Citizens of the 50 United States enjoy a set of protections and rights guaranteed by the US Constitution, but the same can’t be said for those residing in US territories. Puerto Rico, the most populous US territory, has been in political limbo since it was acquired in the late 19th century. Today it is home to more than 3 million US citizens who cannot vote and are not entitled to the same rights as those residing in the states. What’s to blame for this bizarre circumstance? The Insular Cases.

Background: Puerto Rico Becomes a US Territory

By the late 19th century, Spain’s once-dominant empire in the Americas had been reduced to a few remaining island possessions in the Caribbean. Though it had lost all of its colonies in North and South America after various wars of independence, it remained determined to retain its last few strategic outposts. So, when Cuba declared its independence in 1895, Spain responded with military force.

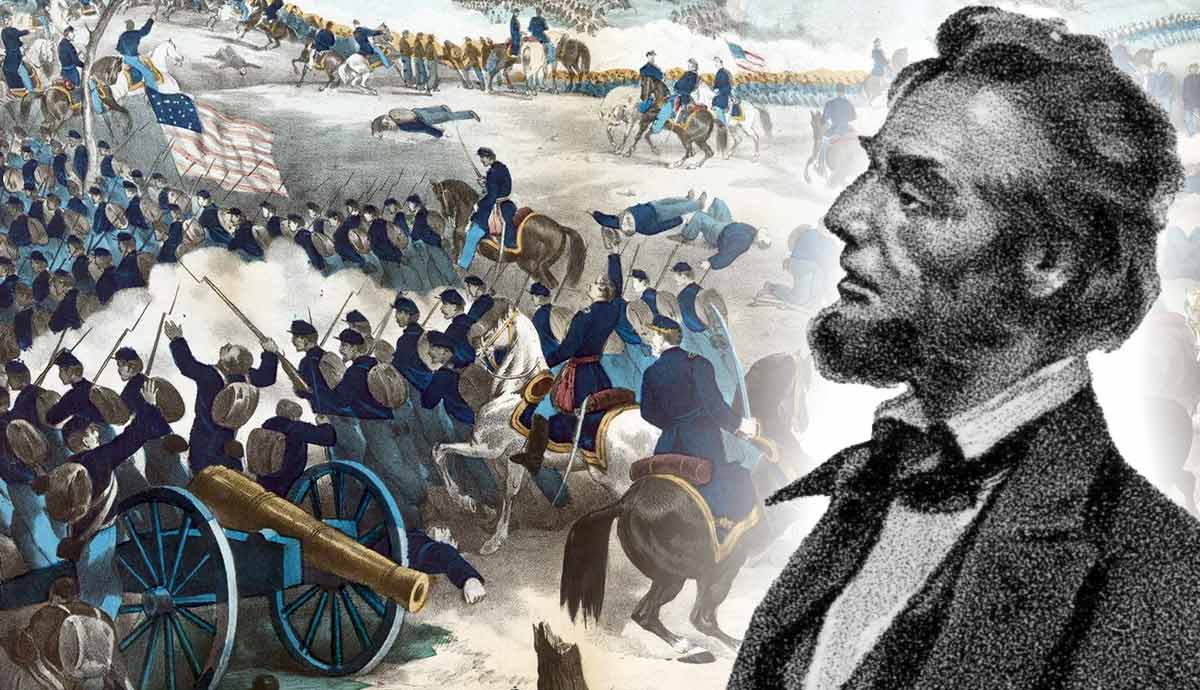

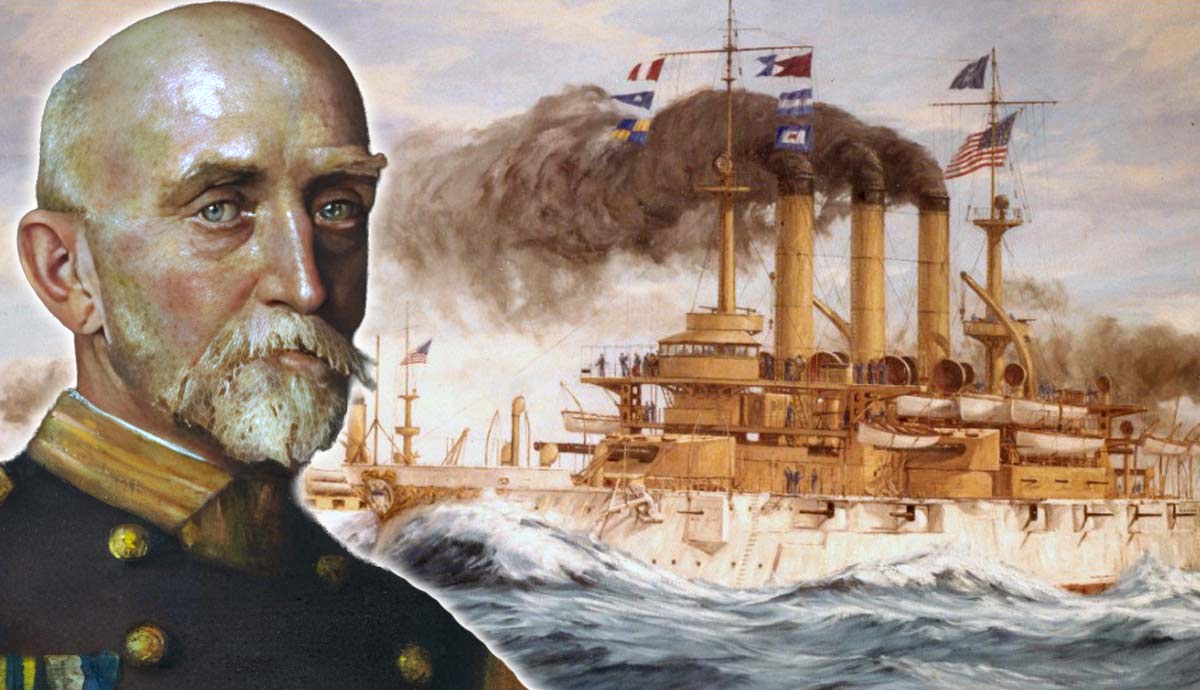

At the same time, the United States had come to see the Caribbean region as essential to its business interests, particularly Cuba. As such, it was sympathetic to Cuba’s fight for independence. When a US naval ship sent to protect US interests in Cuba, the USS Maine, exploded in Havana harbor in early 1898, the US saw it as an act of war—though various investigations since have failed to determine the cause of the explosion.

By April, the US had declared war on Spain. It launched offensive operations in the Philippines, Cuba and Puerto Rico, defeating the Spanish easily, particularly in Puerto Rico, where it faced almost no opposition. With the signing of the Treaty of Paris in December 1898, Puerto Rico became a US territory.

Statehood Off the Table

Once Puerto Rico became a US territory, the issue of how to govern it—and what rights its citizens would have—quickly came to the forefront. For the first year, it was largely treated the same way any other newly acquired territory had been as the US expanded westward. In 1899, a military government was put in place, but by 1900 the Foraker Act established a civilian government in Puerto Rico. While its highest representatives were appointed by the federal government, Puerto Ricans were permitted to elect their own House of Representatives. It was widely believed that the island would ultimately become a state and its residents entitled to the same protections, and subject to the same requirements, as US citizens.

