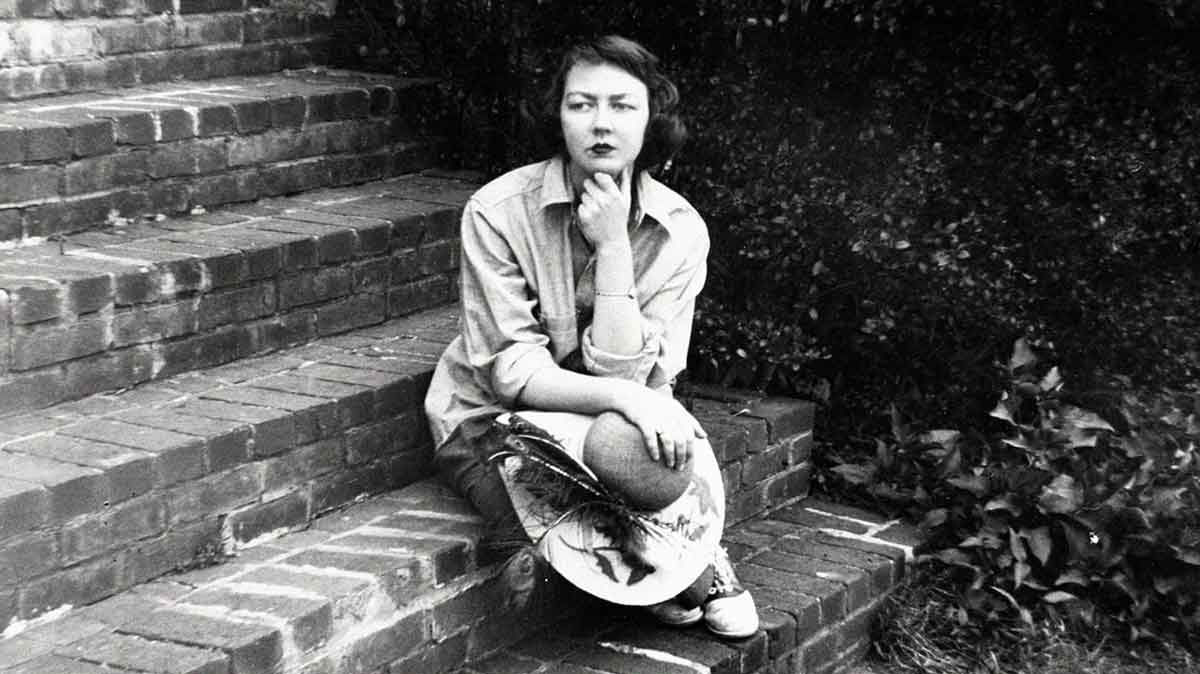

Southern Gothic writer, Flannery O’Connor devoutly believed in Christianity. Interestingly, however, references to French thinkers are scattered throughout several of her works. We will focus on her short story Good Country People and her novel The Violent Bear It Away. These works, as well as many of her letters, show that she was thinking about French philosophy and engaging with it in subtle ways.

Who Was Flannery O’Connor?

Born in 1925, Flannery O’Connor spent most of her life in Georgia. A devout Catholic, she was in the religious minority in a mostly Protestant South of the United States. This gave her, in part, a unique opportunity to critique negative aspects of the Protestant Christian faith, while still maintaining her belief in God and Jesus.

Always a gifted writer, she became one of the most famous American short story writers of all time. She forged into the Southern Gothic genre, creating compelling scenarios that questioned everything from hypocrisy to racial stereotyping, to mainstream evangelicalism.

Unfortunately, she also suffered from lupus for years. Especially towards the end of her life, this disease greatly impacted her ability to continue writing. In 1964, she died at only 39, leaving at least one novel unfinished, having already staked her ground in the history of American fiction.

What is Southern Gothic Literature?

Southern Gothic literature is a unique export of the American Southern literary scene. Stemming from the Gothic literary tradition in general, it still distinctly deals with the idiosyncrasies of the American South.

Often agrarian and colloquial, Southern Gothic literature showcases the seedy aspects of human life, the dark capacities of human individuals, and the “grotesque,” a word adopted by the genre. The “grotesque,” while keeping its literal meaning of distorted or disgusting, also refers to the literary element in Southern Gothic that often forcefully confronts the reader with uncomfortable truths. Likewise, violence is often a trope in this type of literature. Like other well-established American Southern Gothic authors such as William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor created a corpus that explores and expands on this genre.

What Is Existential Philosophy?

For the purposes of this article, “existential” and “absurdist” philosophy are dealt with as the same, since they are in fact, quite related. Albert Camus disseminated the idea that life is meaningless, but that does not mean that life has to be a sad void of meaning. Rather, he challenges people to forge ahead, creating their own meaning in themselves and their own lives.

Another famous French existentialist, Jean-Paul Sartre, went a step further, focusing on how humans have to exercise their freedom in order to be free, and free to choose.

But before there was Sartre, there was Martin Heidegger. Attempting to both create and explain his understanding of “Being,” Heidegger used the term “dasein,” the form of being in which humans must exist, and our relationship to the existence of the universe. All these philosophies wrestle with what it means to be human and exist in this world.

Flannery O’Connor: The Violent Bear It Away

Arguably Flannery O’Connor’s best novel, The Violent Bear It Away covers the rough history of a dysfunctional family. This family consists of a religious fanatic great-uncle, a bitterly secular uncle, a recalcitrant nephew/orphan, and a developmentally disabled son, the happiest character out of any of them. Rayber is forced to take in his young nephew, Tarwater after their crazy old uncle dies. While Tarwater is an interesting character regarding religion, Rayber best illustrates how O’Connor engaged with European philosophy.

