Since bursting onto the philosophical scene in 1967, Jacques Derrida has attracted controversy. To blame are his anti-essentialist arguments and his rejection of Western logocentrism’s subordination of writing to speech. One of Derrida’s most famous arguments is his concept différance; a misspelling of différence which is absent in speech but visible in writing. According to Derrida, the ‘a’ in the misspelling, différance, proves that without writing, nobody would know the full meaning of the concept. Although his supporters celebrated such concepts as genius, Derrida’s critics severely questioned his academic credibility.

Who Is Derrida?

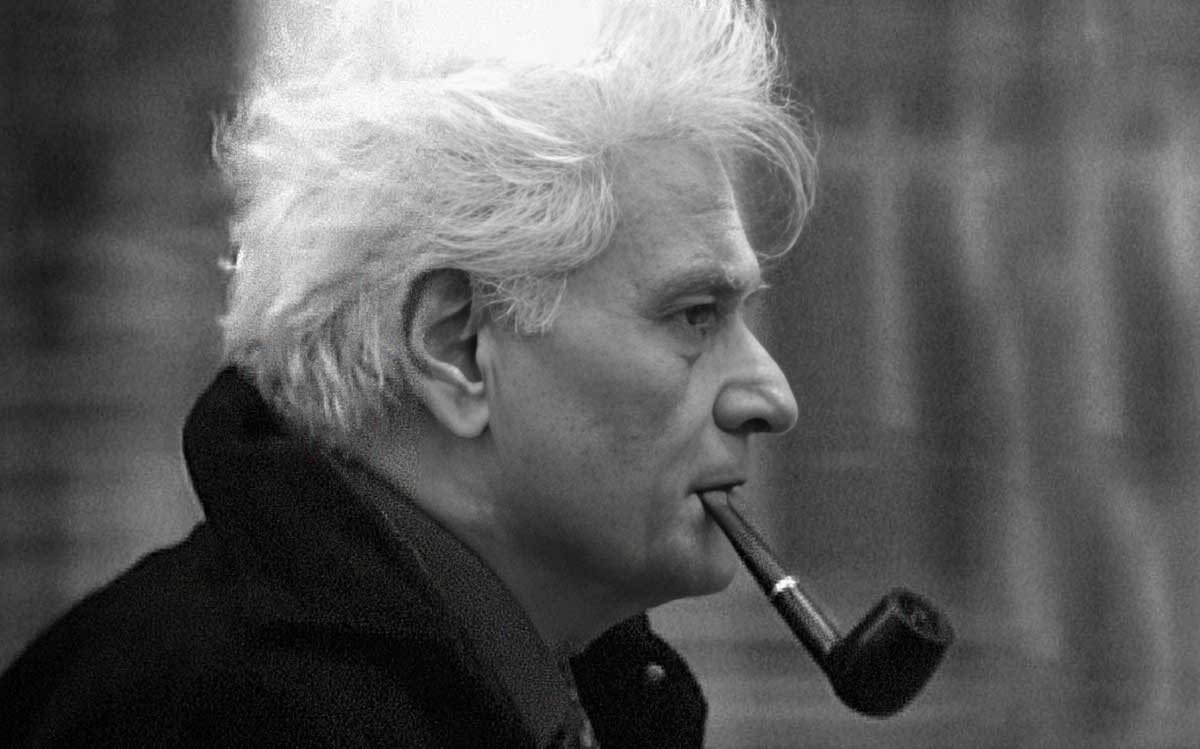

Jacques Derrida (1930-2004) is the infamous Jewish atheist who is, to different readers, a philosopher, theologian, cultural and critical theorist, political thinker, anthropologist, poet and/or iconoclast. Following on from St. Augustine and Albert Camus, Derrida is Algeria’s most prominent cerebral export. An avid reader, over-productive writer, and the father of deconstruction, he was (like Augustine) instructed in rhetoric and consumed by philosophical questions about religion, language, meaning, and truth. But unlike Augustine, Derrida seemed to energetically extol a nihilistic worldview.

Playful and elusive in his writings, and yet fiercely disapproving of those who critiqued him, he saw himself as completely misread even though much of what he was criticised for could be found in his work. And yet, his thought was formed at the highly regarded Ecole Normale Supérieur in Paris, where he completed his Masters’ thesis on Edmund Husserl, founder of phenomenology.

