Victorian England was a society that was, at its very core, rigid with repression. Historians attribute this rigid adherence to morals and upright behavior to the period’s namesake, Queen Victoria, and her mild-mannered husband, Prince Albert. She ruled from 1837 to 1901, and Victoria’s reign was characterized by strait-laced civility. It is of little wonder that historians view Victoria’s reign as a contributing factor to another facet of culture at that time, that of Gothic Literature. How did these rigid social mores pave the way to a subversive subculture, in which anything taboo, such as the supernatural, drug and alcohol abuse, madness, monsters, and terror, reigned supreme?

Gothic Literature in Queen Victoria’s Industrial Age

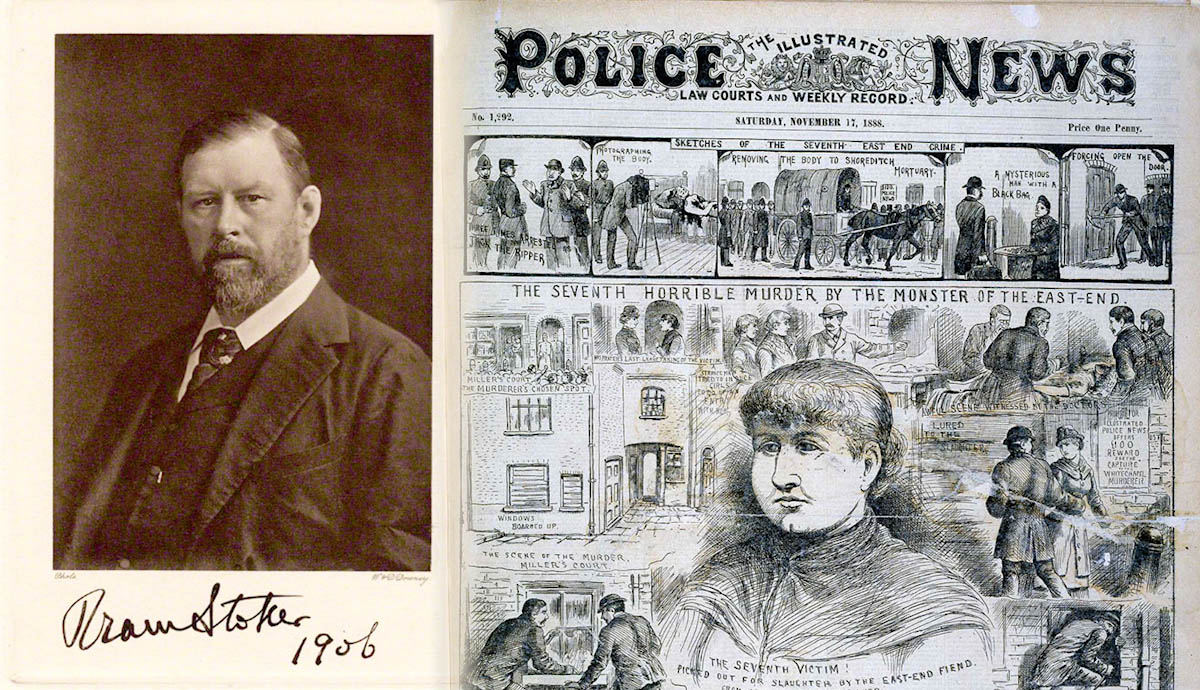

One of the greatest creations of Gothic Literature was that of Dracula, brought to life on the page by author Bram Stoker in 1897. Stoker was, like so many men and women at that time, a member of Victorian England’s burgeoning middle class, a class that had been established during the Industrial Revolution. Newfound wealth from industry meant that this newly established middle class had something their predecessors never had – leisure time. Thanks to the inventive minds of the Industrial Revolution, the middle classes enjoyed artificial lighting in their homes, which meant that their evenings could be spent away in their own private parlors, enjoying leisurely pursuits such as reading. The thirst for anything salacious was an escape from the rigid morality of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert’s dominion over the private sphere. If these readings contained elements of horror, then so much the better.

Bram Stoker himself took his inspiration from many factual elements. While enjoying a week’s holiday on the Yorkshire coast, Stoker was intrigued by the ruins of a medieval abbey called Whitby. This abbey was to become the inspiration for Dracula’s fortress in Stoker’s story.

Part-way through the novel, Stoker’s heroine Mina Murray partakes of some absinthe provided by her supernatural lover. During this scene, her head swirls with visions of a Romanian princess falling from the castle ramparts into the river below. Absinthe was a well-known stimulant used by artists during the Victorian era. Made from the herb wormwood, absinthe would induce in Victorian-era imbibers hallucinations and visions, hence its popularity amongst artists such as Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin.

Supernatural and Murderous Themes: Bram Stoker

In another scene in the story, vampire hunter Professor Abraham Van Helsing talks to his student, Dr. Jack Seward, about the paranormal. The professor talks of spiritualism and mesmerism, urging Jack to open his mind to all supernatural possibilities. Spiritualism was all the rage in the fashionable parlors of the middle classes in Victorian England. Seances were a form of entertainment, and Scottish medium Daniel Dunglas Home was a celebrity in his own right. Home was known not only for his ability to communicate with spirits, but also for his purported ability to levitate. It is therefore unsurprising that this Victorian fascination with the paranormal was injected into Stoker’s Gothic Literature.

