Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time transformed philosophy in the 20th century by attempting something huge: trying to understand what it means to exist. Or, as Heidegger puts it, to be Dasein. He asks: how do our experiences in the past and present, our hopes and fears for the future, shape our understanding of what it is to “be” at all? The result is a text that asks us many difficult questions, including whether we have understood anything he has said. Let’s analyze this question in detail.

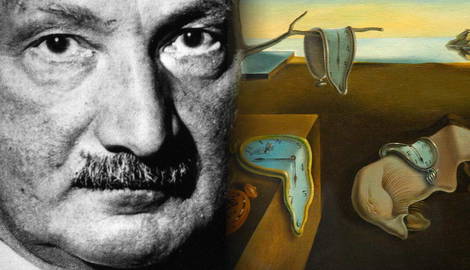

Who Was Martin Heidegger?

Martin Heidegger, a philosopher with difficult but important ideas, was influential in his field during the 20th century. He was born in Germany in 1889 and spent his life trying to understand what it means for something to exist. This made him one of the most important thinkers of his time.

In 1927, Martin Heidegger published Being and Time, which changed philosophy forever. It broke completely with how things had always been done. In this book, Heidegger introduces concepts like Dasein (often translated as “being-there”), saying we should think about humans’ place within the world they live in.

Instead of focusing only outward at objects around them, he suggests people also consider themselves—what does being here mean anyway? What is my experience right now? Am I living authentically or not so much?

However, there is also a negative aspect to Heidegger’s legacy. In the 1930s, he joined the Nazi Party, something that has since caused furious debate about his philosophy and morals. Nevertheless, few can rival the impact he had on philosophy itself.

His thinking helped shape existentialism, hermeneutics, and postmodernism—influences echoed in the ideas of Jean-Paul Sartre, Michel Foucault, and Jacques Derrida, among many others. When a thinker of this stature comes along, people have to pause for thought: What does existence mean anyway?

Heidegger’s Project: Reinterpreting Ontology

In Being and Time, Martin Heidegger takes on the immense task of reinterpreting ontology, the branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of being itself. Specifically, Heidegger grapples with one simple yet profound question: What does it mean to say something exists? And not just this-or-that kind of existence (like mine or yours), but rather the very concept of existence.

According to Heidegger, previous philosophical traditions have failed to address this question. Instead of focusing on the meaning of being itself, thinkers got sidetracked into considering particular beings.

To explain, traditional ontology, as practiced by Aristotle, for example, tends to be fairly taxonomic. It wants to list all the different kinds of things that can be said to exist without necessarily worrying about what “existence” might actually entail.

Heidegger thinks this approach represents a major oversight—and he wants to correct it. His big move involves shifting the discipline’s focus. Rather than continue in this vein any longer—he believes it’s been tried ad nauseam without success—Heidegger proposes a new departure point for philosophy.

Heidegger approached the question using phenomenology, a method developed by his mentor Edmund Husserl. Phenomenology involves directly investigating and describing phenomena as they are experienced, without assumptions or theories.

While Husserl focused on the structure of consciousness itself, Heidegger adapted phenomenology to investigate the structure of existence. He introduced the concept of Dasein (often translated as “being-there”) to describe how humans uniquely exist in the world.

For instance, Heidegger’s idea of “Being-in-the-world” suggests that our understanding of both objects and ourselves stems from how we interact with them in practical activities we carry out every day.

Rather than treating mind and world as separate things—a common assumption in Western philosophy—he shows through this type of phenomenology that they are deeply intermeshed aspects of one another. This perspective may well offer new insights into age-old questions about what it means simply “to be.”

Understanding Dasein

Understanding Dasein is essential for comprehending Heidegger’s philosophy in Being and Time. Dasein, which can be translated as existence or being-there, refers to human beings in a unique sense. They can ask questions about their own presence—unlike any other creature. But Dasein isn’t only passive; it also engages actively with everything around them.

There are several important features of this kind of being: Being-in-the-world, Care (Sorge), and Selfhood. Being-in-the-world suggests that Dasein is always somewhere, somehow involved with the things around it; they don’t experience life from an abstract perspective.

Care links them to both their own potentiality for being and what the world offers for such fulfillment at any given time. Selfhood means making sense of who you are as an individual (realizing possibilities). Nobody else can do this for you. It’s an ongoing activity throughout someone’s life.

The idea of Being-in-the-World is important in Heidegger’s thought. Instead of seeing the mind and the world as separate things, he suggests that Dasein is deeply interconnected with its environment (Umwelt).

This connection isn’t just a cognitive one; it’s practical and embodied, too. For example, when a carpenter sees a hammer, he doesn’t think about hammers in the abstract. Rather, he understands how to use it for building because that’s what hammers do—revealing an interconnected web of relationships.

Heidegger claims that everydayness (Alltäglichkeit) holds key insights into Dasein. Our everyday activities and social encounters disclose something fundamental about our existence. In ordinary life, Dasein experiences the world up close and personal—it has direct contact with what matters most.

So, these daily events should be considered at least as important for understanding as anything else. This shift in emphasis moves away from thinking primarily about abstractions like theory and instead focuses on humans’ lived realities: what we do every day matters; how we engage with others has meaning.

