For centuries, studies of human anatomy inspired progress in art, and famous artists took part in recording and coding anatomic knowledge. Studies of anatomy were reflected in art in various forms, from wooden acupuncture models meant as study manuals to large-scale oil paintings and works containing social commentary and the exploration of the hidden biases of medicine and science. Read on to learn more about the use of anatomy in art.

Famous Artists and Anatomy: Renaissance Wax Models

In the Antiquity and the Middle Ages, studies of human anatomy were severely limited by religious and moral limitations that did not allow them to work with deceased humans or to dissect their bodies. For that reason, knowledge was limited to external observation and occasional trauma-caused interventions. Certainly, there were those who dared to break the rules and move science forward, yet their practice was frowned upon.

The radical change happened in the Renaissance era. Compared to the Medieval paradigm, which put God and faith in the center of the universe, Renaissance thinking was centered around humans as God’s creations. Studies of the natural world and scientific experiments were encouraged, and dissections of animals and humans were regarded as necessary to society. Of course, not all humans were seen as science manuals. Scientists performed dissections only on the bodies of executed criminals, thus both fulfilling their needs and prolonging the cadaver’s punishment in the eyes of the public.

Still, the execution rate did not keep up with the needs of doctors and medical students. For that reason, medical practitioners began searching for new methods to either preserve or replicate human body parts. Initially, they commissioned artists to create wooden carvings of dissected organs, inspired by the Catholic tradition of saints’ sculptures. However, the texture and weight of wood had little in common with real human bodies. As an alternative, artists came up with the idea of using painted wax that was soft and reacted to touch.

These wax figures had opening chests and stomachs and organs that could be taken out to be studied. Despite their original intended function, they were not just scientific objects. Often, artists aimed to create beautiful sculptures rather than just study manuals: they adorned them with pearls, human hair wigs, and blue glass eyes. Perhaps, this was required to at least partially aestheticize the gruesome routine of medical practice.

Renaissance & Baroque Painting: Caravaggio Rembrandt’s Body Paintings

Even those artists who did not work for medical universities studied anatomy on real subjects. It was common for artists to attend dissections and make sketches during them. Many artists, including Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, dissected bodies themselves. Thus, the images of bodies, tissue, wounds, and organs became increasingly more realistic in the art of that era.

In the Middle Ages, depictions of Christ’s wounds were mostly schematic, indicating trauma rather than reproducing it. In Baroque art, Caravaggio and his contemporaries became painfully realistic, evoking physical responses of disgust and nausea. Painted scenes of martyrdom and torture sometimes became unbearable to watch as artists painted from reality and were directly aiming to shock.

Another Baroque master well familiar with human anatomy was Rembrandt van Rijn. The famous painting The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp was painted in 1632, when the Amsterdam Surgeons Guild, headed by Dr. Tulp, commissioned a group portrait. Rembrandt was a known master of such works, skillfully positioning large groups of people in a way that each of them remained recognizable and engaged in the composition. Two decades later, Rembrandt executed another anatomy lesson painting, this time graphically depicting dissection of the brain.

It is unclear if Rembrandt ever dissected bodies himself. Most likely, he studied anatomy through medical literature and attended dissections performed by others. Still, the painted scene did not follow the established rules of dissection, as Rembrandt left the cadaver’s stomach intact. In reality, all autopsies at the time began with the extraction of liver and spleen. Moreover, X-ray analysis has shown that the dissected left hand was a later addition to the painting. The original cadaver did not have a hand at all, as it was cut off as part of his punishment for robbery.

Japanese & Chinese Acupuncture Models

Similarly to the West, in China and Japan, dissection of human bodies was similarly forbidden. Yet, the oldest known anatomical atlases, known as Mawangdui Silk Texts, came from China and dated back to the 2nd and 3rd centuries BCE. These atlases represented human bodies in stylized non-realistic form but still were used in medical practice. Another distinctive form of art and anatomy fusion is the wooden sculptures found in Japan. These doll-sized figures were used as acupuncture manuals, marked with directions and spots to be treated with needles.

Surrealist Bodies: Blood and Terror

The 20th-century art of Surrealism, although relying on the fantastical imagery produced by human subconsciousness, frequently used anatomical motifs. For the Surrealists, the body was the vessel of eroticism, repressed desires, and traumas. Humans are well aware of their physicality but often choose to ignore it, too frightened to think to succumb to the primordial physical side of their existence. As a result, images of body parts and their mutilations often occurred in Surrealist’s work.

The most obvious and disturbing example was, for sure, the close-up scene of an eye cut with a razor from Salvador Dali and Luis Buñuel’s film An Andalusian Dog. There were, however, less shocking occasions. Surrealist assemblage artist Meret Oppenheim decorated gloves with patterns of veins and arteries, toying with the concepts of covering and revealing, the inner and the outer. Rene Magritte featured the pattern of blood vessels and skinned bodies in his experimental work The Blood of the World.

