Divorced, beheaded, died, divorced, beheaded, survived – so goes the mnemonic device introduced at some English schools for kids to easily remember some of their country’s most iconic queens. The device sums up our fascination with the King of England, Henry VIII’s wives, nicely. Many of us know how their marriages ended, but few can grasp who these women truly were. So, what was their story? How did they entice one of the world’s most famous monarchs? And how did they contribute to England’s blossoming royal and national identity? Meet Henry VIII’s wives in order, as well as Henry VIII’s children and potential heirs.

Catherine of Aragon: The Most Determined of Henry VIII’s Wives

| Born: 16 December 1485, Archiepiscopal Palace of Alcalá de Henares, Castile

Died of natural causes: 7 January 1536, Kimbolton Castle, England Tenure: 11 June 1509 – 23 May 1533 Nationality: Spanish Issue: Mary I of England |

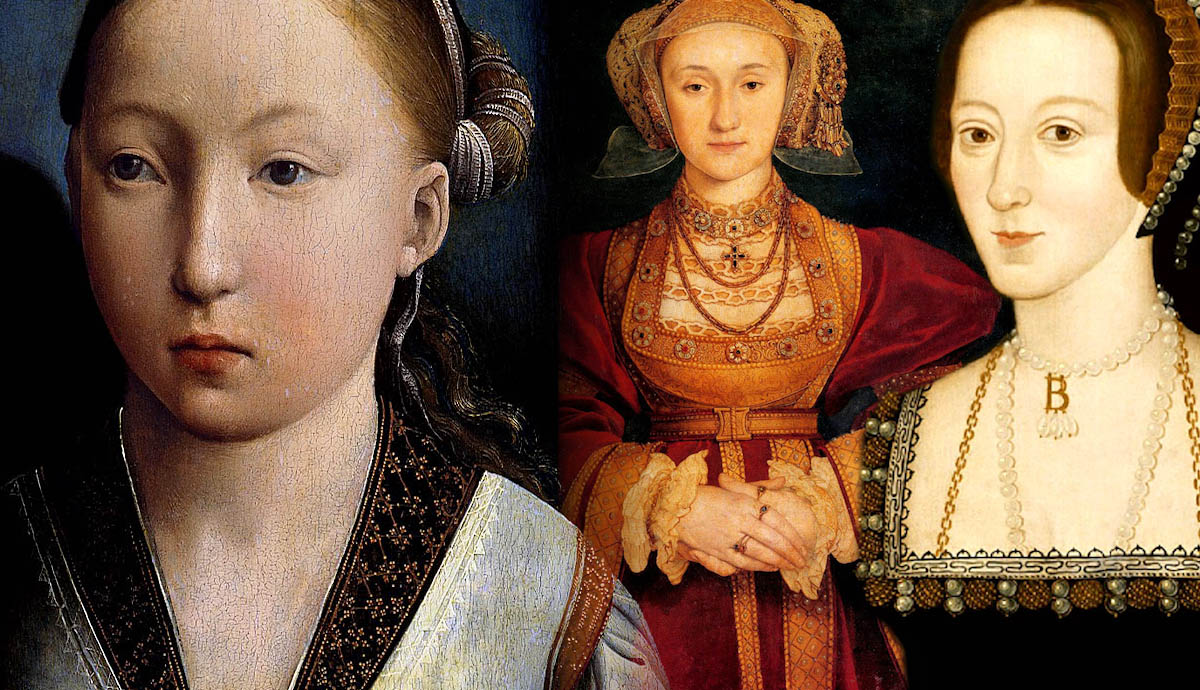

Dubbed by William Shakespeare as the queen of earthly queens, Catherine of Aragon was King Henry VIII’s longest-lasting wife. She was born to the power couple, Queen Isabella of Castile and King Ferdinand of Aragon, whose own marriage had united Spain. But the cultured and highly educated Spanish princess had much to offer beyond her impressive family line. Her diverse and well-rounded education included languages, humanities, and arithmetic, as well as domestic skills. She was a passionate reader and adored good literature, which she had studied since childhood. Catherine was raised to be a queen, but also developed a mind of her own, a trait that will show greatly later in her life.

Catherine had originally married Henry’s older brother, Arthur, in 1501. However, Arthur died barely one year into their marriage, and Catherine was widowed at the tender age of 17. In order to continue to benefit from the strategic Spanish alliance, Henry VIII was to marry Catherine when he came of age and her dowry was paid, which would take a further seven years.

