For centuries, women were discouraged from practicing art professionally. Thinkers of the Renaissance and Modernity believed that women lacked the clarity of mind or a certain creative spirit that would provide them with artistic merit. Still, despite all the challenges, many women painters tried and succeeded and even left lasting marks with their work. Here are 8 famous women painters you need to know.

1. Sofonisba Anguissola (1532–1625)

Sofonisba Anguissola was one of the most famous and successful women painters of Renaissance Italy. Most women present and appreciated on the Renaissance art scene were patrons or commissioners. They played important roles in funding and often designing the works, coming up with detailed plots and compositions for artists, but were never credited as someone who actually had a hand in artistic production. Sofonisba Anguissola was a happy exception. A child of a noble yet poor family, she was encouraged to study and practice arts by her father. Out of seven Anguissola siblings, four, all of them girls, became painters.

At the age of 22, Anguissola met Michelangelo, who recognized her talent and offered to give the young painter some instructions. As a woman artist, Sofonisba Anguissola was not allowed to study the human body and paint nude models, so she chose to experiment with the portrait genre. Self-portraits were a significant part of her artistic oeuvre, marking her confidence as a professional painter.

2. Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1653)

Artemisia Gentileschi was one of the greatest painters of the Baroque era. Like many of her female colleagues, she was lucky enough to be born into an artistic family, which allowed her to get basic training at home. Artemisia’s father, Orazio Gentileschi, started his career as a Mannerist painter but soon fell under the influence of Caravaggio and his style. He passed this particularly dramatic way of painting, with radical contrasts and dark backgrounds, to all of his children, of whom Artemisia was the most talented. Apart from her native Rome, she worked in Florence and Venice, and even spent several years in England, working at Charles I’s court.

Gentileschi personally knew Sofonisba Anguissola and appreciated her work. Although the two artists were stylistically and conceptually different, both of them reflected the unsettling realities of women artists’ experiences at their times in the works, albeit not always intentionally. One of the most prominent motifs of Gentileschi’s work was the subject of female rage and revenge, often expressed in retaliation for a sexual assault. Such a difficult and dramatic subject matter was the result of Gentileschi’s own traumatic experience.

3. Clara Peeters (1589–unknown)

Clara Peeters was a rare woman painter who worked in Antwerp in the early decades of the 17th century. Unfortunately, art historians still do not know much about her life and work. Even the date of her death remains a mystery, as does the way she managed to build a career at a time when painters’ guilds did not grant membership to women. In Peeters’ time in Antwerp, guild membership was necessary to sell one’s work and receive commissions.

Peeters specialized in still-life painting, particularly, in mouth-watering compositions with food. Painting from arranged compositions, she often incorporated small self-portraits in the form of reflections on metal cutlery or wine jugs. Most art historians believe that Clara Peeters was one of the forerunners of the Dutch still-life genre.

4. Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899)

Immensely rich and successful, Rosa Bonheur was an outstandingly well-known animal painter. Raised by a father who believed in equal educational rights for men and women, she received the best artistic training possible. Unlike many other women painters, Bonheur was not content with painting domestic scenes and flower arrangements. To support Rosa’s interest in studying animals, her father rented a separate apartment in which he kept a menagerie of small animals. Years later, Bonheur would keep live lions and gazelles in her chateau. To visit farms and cattle markets safely, Bonheur had to apply for a special permit that granted her the legal right to wear men’s attire. That way, she could avoid unwanted attention and more easily blend in with her surroundings.

5. Suzanne Valadon (1865–1938)

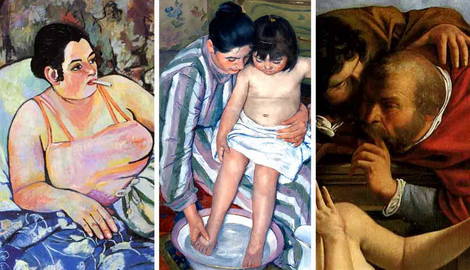

For centuries, the image of a nude female body in the history of art was intrinsically connected with male desire, or it acted as an allegorical symbol. The paintings of Edouard Manet and the Realist works of Gustave Courbet were not received well because they represented real women of their generation, often with explicit displays of sexuality. Still, there was little room for women’s voices in these systems.

Self-taught artist Suzanne Valadon changed that. Before turning to painting, she was a trapeze artist who injured her back during a rehearsal and was unable to continue performing. To support herself and her young son, Valadon became an artist’s model. While posing, she observed the movement of brushes and pens and soon developed her own artistic style. Her female figures, although often nude, were warm and empathetic, with models’ agencies and personalities still present. Valadon was the most commercially successful woman artist of her generation, who rose to great fame and immense wealth despite her initial poverty.

6. Hilma af Klint (1862–1944)

Hilma af Klint was trained as a botanical illustrator and a portraitist. The Swedish artist was a devoted spiritualist who experimented with automatic drawing and created images “dictated” to her by some Higher Power. Although she did not regard her spiritual work as artistic per se, she was the first known Western artist to begin working with purely abstract art, devoid of any material subject matter. The images in her works represented the evolution of spirit and products of spiritual consciousness.

For years, Hilma af Klint strived to understand her own work. Although she tried to grasp control over her painting, the will of the spirits was stronger. According to af Klint’s diaries, the spirits commanded her to build a spiral-shaped Temple that would bring spiritual knowledge to the human world. Although the project was never completed, the artist’s archive preserved blueprints and plans for the structure.

7. Mary Cassatt (1844–1926)

American painter Mary Cassatt spent most of her life in France, where she became a famous and respected member of the Impressionist movement. She was a close friend of Edgar Degas but broke off their friendship after a series of his anti-Semitic and misogynistic comments. Cassatt received her education in both the USA and France. Her parents were against her occupation of choice, but mostly due to the fact that Cassatt’s painting circle mostly shared feminist ideas.

Impressionism was a highly gendered movement. One of its most prominent topics was French urban life with its boulevards, cafes, and cabarets. For a respectable woman like Cassatt, these locations were off-limits. Back then, women were almost completely confined to the privacy of their homes, and could not appear in public unchaperoned. For Cassatt as an artist, this meant she could not paint outdoors or visit the same locations as her male colleagues. For that reason, she focused on topics that were in her immediate vicinity: emotional ties of mothers and children, domestic scenes, and socially acceptable leisure activities like reading or boating. Despite her emotionally charged works that depicted motherhood, she ardently rejected the possible roles of a wife or a mother herself.

8. Leonora Carrington (1917–2011)

Just like with many other famous art movements, within the Surrealist art circle, the voices of women artists were often unjustly ignored. In the shadow of self-proclaimed titans like Salvador Dali or Max Ernst, women Surrealists developed their own artistic language and system of symbols. Leonora Carrington was one such painter, who worked in close proximity and collaboration with other women. Although she was born in England, she truly demonstrated her artistic skill only after fleeing to Mexico to escape the grasp of her abusive family and the dangers of World War II. In Mexico, Carrington developed a friendship with another Surrealist painter, Remedios Varo, who greatly influenced her work. Carrington’s work relied on her subjective experiences and expressed her own mythology, sexuality, and trauma. In terms of visual style, she combined the influences of Hieronymus Bosch, Mexican folklore, and Western mysticism.