Of all the diplomatic gifts given to the United States, the Temple of Dendur is one of the most famous. It was given to the US in gratitude for its contributions to the campaign to rescue endangered monuments and sites in Lower Nubia, located in present-day southern Egypt and northern Sudan. The acquisition of Dendur was a lengthy and logistical challenge for the Metropolitan Museum of Art where the temple is currently installed. The Met competed with several institutions across the US, and took over 10 years to install the temple before it was opened to the public in 1978.

The Temple of Dendur

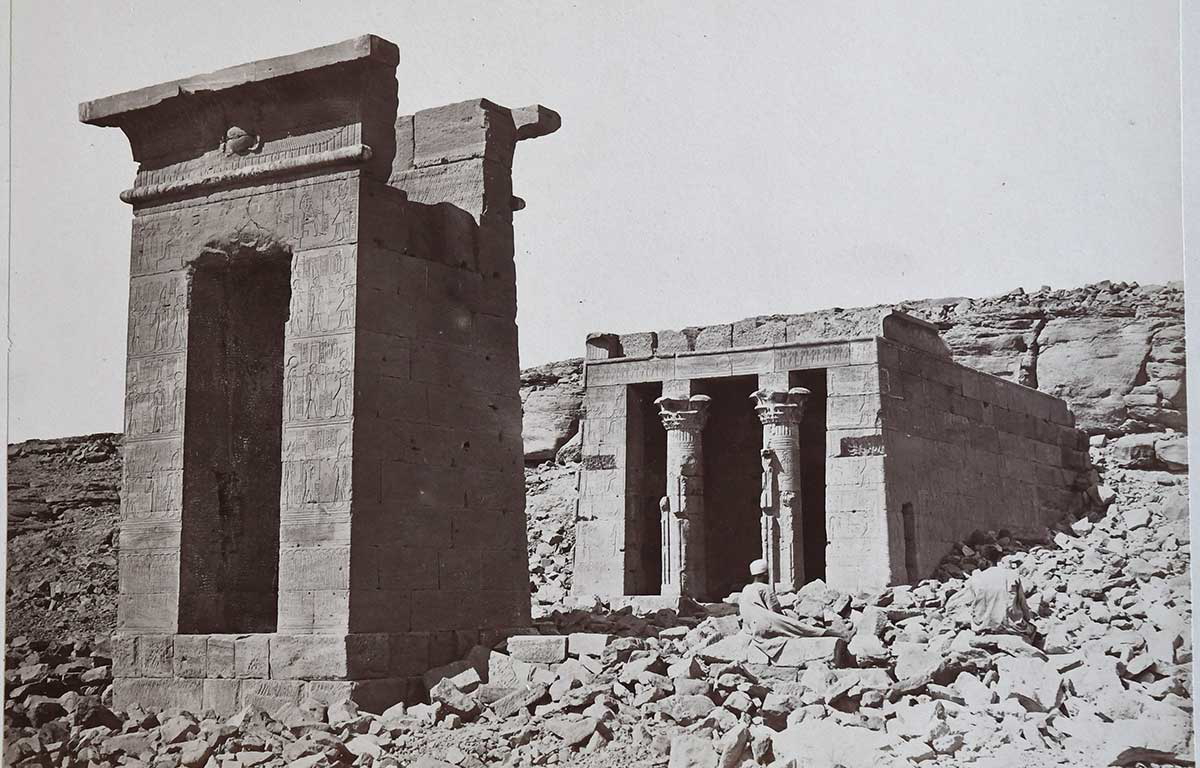

The Temple of Dendur was first completed in 10 BCE, commissioned by Caesar Augustus shortly after he became emperor of Rome. Augustus chose Nubia, which was annexed from the Kingdom of Kush, to encourage a favorable view of Roman rule amongst the local population. He dedicated the temple to the goddess Isis of Philae, an island just north of Dendur, and the sons of a local Nubian ruler, Pedesi and Pihor. After the fall of Rome, it was converted to a Coptic church in 577 CE and was a popular tourist destination.