During that time, Catherine lived in London as a virtual prisoner. Her status as a pawn to be used for the whims of the men around her had given Henry VIII’s father, Henry VII, the impression that Catherine would be pliant and easily manipulated. But she had proven herself to be intelligent and strong when she acted as a Spanish ambassador to England in 1507, the first female ambassador in European history

Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon eventually married in 1509, and for the majority of their 24 years together, they were happy. But as the pair got on in years and had failed to produce a living son, Henry started to feel the pressure to secure his legacy. While he had a daughter, Mary, who would later become England’s first queen in her own right, she was not the son and heir he longed for. In time, Henry became convinced that in marrying his brother’s wife, he had committed a grievous sin and, as a result, was denied male issue.

It was then that Henry’s tumultuous reign launched England into a religious and political uproar. Despite the papal dispensation he had received to marry Catherine, he was actively looking for a way out of what he believed to be a sinful marriage. The pope wouldn’t grant Henry the divorce he wanted, and so he was resolved to get it through different means. Between 1525 and 1533, he broke with papal authority, made himself head of the Church of England, and in doing so, consolidated a royal power that answers to God and no one else.

This led the newly appointed Archbishop of Canterbury and a supporter of Henry’s cause, Thomas Cranmer, to declare Henry’s marriage to Catherine null and void. Catherine’s and Henry’s daughter Mary was declared a bastard and was no longer recognized as a princess. In the same year, Henry married Catherine’s former lady in waiting, Anne Boleyn, with whom Henry had fallen passionately in love. Banished from the court and living in exile, Catherine remained strong and steadfast and defended her title as queen until her death in 1536.

During their marriage, Henry had an affair with Elizabeth Blount, Catherine of Aragon’s lady in waiting. They had a son, known as Henry Fitzroy, the only child born out of wedlock whom Henry acknowledged. Born in 1519, the name Fitzroy means “son of the king” in Norman French, which Henry seems to have been happy to bestow when he had no male heirs.

Anne Boleyn: Feisty and Ambitious With a Taste For Reform

| Born: c. July 1501-1507, Blickling Hall, Norfolk or Hever Castle, Kent

Death by decapitation: 19 May 1536, Tower of London, London Tenure: 28 May 1533 – 17 May 1536 Nationality: English Issue: Elizabeth I Of England |

By breaking from Rome, Henry had catapulted England into the protestant reformation. While he himself was initially lured to the cause in order to obtain the power to divorce from his first wife, others saw the reformation as an answer to the abuses of the Catholic Church and the emancipation of the English people. Others, such as Anne Boleyn.

Celebrated Tudor historian Eric Ives has referred to the women Anne Boleyn surrounded herself with as “aristocratic women seeking spiritual fulfillment.” This certainly rings true of the formative years Anne spent at the French Court as maid of honor to Claude of France, where she met powerful female royals such as Marguerite de Navarre. Marguerite openly spoke her mind on religious and political matters and was a well-respected poet and playwright. This could very well have instilled the ideals of the reformation into the young Anne and showed her how women of power can be patrons of the arts and promoters of radical ideas.

By the time Anne had arrived at the English court in 1522, she was a rare and exciting prospect. Contrary to the majority of the ladies, she had a cosmopolitan flair about her. She spoke French fluently, could dance and sing, presented herself in stylish French fashion, played several instruments, and armed herself with a quick, sharp wit. Young noblemen soon flocked to grab her attention, but it wasn’t until 1525 that her skilled game of courtly love caught the eye of Henry VIII.

While Anne refused to give in to the king physically until their future had more solid ground, the two soon developed a deep affection for each other. Their seven-year courtship was passionately documented in a series of love letters. Even during this time, Anne performed important diplomatic duties and was instrumental in solidifying England’s alliance with France.

Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn were married on 28 May 1533. In the same year, Anne gave birth to a daughter, later known as Elizabeth I. However, just like Catherine of Aragon before her, Anne had suffered several miscarriages and had failed to provide Henry with a male heir. Her short three years as queen came to a tragic end in 1536, when she was beheaded on charges of adultery, treason, and incest with her brother George Boleyn, and her daughter Elizabeth was declared a bastard.

Most historians agree that these allegations were fabricated and used to get Anne out of the way. The reason for her removal, however, is still debated. Some agree that Henry wanted to remarry because Anne would not provide him with a son, and that he was the main instigator. Others, however, suggest that Anne’s disagreement on reform policies with powerful men at Henry’s court was to blame for her downfall. While both factors could very well have been at play, what can be agreed upon is that Henry was still waiting for his heir, and he wouldn’t wait long for the next attempt.

