Anyone who’s spent any measurable amount of time with a child can probably tell you first hand… they’re all wild. Particularly those children between one and three years of age. And if you’re raising teenage boys, you know the absolute feralness and unpredictability of human youth.

There have been circumstances in which kids, with no parents in sight, have simply walked out of the woods and into towns where civility and etiquette rule. For many of these children, the constraints of conformity were just too much and they either didn’t make it or didn’t learn to behave as a member of society. Take a closer look at the stories of wild children and those raised by animals. Meet history’s feral children.

1. Victor of Aveyron: The Original Wild Child

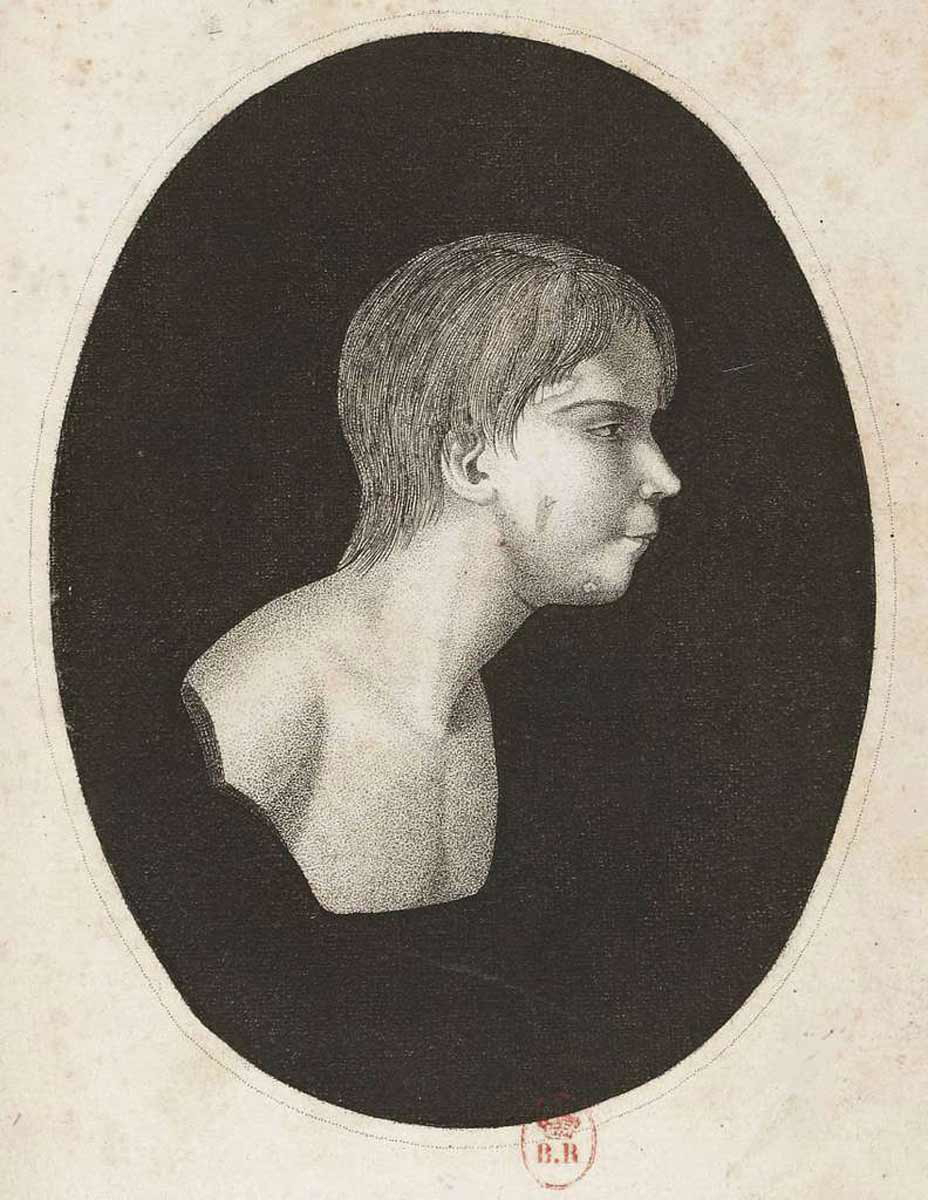

Enter Victor of Aveyron, the original feral child, who literally wandered out of the woods of France in 1800 and into the annals of history, sparking pity and fascination, and beginning the study of special education.