There, Derrida discussed philosophy with his friend, the Marxist thinker Louis Althusser. He spent a year at Harvard reading James Joyce. He taught philosophy at the Sorbonne under such luminaries as Paul Ricoeur, the hermeneutic phenomenologist, and the philosopher Jean Wahl. He introduced his particular brand of philosophy (a mix of phenomenology, psychoanalysis, rhetoric, and linguistics) in various reputable universities—University of California, Yale, Johns Hopkins, European Graduate School—and was influenced by Heidegger, Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, Saussure, Husserl, and Immanuel Kant.

Derrida the Madman?

It was René Descartes who kindled philosophical dialogue around the idea of a mad philosopher. Amid his search for an indubitable ground for all knowledge, Descartes posited that even if deceived by an evil demon to think he existed, the evil demon could only deceive him because he existed. Therefore, he could know he existed by the mere fact that he thought. Or, as he put it, cogito ergo sum, I think therefore I am. In this context, he reduced madness to an illusion that could be overcome with reason.

Michel Foucault saw this as an easy dismissal of the experience of madness. He argued that since the madman is bereft of reason, Descartes’ so-called indubitable ground displays an arrogant overconfidence in its own rationality. But for Derrida, Foucault’s former student, because Descartes considered the possibility that the evil demon could be manipulating him into insanity, his cogito argument was nonetheless valid. Mad or not, cogito ergo sum.

This disagreement precipitated a longstanding rift with Foucault. Here, it serves as an interesting background for our consideration of madness in Derrida’s career-defining arguments. Take for instance his well-known statement Il n’y a pas de hors-texte which has been variously translated as “there is nothing outside the text,” “even unnumbered pages count,” “there is nothing free of context,” or “nothing exists outside language.” This statement captured Derrida’s position that meaning and knowledge cannot be grounded in or established on God, author, principle, or any other foundation outside of cultural history.

With its associated concept, différance, Derrida argues that meaning is stymied by difference and deferral in relation to consciousness’s processing of language through time and space, e.g., letter to word, sentence to paragraph, chapter to book. For Derrida, consciousness, normally aligned with presence—“I am conscious of this”—is influenced by the unconscious, typically considered in terms of absence—“I think he’s unconscious.” So what may be “present” in our meaning-making (as we read) may be tainted by our unconscious; i.e. the latter influences our interpretations. Moreover, the meaning of a word is symbiotic in its difference from the meaning of another word it is related to in a language system—the one contaminates, negates and dilutes the other.

Derrida’s point is that as you read, your mind is haunted by absence. But so are the words you read. Because both your mind (conceived by Nietzsche as something of a prison-house, and by Derrida as a prison of culture and history) and the words being “presented” to it have been formed in, or determined by, time and space; as have the writer’s.

Therefore what I have written and what you are reading are not quite the same thing: you and I are on parallel escalators going in different directions. My words are mere traces (Derrida’s concept) of your understanding, and your understanding are traces of my words: we each have only what’s in this text and I cannot ground meaning for you and neither can you for yourself or my text, because of the differences within our language system and the deferral or absence in our consciousnesses as we read and write. Put simply, a static meaning to a text does not, and cannot, exist.

Critics pointed out that this argument was nothing new and taken to the extremes that Derrida seemed to with Il n’y a pas de hors-texte, “irrational.” After all there appeared to be some agreement, albeit stated differently in various publications, that he seemed to say that différance was about what is differed and deferred in meaning. But, if no static meaning to any text exists then neither can there be any meaning to différance or to his argument that “there is nothing outside of a text or of language.” Indeed, there can be no meaning to any of his writings: all of which manifested from his readings of Western philosophy’s canonical texts and amidst pseudo-Barthesian “death of the author” (viz. no author can be appealed to as a ground to meaning) anti-intentionality polemics.

In view of this and other self-contradictions—for instance Derrida equating “author” with God while actively seeking Him out in religious questions—the temptation to see madness in him was too great. And, in protest to the University of Cambridge awarding him an honorary doctorate, philosophers worldwide published an open letter labelling him “antirational” which is, ironically, Descartes’ literal definition of madness.

Derrida the Genius?

