Books are deeply embedded in what we refer to as human culture. They have been so since ancient times. However, one of the main developments that influenced how we relate to and work with books occurred during the 15th century when the German inventor Johannes Gutenberg developed the printing press prototype. The printing press changed book production deeply. What was before the press, a long and expensive process, became faster and accessible. Books were produced faster, and the printing press gave the middle-class access to books.

Who Was Johannes Gutenberg?

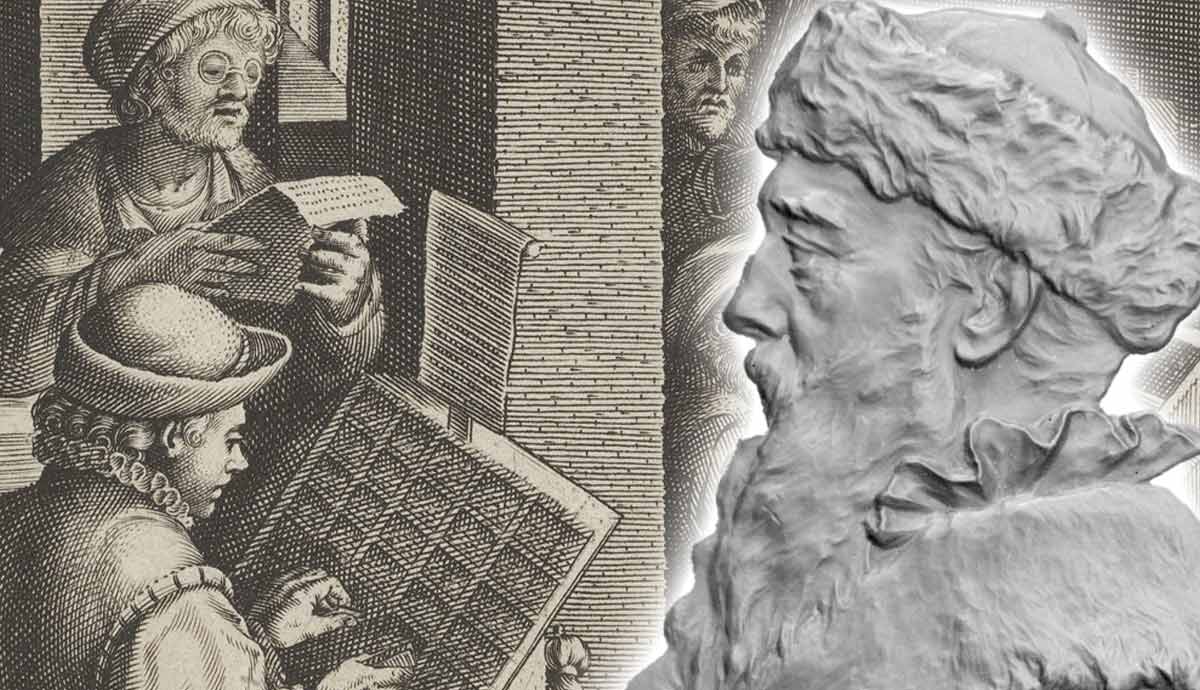

Johannes Gutenberg (ca. 1400-1468) is considered the main inventor of the printing press. He was born in Germany during the 14th century and worked as a craftsman and inventor. Unfortunately, both the life of Gutenberg and his process of inventing the printing press are not clear. Few documents can offer information regarding his early years. It’s only through some transactions and correspondence that we know most of the information regarding his activities.

He was the son of a patrician who seems to have been from Mainz. Besides this, transaction documents reveal that he was trained in metalwork, most likely from a young age. During the earlier stages of his career, we know that Gutenberg was exiled from Mainz. Most historians agree that this most likely happened between 1428 and 1430, when there were a lot of tensions between the guilds in Mainz. After being exiled, he moved to Strasbourg.

From 1444 onwards, his activity is recorded once again in Mainz, where he worked as a gem cutter, taking on students to train in this craft. Besides his official activities, Gutenberg is reported as having been involved in work that he kept secret from others. He most likely kept his inventions and prototypes secret because he feared that his ideas might be stolen.