Victor’s story starts in a thicket near Aveyron, France, where he was found frolicking like a pint-sized Tarzan, completely naked, filthy, and covered in scars. Imagine the villagers’ surprise when this twelve-year-old boy (that is an estimate since Victor’s parents were never identified and his birthdate remained unknowable)—who had clearly missed out on a few lessons in social etiquette—suddenly appeared in their midst. He had zero interest in clothes, refused to be touched, and had a temper like a cat getting a bath. The overarching belief was that Victor’s early years were spent in total isolation, his behaviors more squirrel than human.

The authorities, being authorities, had no idea what to do with him. They first labeled him an “imbecile,” a term used for anyone who didn’t fit their idea of a proper human. That is when a young physician named Jean-Marc Gaspard Itard saw potential and intervened. He saw Victor’s predicament as an opportunity for experimentation and documentation concerning human development. Itard gave the wild boy the name “Victor” and embarked on a six-year experiment to see what this child raised by nature could learn.

However, there was no heartwarming montage of Victor becoming a well-mannered young man. Itard became convinced that Victor was a normal child, perhaps a bit rambunctious, that irresponsible alcoholic parents had dumped in the woods. It wasn’t quite The Miracle Worker. Itard managed to get him to wear clothes and stop snarling at people eventually, but teaching him to speak was a whole different beast. Victor was all ears for the sound of a cracking walnut—his favorite snack—but the spoken word? Not so much.

The good doctor did his best to teach Victor words and concepts and even got him to react to a few basic commands. Yet, as much as Itard tried, Victor never quite grasped language the way most of us do. It was as if his brain’s language center had a “Closed for Business” sign-up, a phenomenon that modern scientists think could have been due to a critical developmental window closing before he had the kind of exposure that would allow this skill to grow.

There has been a lot of speculation over the years about what exactly made Victor the way he was. Some experts, Uta Frith for example, have suggested he might have been autistic, which could explain his intense focus on certain stimuli (like that crack of a walnut) and his complete disinterest in relating to people. Others think his case demonstrates just how crucial early human interaction is for development—miss the boat on that one, and, the end result is a being that understands what it takes to survive (water, food, and a place to sleep) but not the means to communicate or express deeper emotion.

Despite Itard’s best efforts, Victor never learned to speak beyond a few basic words and sounds. He did, however, show some signs of empathy, which Itard took as a major step in his development. The scientist thought teaching a boy who grew up in the wild that other humans have feelings too was no small feat.

The story of Victor of Aveyron is both tragic and intriguing, a testament to the unplumbed depths of the human mind and the challenges of trying to socialize someone who, for all intents and purposes, was more attuned to the rhythms of the forest than to those of Parisian society. Itard may not have been able to turn Victor into a princely model of gentlemanly behavior, but his work paved the way for our modern understanding of human development and the irrefutable importance of early childhood education.

Victor lived out the rest of his days with Madame Guenn, a kindly woman who took him in while Itard worked with the boy. Victor passed away around the age of 40, never having fully joined the world of men, but forever remembered as the boy who walked out of the woods and made the world question what it means to be human.

