Of all the early medieval Anglo-Saxon kings, King Octa is not a particularly famous one. Nevertheless, he intrigues scholars of this early period for several key reasons. For one thing, there is conflicting information surrounding when he ruled and the identity of his father. In fact, his placement in the list of kings of Kent is unclear. Furthermore, he is used as a chronological anchor point in an early Arthurian record. This means that the uncertainty surrounding King Octa also impacts the question of when King Arthur was supposedly active.

Who Was King Octa of Kent?

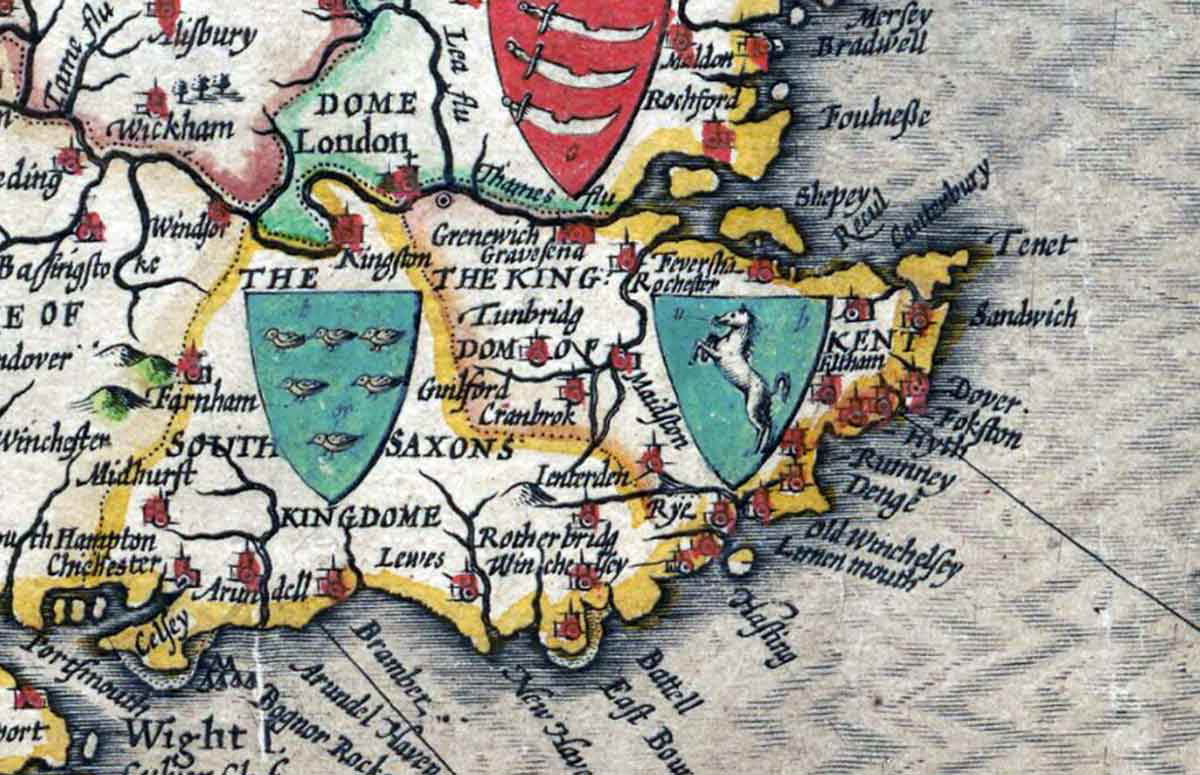

Firstly, let us consider King Octa’s basic profile. He was a king of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Kent in southeast England. This kingdom was one of the earliest Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Britain, and Octa was one of its earliest kings. Hence, we can understand why he should have been an important figure in this early medieval period. His reign followed, possibly directly, King Hengist himself. This was the king who had led the Anglo-Saxons to Britain in the first place. As one of Hengist’s close successors and also someone from that same dynasty, Octa should have been very important indeed.

Nevertheless, few Anglo-Saxon sources mention Octa directly. In fact, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle does not mention him at all. This does not mean that he did not exist, since that chronicle generally gives little attention to the kingdom of Kent after Hengist’s death. It does, however, mean that we do not know much about him.

What Is the Conflicting Evidence for King Octa’s Father?

When we look at the references to Octa in Anglo-Saxon and British records, we see that there are fundamentally two conflicting traditions. One of these traditions is that Octa was the son of Hengist and was his successor. On the other hand, the other tradition affirms that Octa was the son of Oisc, son of Hengist. This makes Octa the grandson of Hengist and his second successor rather than his immediate successor.

