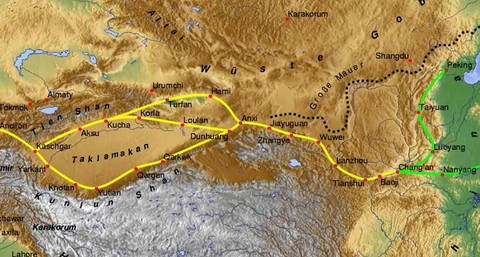

The Han and Tang dynasties changed global history by introducing new tools to the world. The powerful empires provided technologies that would eventually alter civilizations, from the Middle East to Europe. Historians refer to their main contributions as the Four Great Inventions of ancient China which are namely printing, papermaking, gunpowder, and the compass. The innovations reached the Western world through the vast networks of the Silk Road. But beyond the four inventions, other technologies also flowed from China to the rest of the world and made long lasting impacts.

Paper Making

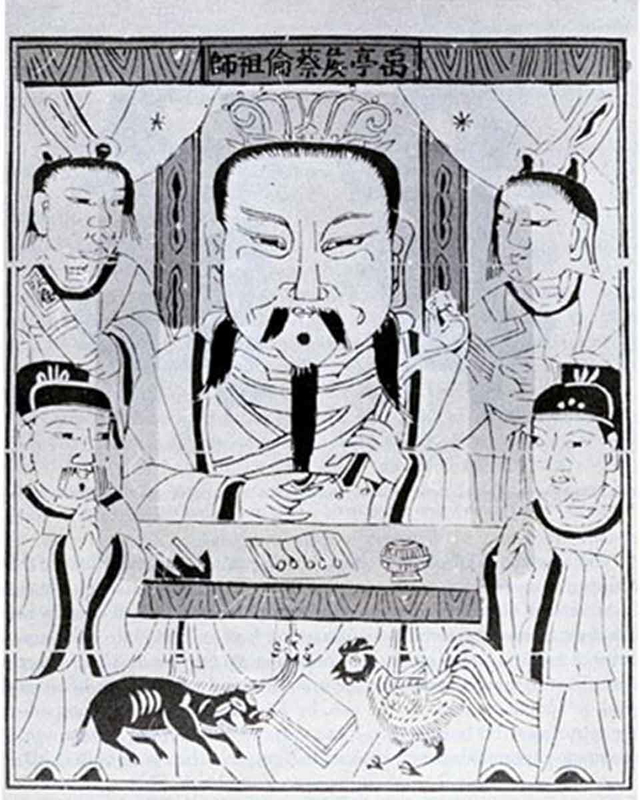

The court official Cai Lun first presented the paper-making process to Emperor He in 105 CE. He manufactured the sheets from a mixture of hemp and tree bark, alongside old rags and discarded fishing nets. The imperial government soon kept the process a secret for many years, while other nations struggled with bamboo and expensive silk. The secrecy, however, ended after the Abbasid Caliphate defeated the Tang army at the Battle of Talas in the year 751.