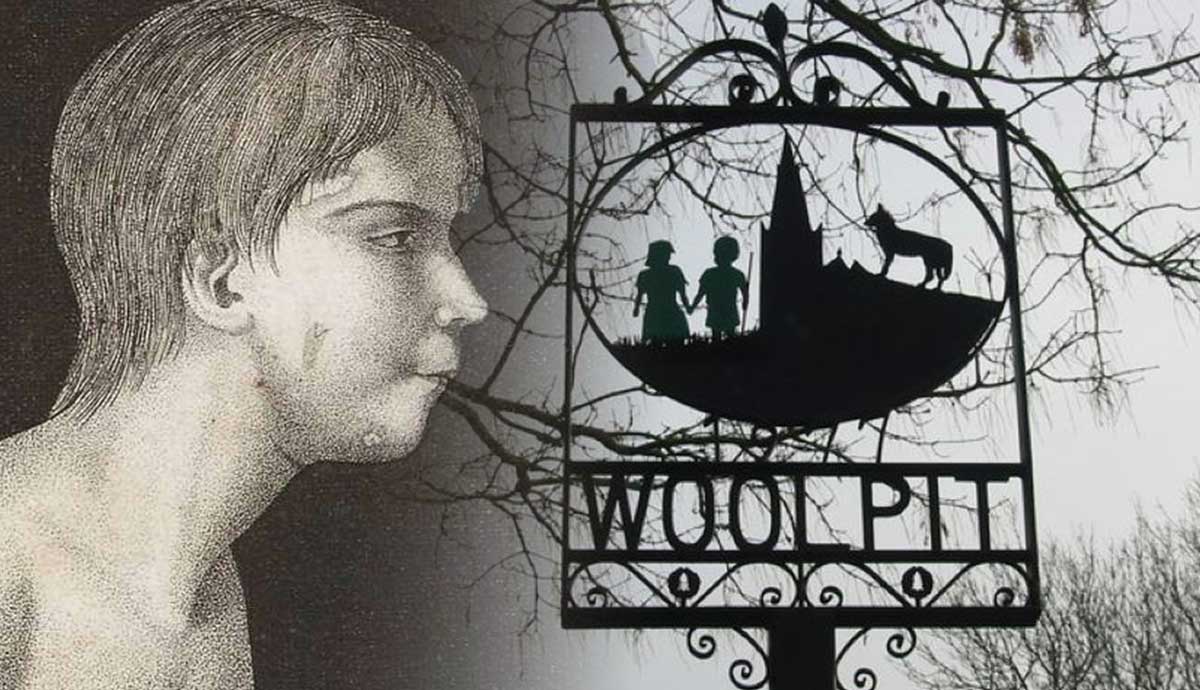

2. The Green Children of Woolpit

One of the most whimsical and puzzling tales of feral children is the story of the Green Children of Woolpit. The children weren’t pink and round or pale and starving. They. Were. Green. Not your average forest wanderers, these two siblings practically strolled out of the 12th-century equivalent of a sci-fi novel.

Sometime during King Stephen’s reign (1135-1154), villagers in Woolpit, Suffolk, stumbled upon a boy and girl near an old trap for wolves. The boy and girl seemed pretty ordinary—except for their strange clothes, an alien-like language, and the fact that they were green. The kids were promptly taken to the home of a local landowner, Sir Richard de Calne, who must have been wondering if he was still asleep and dreaming.

The children at first refused all food but raw beans, even going so far as to pluck them straight from the fields they were growing in. Slowly, Sir Richard had success in increasing their dietary options. After a while, their green skin faded, and they started to adjust to village life. Unfortunately, the boy didn’t live long, passing away shortly after being baptized. His sister, however, stuck around long enough to learn English and reveal where they came from.

According to William of Newburgh, a monk who documented the children’s seemingly otherworldly story, the girl claimed they were from “St. Martin’s Land,” a place of perpetual twilight where everything was misty and green. She didn’t know how they got to Woolpit. Her claim was that one minute they were herding their father’s cattle; the next, they were hearing church bells and wandering out of a cave. So were these kids changelings from a fairy realm, victims of alien abduction, or just really lost? There are several theories.

