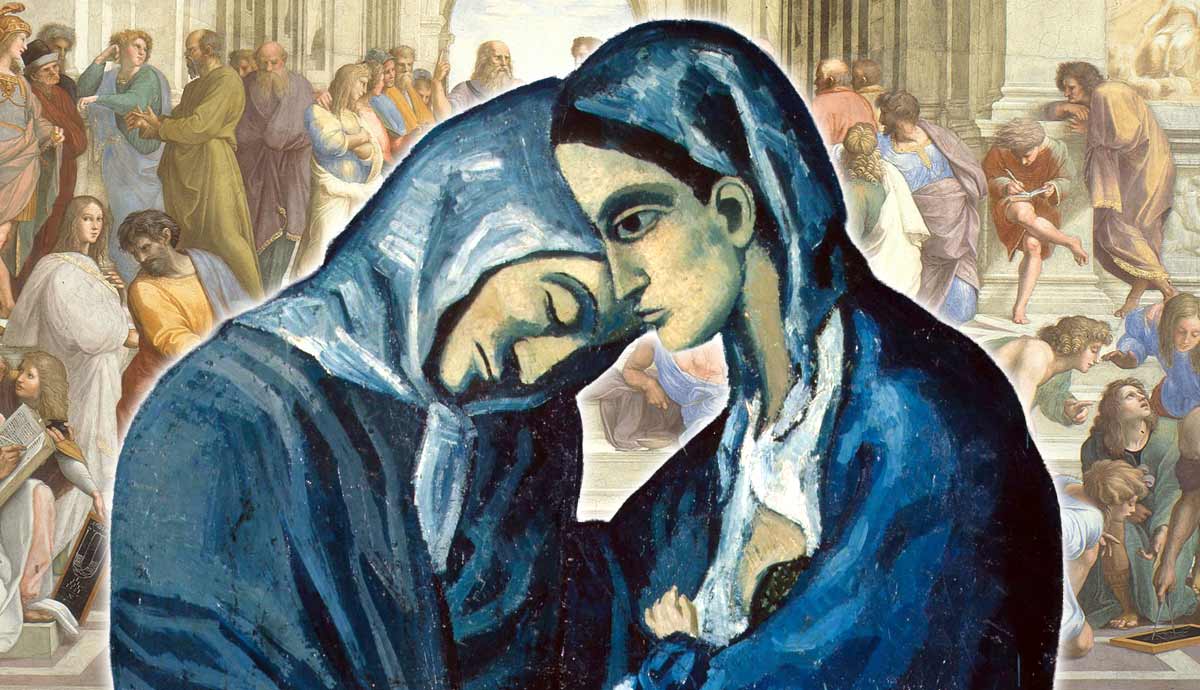

In Ancient Greek philosophy, friendship (or “philia”) was considered fundamental for shaping how one thought, acted, and organized society. However, we will see that thinkers like Plato, Aristotle, and Socrates viewed the matter rather differently from how we might today. Of course, they took an interest in personal relationships, as did other school movements, such as Epicureanism, founded by Epicurus, and Stoicism. But there is also something else going on: a sense in which being a friend can help you towards wisdom, ethical living, and even political harmony. Let’s explore.

Socratic Friendship: The Search for Truth Together

Socrates viewed friendship as more than just being friends; it was a way to find truth and wisdom. He thought that if people were true friends, they would use each other to grow their intellects. To him, having mates meant helping them become better individuals, both morally and philosophically, not simply hanging out together.

To bring his friends on board with this thinking, Socrates, whose friends must have been very patient with him, would ask lots of leading questions and challenge their answers. This became known as the Socratic method, a way of getting to the bottom of things through dialogue.

Because he reckoned nobody was ever genuinely wise (including himself), only by talking to others could you start making sense of yourself and the world around you.

Plato and Alcibiades were among Socrates’s closest friends. While the former went on to document dialogues with his teacher and develop his own system of thought, the latter was a brilliant but headstrong military leader who both admired Socrates deeply and found himself frustrated by his conversations with the old man.