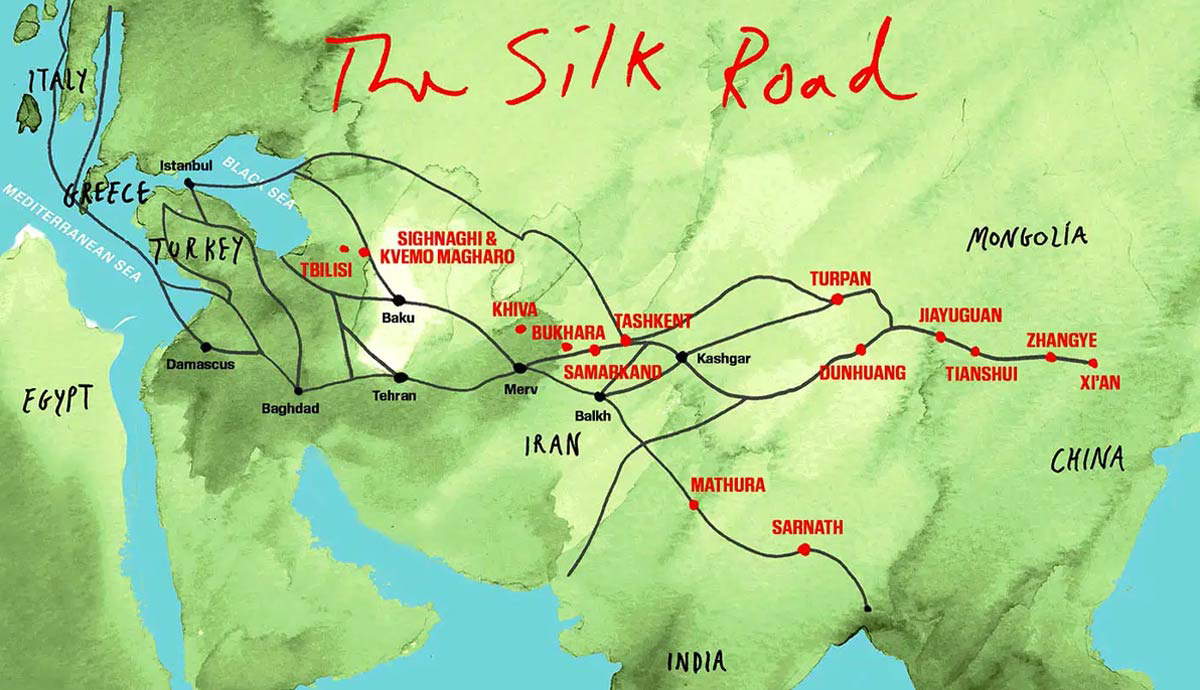

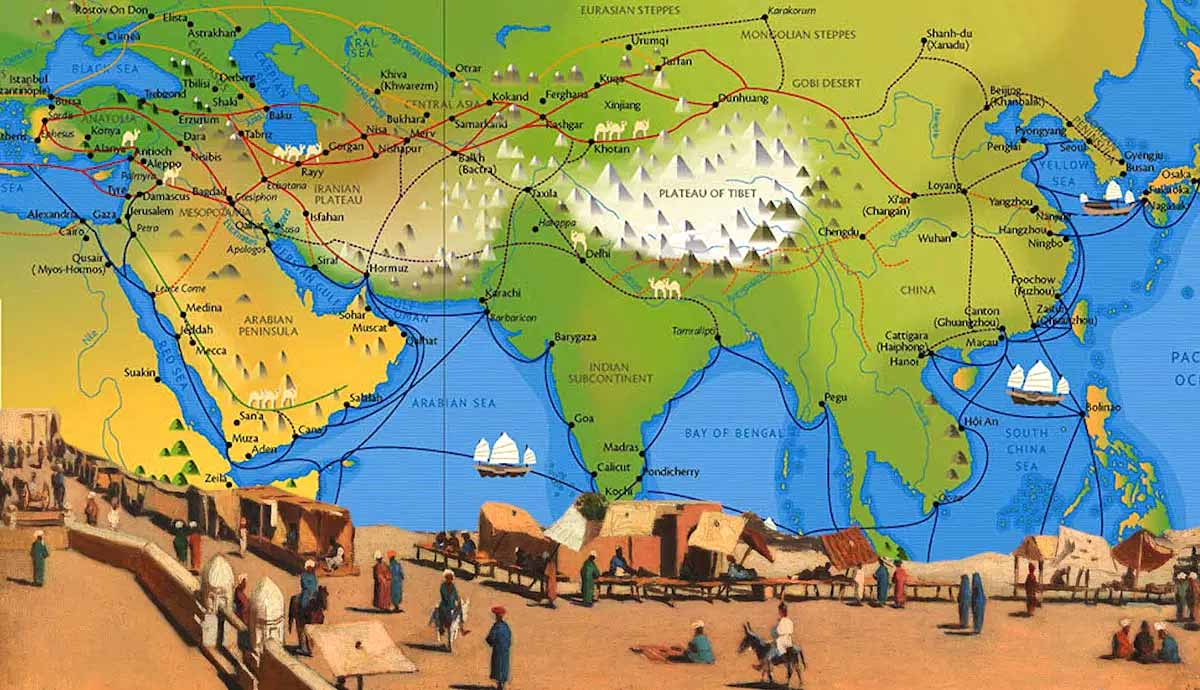

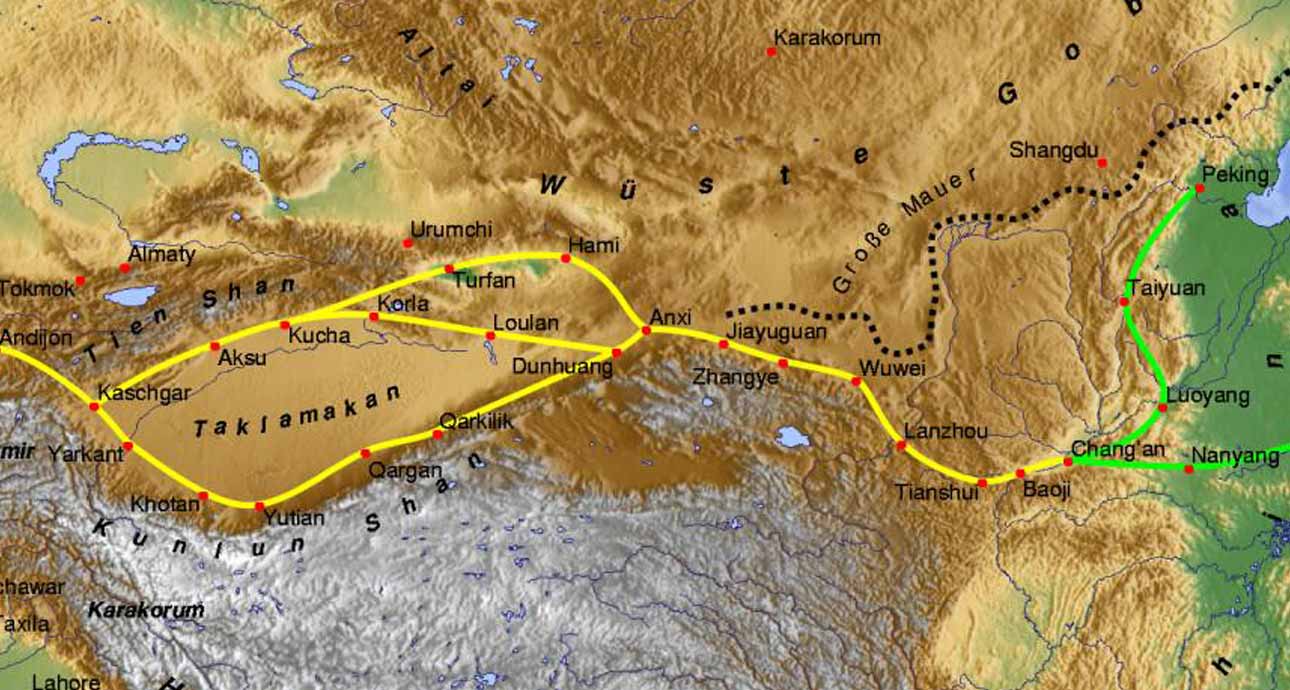

The defeat led to the capture of Chinese artisans. It was these prisoners who revealed the papermaking techniques to their captors, effectively ending the secret. A paper mill was opened in the city of Samarkand by 751 CE. Another followed in Baghdad in 794 CE. Paper soon replaced papyrus throughout the Islamic world by the middle of the 9th century. It eventually reached Italy by the end of the 13th century, where the first documented paper mills were established around the 1270s.