UNESCO’s International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia

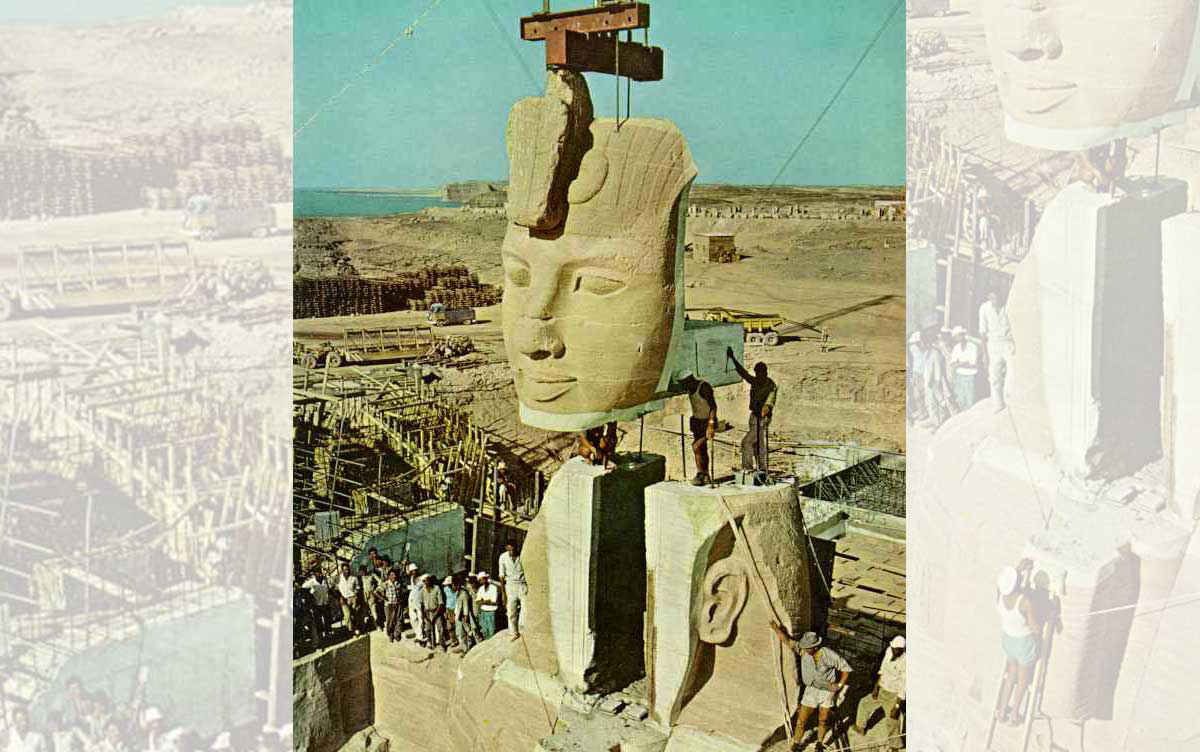

In the 1960s, the Egyptian government began construction of the Aswan High Dam to better contain the annual flooding of the Nile. The project covered two thousand square miles, including the site of Dendur, leading to UNESCO’s International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia. Over fifty countries were part of the campaign, contributing expertise, equipment, and funds estimated at $100 million.

In April 1961, US President John F. Kennedy sent a letter to Congress, recommending that the US participate in the international campaign. Believing that the US had a “deep friendship for the people who live in the valley of the Nile,” JFK wrote that America’s participation would further the country’s interest in ancient Egyptian culture.

The US contributed $16 million towards the effort, which went towards sites including the temple of Philae, known as the “Pearl of Egypt.” In exchange for the preservation aid, the United Arab Republic and Sudan agreed to let American archaeologists excavate areas outside the Nile Valley and take some of the treasures back to American museums.

Dendur Derby

To decide which institution would receive the temple, a commission appointed by the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities reviewed applications from institutions and local governments interested in displaying the Temple of Dendur. Cities including Philadelphia, Miami, Baltimore, Memphis, and Cairo, Illinois threw their hat in the ring, with mayors, senators, and civic boosters all lobbying President Johnson for the temple.

