The “hero’s journey” is a staple of mythology, narratology, and psychology. The Bible contains many examples of this monomyth in its stories of archetypal heroes and their journeys. This includes myths surrounding the birth of the hero, as well as the hero’s inner and outer quests as an adult. The hero doesn’t journey alone but has a mentor and a fellowship. Some of its heroes are unexpected, others are superhuman. But whatever they are, all heroes follow the same story shape — descent and ascent, coming and returning.

Heroic Archetypes in the Bible

Scholars classify the many myths told around the world into bundles that make up the main mythic types. Examples are creation myths, deliverance myths, eschatological myths, dying and reviving god myths, fertility myths, and hero myths. There is, of course, overlap between these main myth types, and not every myth fits neatly into only one category. Some scholars also argue that all myths are ultimately of one type. For instance, Mircea Eliade argued that all myths are a form of creation myth since they all have to do with the origin, beginning, or first manifestation of a thing.

Even within each myth type, there are all kinds of subcategories that classify variations. This reflects the fact that there is not just one sort of hero but many. As Joseph Campbell put it, he or she is “the hero with a thousand faces.” Heroes can be distinguished by the genre of the story in which they appear. Tragic heroes like Oedipus are different from the comic heroes created by Aristophanes and Menander. But heroes also differ according to the heroic archetype to which they conform.

The Bible is a sourcebook for many heroic archetypes. For example, the heroic Messiah archetype derives its name and much of its content from the biblical portrayal of Jesus. This is a hero-as-savior type who endures great suffering and undergoes a sacrificial death to aid others on a national, global, or cosmic scale. Messianic heroes may incorporate other elements into their story too, such as that of the Prophesied One, the Chosen One, the Betrayed One, and the Returning One. The Bible not only fleshes out this and other hero patterns, but it also traces their journey from birth to quest, death, and beyond.

The Birth of the Hero

Before heroes can begin their journey, there are specific conditions under which they must be born. Many scholars have written about the myths that surround the birth of heroes in the ancient world. Perhaps the most famous book written on the topic was by Austrian psychoanalyst Otto Rank called The Myth of the Birth of the Hero (1922). He analyzed classical figures (Paris and Dionysus) as well as biblical ones (Moses and Jesus).

Building on the work of Rank and others, Lord Raglan formulated a point system to measure how much any hero conforms to the heroic archetype found in myths across Indo-European cultures and traditions. Although some of these points have to do with the life and death of the hero, almost half are about the hero’s birth. These are the first nine points.

- Mother is a royal virgin

- Father is a king

- Father often a near relative to mother

- Unusual conception

- Hero is reputed to be the son of god

- Attempt to kill hero as an infant, often by father or maternal grandfather

- Hero spirited away as a child

- Reared by foster parents in a far country

- No details of childhood

Raglan notes that the hero is often driven from their city, and “meets with mysterious death, often at the top of a hill.” Raglan did not include Jesus in his evaluation despite the obvious parallels, due to sensitivities of the time. For him, Oedipus (21 or 22 points) and Theseus (20 points) were the highest-ranked heroes in terms of meeting the criteria of his points system.

Inner and Outer Quests

Joseph Campbell makes it clear that the “hero’s journey” is as much an inner passage as it is an outer one. This is vital in understanding the meaning of the hero’s journey. It is not in the final instance about the distance traveled, monsters vanquished, or riches won. It is about the transformation that the hero experiences along the way. Metamorphosis and shapeshifting are a central theme in the stories of Greek mythology. These outer marvels are meant as pictures of an inner change within the hero as he or she meets them during their quests.

After the patriarch Abraham—known as the Friend of God and the Father of the Faithful—received the “call to adventure” that every hero receives (Genesis 12:1-5) he spent the rest of his life as a pilgrim, wandering from his place of birth to a land promised by God to his yet unborn descendants. His transformation was symbolized by a name change from Abram, as with his grandson Jacob, who was renamed Israel. Similarly, the entire nation of Israel wandered in the desert for 40 years after their exodus from Egypt, until they were transformed from a grumbling, disobedient people into those ready for the conquest of the Promised Land. Outer journeying reflected inner transfiguration.

