German philosopher Martin Heidegger was born in 1889 in a small town in Southern Germany, where he received a catholic education. He published Being and Time while working at the University of Marburg; he claimed the book contained the first two parts of the rest of his 6-part philosophy. He never completed the rest of it, but the two parts were sufficient to secure him a permanent spot in philosophy as one of the most original and significant thinkers to ever have existed. In 2014, however, Heidegger was dragged into a sphere of scrutiny and disenchantment. The Black Notebooks were proof of Heidegger’s fabled antisemitism, and philosophers and scholars are divided in undertaking Heidegger since.

This article looks into the Black Notebooks to answer the age-old quest of separating the personal from the political and ultimately (in this case) the philosophical. In doing so, it discerns how one may read Heidegger, in light of his antisemitic beliefs after 2014.

Heidegger on Being

What does it mean to be? Why do we not tackle the question of being? Is it possible to actually answer such a question? In trying to answer these questions, Heidegger secured an unprecedented position on the philosophical stage as an original thinker. The object of Heideggerian philosophy is to counter (not supplement) the subject of most western philosophical discourse. The questions that take the form of “Does x (a particular object/subject) exist”, i.e. “Does God exist?” are questions western philosophy has catered to for most of its history since Plato. Heidegger contests these questions and begins by admitting that we do not know what it means for something to exist. Instead, with Being and Time (1927), Heidegger takes on this immensely complicated question – what does it mean to be?

Do we in our time have an answer to the question of what we really mean by the word ‘being’? Not at all. So it is fitting that we should raise anew the question of the meaning of being. But are we nowadays even perplexed at our inability to understand the expression ‘being’? Not at all. So first of all we must reawaken an understanding for the meaning of this question. (Heidegger, 1996)