Jean-Michel Basquiat & “Gray’s Anatomy”

The famous Neo-Expressionist Jean-Michel Basquiat never studied anatomy as a scientific discipline beyond basic school requirements but nonetheless had an unusual interest in it. At the age of seven, he was hit by a car while playing outside and had to go through a series of surgeries, including spleen removal. While Basquiat was confined to bed, his mother, who championed his interest in art from an early age, brought him a copy of Gray’s Anatomy, a Victorian-era illustrated anatomy atlas. From that moment, Basquiat became obsessed with the human body and with the way it was coded in literature. In his later paintings, he would incorporate small drawings of spines, pelvises, and skulls into larger compositions, manipulating various forms of passing information—atlases, commercials, cartoons, graffiti, and many more.

Marc Quinn’s Blood Portraits

Over the centuries, blood was often included in the subject matter of artistic works, but it was rarely an artistic tool in itself. British contemporary artist Marc Quinn changed that by creating one of the most controversial artistic projects of all time. Since 1991, every five years, Quinn has created a silicone mold of his head, filled it with his own blood, and frozen it, turning the liquid into an ice sculpture. Thus, Quinn creates a self-portrait not only in an artistic but also in a medical sense, documenting processes unfolding both outside and inside his body.

Anatomy in Contemporary Art: Famous Artists Rethinking Human Bodies

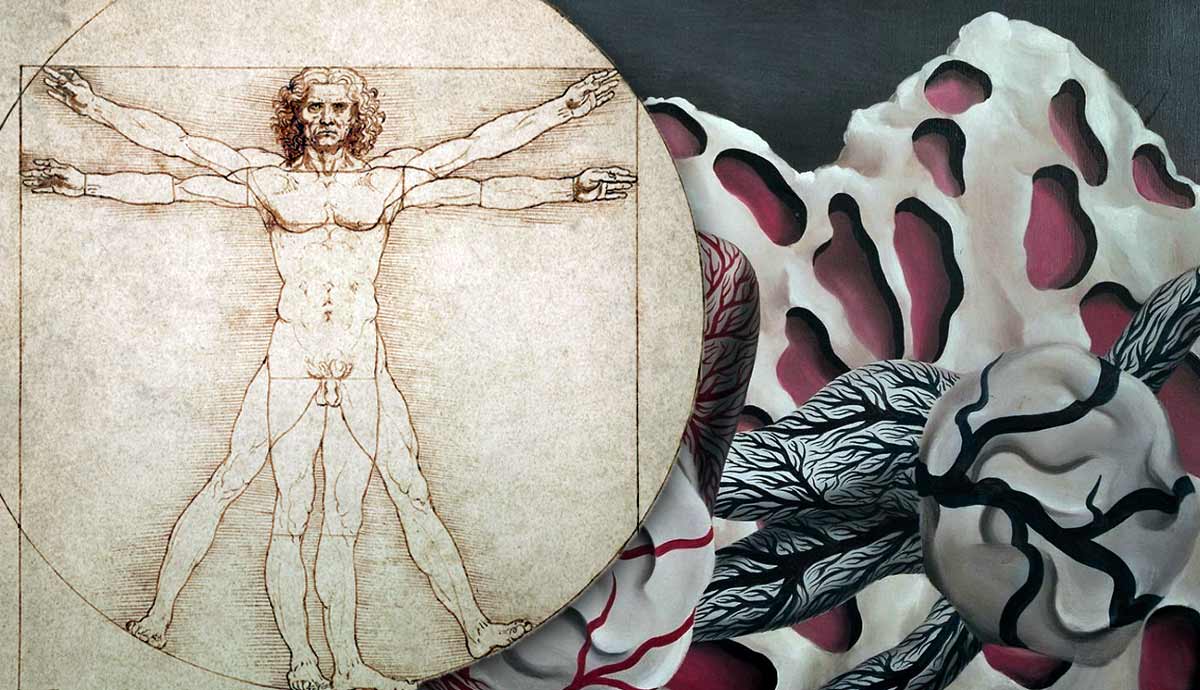

While studying old anatomical atlases, contemporary artists and thinkers often note that these books propagate only one type of body and condition, dictated as the universal standard. Taking a white, male, abled body as a reference model, authors of anatomy books from the past automatically pathologized all differences related to sex, race, and individual conditions. This was particularly evident in relation to the studies of Indigenous peoples of colonized lands in Africa and America.

In the early 2000s, contemporary artist Wangechi Mutu began employing images from Victorian atlases on female anatomy, contemporary fashion magazines, and pornographic materials to explore the relationship between health and illness, beauty and ugliness, desire and repulsion, and white and Black bodies. For her, all these images mark the position of a particular body type (in her case, a Black female body) in a particular culture and specific moment in history. Among other things, Mutu’s works ruin the myth of the seeming objectivity of science and medicine, unfolding the embedded bias and oppression.