Heroic Mentors and Fellowships

Although the hero’s journey is one that heroes ultimately take within themselves, that does not mean it is taken alone. Heroes often enjoy company along the way. This may take the form of a fellowship, such as the Fellowship of the Ring, also known as the Nine Walkers in Tolkien’s tale. An example in Greek mythology is the Argonauts of Jason. In the Bible, the most famous instance of this is the Twelve Disciples of Jesus. But there are also the Mighty Men of David (2 Samuel 23) and Gideon’s Chosen Few (Judges 7).

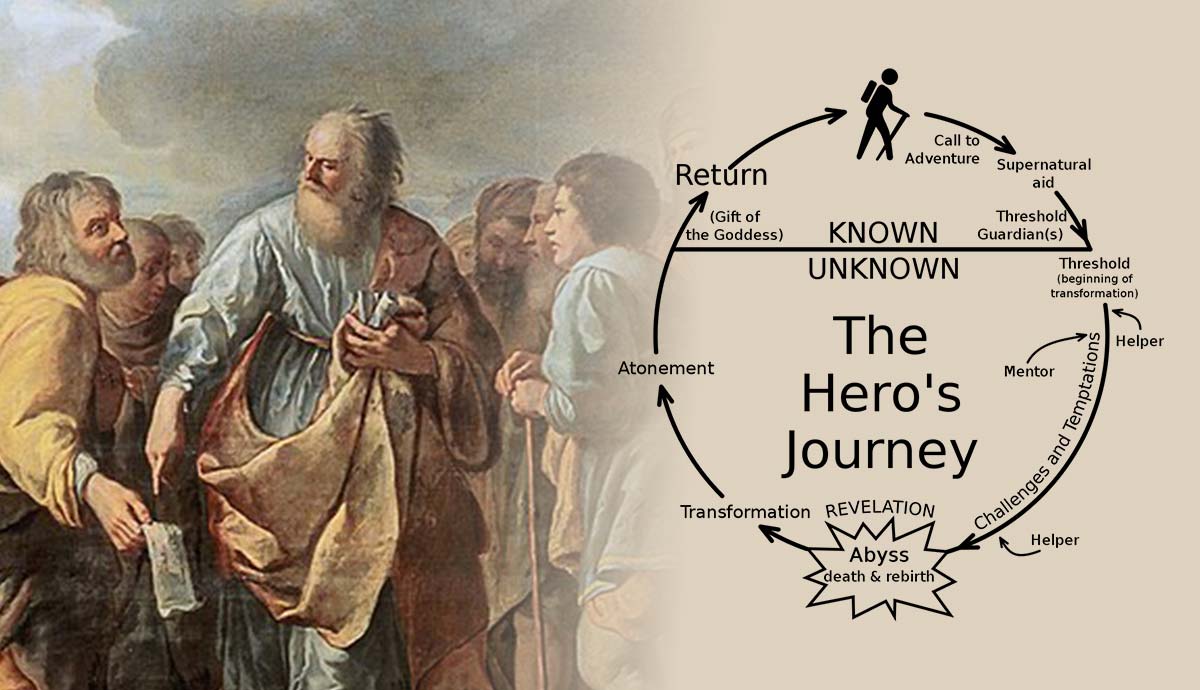

Another relationship for heroes, more important for the start of their journey, is that of a mentor. When mapping their versions of the hero’s journey, Christopher Vogler called this stage of it, the “meeting with the mentor” while Joseph Cambell named it the “supernatural aid.” Both placed it near the start of the journey, in the Departure phrase, before Initiation and Return. A mentor is a figure in a tale who teaches or protects heroes and gives them important gifts. Modern versions include Obi-Wan Kenobi and Albus Dumbledore.