However, after President William McKinley was reelected in 1900, it became clear that his administration intended to pursue a different approach to Puerto Rico and other newly acquired territories. Unlike the newest territories in the continental US, which were largely populated by white settlers of European descent, Puerto Rico’s population was largely mixed race and Black. In the minds of McKinley and his successor, Teddy Roosevelt, these “rescued peoples” and “mere savages” warranted a different approach. A colonial one.

The Supreme Court Steps In: The Insular Cases

In 1901, the US Supreme Court (SCOTUS) began hearing a series of cases that would ultimately determine the political fate of Puerto Rico and other recently acquired territories—though disagreements over which specific cases are included among them persist. Now referred to as the Insular Cases, they arguably began with Downes vs. Bidwell, a pivotal dispute ostensibly about duties: were shipments from Puerto Rico to New York international or intercontinental? The decision, however, didn’t just answer that question. It established a new category of US territories—one arguably based explicitly on race.

The court’s 5-4 decision in this case ruled that Puerto Rico was “a territory appurtenant and belonging to the United States, but not a part of the United States within the revenue clauses of the Constitution.” Justice Henry Brown, writing for the Court, argued that being “inhabited by alien races,” Puerto Rico could not be governed “by Anglo-Saxon principles.” The decision went on to establish an entirely new concept for the expanding US empire: incorporated vs. unincorporated territories. Puerto Rico, being the latter, did not merit the full protections of the Constitution or the full rights of US citizenship. Instead, it was declared, cryptically, “foreign to the United States in a domestic sense” and only undefined “fundamental rights” were guaranteed.

