manuscript was transcribed and edited by Steven Melvil Barrett, who was a colonel in the US Army, superintendent of Oklahoma schools, and notable author. Geronimo’s Story of His Life was published in 1906 and provides a first-person account of his days. The book includes details such as the Apache creation story, his childhood, and his retelling of the numerous conflicts he was involved in against other tribes, Mexico, and the United States.

Geronimo dedicated his book to President Theodore Roosevelt, with the words, “I am thankful that the President of the United States has given me permission to tell my story. I hope that he and those in authority under him will read my story and judge whether my people have been rightly treated.” Roosevelt and Geronimo had a tense relationship. Though the Apache leader had ridden in Roosevelt’s inaugural parade along with several other Indigenous chiefs, the president had declined his request that the government consider allowing the Chiricuaha to return to their homelands. The meeting, which was documented in the New York Tribune, quoted Roosevelt as saying, “We must wait a while before we can think of sending you back to Arizona.”

4. Almost a Quarter of the US Army Hunted Him

As the 19th century progressed and the US idea of Manifest Destiny continued to spread, Geronimo and his people faced off with the US army in an effort to retain their freedom and homelands. The Apache fought the US in one of the longest conflicts between an Indigenous group and the US government, lasting 24 years from the mid-1800s onwards.

In 1874, the Chiricahua Apache community was moved to a reservation in San Carlos, Arizona. Geronimo would leave reservation life with various groups of followers on many occasions. He was arrested multiple times but was undeterred. In 1886, Geronimo escaped custody again, leading a small group of fewer than forty followers. Five thousand US soldiers, approximately a quarter of the entire army at the time, were sent after the small group, accompanied by 500 Indigenous auxiliary fighters. Mexico also deployed three thousand soldiers and several hundred volunteers, and a $25,000 bounty was placed on Geronimo’s head. Geronimo eventually surrendered at the end of the summer when army officials threatened to send the remaining reservation Chiricahua to a Florida prison.

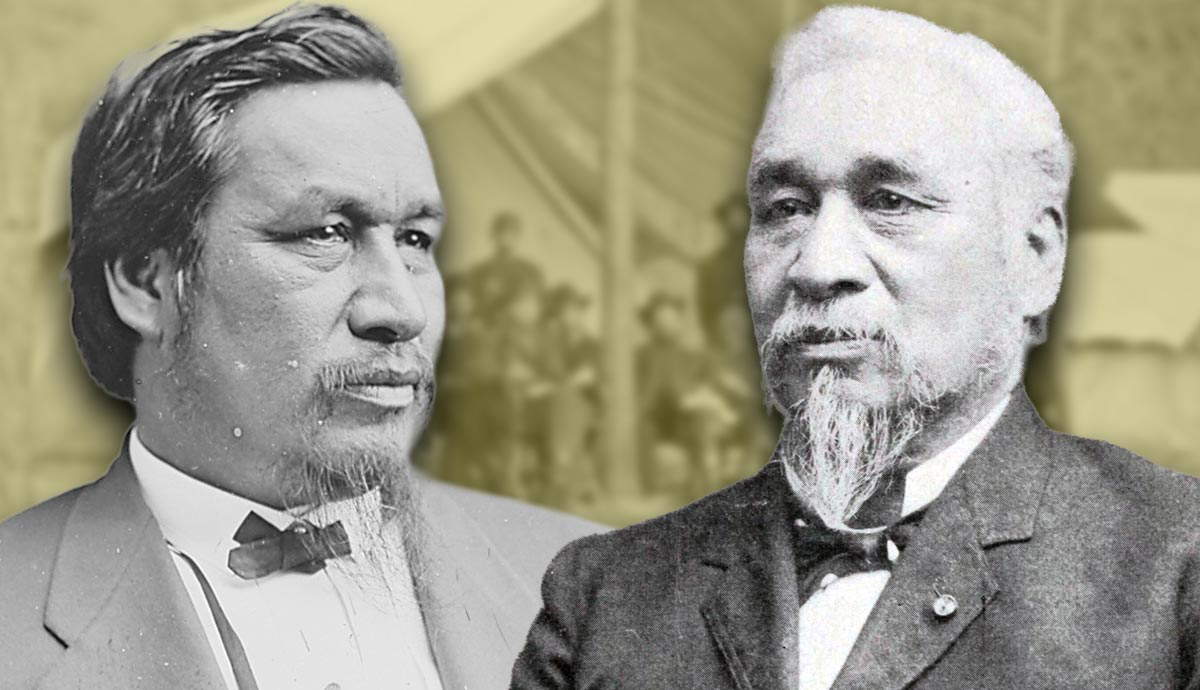

5. He Attended the 1904 World’s Fair

Geronimo attended the World’s Fair, formally known as the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, in St. Louis, Missouri, with permission from President Theodore Roosevelt. Branded “The Apache Terror,” Geronimo was featured alongside other Indigenous celebrities such as Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce and Quanah Parker of the Comanche. The men were part of the “human zoo” at the exposition. Geronimo spent his summer signing autographs for white attendees and participating in reenactments.

6. He Spent Over 20 Years as a POW

While his early life was spent constantly on the move, his later years were spent in confinement. After his formal surrender to US General George Crook in the summer of 1886, Geronimo was arrested and held as a prisoner of war. He spent over two decades as a prisoner of the United States, being held at prisons in Florida and Alabama, before spending the last 14 years of his life at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

In his first prison residence at Fort Marion in Florida, Geronimo was held with 501 other Apache prisoners who had been transported by train from the Southwest. The prison was designed to hold only 150 prisoners. After a brief period in Alabama after Fort Marion, the Apache prisoners were transferred to Fort Sill in 1894. They were the last Indigenous group to be transferred to Oklahoma’s “Indian Territory” after relocation efforts began in 1830. Geronimo died in February 1909 from pneumonia. On his deathbed, he stated, “I should never have surrendered.”

7. The US Military Used Geronimo as a Code Name

Geronimo’s legacy has been preserved in history books, photographs, novels, and in people yelling, “Geronimo!” when they take literal leaps of faith. However, his memory has been preserved by his former enemy, the United States military, in another way. “Geronimo” was the code name used for the operation to kill al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, the mastermind behind the 9/11 attacks. When Bin Laden was located and killed in 2011, the first message reporting the death to President Obama read “Geronimo-E KIA” (Enemy Killed in Action). Two teams of Navy SEALS participated in the successful operation, which was formally known as Operation Neptune Spear.

There was some controversy over the use of Geronimo’s name in this context. Some believed the designation referred to Bin Laden himself and found it offensive that Geronomio would be compared to a terrorist. Some, including Geronimo’s great-grandson Harlyn Geronimo, a US military veteran, called for an apology from the White House. None was ever extended.