The Concept of Temporality

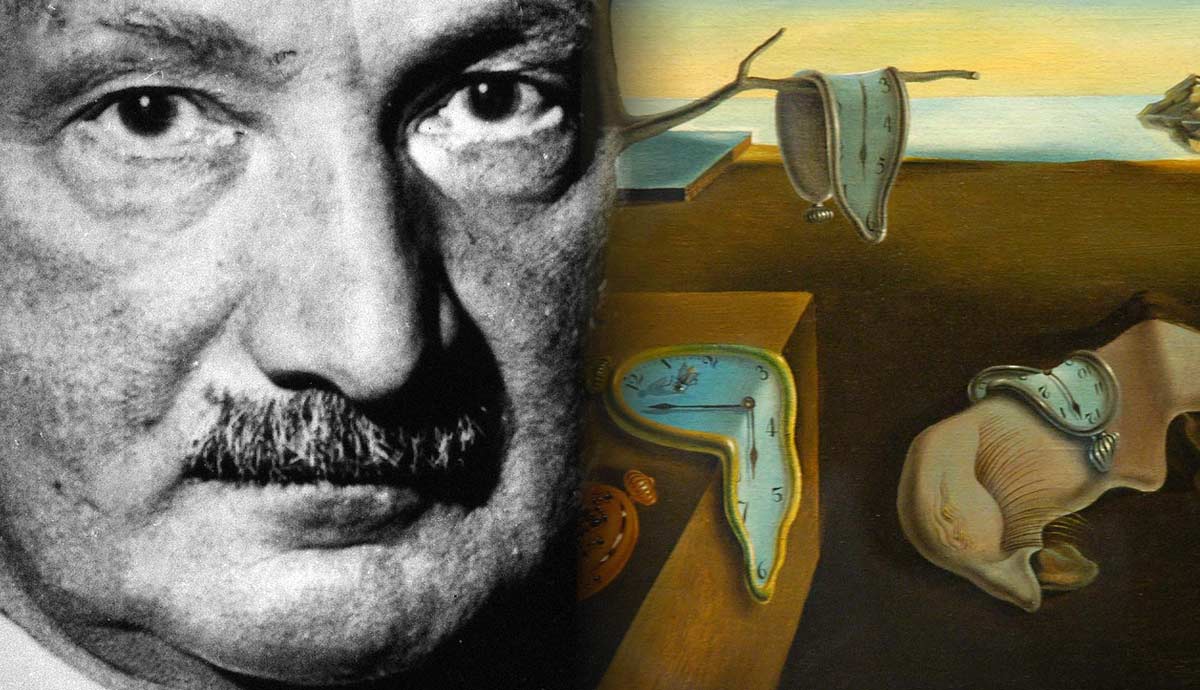

In Being and Time, Heidegger considers temporality to be one of the fundamental aspects behind his philosophy. It acts as a backdrop for understanding Being itself. According to Heidegger, we exist in a temporal sense. Time is not simply a series of moments but rather how we make sense of our own existence.

Heidegger breaks down time into three components: past (having-been), present (making-present), and future (coming-toward). By thinking about this trinity, it becomes clear that we consider what has happened before and how it influences us now, as well as what could happen later on, when considering ourselves and our world.

If we examine our actions at any given moment, they are always influenced by what we have experienced previously and by anticipated possibilities down the line. In other words, time is interconnected!

Genuine and insincere ways of experiencing time separate how people exist within it. When individuals are ensnared by diversions or social norms that cause them to lose touch with themselves—what Martin Heidegger called the “they”—they are in a state of insincerity about time. Their encounter with each moment lacks depth because they merely float along.

Authenticity, on the other hand, reveals itself in how one is “toward death.” Recognizing that our lives will end may prompt us to think honestly about temporality, whether we’re using our limited time well or simply going along for the ride.

This mindset could motivate people to embrace opportunities for personal growth and to live sincerely by consciously being who they really are.

The Interconnection Between Dasein and Temporality

The connection between human existence and time is important for understanding Martin Heidegger’s ideas, and it shows us something fascinating about ourselves. At the core of this connection is a concept called “ecstasis.”

In Heidegger’s view, ecstasis describes how humans stand outside themselves in time. Rather than thinking of past, present, and future as separate things, ecstasis suggests that they all work together to shape who we are.

Within this idea of ecstatic temporality, the past (which Heidegger calls the “having-been”) helps form our current identity and actions, while the future (“coming-toward”) gives us goals or possibilities like a horizon does. And then there’s also what we’re doing right now (the “making-present”).

To give an example: When you make an important decision in life, you think about what has happened to you before (the past) and what might happen next (the future). But then you have to decide firmly, reflecting exactly Heidegger’s notion that Dasein exists in time as a seamless flow.

The concept of Care (Sorge) is essential in grasping how Dasein experiences time. Care denotes the basic state of being of Dasein, involving preoccupation and engagement with the world. This Care organizes the temporal aspects of Dasein’s existence because it always has its sights set on things to be done, objectives to be met, and projects to be completed.

For example, an individual’s career trajectory can be understood through their past education, current job responsibilities, and future goals – all guided by an underlying sense of Care. Through Care, Dasein’s temporality unfolds, revealing a profound relationship between being and time.

So, What Does Heidegger Mean by Dasein and Temporality?

Heidegger’s exploration of human existence and time in Being and Time is deep-rooted in his concepts of Dasein and temporality. Dasein, which translates to “being there,” alludes to how humans exist uniquely by being conscious of their own existence and questioning it. Rather than separating the mind from the world—as traditional thinkers do—Dasein is always “being in the world,” actively enmeshed in its surroundings.

Temporality, meanwhile, is Heidegger’s word for the horizon against which we encounter Being itself: the fact that our existence is fundamentally temporal.

He presents time as a tripartite structure comprising past (having-been), present (making-present), and future (coming-toward). These three dimensions are dynamically interlinked, shaping our understanding of the world as well as how we engage with it.

By connecting Dasein and temporality, Heidegger uncovers a larger scheme in which our past, present, and even future possibilities are all part of the same fluid process. Being aware of this pushes us toward living lives that are authentic expressions of who we are—as beings whose existence has an end—and making choices with significance.