The Historical Context of Johannes Gutenberg’s Invention

The invention of the printing press in Europe emerged in a historical context where manuscript culture was already well-established across most European countries. Before its arrival, the primary method of disseminating information to a wider audience was through the painstaking creation of handwritten manuscripts. This meant that a book had to be copied by hand, and this process of copying was usually undertaken in special workshops where individuals had undergone training as copyists and scribes. The practice of copying material in an orderly manner originated in medieval monasteries, where monks would be trained to do this. They would copy books from the monastery’s collection, and then these newly copied books could be kept or sold for extra income. The model of a copying workshop originated thus in this practice initiated by monks and entered the secular world once books became sought after.

During Gutenberg’s time, copying was happening in a secular setting, with workshops in most towns dedicated to this. However, because replicating the contents of a book was a laborious process, books weren’t accessible to everyone. The final price of the book was, most of the time, quite high for the common individual as it involved sourcing materials, paying the copyist, and then arranging for a proper binding of the book. Despite the problem of the price, books were highly valued by most city inhabitants and were seen as luxury objects that could prove someone’s status and erudition.

The First Printing Press

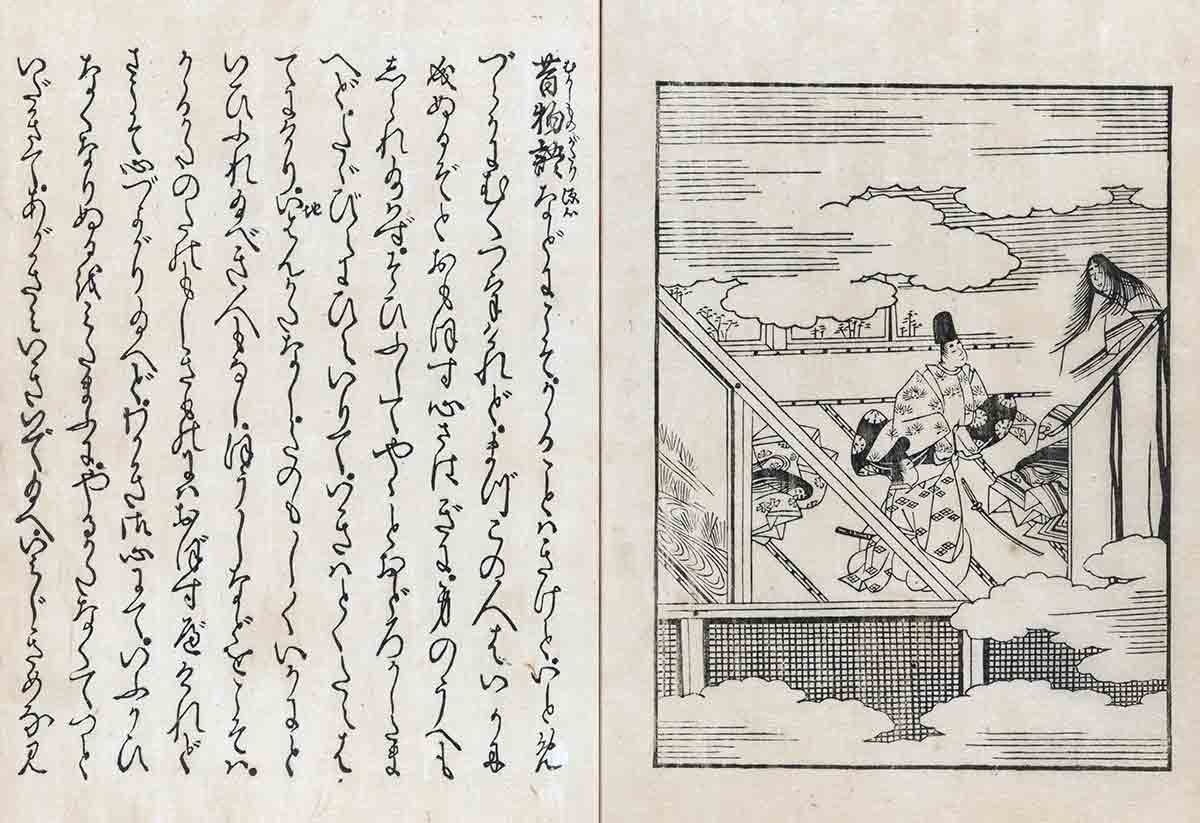

Although the common impression is that the printing press appeared for the first time in Europe, this assessment is inaccurate. For example, the oldest printed text, dating back to ca. 868 AD, was found in the Dunhuang area in China. The printing press that was most likely used to print this text involved pressing paper on hand-carved blocks with reverse characters. The blocks could be made out of wood or metal. During the 10th and 11th centuries, the movable printer was documented in China in the Hubei province. In the work Dream Pool Essays, we are told that the craftsman Bi Sheng molded moveable letters from clay, which he carved and then arranged on an iron plate. He preferred this method as clay didn’t absorb as much ink as wood did.

Despite Bi Sheng’s revolutionary inventions, it didn’t gain much popularity. In the 13th century, people in China used a printing press with wooden movable characters, while Korea adopted the metal movable type in the 14th century. Despite the many alternative methods of the movable press, these inventions in Asia were not met with the enthusiasm of Gutenberg’s press. They didn’t have wide usage and remained slightly isolated, while Gutenberg’s invention became widespread throughout Europe quite fast, changing the fate of manuscript workshops.

How Did the Gutenberg Press Work?