For example, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle of the late 9th century presents Oisc as the son of Hengist and simply does not mention Octa. On the other hand, the Historia Brittonum, which dates to earlier in the same century, calls Octa the son of Hengist and presents him as his successor. This has a big impact on the chronology of his reign. Depending on which version is correct, this would result in a difference of about a generation, or approximately 20 or even 30 years, which is a substantial amount.

Why Is Octa Important to Arthurian Studies?

One of the reasons that unraveling the mysteries surrounding King Octa of Kent is so important to some is that the date of his reign impacts Arthurian studies. The earliest surviving source that gives an overview of King Arthur’s career is the Historia Brittonum. This was written in c. 830. This document famously assigns 12 battles to Arthur, the last of which is the Battle of Badon. For all the debate that exists over Arthur’s very existence, little progress can be made without understanding when he was supposed to have lived. Otherwise, it is difficult to assess how well his alleged activities conform to the archaeological evidence or other documentary evidence.

With this in mind, it is highly significant that this early record of Arthur’s career directly connects him to the reign of Octa of Kent. This Anglo-Saxon king is mentioned in the Historia Brittonum in the sentence immediately preceding the one which introduces Arthur.

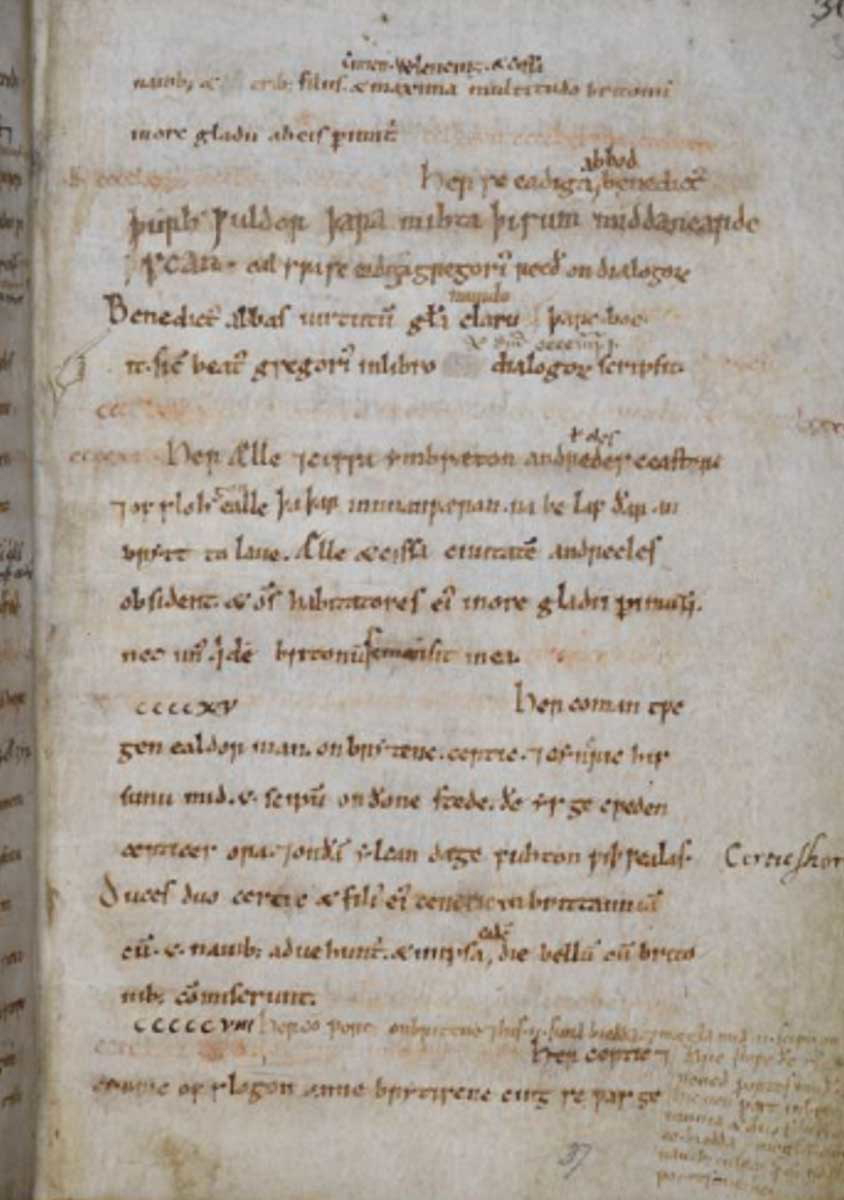

The passage in question reads:

“On Hengest’s death, his son Octha came down from the north of Britain to the kingdom of the Cantii, and from him are sprung the kings of the Cantii. Then Arthur fought against them in those days, together with the kings of the British, but he was their leader in battle.”

