When we think of medieval philosophy, we often encounter the stereotype of an area void of any knowledge, as if philosophy and science did not exist throughout this period. While plenty of medieval philosophy was overshadowed by theology, philosophy arguably developed into a new form because it was put in service of religion. The most recognizable figures from the period are St. Augustine of Hippo and St. Thomas Aquinas. However, in this article, we take a closer look at lesser-known medieval thinkers who have not received their due attention.

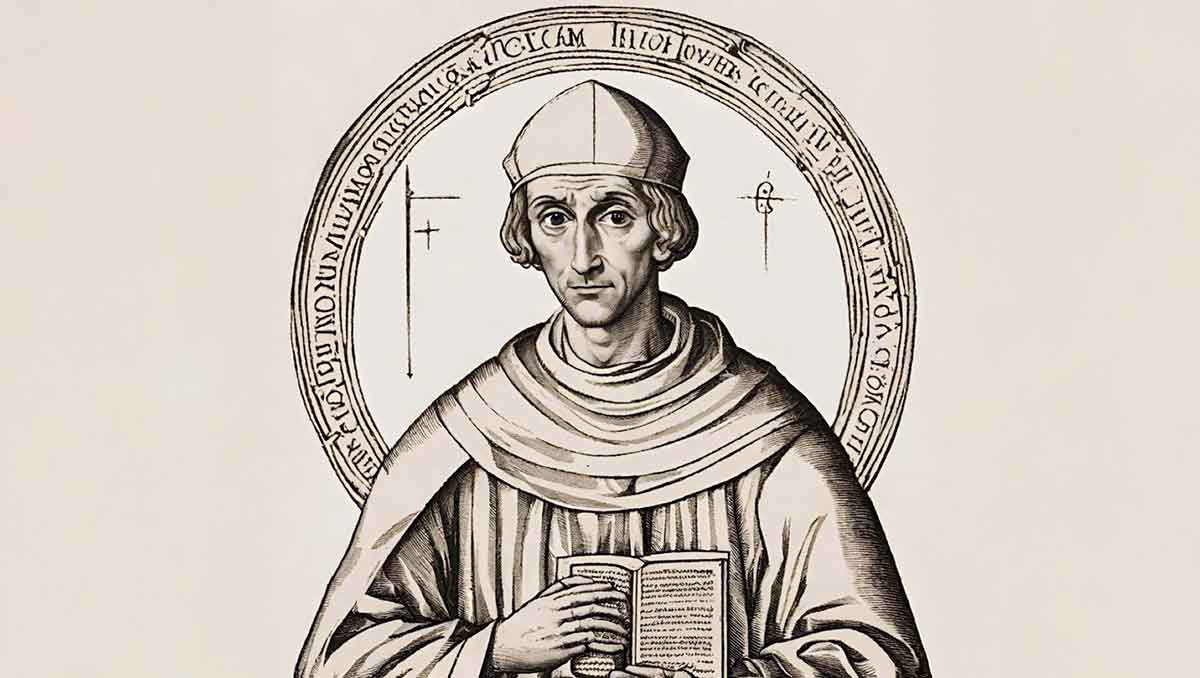

1. Tertullian

Tertullian was an early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa and is considered to be one of the first Christian authors who wrote in Latin. He studied the Christian doctrine closely but also examined a lot of Greek philosophy, as he wrote extensively on different philosophical topics.

In Tertullian’s philosophy, we can notice an immense influence from Stoic philosophy, especially Stoic materialism—the notion that everything that exists is made out of material matter. Just as the Stoics claimed that everything surrounding us is material, Tertullian also states that everything that exists, including God, is made out of material matter. He said:

“Everything that exists is the material existence. There is no such thing that lacks material matter, except the non-existent.”

However, it is important to mention that there are a lot of instances where Tertullian contradicts himself when it comes to materialism. For example, some interpretations of his work suggest that in his book Apologia he gives certain statements that oppose his materialistic philosophy, especially when writing about the nature of the soul. So, the question remains an open discussion of whether his philosophy is materialistic or idealistic.

But even though his materialistic view is an important aspect of his philosophy, he is most widely known for his saying “Credo quia absurdum est” or “I believe because it is absurd.” But what does that mean exactly? Well, Tertullian was a great believer in God and he stood out as a fierce defender of Christianity. He thought that even though philosophy had a great deal of wisdom, the real wisdom lies in the doctrine of Christianity—the Holy Bible and the Gospels. That is why he thought that there was no need for investigation and examination of the world after the Gospels. Because he stood strongly in defense of Christianity, he is considered to be the first Apologetic—a movement defending Christianity and the faith in God against rational critique.