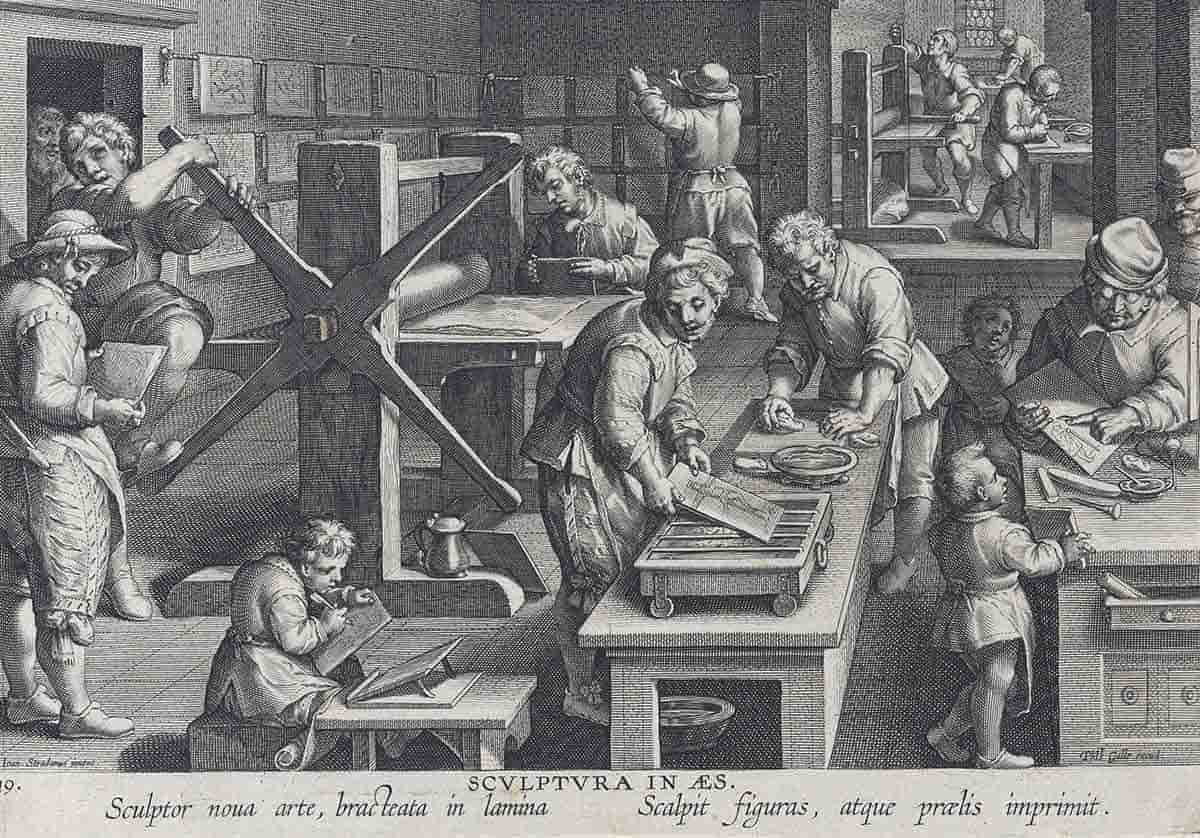

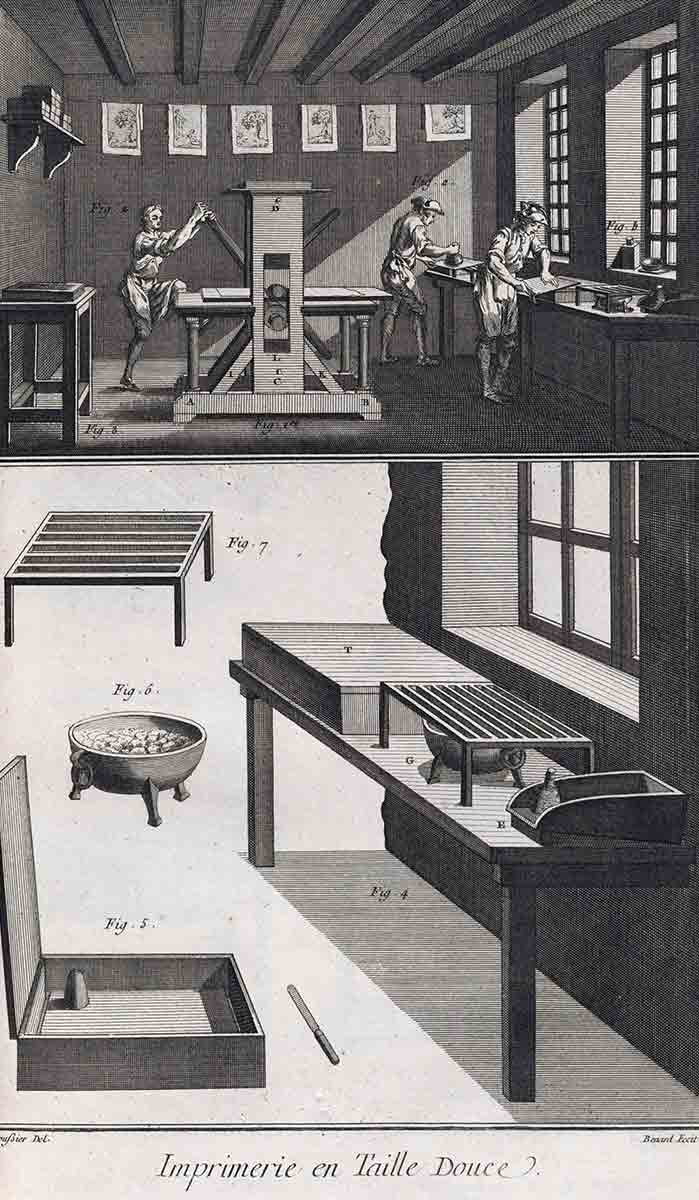

Gutenberg’s printing press featured a hand-moulded metal matrix for every necessary character. He used the moveable printing system to ensure a shorter production time because this made moving the letters around easy. Another important point of this printing press model was the use of a special ink which was developed to prevent smudging and the ink from running out too fast. The ink that Gutenberg opted for was a type of ink made out of linseed oil and soot. This helped the ink get fixed to the moulds that would then be imprinted on the paper.

