The Iliad tells the story of Achilles, a great hero of the Trojan War, and how his uncompromising pursuit of honor ultimately led to the death of his best friend (or lover) and the loss of countless Greek soldiers. The poem explored the cost of individual honor versus collective duty. Through Achilles, Homer presents a hero torn between his desires and responsibilities.

Homer’s Historical Context

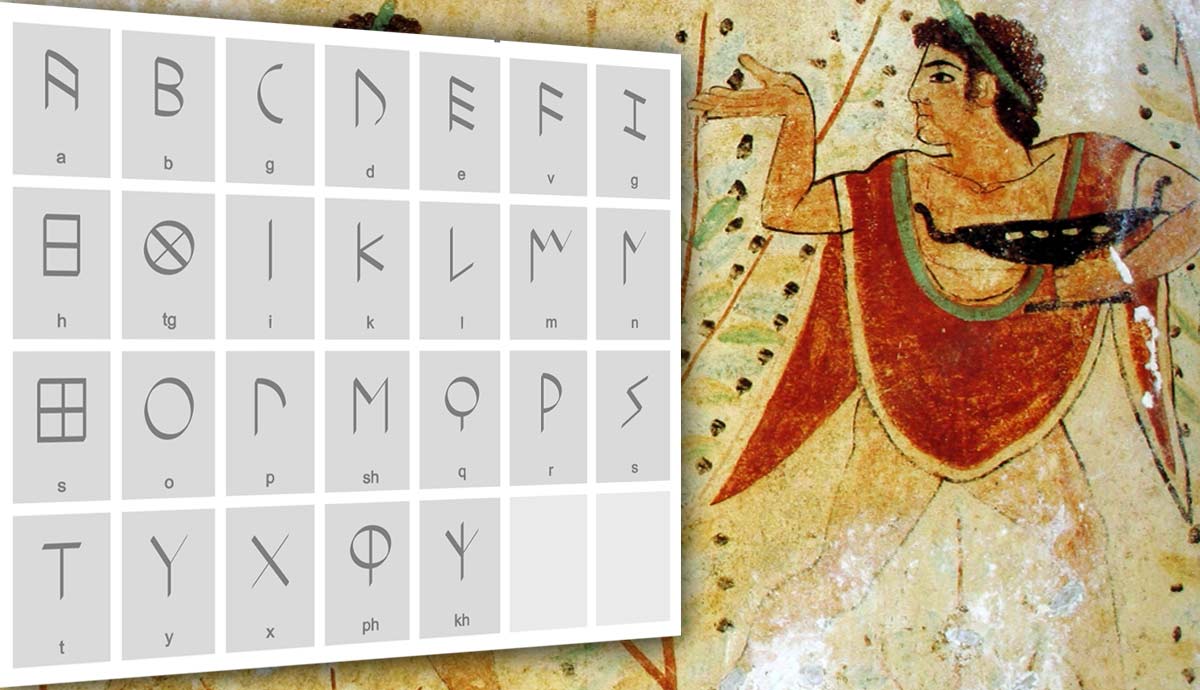

Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey are generally agreed to have been written around the 8th century BCE during the development of the polis, or Greek city-state. During this period, a shift began from the more individualist values of the aristocracy to the cooperative values necessary for the functioning of the city-state. This shift would eventually culminate centuries later with a popular uprising in Athens and the birth of democracy.

Homer’s epics originated from a long tradition of oral history that spanned back to the Bronze Age. While it was once thought that the poems depicted the values of Bronze Age Mycenae, it is now understood that, due to the changeability of oral tradition, it is quite impossible that the stories arrived unchanged down to the 8th century BCE. Certain details, such as the general plot of the epic, probably remained fixed, as they were considered actual history. The Trojans must lose the war, Hector must die, and Agamemnon and Odysseus must survive to return home. What changed was the context and values of the poets who interpreted these events for their audience. This leads to interesting contrasts between the story’s plot points and the source of the epic’s main conflict.

What Happens in the Iliad

The Iliad opens in the ninth year of the Trojan War as a plague ravages the Greek army. Apollo was upset that Agamemnon refused a Trojan priest who had come to him as a suppliant, asking for the release of his daughter, Chryseis. To alleviate the plague, Agamemnon eventually consented to release the girl back to her father, but doing so was an insult to his honor, as she was one of his war prizes. This would leave him diminished in the eyes of others, so he laid claim to one of Achilles’ war prizes, a girl named Briseis.

This action constituted a breach of social conduct as Agamemnon and Achilles were social equals. While Agamemnon was the commander of the armies and had the right to distribute the spoils of war, reclaiming a prize that had been given showed Achilles that he could not be trusted to respect the rights of others. In anger, Achilles withdrew from the war effort.