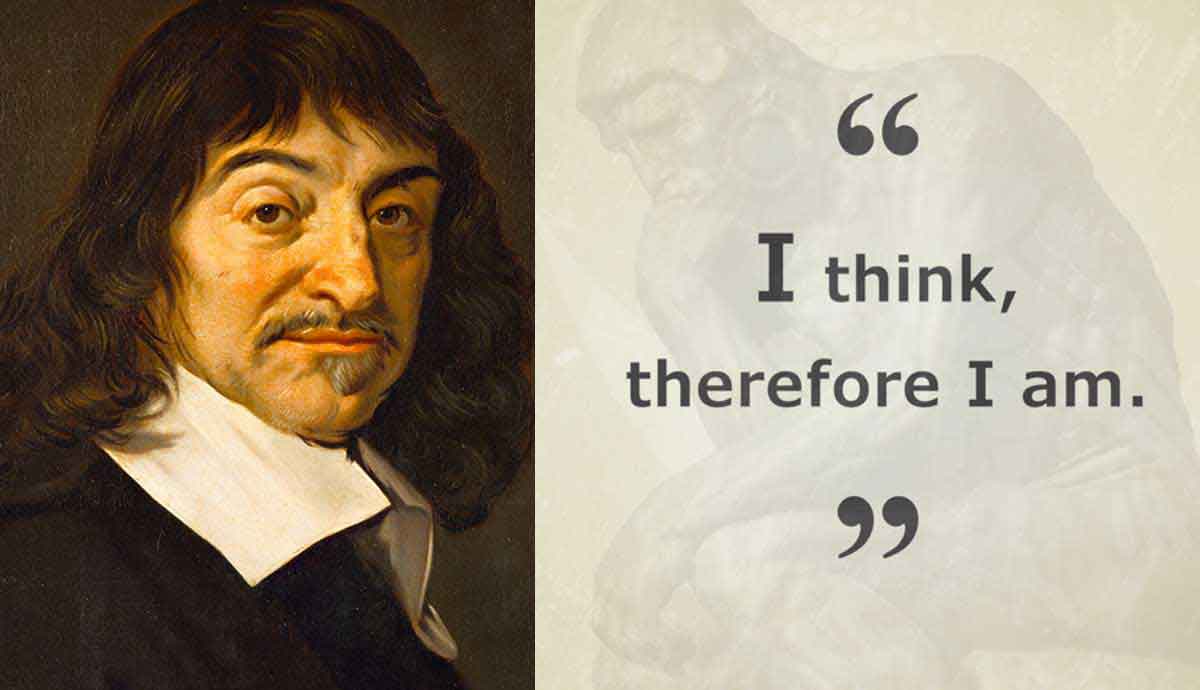

Heidegger is discomforted by Descartes‘ famous maxim “I think, therefore I am” because it presupposes what it means to be. For him, being is the first experience of the human condition. In between being and thought, Heidegger proposed the “Dasein”: literally, Dasein is translated into “being-there”, but Heidegger uses it to denote “being-in-the-world”. With this neologism, Heidegger muddles the distinction between the subject, i.e. the human person, and the object, i.e. the rest of the world- ultimately freeing his philosophy of any prior philosophical undertakings of what it means to exist. It is impossible to exist as a human, disjointed from the world. This also means that it is impossible for human beings to conduct philosophy as subjects that observe an object. For Heidegger, this ontological method, which has been dominant ever since the Enlightenment era, undermines Dasein: what it means to be-in-the-world.

Being is the precondition for all that constitutes living; be it science, art, literature, family, work, or emotions. This is why the work of Heidegger is so important: because it is universal in character insofar that it tackles the question of existing as a person, or even an entity.

Heidegger classifies the being of human beings into conditions of authenticity and inauthenticity. Inauthenticity is the condition of “Verfallen”, wherein a person is subjected to social norms and conditions, where they live a methodical and predetermined life. He says that there is a process by which they can find their ‘authentic’ self again, called “Befindlichkeit”.

When Heidegger talks about Dasein, he attributes the interaction of human beings with the time in which they exist as being central to the condition of being-in-the-world, being in that particular time. The understanding of the present is rooted in the past, and arches towards the future – it is anchored by birth and anxiety about death.

“We reach out towards the future while taking to our past thus yielding our present activities. Note how the future– and hence the aspect of possibility–has priority over the other two moments.”

(Heidegger, 1927)

Heidegger finds that death, the universal character of it, is an underlying structure of the human condition. When a person engages with the world with the anxiety that comes from this structure, they become authentic. This is to say that the condition of Verfallen becomes futile because of the all-encompassing nature of death. After this realization, a person begins to do what they want to do, liberating themselves from the social dictates of everyday life. The only way for a person to approach this condition of authenticity, and to engage with the time they live in, is by challenging the concepts that seem to surround them. As such, for Heidegger, human beings are beings that bring their own being into question.

His philosophy essentially deals with this condition of being, with reference to the existing structures within which the global community persists. Americanism, Bolshevism, Capitalism, world-Judaism, military warfare, liberalism, and national socialism are some concepts he tackles in his phenomenological undertaking of the human condition in his time.

Black Blemishes: Tainting Heidegger

Heidegger’s black oilcloth notebooks, titled Considerations and Remarks, were published In 2014. The author of Being and Time became the subject of international controversy after the four volumes were revealed to be a careful instillation of antisemitism in his philosophy.

To any of the contemporary followers of Heidegger, his Considerations, the first three volumes, and Remarks, the last one of the black notebooks, wouldn’t come as a surprise. Heidegger was a national socialist and wrote about the “Jewification” of Germany in 1916 to his wife. His involvement with the NSDAP and his damning seminars as the rector (Mitchell and Trawny, 2017) are sufficient to understand what his political affiliations were. To other philosophers and students, however, these publications are too large a grain of salt to swallow in the post-Holocaust world.

In Ponderings VII-XI of the Black Notebooks, Heidegger talks about Jews and Judaism. Some of his undertakings which explicitly mention Judaism include:

-

- Western metaphysics has allowed the expansion of ‘empty rationality’ and ‘calculative capacity’, which explains the ‘occasional increase in the power of Judaism’. This power abodes in the ‘spirit’ of the Jews, who can never grasp the hidden domains of their rise to such power. Consequently, they will become all the more inaccessible as a race. At one point he suggests that the Jews have, “with their emphatically calculative giftedness, been ‘living’ in accord with the principle of race, which is why they are also offering the most vehement resistance to its unrestricted application.”

- England can be without the ‘western outlook’ because the modernity it instituted is directed toward the unleashing of the machination of the globe. England is now playing out to the end within Americanism, Bolshevism, and world-Judaism as capitalistic and imperialistic franchises. The question of ‘world-Judaism’ is not a racial but a metaphysical one, concerning the kind of human existence “which in an utterly unrestrained way can undertake as a world-historical ‘task’ the uprooting of all beings from being”. Using their power and capitalistic underpinnings, they extend their homelessness to the rest of the world through machination, to effectuate the objectification of all persons , i.e. uprooting all beings from being.