The “kingdom of the Cantii” is the kingdom of Kent. In other words, this passage tells us that after Octa became the king of Kent, Arthur began fighting against the Anglo-Saxons. This does not necessarily mean that his campaigns against them began immediately after the start of Octa’s reign, but they evidently started not long afterward. Hence, establishing when Octa’s reign began is very relevant to the question of when Arthur lived. It is ironic that, just as Arthur is famously surrounded by mystery, so too is this Anglo-Saxon king who could otherwise have been an excellent anchor point for the Arthurian legends.

What Does the Earliest Evidence Reveal About Octa?

What, then, do the earliest records really reveal about King Octa of Kent? Although the available evidence is contradictory, can we come to any reasonable conclusions? Let us start with the basic question of Octa’s lineage. Was he the son of Hengist and father of Oisc, or was he actually the son of Oisc and thus the grandson of Hengist?

While no smoking gun definitively proves one conclusion over another, considering which view is supported by the earliest evidence is highly important. The English historian Bede makes Octa the son of Oisc, the son of Hengist. Given that Bede is the earliest source of information about Octa, this is surely significant. Bede wrote his Ecclesiastical History in about 730, significantly earlier than the composition of the 9th-century Historia Brittonum. With such a large chronological advantage, it makes sense to prefer Bede’s information. Hence, on this basis, it seems more likely that Octa was indeed the son of Oisc, not Hengist.

Does this information tie in well with other early evidence? Let us consider the fact that the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us that Oisc became king of Kent in 488 and that he ruled for 24 years. This would mean that his reign ended in about 512. If Octa had been his successor, this would mean that Octa’s reign would have begun that year. On the other hand, placing his reign before Oisc would mean that he would have reigned before 488.

The Historia Brittonum places the reign of Octa after the death of Saint Patrick. This figure’s death appears to have occurred in the 490s. Hence, despite calling Octa the son of Hengist and presenting him as Hengist’s successor, this record supports the conclusion that his reign came after Oisc’s, not before.

Furthermore, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, another one of the earliest sources, makes Oisc the son of Hengist. The weight of this early evidence, even including the Historia Brittonum, clearly supports making Octa the grandson of Hengist rather than his son.

There is another factor to bear in mind. The traditional date of the Anglo-Saxon arrival is about 447, based on Bede’s calculations. However, more contemporary evidence indicates that this arrival actually occurred in c. 428. This is evident from the Gallic Chronicle of 452, the Life of St Germanus, and archaeological evidence. All sources agree that Hengist was the ruler who led this initial arrival, invited by Vortigern in the 4th year of his reign.

We can assume that Hengist was at least in his twenties at the time of this arrival, meaning that he must have been born near the beginning of the 5th century. This would make him nearly 100 years old by the time of the death of Patrick. As already mentioned, the Historia Brittonum places Octa’s reign after Patrick’s death. Although not impossible, this would make it very unlikely for Octa to have been a son of Hengist. Making him a grandson of Hengist is, by far, the more satisfying chronological scenario.

What Do We Really Know About Octa of Kent?

In conclusion, there is conflicting evidence concerning King Octa of Kent. Some sources present him as the son and successor of Hengist, whereas others present him as the son and successor of Oisc, son of Hengist. However, the evidence strongly suggests that Octa was, in fact, Hengist’s grandson. This is evident from an examination of the earliest sources. Bede, the very earliest source that mentions these figures, clearly presents Octa as the son of Oisc.

The Historia Brittonum, which appears to be the next earliest source, presents him as Hengist’s son but places him after the death of Patrick. This supports the conclusion that he was Hengist’s grandson since the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, closely following the Historia Brittonum, places Oisc’s reign earlier than Patrick’s death. It also explicitly makes Oisc the son of Hengist without mentioning Octa. Hence, the weight of these early sources firmly supports the conclusion that the lineage given by Bede is the correct one. This would mean that King Octa of Kent began his reign after Oisc, who apparently reigned from 488.