summary

- Foundational Legal Principles: Hammurabi’s Code established the “eye for an eye” philosophy, ensuring punishments were proportional to crimes.

- Modern Judicial Concepts: The code introduced the presumption of innocence and used “if-then” statements to create predictable legal precedents.

- Social and Civil Governance: Laws covered diverse areas like minimum wage and women’s property rights, though penalties varied by social class.

Hammurabi’s Code, preserved on a seven-foot basalt monument, is hailed as one of the world’s oldest written law codes. Codifying 282 laws, the code was developed to reflect life in the First Babylonian Empire in the 18th century BCE, but it contains many modern concepts that feel familiar 3,500 years on. It famously contains the lex talionis, or the idea of “an eye for an eye,” which, while brutal in some respects, introduced the idea that the punishment should be proportional to the crime. It also contains the idea of the presumption of innocence, legal precedents, and legal protections for consumers and women. Read on to discover how Hammurabi’s code revolutionized ancient approaches to law and introduced ideas that still resonate in modern legal codes.

The King and the Pillar of Babylonian Justice

Hammurabi was the sixth king of Babylon’s Amorite Dynasty, ruling in the early 18th Century BCE. His four-decade reign saw Babylon’s influence grow from a small city-state in the shadow of powerful Elam to the epicenter of an empire in control of the majority of Mesopotamia. While Hammurabi is now most famous for his legal code, his rule was characterized by his city’s rapid rise, driven by a combination of diplomacy and military campaigns.

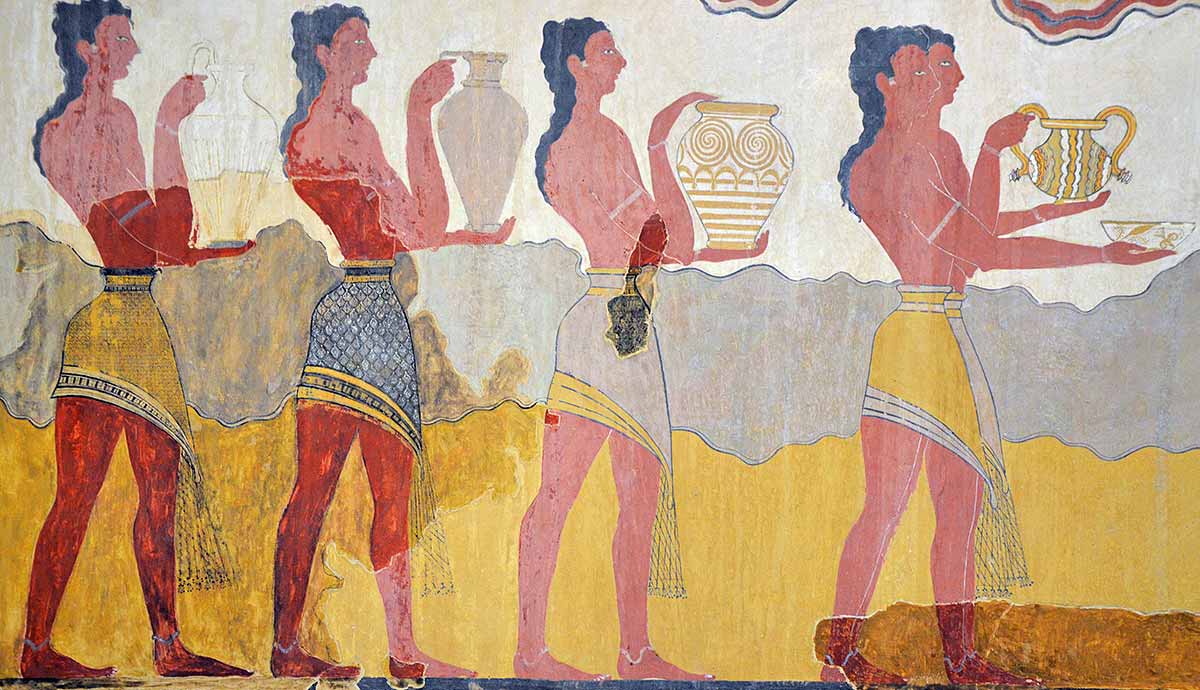

Hammurabi’s law code was discovered inscribed on a 7-foot-tall basalt monument. Carved between 1755 and 1751 BCE, it lists 282 laws and shows King Hammurabi receiving them from the ancient Mesopotamian god Shamash, lending divine weight to the new legal code. Fragments of at least two other similar stone monuments bearing the same text have been discovered, suggesting that the code was displayed in cities around the Babylonian empire.