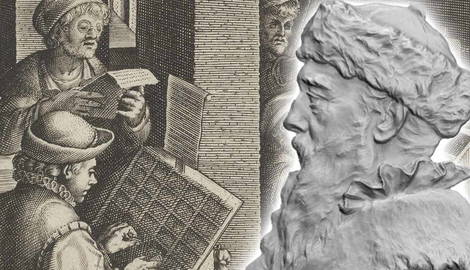

The process of producing a book was still a complicated one. An entire workshop would work to operate the press. The paper for the pages would be prepared and cut according to the size. Then, another person would make sure that the page of text to be printed would be fixed on the press frame. This would be done letter by letter to arrange the sentences on the page. Once this was done, someone else would verify whether the ordering was correct and according to the model. The final step would be to set the press and start printing. This process would be repeated for every page of the book. Finally, the book would be bound once the pages were dry.

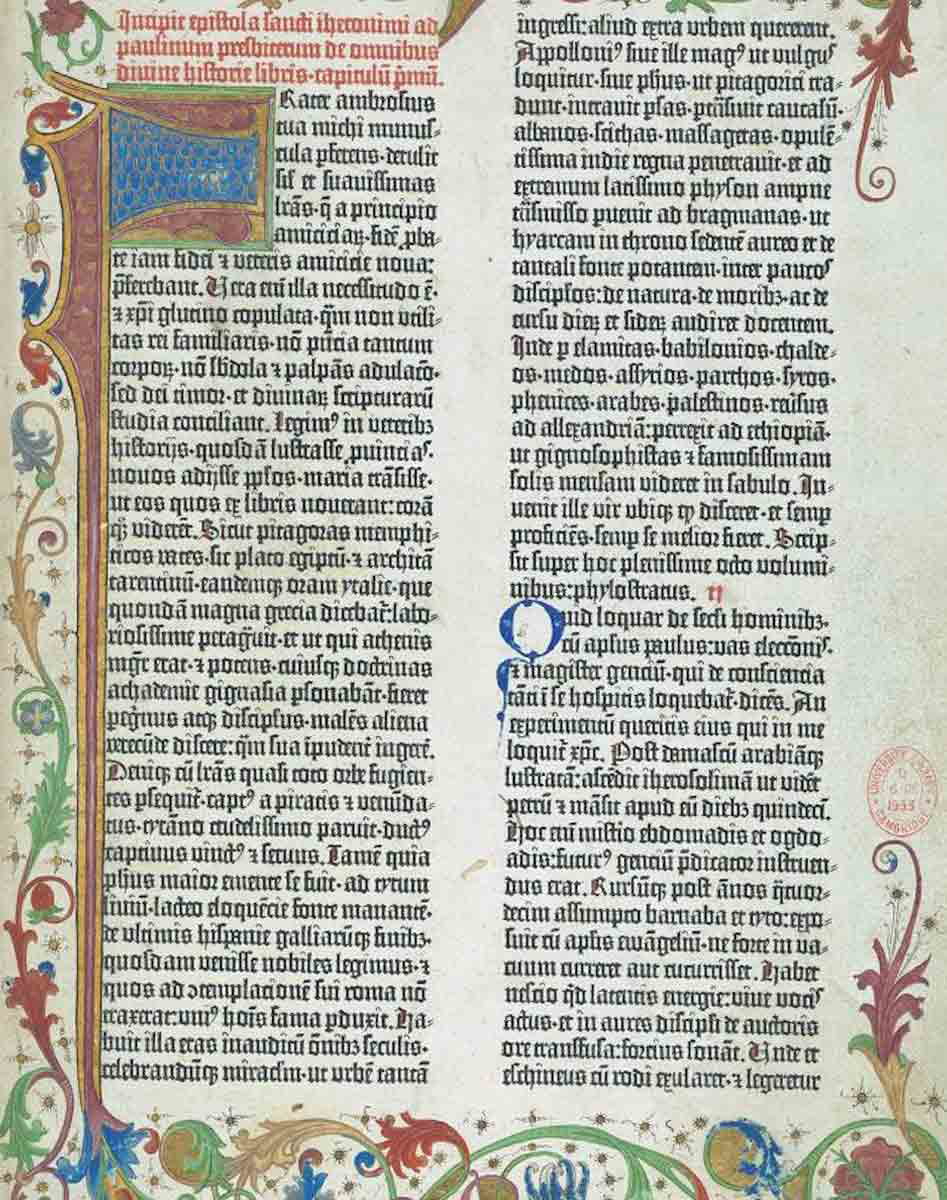

The first book which Gutenberg printed was the Bible. This project was financed by Gutenberg and Johann Fust (ca. 1400-1466). This Bible was an instant hit and it effectively launched Gutenberg’s press.