The tide of the war turned against the Greeks as they no longer had their best warrior, and one by one, their great heroes were injured and had to withdraw from the battle. Agamemnon sent an embassy to entreat Achilles to return to the fight, offering him back Briseis and many other prizes, but Achilles refused. He eventually sent his friend Patroclus, clad in his armor, to fight for the Greeks. Patroclus faced off against Hector, the greatest of the Trojan defenders, and was killed. Patroclus’ death proved to be the turning point in the war as it prompted Achilles to rejoin the fight, his rage shifting from Agamemnon to Hector.

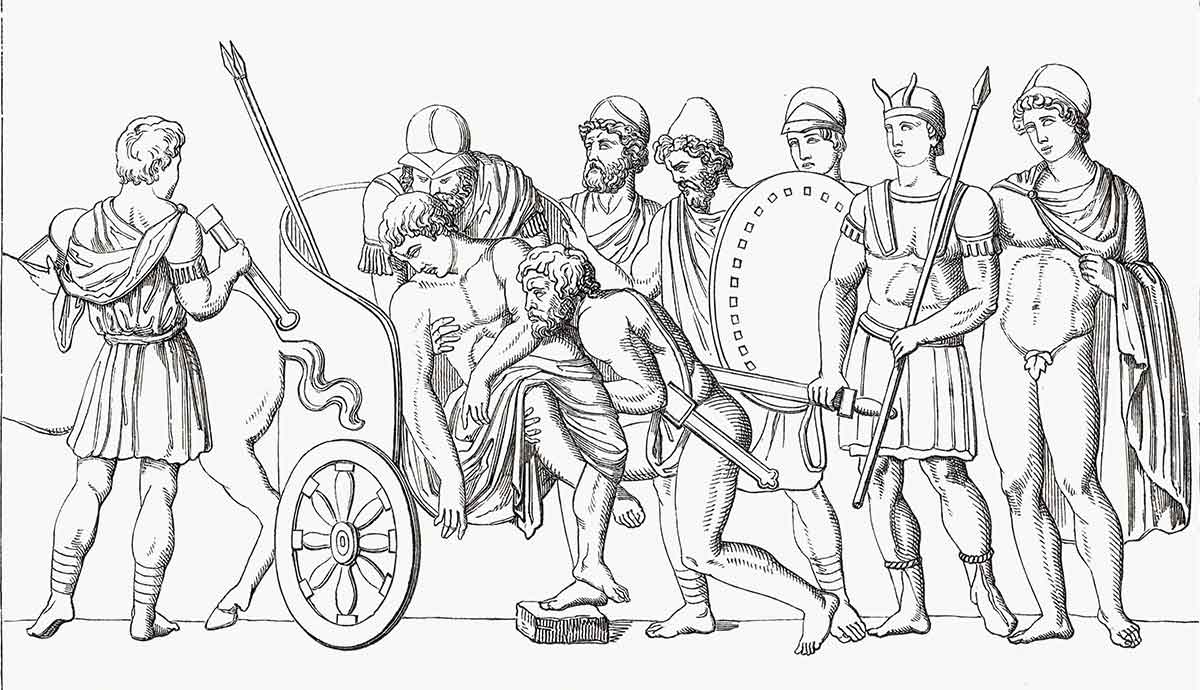

Achilles slew countless Trojans until he finally faced off against Hector before the walls of Troy. He killed Hector and dragged his body behind his chariot back to the Greek war camp. King Priam, Hector’s father, later snuck into the Greek camp to Achilles’ tent and begged for the return of his son’s body. Achilles, feeling pity for the king who had lost so much over the course of the war, allowed him to return to Troy with Hector.

Conflicting Values: Timē vs. Aretē

The main values at stake in the Iliad are timē and aretē. Timē, commonly translated as “honor,” refers to certain privileges allotted to a person based on their social status. This would include the choicest cuts of meat, the finest wines, and plots of land, among other things. Though “honor” is certainly part of the meaning of the word, it also connotes “status” or “prestige.” Timē was not merely an inner quality; it was inseparable from its physical manifestations. In the Iliad, this manifests as the person’s share in the spoils of war. Being given more or less of the spoils signified their rank among their peers, so receiving more or less, in essence, increased or decreased their standing in the social hierarchy.

As timē was something someone was given and not something that could be gained on one’s own, it depended entirely on those who conferred it and not at all on the one who received it. This is true in Homer and remained true in the Classical period. This is evident in Book 23 of the Iliad, where Achilles holds athletic contests before Patroclus’ tomb. The prizes were allotted to men not based on their skill, but on their social status.