When Stoker submitted the first draft of Dracula to his publisher, they rejected it outright. The year was 1897 and Victorian England was still very nervous about anything that was gruesome, bloody, or murderous – all of the things which Dracula was. This was understandable given that only nine years prior, madman “Jack the Ripper” terrorized London’s East End Whitechapel district with a spate of bloody murders. The sexual repression of the era is widely acknowledged as a contributing factor to the psychopathy of this infamous serial killer, whose crimes were sexually motivated. The Irish-born and educated Stoker had been living in London at the time of the murders. One wonders how much of an impact the ensuing media circus around these events had on the author’s fertile imagination when he was conducting research for this Magnum Opus of Gothic Literature.

The Monster Within: Robert Louis Stevenson

As any fan of the Gothic Literature movement can attest, one of its main tropes is a monster that defies the laws of nature. And like Bram Stoker’s immortal blood-drinking vampire, Robert Louis Stevenson’s Mr. Hyde is an abomination of nature. First published in 1886, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by author Robert Louis Stevenson features many gothic themes associated with the genre, which found their origins in Victorian England. Stevenson was born and educated in Scotland. However, he was residing in England by the time his classic novel was published in 1886.

The inspiration for this dualistic character has been debated by academics. Stevenson, like his contemporary and fellow Gothic Literature giant, Mary Shelley, literally dreamed up his monster. His wife Fanny stated that the writer remonstrated with her for waking him from a dream, describing it as “a fine bogey tale.”

Stevenson had an acquaintance by the name of Eugene Chantrelle. Chantrelle was convicted of poisoning his wife with opium, but not before he murdered four more unfortunates with opium-laced toasted cheese. Opium was, along with arsenic, mercury, and morphine, a popular cure-all in Victorian England. Use of this drug as a painkiller was widespread; mothers gave it to their infants for colic, full-blown opium addicts languished in London’s East End opium dens, and the queen herself apparently chewed gum laced with the stuff. In his novel, Stevenson’s dual character takes a chemical concoction meant to induce the effect of splitting his personality in two. After Stevenson saw his former friend go on trial for murder, he was deeply struck by the notion that a man could have two versions dwelling within. One version had an outer appearance of Victorian civility, and one had the brutish savagery that the era so deeply suppressed. Stevenson created a literary legend from this idea, a legend which still endures today when someone is described as having a ‘split personality.’

The Unnatural in Gothic Literature: Embracing the Taboo

Gothic Literature is littered with taboo themes such as lunacy and unnatural human nature. Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte features a madwoman, Rochester’s wife, hidden on the third floor of Thornfield Hall. Rochester’s wife is kept cloistered away from society, for the danger she brings to the household and for the shame she brings upon her husband’s name.

English author Bronte knew all too well how society in Victorian England viewed women who diverged from the societal norm as projected by Queen Victoria, which was to be a faithful wife and productive childbearer first and foremost. Her novel was published in 1847 under the androgynous pseudonym, Currer Bell. This was on the advice from her publisher that her work may not be well-received by mainstream society if they knew a woman had penned it. At the time, women were considered by the medical profession as feeble-minded, prone to child-like outbursts, and vulnerable to hysteria. If a woman’s male guardians – whether husband, father or brother – found her to be quarrelsome or too outspoken, her fate lay in his hands. This sometimes meant being committed to a lunatic asylum.

There was an over-representation of female patients inside Victorian era lunatic asylums. However, some families chose to keep ‘mad’ female family members locked away at home, just as Edward Rochester did.

In 1839, Bronte went on a tour of a medieval manor house called Norton Conyers. It was here that she was told the tale of an unfortunate mentally ill woman who had been confined to the attic. Referred to as ‘The Mad Woman’s Room,’ Bronte was permitted to ascend the stairs to see this attic for herself, which was only accessible via a secret door. The author used this setting as the inspiration for the place of Rochester’s wife’s imprisonment.

It was not only Rochester‘s wife who suffered the taint of madness in Jane Eyre. R. M. Renfield, Dracula’s hapless thrall, is a ward of the lunatic asylum that Dr. Jack Seward oversees. The Victorian belief that madness could be controlled via the use of cold water and cages was evident in Francis Ford Copolla’s 1992 film version of the tale, Bram Stoker’s Dracula. In one disturbing scene, Renfield shows frenzied signs of possession as Dracula psychically communicates with him. The orderlies blast him and the other inmates with ice-cold water, and their heads are entrapped in fitted metal cages. This scene is an accurate depiction of the so-called treatments commonly used in Victorian England to remedy mental illness. These treatments were believed to shock a patient back to a state of sanity.

Victorian England played a vital role in the creation of Gothic Literature. It was a unique point in time, characterized by many elements which found their way into the subversive texts of the genre. If it had not been for conservative Queen Victoria’s pervasive impact on her subjects, and the subsequent utter strangeness of the Victorians – their beliefs and their practices – audiences today would never come to know the terror and the thrill of the genre’s greatest and most enduring creations and characters.