Patent Dispute: Gutenberg vs. Fust

The documents recorded Gutenberg back in Mainz in 1448 where he borrowed money from a relative for his printing press project. Only by the 1450s did his printing press prototype reach a level of functionality, making it an attractive venture for others besides Gutenberg. As briefly mentioned before, the prototype attracted the attention of Johann Fust, who became a money lender for Gutenberg’s press. He lent around 800 guilders, which was a substantial sum at the time. To make sure that his money would be returned, Fust agreed to lend the sum only if the printing press and all related tools acted as collateral. Besides this initial sum being lent, Fust is reported to have invested another 800 guilders a few years later. This time, not as a sum to be borrowed but as an investment to make him a partner in the print business.

Fust’s association with the printing press business became an important factor that led to the dispute between Fust and Gutenberg. After investing 1,600 guilders in the prototype, Fust grew impatient and wished to get his investment back as profit. After all, the printing press had the potential to generate that type of profit. Unlike Fust, Gutenberg was keen on perfecting the prototype even further to make sure it reached its best possible technical form. This made Fust sue Gutenberg, eventually winning the process against the inventor. This meant that, according to the initial terms, Gutenberg had to hand the printing press and the tools.

The Gutenberg Press Under Fust

Unfortunately, it is uncertain why the trial between the two ended as it did. Some historians believe that the number of printed Bibles should have covered Fust’s investment and, therefore, provided the means for this dispute to be settled peacefully. However, this wasn’t the case, as the printed books that Gutenberg owned were not taken into account as part of his property. Due to this, he lost the printing press to Fust. As odd as it may seem today, when the trial took place, there was no legal framework for dealing with printed material. It was a new type of object that could not be readily classified by the existing laws.

After the settlement, Fust became the possessor of the printing press. The other title printed beside the Bible was a Psalter, which was also quite successful. In order to keep on operating Gutenberg’s workshop, Fust hired his son-in-law Peter Schöffer who was skilled with the printing press. Schöffer was used to the process because he was one of Gutenberg’s best workers. Interestingly enough, Schöffer also acted as a witness against Gutenberg during his trial with Fust. Because of this animosity, the Psalter only mentions the two men as makers and has no mention of Gutenberg or his contribution on the first page. The Psalter was popular because it imitated the decorations of a manuscript, with two-color initial letters and beautiful decorative page borders.