- (He includes some observations about World War II in its third year of commencement. In point 9, he claims:) ‘World-Judaism, incited by the emigrants allowed out of Germany, cannot be held fast anywhere, and with all its developed power, does not need to participate anywhere in the activities of war, whereas all that remains to us is the sacrifice of the best blood of the best of our own people.’ (Heidegger, Ponderings XII-XV, 2017).

His statements about Judaism show an inclination towards eugenics, something he deliberately frames as a metaphysical inclination. Jews are inherently calculative, and they have taken over the world because of their persistent allegiance to their race, through planning and “machination”. He situates this world-Judaism in his conception of the end of being, thus constituting an important part of what it means to be-in-the-world. By attributing this characteristic to the Jewish community, Heidegger places it at the center of a reach towards the “purification of being”. (Heidegger, Ponderings XII-XV, 2017)

The Personal and the Political

Akin to most forms of political subjection and discrimination, antisemitism manifested itself in various modes of thought and behavior. In the Dialectic of Enlightenment (1944), Theodor W. Adorno identifies some elements of antisemitism, which include:

- Jews are seen as a race, and not as a religious minority. This allows them to be separated from the population, presenting them as an anti-race in comparison to an inherently superior race, obstructing their happiness.

- Jews as responsible actors of capitalism, and oriented towards monetary interests and power. This justifies scapegoating Jews for the frustrations with capitalism.

- Attributing certain natural characteristics to Jews, which are expressions of their tendency toward human domination, making it impossible to defend them as a people, because they inherently possess a domineering tendency.

- Jews are considered to be especially powerful because they are constantly subjected to domination within society, i.e. society feels the need to suppress the Jewish people as a measure of self-defense against their expansive power.

- Otherizing and projecting hatred towards the community in an irrational manner.

The role of philosophy before the Holocaust is no longer contested- philosophers and eugenists worked incessantly and against staggering odds to establish Jews as a race, and, ultimately, to characterize their entire population as a threat. In this context, it appears that Heidegger’s characterization of Jews and his concept of world-Judaism are sufficiently anti-Semitic to blemish his entire body of work.

After the Black Notebooks were published, philosophers and scholars have come forth with their own interpretations and defenses of the extent of Heidegger’s antisemitism and its effects on his philosophy. This has sparked an inquiry into his relationship with Husserl, his professor, to whom he dedicated Being and Time, and his life-long friend and lover Hannah Arendt, both of whom were Jews. In Ponderings VII-XI, Heidegger designates the Judaist calculative capacity to Husserl and goes on to use this designation as a ground for criticism, further weakening the case for Heidegger’s lack of express anti-Semitism.

Arendt has, on behalf of Heidegger, clarified that the involvement of Heidegger with the Nazi party and the subsequent letters to peers and family and several anti-Semitic lectures which would become the Black Notebooks, were all mistakes on his part.

History and Heidegger

We have arrived at a time in history where every published work is subjected to strict scrutiny for bigotry irrespective of the time within which the work was constituted. There are, generally speaking, three approaches one may take in understanding and making use of works that are explicitly bigoted: rejection of the work altogether, selective application of the work (if it is possible to do so), or forgiveness out of compassion for the time wherein the work was conceived. A similar practice is seen in the study of Heidegger since the Black Notebooks were made public.

We can begin with Justin Burke’s defense of Heidegger. Being and Time is considered to be an extremely influential piece of twentieth-century philosophy, and Burke, in his lecture in Seattle in 2015, claims that Being was the work that secured Heidegger his place in the history of philosophy. Since it was published in 1927, Burke expresses discontent with the supplementation of Being and Time by the Black Notebooks. He find, that the Black Notebooks were published about 40 years after Heidegger’s death, and so they have no bearing on Heidegger’s primary philosophical contributions. He goes on to say that Heidegger’s involvement with the Nazi Party was compulsory, as he had to save his place as the rector of the University of Frieiburg. For Burke, the position that Heidegger must be discarded as a credible philosopher because of the Black Notebooks is preposterous, because his philosophy, or the only Heideggerian philosophy that really matters is the Being and Time of 1927.