Just like a Camus character breaking tradition and trying to find his own way, Rayber rejects the religion of his great-uncle. He declares: “It’s the way I’ve chosen for myself. It’s the way you take as a result of being born again the natural way — through your own efforts. Your intelligence” (O’Connor, 1960, pg 451). Rayber “kept himself upright on a very narrow line between madness and emptiness, and when the time came for him to lose his balance, he intended to lurch toward emptiness and fall on the side of his choice” (O’Connor, 1960, pg 402). This “emptiness” is reminiscent of Sartre’s seminal work, Being and Nothingness.

In an individualistic act of self-agency that will ultimately be self-destructive, Rayber fulfills his own destiny—emptiness—getting what he dubiously wanted. When he realized that his son had been killed, he “stood waiting for the raging pain, the intolerable hurt that was his due, to begin, so that he could ignore it, but he continued to feel nothing. He stood light-headed at the window and it was not until he realized there would be no pain that he collapsed” (O’Connor, 1960, pg 456).

In his own attempt at self-agency, he robs himself of “his due” and must accept the emptiness that he had prepared for himself. In this way, O’Connor warns of the path Camus and Sartre purport, making one’s own meaning out of nothingness, in case that is all there is left.

Good Country People

In Good Country People, Mrs. Hopewell is incessantly exasperated by her daughter, whom she had named Joy. Joy has since renamed herself Hulga. Hulga went to college to study philosophy, but due to health complications, including a prosthetic wooden leg, is apparently unable to get a job and thus lives at home with Mrs. Hopewell and their kitchen help, Mrs. Freeman. One day, a traveling Bible salesman comes to their door. Disgusted, Hulga tries to enlighten him, but he ends up teaching her a lesson.

Mrs. Hopewell laments Hulga’s choice of philosophy, a choice that O’Connor ironically comments on. O’Connor writes, “The girl had taken the Ph.D. in philosophy and this left Mrs. Hopewell at a complete loss. You could say, ‘My daughter is a nurse,’ … you could not say, ‘My daughter is a philosopher.’ That was something that had ended with the Greeks and Romans” (O’Connor, 1960, pg 268).

Already from this quote, we can see how Flannery O’Connor is poking fun at philosophy (its students are unhelpful and unemployed) and also people who do not understand it at all (like Mrs. Hopewell who potentially undervalues education in general). However, O’Connor gets more direct. For instance, Hulga also will sometimes shout things completely out of context, like “Malebranche was right: we are not our own light!” (O’Connor, 1960, pg 268). Malebranche was another French philosopher, who preached about ideas and God.

O’Connor also directly quotes one of Heidegger’s books. Mrs. Hopewell “had picked up one of the books the girl had just put down and opening it at random, she read, ‘ … Nothing — how can it be for science anything but a horror and a phantasm? If science is right, then one thing stands firm: science wishes to know nothing of nothing. Such is after all the strictly scientific approach to Nothing. We know it by wishing to know nothing of Nothing.’ These words had been underlined with a blue pencil and they on Mrs. Hopewell like some evil incantation in gibberish” (O’Connor, 1960, pgs 268-269). Negatively affected by this “evil gibberish,” Mrs. Hopewell understands nothing about this passage. However, it shows how O’Connor was well-versed in philosophical readings.

Later in the story, the Bible salesman tricks Hulga. They discuss religion and philosophy as Hulga acts hoity-toity and boasts about not believing in God. But at the climax of the story, he lures her into a barn and takes off her prosthetic leg. He reveals that selling Bibles is a sham for scamming people and, moreover, that he only pretends to believe in God. Leaving with her leg, shamefully trapping her in the loft, he jeers, “You ain’t so smart. I been believing in nothing ever since I was born!” (O’Connor, 1960, pg 283). Again, in his call of “believing in nothing,” O’Connor intentionally echoes both Sartre and Heidegger’s beliefs.

Traces of Philosophy in O’Connor’s Letters

Aside from incorporating French philosophy into her fiction. Flannery O’Connor wrote several letters where she references knowing or having read about multiple thinkers. For instance, she told one pen pal: “[my old friend] has just sent me an article out of The Ave Maria, one of her favorites, about Camus. You reckon she spends her idle hours reading Camus? I doubt it” (1957). Her lighthearted disbelief that this acquaintance understands Camus points to how she herself understood enough of him to comment on it.

She writes to another friend: “Are you going to see Heidegger on his mountain top? Are you going to see Msgr. Guardini, Karl Adam, or Max Picard, or is Max Picard still living? What about Marcel and what about that lady critic that is so good — Claude Edmon Magny?” (1957). Listing off not only famous philosophers but even specific critics shows how well-versed she was. She mentions Heidegger again in an earlier letter: “Heidegger writes a great deal about the poet’s business being to name what is holy” (1954).

Flannery O’Connor is quoted as saying: “Never read Beauvoir. Never aim to,” which is delightfully ambiguous. Was O’Connor saying that she hadn’t read Simone de Beauvoir, or telling someone NOT to read her? But it is evident she knew enough about her to express ambivalence. She also comments on Beauvoir’s partner, Jean-Paul Sartre: “M. Sartre finds God emotionally unsatisfactory in the extreme” (1955).

What is evident is that Flannery O’Connor, despite having only studied in the American South and adhering to Roman Catholicism, was very well-learned about non-Catholic existential philosophy, among other kinds. She read their works, wrote about them in her letters, and let some of their ideas seep into her fiction. Whether or not all this reading of philosophy affected O’Connor’s true beliefs, is uncertain, but there is enough evidence to show how she was wrestling with these thinkers’ worldviews.

Bibliography

O’Connor, Flannery, Collected Works, edited by Sally Fitzgerald, The Library of America, 1988.