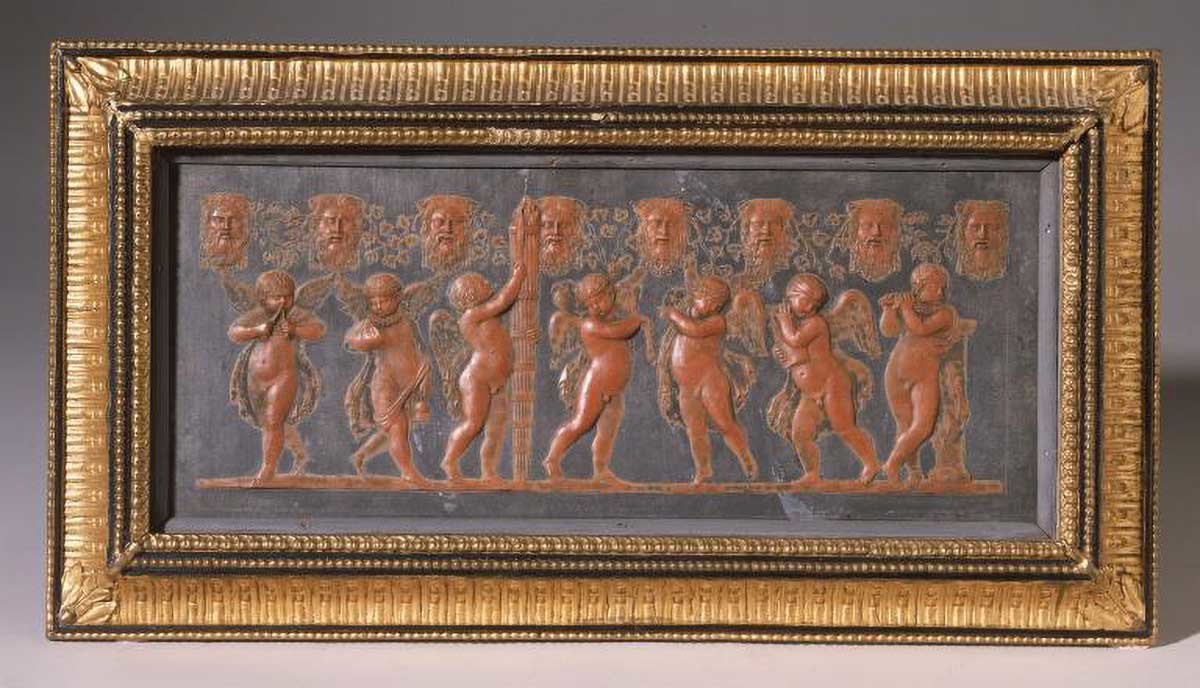

In Plato’s Pharmacy, Derrida pointed out that the Greek word pharmakon (remedy, poison, scapegoat) used by Plato in Phaedrus to prioritise speech over writing shows that meaning is always undecidable, always a trace of a trace. Words (signifiers), he said, refer to other words (signifiers) ad infinitum so we can never be sure which of the senses a writer intends; specifically which of the three senses of pharmakon Plato meant.

“Genius” is such a word: it too has many senses. Etymologically, genius is a derivative of the Proto-Indo-European gen(e)-yo, to “give birth to.” In this case, Derrida is a genius because his writings spawned works by many other people. However, according to his position that authorial intention is undecidable and readers are the writers of the meaning they find in the texts they read, he cannot be a genius. Any writings about Derrida’s work are actually by whichever reader is, while reading, writing her own meaning with Derrida’s words.

On a general level, a “genius” is an exceptional intellectual or creative person. While Derrida’s cerebral power is undeniable given his academic achievements and the contexts he worked in, thinkers like John Searle and John Ellis vehemently refused to assign any exceptionality to Derrida’s intellect.

They are likely to agree, however, that Derrida can be “genius” in another sense of the word: as a person who exerts a powerful influence, for good or bad, over others. Derrida—or rather what Derrida’s readers have written as they read his works—has indeed “exerted a powerful influence” over many across a wide range of disciplines (in literature, psychoanalysis, socio-linguistics or the arts) since the publication success of his books Writing and Difference, Speech and Phenomena, and Of Grammatology.

The latter—a linguistic, psychoanalytical, semiotic and phenomenological exploration of meaning through the relationship between speech and writing—is considered the seminal text for his theory of deconstruction. While Derrida was at pains to present deconstruction as indefinable, it may be plausibly described as a reading methodology that unpicks the whole with a part. That is, it demonstrates how to read like Derrida; i.e., to destabilise the authority of a text by challenging the received meaning of one word within it, and to enact how the lesser-known or ignored meaning of that one word (e.g. pharmakon) shifts and changes the meaning of the whole text (e.g., Phaedrus and its speech-writing, presence-absence binaries).