The Code of Hammurabi was not the first written law code from the region. It is predated by the very fragmentary Code of Urukagina, seemingly composed around 2400 BCE by the king of Lagash to combat corruption. There was also the Code of Ur-Nammu from the Sumerian city of Ur, which was written around 300 years before Hammurabi’s laws (c. 2100-2050 BCE). The Code of Lipit-Ishtar of Isin dates to around 1950 BCE, and the Laws of Eshnunna from Ur, dating to around 1930 BCE. This suggests a move from unpredictable justice based on the whims of a ruler to a codified law that citizens could consult and understand. Something similar would not be seen in Greece until Athens’ Draconian Laws of the 7th century BCE.

Like Hammurabi’s code, these laws were built around “if-then” clauses, stating that “if x happens, then the legal consequence should be y.” But Hammurabi’s code stands apart from previous codes with its focus on “lex talionis,” or “an eye for an eye,” rather than relying exclusively on monetary compensation. This introduced the idea that the punishment should fit the crime. Hammurabi’s code also introduced the presumption of innocence and nuance around social class.

What’s in Hammurabi’s Code?

A full translation of the text on the stele reveals a legal code spanning a broad range of areas of law relevant to life in 18th-century Babylon. The 281 rules take the form of “if-then” conditional statements, usually referring to highly specific situations, for example, “If anyone hires an ox, and a lion kills it in the field, the loss is upon its owner.”

This suggests that the Babylonians relied on precedent for their laws, with legal rulings, presumably made by the king, in the past establishing future practice. They also presumably extrapolated from specific examples to similar cases, for example, what if it were a horse in the field instead of an ox?

One of the most significant components of the Code of Hammurabi is the introduction of the presumption of innocence and due process. The idea that citizens are innocent until proven guilty is one of the central concepts. The code also establishes that cases can be brought before a judge with evidence and witnesses to establish innocence or guilt.

The True Meaning of Lex Talionis

Probably the most famous defining feature of the Code of Hammurabi is the philosophy of “lex talionis,” or “an eye for an eye.” In translating the code, modern scholars quickly identified this philosophy throughout the code. The most famous example is statute 196, which states that if an aristocrat destroys the eye of another member of the aristocracy, his eye shall be destroyed. Similar laws exist throughout the code, with 197 referring to breaking a bone, and 200 knocking out a tooth.

The law can be even more nuanced. For example, statute 230 states that if a builder constructs a house badly and it collapses, killing the owner’s son, the builder’s son shall be put to death.

In the context of the time the law was created, this introduced a limiting factor on the punishment for crimes, establishing the idea of proportionality in crime and punishment. This concept is seen in Roman law in the maxim, “culpae poenae par esto,” which translates roughly to “let the punishment fit the crime.”

This was a major innovation at the time. Previously, justice was largely decentralized, and vengeance and private retribution were largely the responsibility of the injured party or their family. This could lead to blood feuds, with acts of retribution resulting in further vengeance, decimating families. Hammurabi’s code introduced the idea that there was an appropriate limit on vengeance.

Social Hierarchy and Inequality Within the Code

The laws also reflect how oppressive social class structures defined life in Babylon. There were three defined classes: “amelu” (elite), mushkenu (free person), and ardu (slave). Crimes against the amelu had harsher punishments for offenders.

One provision reads, “if a free-born man strikes the body of another free-born man or equal rank, he shall pay one gold mina.” This contrasts with the previous line, which states, “if anyone strikes the body of a man higher in rank than he, he shall receive sixty blows with an ox-whip in public.”

This distinction even applied to the eye-for-an-eye law. If an amelu blinded another amelu, his eye was put out, but if he put out the eye of a mushkenu, he only had to pay a fine. This reflects how deeply embedded social status was in the lives of the Babylonians.