These relationships weren’t just important to Socrates as an individual; they also helped shape the course of Western philosophy.

Socrates had a distinctive attitude toward friendship: he believed true friends should encourage one another to question things rather than simply provide moral support in tough times.

This view remains valid today—real friends ought to push us towards self-improvement by making us think harder about our beliefs and seeking out more profound truths more consistently.

Plato on Friendship: Love, the Soul, and Higher Forms

Plato thought friendship could lead to more than just companionship—it was a way to become wiser, more beautiful, and closer to truth. In two dialogues, Symposium and Lysis, he explored how a deep bond with someone could improve one’s soul and draw them closer to divine, eternal things.

According to Plato, there are various kinds of love and friendship. Some are built on shared pleasures or physical attractiveness, but these bonds are both short-lived and flawed. Real (or “true”) friendship was something else: it had a spiritual or intellectual basis that took both people towards better knowledge and goodness.

In the Symposium, the character Socrates (Plato’s teacher) argues that all love is a ladder that leads from one kind of love to a higher form. It starts with a physical attraction that can bring us beautiful things, but then evolves so that we come to value inner beauty more than outer beauty (for instance).

Plato believed that true friendship was reflective of the soul: like a mirror, good friends didn’t just hang out with you—they saw the best in you and helped you reach your full potential. This meant growing as an individual, both morally and intellectually, towards Goodness.

For him, friends who bonded over deep conversations or shared activities (e.g., wisdom and virtue) were most likely to last a lifetime because their connection went beyond feelings that might change.

In the modern era we live in, it seems Plato may have made a point: real friends shouldn’t just be people who know how to have a great time! They should also inspire one another to think more profoundly, seeking out truths about themselves and the world around them, while becoming their best selves possible.

Aristotle’s Three Types of Friendship: Utility, Pleasure, and Virtue

Aristotle believed that friendship was essential for a happy and fulfilling life—and not just any kind of friendship, either. In Nicomachean Ethics, he split it into three different types, each with its own level of depth.

The first type is a utility friendship. This is when two people are friends because both of them benefit from the relationship. They might work together on business projects or study at the same college, for example. These kinds of friendships often end if one person stops needing the other’s help with things like homework or rides home from parties!

The second type is pleasure friendships: they enjoy doing things together and spend time with one another as long as this remains true. If it stops being pleasant (for example, if one party gets bored or fed up), then there may be no need to continue seeing each other socially, at least not on a regular basis.

According to Aristotle, the rarest and the highest type of friendship is one based on mutual respect, shared values, and a commitment to each other’s moral and intellectual growth. These friendships are profound, enduring, and altruistic because they are grounded in an appreciation for each friend’s character, not the favors each provides.

Aristotle thought that no one could be happy without such friendships. Today, his advice reminds us to cultivate relationships that encourage us to be virtuous, while also challenging and inspiring us. They should help our characters develop (perhaps by setting a good example that we want to follow).

Epicurean Friendship: The Key to Happiness

Epicurus thought that friendship was not just important but essential if you wanted to be happy. While other philosophers believed friends were good to have around because they helped you become wise or virtuous, Epicurus thought having friends was comforting in itself: they made life feel safer and more enjoyable.

If you had good companions, Epicurus believed, then you could share the nice things that came your way and divide up the worries when stuff went wrong. If you were frightened of being alone or dying (and he thought most people were), real mates would help ease those fears.

With this in mind, he set up a school just outside Athens called “The Garden,” where he and his friends lived. They didn’t have much money but were content with simple pleasures such as chatting with each other, eating together, and, of course, enjoying each other’s company.

Luxury goods might make you feel good for a while, but trusting friends are far more reliable sources of pleasure, an idea that remains true today.

However, one has to wonder whether these relationships were genuinely altruistic or simply a means of lessening anxiety and increasing pleasure. Some people claim that Epicurus viewed friendship as something instrumental—a way to achieve peace of mind.