The most likely guess is that the children were actually Flemish orphans who got separated during a massacre in nearby Bury St. Edmunds. Flemish immigrants weren’t exactly popular at the time (there were massacres of the “outsiders”), and it is possible that the villagers’ shock and confusion at their foreign clothes and language turned into the story of a mystical green land. The twilight and cave aspects could be explained if the kids were hiding in the dense forest or, more dramatically, escaping a mine.

Or, perhaps having taken the children in, the villagers made up the fairy story in order to protect the young ones from those who would harm them. If so, the rewriting of their story worked. The girl grew up, worked for the man who cared for her and her brother, and eventually married a man from the village. Together, the story goes they had at least one child.

What about that weird green skin? Some say it could have been due to a severe diet deficiency, like chlorosis, or even arsenic poisoning. A rumor, unsubstantiated, was that the children had belonged to a local noble who didn’t want responsibility for them. There’s also a less magical but very medieval explanation that these kids, maybe covered in a plant stain or suffering from malnutrition, got mixed up with folklore and exaggerated retellings over the centuries.

Whatever the truth, the Green Children of Woolpit remains a fascinating, mysterious footnote in history, an age-old “What on earth…?” moment that keeps us wondering.

3. Dina Sanichar: The Original Jungle Boy

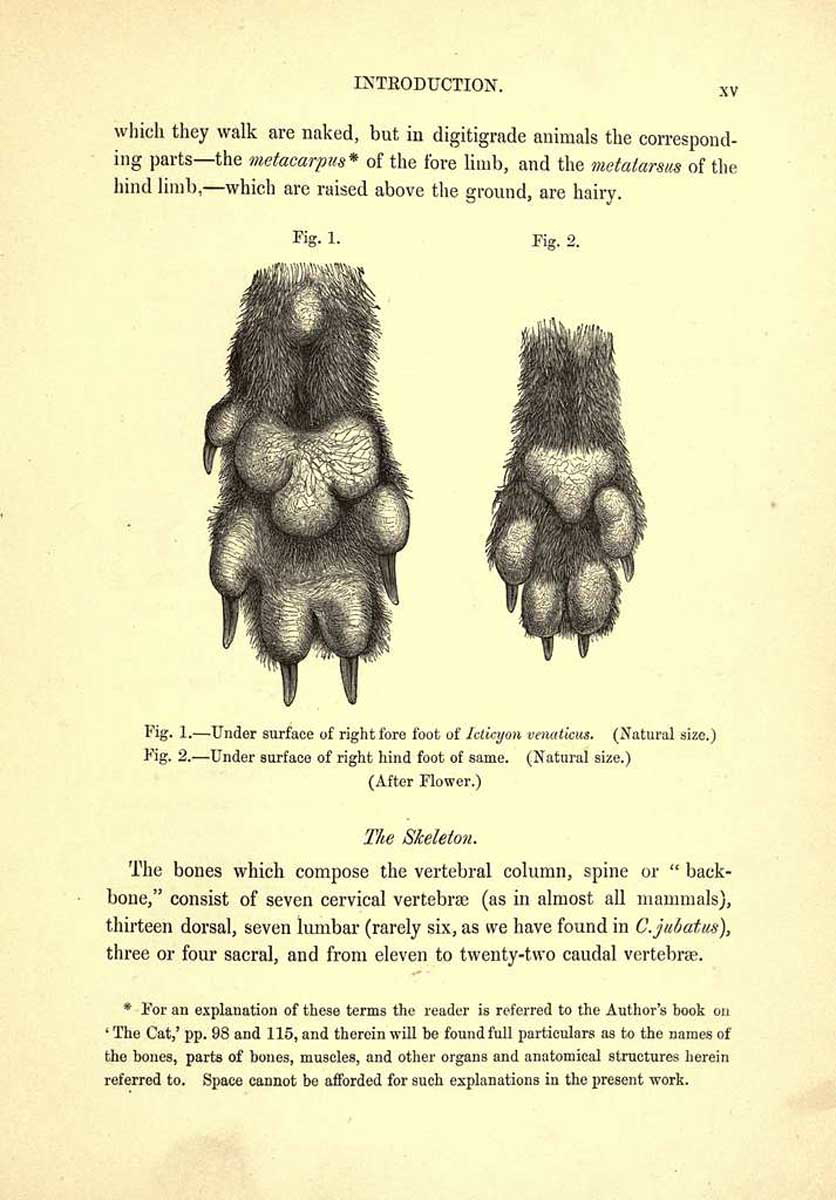

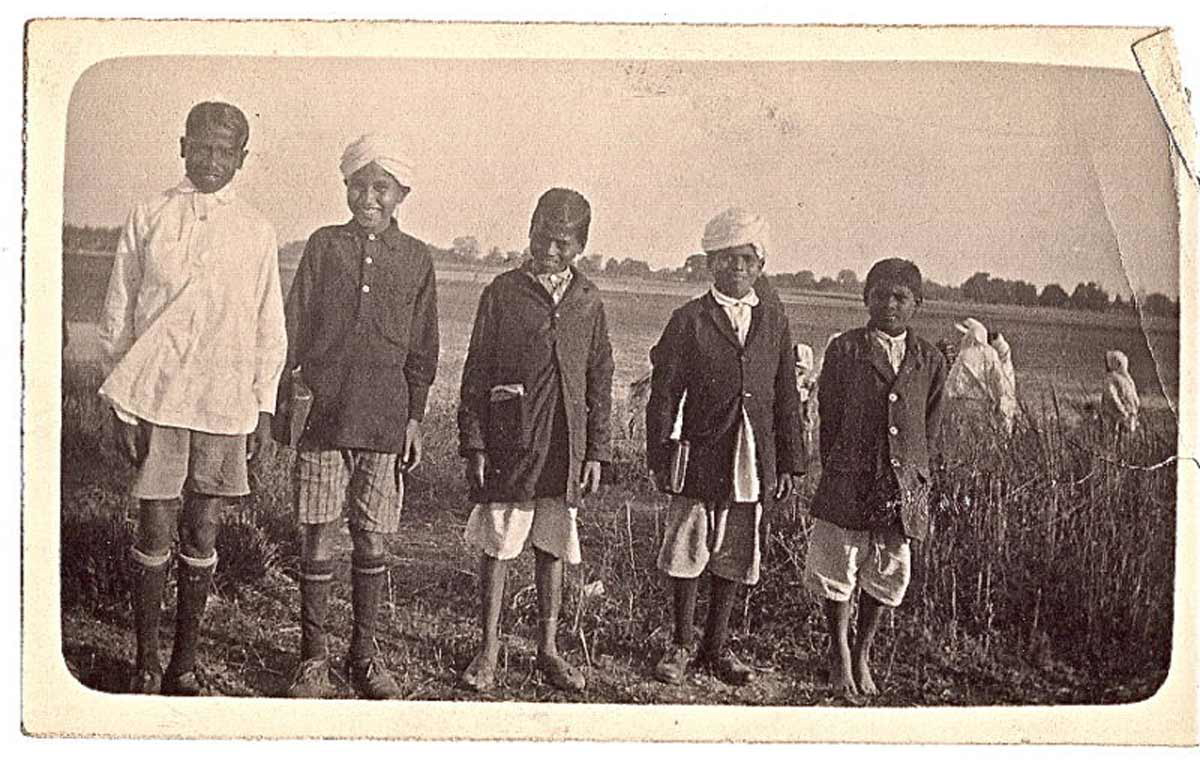

Before Disney turned The Jungle Book into a catchy musical romp, there was Dina Sanichar, the pack-raised “wolf boy” of India. Discovered by hunters in 1866, Dina was about eight years old when they found him, not exactly skipping through the jungle, but holed up in a wolf den in a cave in Bulandshahr, Uttar Pradesh. His life story, however, was far from the singing bear and friendly panther Kipling conjured up for readers.