Ancient Laws for Modern Problems

Many sections of the law code feel surprisingly modern in the issues they deal with. For example, toward the end of the text, there are provisions outlining the minimum wage for different jobs. The roles this related to included artisans, laborers, and sailors.

Hammurabi’s law also includes a building code outlining liability if a building collapses. This feels like a modern Lemon Laws, which are consumer protection regulations. Similar provisions are included for injuries sustained during medical operations, although the punishments are less severe for physicians than for builders.

The code also contains several provisions to protect women, especially widows, outlining clear legal rights in relation to property, divorce, and personal safety. This is something else that many modern readers often find surprising, since Babylon was a strictly patriarchal society. It reflects a philosophy that the strong should protect the weak.

If a husband divorced his wife without cause, he was required to return her dowry, and sometimes even a portion of his own property. She also had the right to inherit her husband’s property upon his death, usually an equal portion to the children. Women were legally allowed to own property and engage in business. A woman could also leave her husband due to mistreatment, and sons were also forbidden to mistreat their mothers, potentially to drive them from the household and claim the property. If a wife became seriously ill, her husband was forbidden from divorcing her and was required to maintain her for as long as she lived.

Rediscovery of a Lost Masterpiece

The Louvre stele of the Hammurabi code was discovered during excavations at the ancient Elamite city of Susa in modern-day Iran. The discovery was made between 1901 and 1902 by an archaeological team under the direction of Jacques de Morgan. The stele was found in three pieces and later reconstructed. Although this is the most complete copy available, there are still over eighty lines missing towards the monument’s bottom.

The first report on the stela was published by French Assyriologist Jean-Vincent Scheil, who suggested these lines were erased by Elamite king Šutruk-Nakhunte, who ruled the region in the 12th Century BCE after bringing the statue to Susa. He suggested that the motivation behind the erasure was to add text to celebrate Šutruk-Nakhunte’s achievements.

While theories vary on the exact provenance of the stele, it is generally agreed that it was taken to Elam in the 12th Century. Historian Martha Roth has discussed the difficulties in ascertaining the provenance of the stele, stating that it may have been taken by Shutruk-Nahhunte or his son Kutir-Nahhunte in the 12th Century from one of the locations where stelae were erected. Such locations included Babylon and Sippar, a city under Babylon’s control.

The French Archaeological Mission found the stele in a workroom, indicating plans to add additional text. Roth noted that this would have ignored the original inscription, which threatened that any king who modified the stele would be cursed. The monument’s discovery in this ancient Elamite city reflects an awareness of the code throughout the ancient Near East, even hundreds of years after Hammurabi’s death.

The Lasting Legacy of Hammurabi on Global Law

Copying the Code of Hammurabi played a central role in scribal training throughout Mesopotamia. This indicates the possible influence of the code on lawmaking throughout the region. However, scribes copied other legal texts that were also influential. This suggests that Mesopotamian lawmakers were influenced by a wider legal tradition of which Hammurabi’s Code formed just one part. Still, Hammurabi’s fame in the centuries after his reign may have contributed to his legal code’s influence within Mesopotamia.

There has been significant debate over the text’s influence on later legal systems in the regions surrounding Mesopotamia. Connections have been drawn between the lex talionis principle in Hammurabi’s Code and the Covenant Code, a collection of ancient Israelite laws found in the Bible (Exodus 20.22-23.19), immediately following the Ten Commandments. It contains similar “if-then” scenarios. However, it is unclear whether Hammurabi’s code directly influenced the Israelite laws or if they simply emerged within a similar cultural context.

It is generally argued that Hammurabi’s Code, or at least the law codes of the Middle East, influenced Roman law. Roman law also includes the idea of an eye for an eye and that the punishment will fit the crime, and codifies social hierarchy within the law. Roman law expanded on areas such as property law, debt, and commercial law.

But the main thing that both Hammurabi’s code and Roman Law have in common is that they were written down and displayed publicly, in Rome, starting with the Twelve Tablets in the 5th century BCE. This established stability, predictability, and a level of fairness, which is at the core of most modern legal frameworks. Other aspects, such as legal precedents and the presumption of innocence, are also principal aspects of modern law. Therefore, in many ways, we can draw a direct line from Hammurabi’s code 3,500 years ago to modern legal codes.