A classic example of a mentor relationship in Greek mythology is Chiron, the wise centaur who acted as a mentor for many heroes, such as Achilles, Jason, and Perseus. A similar mentor/mentee relationship existed in the Bible between many of its heroes. One of the best-known is that between the prophets Elijah and Elisha. Often, those mentored became mentors later on in their journey:

- Jethro to Moses, then Moses to Joshua

- Eli to Samuel, then Samuel to David

- Barnabas to Paul, then Paul to Timothy

This is how heroic values and vision are passed down from one generation to the next.

Expected and Unexpected Heroes

The Book of Hebrews in the New Testament has a chapter that is a list of the biblical heroes from the Old Testament. Chapter eleven is often called the Roll Call of Heroes and the Hall of Faith. Many of the usual suspects are included: Abraham, Samson, Moses, and David to name a few. But there are also some unexpected mentions: Sarah the mother of the nation, Rahab the prostitute of Jericho, and Jephthah the bastard and the outlaw from the Book of Judges (chapters 11-12).

There is a pattern in the Bible of God selecting heroes from outlying demographics. In a patriarchal setting, not only are there heroic Israelite women (Deborah the commander, and Esther the consort) but even heroic foreign women (Ruth and Jael). There is also a consistent tendency for God to select the younger sons over the older (Able, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph). Even the left-handed are included (Judges 3:15). Paul provides an insight into why this is the case in First Corinthians 1:27-29.

“But God chose the foolish things of this world to put the wise to shame. He chose the weak things of this world to put the powerful to shame. What the world thinks is worthless, useless, and nothing at all is what God has used to destroy what the world considers important. God did all this to keep anyone from bragging to him.”

Superhuman Heroes

The heroes of Greek mythology often possess near-supernatural abilities that form part of their stories. For example, the greatest hero of all, Heracles or Hercules, was able to perform incredible feats of strength. Achilles, the greatest warrior of the Greeks at the time of the Trojan War, was invulnerable to damage, except on his heels. Perseus could fly wearing winged sandals. Even Odysseus, although not a demigod like some of the others, had a level of intelligence and cunning that far surpassed his peers. In more explicit ways, these characteristics have passed on to the comic and movie superheroes of today.

The most obvious example of such heroics in the Bible was by Samson, who performed incredible feats of strength, such as lifting up a city gate and killing a lion with his bare hands. The prophet Elijah showed supernatural speed, outrunning a galloping horse after his victory on Mount Carmel (1 Kings 18:46). Daniel and his three friends showed invulnerability to fire and wild animals (Daniel 3 and 6), while Paul proved invulnerable to snake poison (Acts 28:3-6). Philip the Evangelist demonstrated some sort of flight or teleportation (Acts 8:39). On a more mundane level, King Solomon was the smartest person who ever lived. But all these powers were ascribed to the Spirit of God rather than innate attributes.

The Shape of the Journey

The hero’s journey has a definite shape—often called the monomyth—according to mythologists and scholars of literature. In its fullest rendering, the hero’s journey is a circle, with the hero starting and finishing at its top. How many stages the hero passes through, along with their exact nature and names, depends on the author. But most agree that the journey consists of two basic movements: a descent or going down, with a crisis at the lowest point, followed by an ascent or a going up. In technical terms, these are called a katabasis and an anabasis. Not every hero will experience every stage of the journey but they will travel this basic down-then-up route.

Clear examples of this from the Bible are found in the life of Joseph and in the Parable of the Prodigal Son. However, the best exemplar is Jesus himself, in two ways. First, theologians differentiate between Jesus’s humiliation (Incarnation and Crucifixion) and his exaltation (Resurrection from the place of the dead and Ascension). This was his journey from heaven down to earth—in fact, a descent into the depths of hell—and back up. Second, they also distinguish between his first coming and return. Here, the route is one of leaving Earth and then journeying back (the Second Coming, Second Advent, or Parousia). In both cases, this hero completes a circular journey. It is—to use Tolkien’s brilliant expression—“There and Back Again.”