Printing Technology

Printing technology followed a similar journey across the trade routes of the ancient world. The British Library currently holds the oldest dated book which craftsmen created with woodblocks on May 11, 868. The technology that included woodblocks spread from China to regions like the Uyghur Kingdom and Tibet through cultural exchange, along the Silk Road. Merchants from the Islamic world would later discover the technology in Central Asia. The region, however, did not widely adopt the printing of books until several centuries later.

Gunpowder

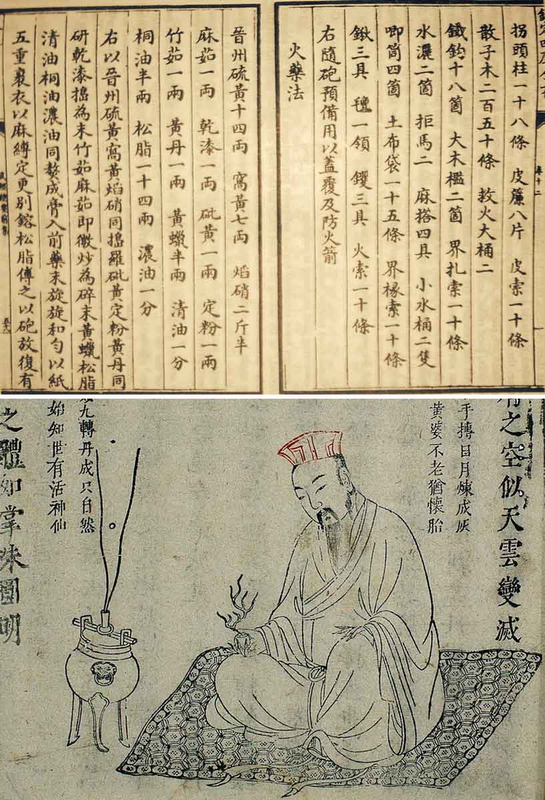

The invention of gunpowder resulted from experiments by Tang alchemists who sought an elixir for immortality. Ancient Daoist texts from the mid-to-late 9th century warned readers not to apply heat to mixtures of saltpeter, sulfur, and charcoal. Military applications were soon developed, with the definitive formula appearing in a manual called the Wujing Zongyao in the year 1044. Notably, a Syrian scholar named Hasan al-Rammah recorded various gunpowder mixtures in his book on war machines in the late 13th century. The evidence indicates that the knowledge had reached the region on the same caravan routes that merchants used for silk by that time.

The Compass

The magnetic compass serves as perhaps one of the most important tools for global history, and traces its origins to the Han era. Chinese diviners used spoons made of lodestone that pointed south on bronze plates as early as the 1st century BCE for geomancy (fortune-telling) purposes rather than for navigation. Merchants and geomancers, at the time, used needles that floated on water during the Song Dynasty in the 11th century.

Later, Arab traders described Chinese ships that utilized magnetic needles for guidance, with records appearing by the mid-13th century. The English scholar Alexander Neckam mentioned the device in 1190, long after Chinese sailors had started using it extensively.

What Other Impactful Inventions Spread from China?

The extensive trade routes of the Tang Dynasty carried a revolutionary product that rivaled the importance of the Four Great Inventions – porcelain. Skilled workers in the Xing and Yue regions used distinct clay formulas and intense heat to produce porcelain bowls and vases. Items were not only waterproof, but also appeared hard and smooth to the human eye. Observers in distant nations marveled at the white objects because the items were much stronger than their own heavy pottery. Aristocrats across Europe desired porcelain for reasons that extended well beyond the utility of the items.

A family secured a position within the highest social circles only if it served their guests in the finest china. Monarchs valued the secret knowledge of production just as much as they appreciated the beauty of the final products. Its appeal was so strong that it once compelled Augustus the Strong, the King of Poland, to imprison a young alchemist named Johann Friedrich Böttger in 1701, forcing him to find its formula. After the formula for hard-paste porcelain was successfully discovered in Europe in 1708, the Meissen porcelain factory was established in 1710. The formula was kept secret by the government for many years.