The Historical Impact of Johannes Gutenberg’s Model

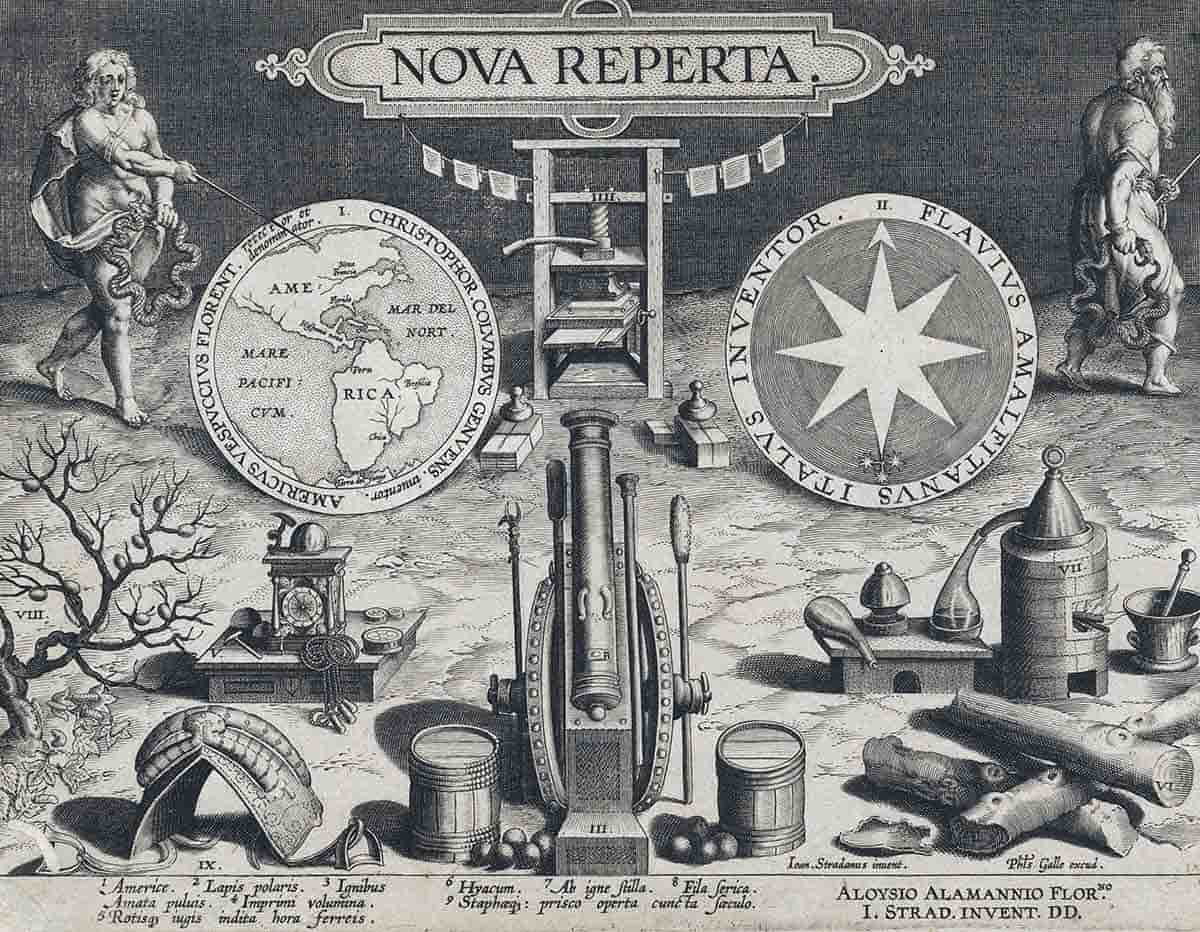

The invention of the printing press in Europe changed how information traveled. The importance of Gutenberg’s press is visible from its success in the decades and centuries following its invention. This fast-paced change in how information was reproduced and shared stirred excitement and fear in those witnessing its rise. Among those who were worried about the possible negative effects of the printing press the Catholic Church was one of them. For example, Pope Alexander VI threatened to excommunicate those who would print books without the Church’s approval, fearing that this might lead to heresy. In part, he was right. After all, it was the rise of the printing press that enabled the Reformation to spread so quickly and successfully almost a century later under Luther and Calvin.

Despite this, there was enough enthusiasm to support and use the new technology. After all, pillars of scientific discovery like Copernicus or Galileo printed their work instead of writing it in manuscript form. Because of the printing press, most of Europe got to read Copernicus’ important theory on the movement of heavenly bodies, changing science forever. It’s also in print that Newton’s discoveries became widespread and debated around the continent, and the importance that the printing press held for knowledge is still visible today. We owe the idea of publishing books to this entire process of the printing press’ creation in both Asia and Europe.

When talking about Gutenberg’s historical importance, it’s difficult to mention all the ways in which the printing press changed the world. The trial between him and Fust was also an important element in popularizing the invention through the controversy it created. Moreover, it was also the first trial where the judges had to decide how to judge printed paper, thus creating a precedent for future laws involving copyright and printed material.