In Writing and Difference, Derrida sets out deconstruction through his readings of such bastions of Western intelligentsia like Levi-Strauss (anthropology), Hegel (philosophy) and Artaud (artist and writer). But in Speech and Phenomena, where he reads Husserl’s phenomenology and theory of sign in relation to rhetoric, logic, and language, Derrida gives philosophical readers hope that there was more to him than the twists, turns, and incorrigible circularity of his other publications. In Speech and Phenomena, Derrida offers cogent and enigmatic argumentations that justify his place in the contemporary philosophical cannon. Even his discussions of aporetic logic have led some to describe him as the intellectual equal of Kant (see Christopher Norris’ Derrida). Which is to say, according to Derrida, the readers who wrote those arguments as they read Derrida’s writing are the polymaths—like Kant’s readers (not Kant).

So as to conform to Derrida’s thought and form of argumentation, is it fair to say at this stage that there are some traces of madness but none of genius in Derrida?

Derrida the Charlatan?

Interestingly, both supporters and critics tend to refer to the same example to make their respective cases: Derrida’s presumption that his style of enactment is as legitimate a form of argumentation as the systematic reasoning of analytical philosophers like Searle.

Derrida’s style of enactment is his commitment to demonstrating, not stating his argument. Such insistence on enacting his points makes perfect sense: given that many of his core theories—différance, deconstruction, trace, undecidability, Il n’y a pas de hors-texte—are predicated on his positions that consciousness is never unmediated, that words are self-referential and free of intentionality, that language is unconnected to objects or reality, and that readers, writers, humanity “exist” in an unfixed and constantly deferred multiplicity and difference.

For countless Derrida fans, such ideas confirm his exceptionality. For his critics, they show him up as a charlatan. Etymylogically, a charlatan is someone who pretends to have knowledge or skill. In its derivation from the French and Italian ciarlatano, (from cialare: to babble), a charlatan is someone who sells “supposed remedies.” The Greek word for remedy is pharmakon, which is concurrently the word for poison that Plato used to describe writing. Poison is also inferred in the etymology of charlatan via “supposed.”

Let’s consider Derrida’s response to Searle who, in the spirit of dialogue, challenged Derrida’s reading of J.L. Austin on illocutionary acts. Austin is the founder of speech-act theory and speech-act theory is Searle’s expertise. Yet Derrida, thinking Searle in need of a masterclass in enactment, responded to Searle’s criticism by enacting his objections. That is, he chose words and formed his sentences on the basis of the etymological and classical (not contemporary) meanings of the words he used to demonstrate that he had not misunderstood speech-act theory or illocutionary acts (defined as what is said and intended) in the way Searle had suggested. Rather, Searle had failed to recognise the vocabulary of what he claimed to be his area of expertise (irrespective of the fact that Searle, an analytical philosopher, would never have imagined that Derrida would be referring to etymologies and not the plain senses of the words).

So, for Derrida and his supporters, Searle’s expertise was vitiated by the fact that Derrida had demonstrated that Searle did not know his own philosophical vocabulary at its etymological and classical depth. But what his supporters seem to have overlooked is that this public shaming of Searle was a stunning enactment of writing as pharmakon, i.e., Searle as scapegoat. More so because it seems to rather unwittingly reaffirm Plato’s point that the absence of the writer (Derrida using etymology to hide his intention) has obfuscated meaning for the reader (Searle).

Derrida: Madman, Genius, and Charlatan?

Clearly, then, Derrida is madman and charlatan to those who consider his work trivial and without philosophical depth, but genius to those who enjoy and find depth in his enactments. Or perhaps he is nothing of these things. Without doubt, he would disapprove of the title of this article and disparage its attempt to pin him to such labels.

What remains a persistent oddity, however, is his refusal to acknowledge the fundamental incoherence in his rejection of demonstrable meaning (which he never admits to totally abandoning). If he insists that Searle and others have misunderstood him, is he not concurrently confirming: (i) that he cannot disclaim authorial intention or reject fixedness in either writer, text, or reader; and (ii) that Plato’s prioritization of speech on the basis of presence and his subordination of writing because of the writer’s absence, was right all along?

But, as Foucault explained so well, these are stupid questions because, forgive the pun, there’s a method to the madness. “[Derrida] writes so obscurely you can’t tell what he’s saying … [because] when you criticize him, he can always say, ‘You didn’t understand me; you’re an idiot.’” And that, I suggest, is a crazily clever ploy.