Aretē has commonly been translated as “virtue,” yet in Homer, it is generally used in a context that refers to a person’s, or even an animal or object’s, competence or prowess at tasks expected of them. The virtue of a horse lies in its swiftness; the virtue of a woman lies in being a good housewife; and the virtue of a warrior lies in his skill in battle. In Homer, aretē was viewed as being innate to a person and predetermined by birth, much like a horse bred for racing will necessarily be faster than one bred for labor. However, aretē was an active virtue and must be displayed and used for public purposes, else it ceases to exist. A warrior had no value unless he displayed his prowess in combat.

These two values are at odds within Achilles in the Iliad as he tries to rectify the insult and diminishment of his timē with maintaining his aretē as a warrior.

Heroic Expectations

Due to a warrior’s status and timē, there were certain social requirements expected of Achilles. As Sarpedon says in Book 12,

“Glaukos, why in Lycia do we receive especial honor as regards our place at table? Why are the choicest portions served us and our cups kept brimming, and why do men look up to us as though we were gods? Moreover we hold a large estate by the banks of the river Xanthos, fair with orchard lawns and wheat-growing land; it becomes us, therefore, to take our stand at the head of all the Lycians and bear the brunt of the fight[…]”

While a man’s honor was not directly related to his skill in battle, the expectation was that the warrior would at least engage to protect his countrymen. The Greek heroes were bred to be warriors and leaders, which is why they received a greater portion of honors than common folk. They were expected to use their aretē for the common good of the society.

The Value of Pity

Throughout the epic, Achilles grapples with his pursuit of honor, and all the misfortune that befalls him and the Greeks is due to his anger at Agamemnon for diminishing his timē. Though it is clear from the poem that his anger is justified, as the war dragged on and more Greeks died fighting, his wounded pride became less justified. We can see this sentiment in a speech Nestor gave to Patroclus in Book 11. Achilles sent Patroclus to ask who the wounded soldier was that he saw Nestor carrying in his cart. Nestor replied to him, asking why Achilles was now showing pity for the Greeks when, due to his absence, he knows nothing of what’s been going on in the war. All the Greeks’ greatest warriors lay injured and out of the fight. He then says, “Yet Achilles, valiant though he be, careth not for the Danaans [Greeks], neither hath pity.”

In Book 1, Nestor had tried to diffuse the conflict between Achilles and Agamemnon, arguing against Agamemnon taking Briseis from Achilles, showing that he clearly considered Achilles’ anger to be justified. Yet as the epic progresses and Achilles refuses any attempt at reconciliation, Nestor seems to change his mind on the matter. He tells Patroclus, “But Achilles would alone have profit of his valour [aretē]. Nay, verily, methinks he will bitterly lament hereafter, when the folk perisheth” (Book XI, lines 762-764).

Patroclus then returns to Achilles and mirrors the sentiment of Nestor, saying to Achilles, “May it never be my lot to nurse such a passion as you have done, to the baning of your own good name. Who in future story will speak well of you unless you now save the Argives from ruin? You know no pity” (Book XVI, lines 30-32).

By prioritizing his sense of honor above all else, Achilles fails to fulfill the tasks expected of him based on his share of timē. His single-minded pursuit of honor has rid him of the purpose he was supposed to fulfill. So, though he increased his timē by virtue of Agamemnon giving back Briseis and gifting him even more treasures in order to make him rejoin the war effort, his aretē became virtually non-existent. It was only when Patroclus was killed did Achilles realize his error.

“I would die here and now, in that I could not save my comrade. He has fallen far from home, and in his hour of need my hand was not there to help him. What is there for me? Return to my own land I shall not, and I have brought no saving neither to Patroklos nor to my other comrades of whom so many have been slain by mighty Hektor; I stay here by my ships a bootless burden upon the earth” (Book XVIII, lines 98-105).

Achilles realized too late the cost of his inaction. He finally seems to understand Nestor and Patroclus’ words now that the devastation of the war has affected him personally. His sense of pity extends to his lost friend and to the struggling Greek army. He takes responsibility for Patroclus’ death, and the only way for him to atone is by killing Hector and then dying himself. When he finally kills Hector, he is still not satisfied and cannot assuage his grief. He tries to desecrate Hector’s body, itself an insult to Hector’s timē, but Apollo won’t allow it. It is only when Priam, the king of Troy, sneaks into his tent at night to beg for Hector’s return does Achilles’s sense of pity finally extends not just to others with whom he has a personal tie but to his enemy as well.

The Iliad ends not with a final battle, but with an act of mercy. Achilles’ return of Hector’s body to Priam signals a moral shift, from a pursuit of honor to a recognition of shared experience. The epic suggests that true virtue lies not just in victory, but in empathy. Achilles’ journey demonstrates how the warrior code, when followed at the expense of all else, will lead to ruin. Only compassion and mutual respect give one’s personal honor any meaning.