This exonerating act is constituted by a quantitative approach, stacking Heidegger’s expressly anti-Semitic works against the magnitude of the rest of his works, and a qualitiative approach, which distinguishes the philosopher from the man (Mitchell & Trawny, 2017). The qualitative approach is defeated by one of the first accounts on Heidegger and his antisemitism. Heidegger’s student Karl Löwith published The Political Implications of Heidegger’s Existentialism in 1946. Löwith found that Heidegger’s antisemitism cannot be separated from his philosophy, and this was clearly evident to him much before the Black Notebooks were published. In fact, Löwith made this inference almost 70 years before the Notebooks were published. Victor Farias in Heidegger and Nazism (1989), Tom Rockmore in On Heidegger’s Nazism and Philosophy (1997), Emmanuel Faye in Heidegger: The Introduction of Nazism into Philosophy (2009) further substantiate the affinity of Heidegger’s Nazism with his philosophy. This effectively also refutes the quantitative exoneration, which assumes that only published antisemitism should be accounted for in assessing Heidegger; numerous lectures and sessions supplement the Notebooks and they cannot be avoided.

Peter Trawny finds that while there is no point in pretending that Heidegger’s philosophy is not anti-Semitic, it is not useful to reject his work or even to accept it without scrutiny. He asks, instead, if the individual texts about Judaism are situated within a larger framework of antisemitism, and to which extent this antisemitism manifests itself.

Trawny goes so far as to say that the nature of anti-Semitism is such that is can be “grafted onto a philosophy” but that it “does not make that philosophy itself anti-Semitic, much less what follows from that philosophy”. As such, it is futile to look for the presence or absence of antisemitism in a text, because Heidegger’s works were conceived in a historical context where antisemitism was everywhere.

So, Heidegger should be treated with compassion and acceptance, and his works should be subjected to complete anti-Semitic interpretation to see which parts of his philosophy can withstand scrutiny and which parts cannot. To this end, Trawny presumes that a scholar of philosophy will read his works and discern for themselves whether his works are anti-Semitic or not, suggesting that there is no objective measure of the degree to which his works are anti-Semitic. But what happens when a non-philosopher or scholar attempts to read Heidegger without any context of his philosophical and historical predispositions?

If according to Heidegger himself, the condition of being is constituted by thought, action, and perception, creating a unity in the phenomenology of the being, we must ask, can one thought really be separated from another? When Heidegger tells us that German thought was (then) different and superior to other traditions of thought, that the Jews are a race inherently tuned for world domination through ‘machination’, that the Jews are powerful because they take refuge in their race, and that world-Judaism reproduces itself at the expense of the blood of the best Germans, does he make it possible to see beyond his words anymore?

Does It Matter if Heidegger was an Anti-Semite?

Heidegger is a philosopher who dabbles in existentialism and phenomenology. His style of work is characteristic because he doesn’t attempt to answer questions which do not bear significance to the actual condition of being, so “everydayness” becomes relevant. When he explicitly invokes politics, or geopolitics, even, he purposely puts himself in a position of vulnerability. Out of the hundreds of volumes of his works, Heidegger wanted the Black Notebooks to be published last, as if to say that the Notebooks are his concluding remarks. And it turns out that he did conclude his own philosophy for good, with the heavy and tainted lid of antisemitism.

To read, and to read philosophy, particularly, is to allow oneself to be indoctrinated; to permit someone else to tell us how to think and go about the world. Scholars tirelessly scrutinize written texts for discrimination, because they acknowledge the value that reading has and the way in which it can affect the reader. Literature and philosophy are not only reflections of the times in which they are created, but they are capable of birthing revolutions and wars. So when one picks up Heidegger without any pretext, they put themselves in an extraordinarily susceptible position.

A long time before the Notebooks, Heidegger’s contemporaries were disappointed, skeptical and vocal about his Heidegger’s anti-Semitic undertakings. The Notebooks, then, aren’t capable of exonerating Heidegger on counts of antisemitism in his earlier works. If anything, knowledge of his anti-Semitic dispositions are necessary to read Heidegger. Even if we were to treat the reader as an intelligent person, the genius of Heidegger would likely be beyond them. The only way in which there is any chance that Heidegger can be read and given merit for the rest of his philosophy, would be to inform the reader of his political positions, and leave the task of acceptance and rejection at their discretion. Given the devastating history and effects of bigoted works, however, this compassion would truly be a gamble.

Citations

Heidegger M., Being and Time (1966).

Heidegger M., Ponderings XII-XV, Black Notebooks 1939-1941, trans. Richard Rojcewicz (2017).

Mitchell J. A. & Trawny P., Heidegger’s Black Notebooks: Responses to Anti-Semitism (2017).

Fuchs C., Martin Heidegger’s Anti-Semitism: Philosophy of Technology and the Media in the Light of the Black Notebooks (2017).

Hart B.M., Jews, Race and Capitalism in the German-Jewish Context (2005).