The two main competitors for Dendur were the Smithsonian in Washington DC, led by Dillon Ripley, and the Met in New York, led by Thomas Hoving. There was a preexisting rivalry between the two institutions as they often publicly sparred for acquisitions, loans, exhibitions, and real estate.

Ultimately, the decision for the temple’s placement came down to conservation concerns, and Hoving, who in his presentation to the NEH emphasized the “need for protecting the ‘precious stones’ [and accusing] any plan that did not completely enclose the temple as irresponsible”, won Dendur for the Met.

Installing the Temple

After winning the Dendur Derby, the Met now had the logistical challenges of transporting and rebuilding the temple in New York. In 1963, it had been dismantled and moved to the Island of Elphantine in the Nile and weighed 800 tons in total. The Met sent Dr. Henry G. Fischer, the Curator of Egyptian Art, to Egypt three times to arrange for its handling and packing. Comprised of sandstone, an extremely porous and thus easily damaged material, each stone had to be carefully catalogued and crated to cushion it against the shock of transportation before transport. The stones were packed in a styrofoam-lined crate and gently wheeled into a river craft which transported them to Alexandria before they boarded the Concordia Star, arriving in Brooklyn after a month on the seas.

After arriving at the Met, the stones were first stored in the parking lot in tents where they were examined, cleaned, and conserved. They were then assembled by native Italian stonemasons in the Sackler Wing according to the ancient grooves and incisions left by the initial builders as well as photos and drawings. Consisting of a reflecting pool and floor-to-ceiling glass walls, described as “our master stroke” by the Met’s Vice President for Architecture and Planning Arthur Rosenblatt, the Sackler Wing was designed to evoke the temple’s original location. Of the architectural plan, Chief Curator of Egyptian Art Dorothea Arnold said that the intent was to treat it sculpturally, “so that the temple could be seen as an object, almost as a statue on a pedestal.”