On the other hand, Epicurus’s followers would say he believed friends themselves bring happiness. They are not just useful for making us happy.

Today, many of us feel stressed or lonely (or both) much of the time. This ancient lesson is still relevant: if you want to lead a happy life, fill it with friends! It’s not things that make us happy (or not usually), but having mates around does the trick.

Stoic Friendship: Duty, Reason, and the Cosmic Bond

The Stoics—Seneca, Epictetus, Marcus Aurelius—did not think friendship was about liking someone. They thought it was about being good, doing your duty, and thinking straight. A Stoic did not have friends in order to feel better when he was upset; his friends were all supposed to be wise and rational people whom he knew well.

While non-Stoic philosophers believed you should have a few close friends, Stoics said their idea of friendship could be extended to cover everyone. To them, being somebody’s friend meant treating that person exactly as you treated any other sensible human being, or any other rational creature, whether you happened to know them or not.

Marcus Aurelius, the Roman Emperor who noted down many of the most famous Stoic ideas, wrote that we are all part of one big family. This was because he believed everything in the world followed a law of reason, which humans alone fully understand.

Stoic friendships may come across as somewhat aloof. Nowadays, we’re encouraged to show our feelings and lean on our friends for support. True friendship, for the Stoics, meant being able to stand alone in a good way.

It was about what we bring to a relationship, not what we can get out of it. They also thought that when emotions ran high, reason often went out the window—and they were very keen on reason.

But does this mean they were against having close pals? No. At heart, Stoicism is a practical philosophy that is as useful today as it was when it was developed in ancient Greece and then in ancient Rome.

So yes, of course, they believed that having friends was important—but they also believed there were right and wrong ways to go about it.

The Political and Ethical Role of Friendship in Greek Society

Friendship in Ancient Greece had both a personal and political dimension. According to thinkers like Aristotle and Plato, societies thrive when individuals form strong bonds with one another.

They believed that acts of philia (friendship) underpinned civic virtues such as trust, justice, and cooperation—and that these virtues, in turn, depended on the existence of such relationships.

Aristotle believed that good governance could not exist without friends. Indeed, he held that it was essential for leaders to cultivate bonds based on moral goodness and shared values rather than mere utility or personal advantage.

A political leader who treated his fellow citizens as friends would be bound to rule justly, while one who let selfish ambition guide him might end up as nothing better than a tyrant!

Likewise, Plato proposed in The Republic that a truly fair community relies on strong bonds between its members. They should help each other because they want to, not because they have to.

It’s not hard to see why these thoughts resonate today. Politics are often so focused on what divides people, such as self-interest or just wanting power, that there isn’t much room for ethical leadership or bringing anyone together.

Would nations be better places if those in charge and their voters prioritized friendship, trustworthiness, and the greater good ahead of arguments about policy or who gets what?

The Ancient Greeks had a word for this kind of friendship, which held groups of humans together rather than just individual men: they called it philia. Maybe there is something in their old idea worth considering when we think about how countries can get along with one another (or fail to).

So, What Is the Role of Friendship in Ancient Greek Philosophy?

Ancient Greek thinkers viewed friendship not solely as a bond, although that was important. They also believed it was central to living an ethical and fulfilling life, an idea with echoes in modern politics.

Socrates thought being friends meant doing philosophy together. Plato thought you could use your pals to help elevate their (or your own) souls to higher levels.

Aristotle agreed with his teachers but also saw that there were different sorts of friendships. For Epicurus, having friends was also all about feeling good—he reckoned a happy life was extremely difficult (some might say impossible) to have without buddies.

The Stoic philosophers, on the other hand, believed you should be able to count your friends on one hand. They thought it was important to have lots of acquaintances but only form close relationships with those who shared your values, and that you saw pretty rarely.

Maybe the Greek ideology reminds us that real friendship is more than just being connected. It’s about working together to make the world a better place.