Jane Seymour: The One True Love Who Gave Henry VIII a Son

| Born: c. 1508, Wulfhall, Wiltshire, or West Bower Manor, Somerset

Died of postnatal complications: 24 October 1537, Hampton Court Palace, England Tenure: 30 May 1536 – 24 October 1537 Nationality: English Issue: Edward VI Of England |

Looking at Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn, it seems that Henry VIII’s wives were favored for being educated and cultured. But perhaps Anne’s political fervor and Catherine’s resistance were a bit much for Henry, as he next found himself married to their opposite, Jane Seymour. Demure, chaste, and humble, Jane was the very picture of wifely obedience and maidenly behavior. Not as highly educated as Anne Boleyn or Catherine of Aragon, Jane was more proficient in household management and needlework. While not much is known about Jane’s life before the court, she was praised by her contemporaries for being gentle and kind in nature. Imperial Ambassador Eustace Chapuys commended her efforts to bring peace to a fractured royal family when she successfully reconciled Mary, Henry, and Catherine of Aragon’s daughter, with her father.

In October of 1537, a little over a year after her coronation, Jane gave birth to the much-desired and anticipated male heir, Prince Edward VI. But while she had performed her wifely duties in every possible way, Jane soon died of postnatal complications. Henry was deeply saddened by Jane’s death, and there is every indication that if Jane had lived, Henry would have remained married to her. In fact, his true love for Jane is perhaps most beautifully demonstrated by the fact that she was the only one of Henry VIII’s wives to receive an official queen’s funeral and to be buried by his side in St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle.

Anne of Cleves: The Strategic Pawn Who Became a Beloved Sister

| Born: Anna Von Kleve, 28 June or 22 September 1515, Düsseldorf, Duchy of Berg, Kingdom of Germany, Holy Roman Empire

Died of natural causes: 16 July 1557, Chelsea Manor, England Tenure: 6 January 1540 – 9 July 1540 Nationality: German Issue: None |

In 16th-century Europe, strategic marriages were common. Families joined in matrimony, and a political and religious stronghold was built. And yet, Henry’s marriages to Catherine of Aragon and Anne of Cleves are the only ones we can truly call strategic.

After Jane Seymour’s death, it took Henry over two years to move his mind towards marriage again. Lord Chancellor Thomas Cromwell acted as something of a marriage broker as he proposed a marriage to one of the Cleves sisters, Anne or Amelia. A devoted protestant reformer, Cromwell was aware that marriage to either Anne or Amelia would bring with it the support of the Schmalkaldic League, a military alliance of Lutheran princes. This was sure to help Henry VIII secure a more powerful position against the great Catholic forces in Europe.

Court painter Hans Holbein was sent to Germany to paint portraits of both sisters. Together with positive reports, Henry had deemed Anne the most pleasing, and wedding arrangements were set in motion. However, once Henry set eyes on her on their first meeting on January 1st, 1540, his enthusiasm proved to be short-lived. Henry dressed as a servant and rushed to Rochester, where Anne was staying. According to the traditions of chivalry and courtly love, Anne was supposed to see right through the disguise and recognize Henry as her true love. But Anne had no idea how to conduct herself as an English lady. And when she didn’t recognize Henry as the king, Henry’s ego was more than a little bruised.

Despite Henry’s obvious reservations, the two married on 6 January 1540. However, it only took a few months for the new queen to be told to leave the court. And on July 6th of 1540, Anne was informed that Henry was reconsidering the marriage. The six-month marriage was far from a happy one. Not much is known of Anne’s life before she was proposed as Henry VIII’s wife. What we learn about her at court is that she was considered to be kind, gentle, and loved to play cards, but seemed to lack the culture and education to connect with Henry. Anne had been kept in the dark on English customs and was never truly given the chance to come into her own in her new and alien environment.

Finally, on July 9th, their marriage was annulled on the grounds of non-consummation, and the unofficial marriage broker Cromwell, who was a bit too keen to see the marriage succeed, had fallen from grace and was executed. Contrary to Henry’s expectations and past experiences, Anne granted him his annulment with acceptance and grace. She received a generous settlement and, due to her compliance and good nature, was recognized as an honorary member of the family and had earned the status of “beloved sister.” She lived out her life in England in peace and died ten years after Henry died, seemingly of natural causes.

Catherine Howard: A Rejuvenating Marriage of Love and Lust

| Born: c. 1523, Lambeth, London

Death by decapitation: 13 February 1542, Tower of London, London Tenure: 28 July 1540 – 23 November 1541 Nationality: English Issue: None |

The king’s marriage to a woman he felt no attraction for allowed his eye to wander to an altogether more refreshing and, perhaps, extreme prospect, the vivacious teenager Catherine Howard. Catherine Howard’s upbringing was less conventional than that of Henry VIII’s wives before her. She was the first cousin to Anne Boleyn and a second cousin to Jane Seymour, so she did come from an aristocratic background. But while part of the nobility, her father, Lord Edmund Howard, was the third-born son in a family of 21. Following the custom of primogeniture, where the eldest son inherits the estate, Howard inherited nothing. With a family of around ten children to provide for, Catherine’s father was consequently reduced to begging.