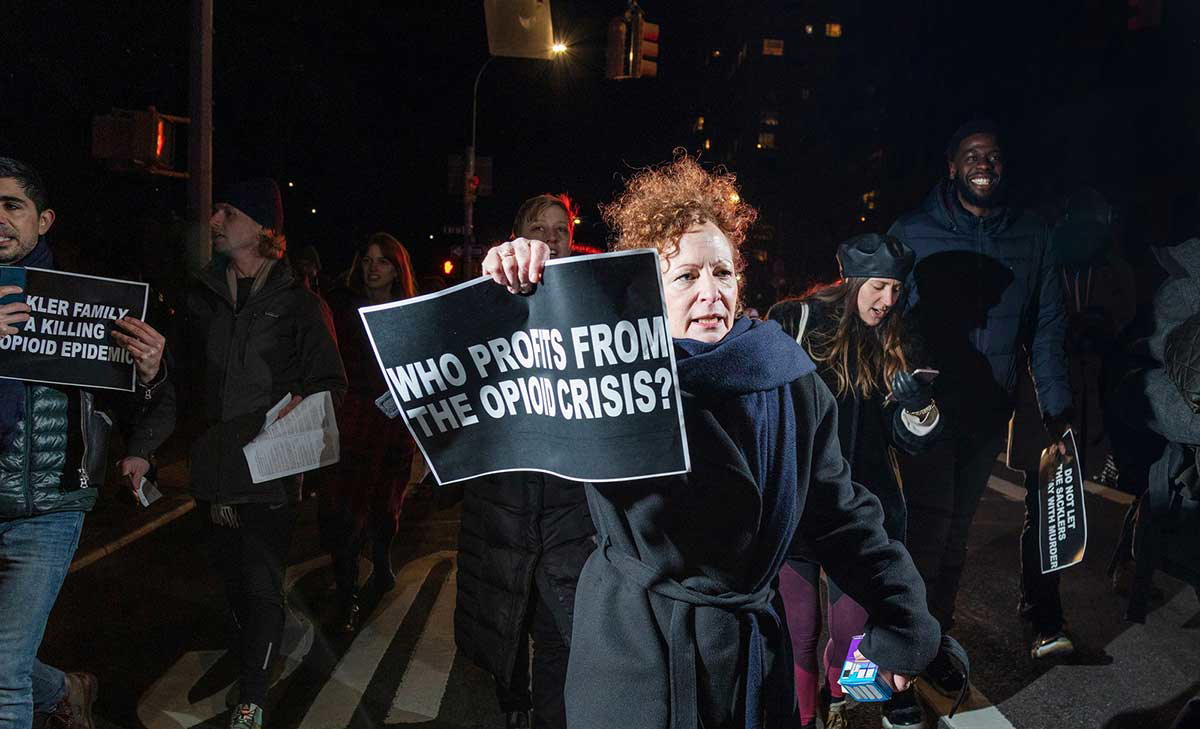

In total, the project cost over $8 million, $3.5 million of which was donated by Arthur Sackler, the namesake of the new gallery specially constructed for the temple. Sackler was a notable art collector and owner of Perdue Pharma, which played a central role in the opioid crisis. As a result of Sackler’s involvement, the site has recently been a site of political protest. In 2019, Prescription Addiction Intervention Now (PAIN), led by artist and activist Nan Goldin, threw pill bottles with labels that read “OxyContin” and “prescribed to you by the Sacklers” into the pool to protest the museum’s connection with the Sacklers. They also held a “die-in” at Dendur, where protestors symbolically laid on the ground.

The Met has since removed the Sackler name from the Egyptian wing and announced that they would no longer accept gifts from the Sacklers. However, the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in the Asian wing and the Marietta Lutze Sackler Gallery in the Modern and contemporary wing still bear the Sackler names. The gallery formerly known as Sackler Wing remains unnamed.

The temple opened to the public in 1978 alongside an exhibition of artifacts from the tomb of Tutankhamun entitled Treasures of Tutankhamun, considered the first blockbuster museum show, and has been an essential part of the permanent collection since its debut. It has since been the site of all kinds of festivities, most notably the Met Gala, and, for a small fortune, available to rent for a party of up to 800.

Bibliography

Booth Conroy, Sarah. “Not by a Dam Site.” Washington Post, September 17, 1978. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1978/09/18/not-by-a-dam-site/203c3b39-731e-4b4c-a54e-d93c4fea47a7/.

Collins, Glenn. “Temple of Dendur Opens Front Porch.” New York Times, January 19, 1994. https://www.nytimes.com/1994/01/19/arts/temple-of-dendur-opens-front-porch.html.

Craig Patch, Diana. “A Monumental Gift to The Met.” Metropolitan Museum of Art. November 5, 2018. https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/temple-of-dendur-gift-to-the-met.

“Egyptian Temple Transported to New York.” Archaeology 22, no. 3 (1969): 228. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41668003.

Harris, Neil. “Presenting King Tut” in Capital Culture: J. Carter Brown, the National Gallery of Art and the Reinvention of the Museum Experience. University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Hoving, Thomas. “Nervous in the Service” in Making the Mummies Dance: inside the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Simon & Schuster, 1993.

“JFK lobbies Congress to help save historic sites in Egypt.” History.com. Last updated May 28, 2025. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/april-7/jfk-lobbies-congress-to-help-save-historic-sites-in-egypt.

Moynihan, Colin. “Opioid Protest at Met Museum Targets Donors Connected to OxyContin,” New York Times, March 10, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/10/us/met-museum-sackler-protest.html.

Pogrebin, Robin. “Met Museum Removes Sackler Name From Wing Over Opioid Ties,” New York Times, December 9, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/09/arts/design/met-museum-sackler-wing.html.

“Social Entertaining.” Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed September 18, 2025. https://www.metmuseum.org/-/media/files/join-and-give/2022-recent/social-entertaining-at-the-met-brochure.pdf?sc_lang=ko&hash=076B5508963B02C449D219A92589001D.

“The Temple of Dendur.” Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed September 18, 2025. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/547802.