Dragged from his lupine family and dropped into human society, Dina was sent to the Sikandra orphanage in 1867. What followed was a bizarre, oddly documented 20-year struggle to adapt to civilization. It turns out, learning to walk upright and wear clothes after spending one’s formative years literally running with wolves isn’t as easy as pie. Dina never learned to speak and had a particular fondness for gnawing on raw meat—something the orphanage wasn’t too thrilled about.

There is a problem, however: Dina’s story might be an amalgamation of more than one feral child. The orphanage admitted to caring for at least two boys raised by wolves, though the first didn’t last long, dying just a few months after his arrival. Dina, on the other hand, lived much longer—about two decades—during which he adopted some human habits, like begrudgingly wearing clothes. He also developed a full-blown nicotine addiction, picking up smoking at some point during his stay at the orphanage. While he never quite mastered the whole walking bipedally schtick, Dina apparently had no problem with cigarettes.

He tragically succumbed to tuberculosis, a rather mundane end for a boy who had survived life among wolves. Though some say Dina’s story inspired Kipling’s Mowgli, it is unclear if Kipling even knew about him. He had a habit of pulling inspiration from multiple sources, and with the orphanage’s admission of having cared for more than one “wolf child,” it is likely that Dina’s story is just one piece of a larger, messier puzzle.

Regardless, the story of Dina Sanichar offers a glimpse into the struggle between the raw freedom of nature and the manmade constraints of human society. Dina’s tragic end reminds us that the wild isn’t always the dangerous part—it is sometimes the human world that proves to be full of vice.

4. Marina Chapman: The Girl Who Lived With Monkeys

Marina Chapman’s childhood wasn’t just a rough start—it was a survival story straight out of a Victorian adventure novel, complete with a troop of capuchin monkeys. At the age of five, Marina was kidnapped from her Colombian village only to be abandoned alone deep in the untouched jungle. Two days in, half-starved and terrified, she stumbled upon a group of capuchins. However, they didn’t accept her with open arms like some kind of wild interspecies adoption story.

Marina, acting purely on instinct, did what any resourceful child might do when surrounded by monkeys: she tried to fit in. She ate what they ate, drank what they drank, and gradually learned to move like them. Over five years, she became completely feral, losing her spoken language, her human habits, and nearly her identity. Yet she found a kind of acceptance, even a sense of belonging, within this unlikely simian family.

For a long time, the animals just ignored the small child in their midst. Then, they tolerated her presence more than anything else. Bit by bit, there were key moments of connection. Once, after Marina suffered from severe food poisoning, an elderly monkey—whom she now calls “Grandpa”—led her to some muddy water. After drinking it and vomiting, she began to recover. This moment of care marked a shift in Marina’s world: the monkeys, especially the younger ones, started to include her in their daily activities. She learned to climb trees, find safe food, and even discovered that if she stood under them as they carried bananas, she could recover any that fell.

Marina has her skeptics. Her story is almost too incredible to believe, and it certainly stretches the boundaries of what we think we know about memory, survival, and the relations between species. How could she remember so vividly a time in the jungle if she had blocked out her earlier years? How could she remember “Grandpa” but not her real parents? Some have wondered if her mind crafted these memories as a coping mechanism, a way to make sense of a traumatic and violent childhood. Others point out that she has never been able to locate the exact part of the jungle where she lived, raising questions about whether the whole experience is based in fact.

Marina herself has no doubt, nor do her daughters and husband living with her in Britain. The capuchins, known for their sometimes friendly nature toward humans, kept her alive when she had no one else. They didn’t love her in the human sense, but they offered a strange, wild form of companionship. She recalls the first time a young monkey landed on her shoulders, the sensation of those tiny hands on her face—a touch that meant she had found a place where she could eat and sleep safely.

Today, Marina’s story is both a testament to her resilience and a reflection on the kindness of animals in contrast to human cruelty. Whether or not her memories are entirely accurate, her survival against all odds is a remarkable tale. It also reminds us that sometimes, in the face of unimaginable hardship, help comes from the least likely direction.