The Downes vs. Bidwell decision laid the groundwork for the subsequent series of cases that, based on the ruling that Puerto Rico was not part of the United States, allowed the federal government to pick and choose which Constitutional protections were “fundamental” and therefore applied to the island and its residents and which did not. Another crucial decision came in Gonzales vs. Williams, a 1904 case that denied Puerto Ricans US citizenship but created an entirely new and largely undefined category for residents of these unincorporated territories: non-citizen national.

Another case the same year, Dorr vs. United States, ruled that residents of unincorporated territories had no right to a jury trial. Even after Congress bestowed citizenship on Puerto Ricans with 1917’s Jones Act, the decision in what’s generally considered the final Insular Case, 1922’s Balzac vs. Porto Rico, asserted that the island’s unincorporated status meant that not all Constitutional protections applied—creating an island of US citizens who did not have equal rights under the law. Further, unlike other citizens’ whose Constitutional rights are (ostensibly) guaranteed, basic rights and protections for Puerto Ricans have been subject to ongoing litigation and re-litigation, creating a sense of impermanence and confusion.

Life After the Insular Cases: Separate and Unequal

The piecemeal and seemingly arbitrary awarding or denial of various Constitutional rights and protections to the island of Puerto Rico and its people resulted in haphazard development throughout the 20th century. For several decades the federal government maintained direct rule over the island, appointing its governor. In 1947, Congress granted the island the right to elect its own governor and in 1952 approved Puerto Rico’s Constitution—but not without making its own revisions first.

The island was redesignated a commonwealth with a degree of political autonomy, yet it remained subject to federal laws and the US retained the authority to strike down any local or territorial laws it determined violated those federal laws. No representation in Congress was apportioned to the territory, so Puerto Ricans largely remained voiceless in the process of developing the federal laws it was subject to, as well as in selecting the President and Congressional representatives that held ultimate authority over the island. Lawsuits continued to be filed throughout the 20th century in an attempt to iron out which rights and protections of the Constitution were “fundamental” and which were not.

Even into the 21st century, rulings in court cases suggest the Fifth Amendment right to equal protection under the law, among others, is still not considered fundamental. It was determined, for example, that it was legal to impose federal payroll taxes for Social Security and Medicare but to provide said benefits at a lower level on the island. Unequal access to veterans’ benefits on the island has also been documented, with testimony provided in a recent statement by the Puerto Rico Advisory Committee to the US Commission on Civil Rights. Most recently, in a 2022 case, United States v. Vaello Madero, the SCOTUS ruled that Puerto Ricans were not eligible for the Supplemental Security Income program.

Some high-profile SCOTUS rulings have also demonstrated the lack of clarity on how far Puerto Rico’s sovereignty extends. For example, there was a period of confusion when, in the Obergefell v. Hodges case, SCOTUS ruled that bans on same-sex marriage were unconstitutional. A Puerto Rican judge argued that the basis of that ruling, the Fourteenth Amendment, did not apply on the island, and therefore neither did the decision. The subsequent series of decisions and appeals regarding the ruling highlights both issues of Puerto Rican autonomy and persistent questions about which parts of the US Constitution apply on the island.

One thing US citizenship has guaranteed Puerto Ricans is the right to live anywhere within the incorporated or unincorporated United States, with the result that several large waves of migration, particularly in the post-WWII period and since 2000, have brought millions of Puerto Ricans to the mainland since the early 20th century. Significantly, the full rights and protections of the Constitution do apply to Puerto Ricans residing in the 50 US states, though, like many other minority groups, Puerto Ricans attempting to exercise their right to vote faced discrimination, somewhat ameliorated by passage of the Voting Rights Act.

Legacy of the Insular Cases

Various legal scholars have argued for over a century that the territorial incorporation doctrine established in Downes vs. Bidwell had no Constitutional basis and that the unequal treatment of US citizens in Puerto Rico and other territories is unconstitutional. Yet, the decisions made in the Insular Cases, despite recognition by the Department of Justice that “the racist language and logic of the Insular Cases deserve no place in our law,” are still used to make rulings in contemporary court cases. In 2022, SCOTUS denied a request to consider whether the Insular Cases should be overturned.

To date, Puerto Ricans living on the island still cannot vote in federal elections, nor do they have equal access to federal support services. They are eligible for the draft and can serve in the Armed Forces but cannot vote for their president. Puerto Rico has no Senators or voting Congressional representation, only a “resident commissioner” who serves as a non-voting delegate. Various non-binding plebiscites carried out over the last several decades have found significant numbers of Puerto Ricans in favor of either independence or statehood, but ultimately only Congress can approve a change in status for the de facto colony.