When Catherine’s mother died around 1528, she was sent to live in the care of the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk. Due to the Dowager’s responsibilities at court and the several other households she had under her care, Catherine, along with dozens of other poor aristocrats, were often left to their own devices. Flirting and men entertaining the girls in their rooms was common, and Catherine soon received attention from two older men, her music teacher Henry Mannox, and the Dowager’s secretary Francis Dereham.

When Henry openly lamented his marriage to Anne of Cleves, Catherine’s uncle, Thomas Howard, the 3rd Duke of Norfolk, saw an opportunity to introduce sweet young Catherine into the queen’s services. And it wasn’t long before Henry caught sight of the vibrant and giggly teenager. Henry and Catherine married on 28 July 1540, only weeks after Henry’s divorce from Anne of Cleves. The young queen was not old enough to be involved in matters of state, but she was carefree, joyous, and dressed in richly bejeweled French fashion.

However, the marriage would only last a little over a year. Her carefree nature may have been a bit too much, as Catherine was soon accused of being romantically involved with Thomas Culpepper, a favorite of Henry, and the possible existence of a pre-contract with Dereham. As a result, she was stripped of the title of queen in November 1541 and was beheaded three months later.

Poor Catherine Howard had proven to be a pawn of a different kind. While there were no political gains to be made, her joyful and infectious personality was one that had pleased Henry and seemed to have been just what he’d needed at the time. And the offer of a queen’s crown to be lifted out of poverty was no doubt too tempting for her to resist.

Catherine Parr: The Queen Who Brought Stability to Henry VIII’s Court

| Born: c. August 1512, Blackfriars, London, England

Died from complications after giving birth, most likely childbed fever: 5 September 1548, Sudeley Castle, Gloucestershire, England Tenure: 12 July 1543 – 28 January 1547 Nationality: English Issue: Mary Seymour, born in 1548 to Catherine Parr and Thomas Seymour |

Catherine Parr was Henry’s sixth and final wife and the one who’d remained married to him until his death on 28 January 1547. Already widowed twice, the 31-year-old Catherine brought more emotional maturity to the marriage. She took on her role as queen, wife, and stepmother with a great sense of responsibility and furthered Jane Seymour’s cause as a peacemaker at court. While Jane Seymour had first brought up the restoration of Lady Mary, it was Catherine Parr who helped reinstate both Mary and Anne Boleyn’s daughter, Lady Elizabeth, to the succession. In fact, Catherine had quite an influence on the later Queen Elizabeth I.

When Henry went on his last campaign to France in 1544, he left Catherine in charge as regent. She kept close counts on all the finances and provisions for the campaign, signed royal proclamations, and kept a keen eye on the war in Scotland, which ran from 24 November 1542 to March 1551. In Catherine, Elizabeth could clearly observe how a woman could rule in her own right and rule well.

A former catholic turned passionate reformer, Catherine had surrounded herself with a like-minded entourage, including Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury, and Lord Hertford, the late Jane Seymour’s elder brother. This caused some alarm bells to ring with the official “protestant hunters” at court, such as Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester. While attempts were made to have the queen arrested and an official warrant was drawn up, Catherine caught wind of it and managed to convince Henry that the points she had raised on religion did not have any radical ideas behind them. After Henry’s death, however, she published her second book, “Lamentations of a Sinner,” which clearly communicated strong protestant ideals.

Perhaps Henry was persuaded by Catherine’s words. Or perhaps, his declining health and the consequent desire for more stability in his own household convinced him to be less draconian. What we do know is that Catherine was a loving stepmother to Henry’s three children and even took custody of the young Elizabeth after her father died.

The Memorable Queens of Henry VIII

We do these fascinating women a great disservice by remembering them primarily based on how their marriages, or indeed their lives, ended. Their lives and reigns involved more than just being one of Henry VIII’s wives. They were often part of a political and religious game, but they were also women who left their mark on the royal and even national identity by fighting for personal rights, establishing public works, bringing peace to court, and contributing to the intellectual landscape. Their freedom may not always have been great, but their ambitions often were.

The power of these women may be reflected in the fact that after the death of Henry’s son, King Edward VI, born to him by Jane Seymour, he was succeeded by the first ever Queen of England, Henry VIII’s daughter Mary I, and then arguably the greatest ever Queen of England, Henry’s other daughter Elizabeth I.