His famous quote “I believe because it is absurd” is a direct response to the rational critiques that were present. He thought that faith transcends the bounds or scope of human reason and logic. There is no need to look for proof of God’s existence, he said. Even though it may be absurd to say that, Tertullian still chose to believe rather than be a non-believer. The quote would later be reformulated by St. Augustine of Hippo via his saying “Credo ut intelligam” or “I believe in order to understand.”

2. Boethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known simply as Boethius, was a Roman historian and philosopher of the Early Middle Ages. He was a central figure in the translation of the Greek classics into Latin and that is why he is considered as being the first one to revive philosophy in the so-called Dark Ages.

In his philosophy, we can notice that Boethius is under great influence from ancient philosophy—Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics. In contrast with other thinkers from the period, Boethius found more wisdom in philosophy than in the Holy Bible, in an era when philosophy was put in service of theology. That is why his philosophy has an eclectic character. His most significant work is On the Consolation of Philosophy, in which he makes the case as if he has a dialogue with philosophy. But he examined religious topics as well. For example, he was strongly opposed to the view that the Holy Trinity should be divided into three, but instead, he promoted the idea of their unity. However, even though he examined theological topics, he mostly contributed with his philosophical insights.

When it comes to his epistemological stances, Boethius can be classified as a relativist and a skeptic. He thought that humans cannot reach absolute knowledge but that our knowledge can only be relative. Because it is relative, Boethius thought that it is uncertain and therefore limited. So, he concluded that it is only God that can possess absolute knowledge and no matter how much or how hard we try to achieve that level of knowledge, it still remains a mission impossible.

Boethius recognizes four sources of knowledge. The first one is the sensual experience—this is the ability to perceive through our senses. Perception further helps in the creation of the second source of knowledge, which is representation. After the representation of the object has been created it enters our reason and our rational thinking. In the end, everything ends up in the mind as the final destination for all knowledge that we gain. This is the path about how we acquire knowledge in the world, says Boethius.

3. John Duns Scotus

Duns Scotus was a Scottish Catholic priest, university professor, philosopher, and theologian. He is considered to be one of the four most important Christian philosophers of Western Europe in the High Middle Ages, together with Thomas Aquinas, Bonaventure and William of Ockham.

First, let us examine his epistemology. Scotus starts off by saying that human knowledge has its roots in empirical sources – in our senses. This would mean that humans do not have any a priori ideas, which is why Scotus said that the human being is tabula nula, an argument that would later be further developed by John Locke and his idea of tabula rasa. When it comes to the ultimate sources of our knowledge, Scotus states that there are two types of knowledge: intuitive and abstract (or reasonable knowledge). The intuitive knowledge provides us with awareness of the objects in the world, of their real active existence and presence. Thus, intuitive knowledge directly investigates the objects in the world.

On the other hand, abstract knowledge comes into play when we are trying to make a statement about what is a common trait of the multitude of particular objects. In a way, abstract or reasonable knowledge tries to bring all shared traits of particular distinct objects together. That and only that is the real power and strength of abstract knowledge. Having this opinion, Scotus states that reason also has its roots in the senses and experience and because of that, intuitive knowledge reigns supreme.

Another important characteristic in Scotus’ philosophy is that he is strongly opposed to the philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas. Scotus makes a clear distinction between philosophy and theology. He thought that the theological dogma cannot be a subject of investigation of abstract or reasonable thinking, as opposed to Aquinas who tried to give a reasonable foundation to belief. Also, Scotus thought that theology is a practical science, as opposed to Aquinas’ opinion that theology is a theoretical and practical science at the same time. Scotus also opposes the idea that God can be a subject of metaphysical examination. Instead, he thought that metaphysics can only give us knowledge of God a posteriori (after experience).

4. William of Ockham

William of Ockham was an English scholastic philosopher, author, apologist, and Catholic theologian. He is considered to be a key thinker from the medieval period and was also at the center of the major intellectual and political controversies of the 14th century.

Ockham grounds all our knowledge in experience and thinks that experience is the root source of all gained knowledge. Just like Scotus, Ockham thought that the most valid and accurate knowledge is the one that we have gained through intuition, which directly correlates to experience, since intuitive knowledge is directly linked to knowledge of particular objects in the world. So, just as Scotus did earlier, Ockham rejects the notion of there being ideas that we are born with (a priori ideas), i.e. ideas that are completely detached from any gained experience or any sensual knowledge. Throughout his work, we can sense that he was greatly influenced by the philosophy of Duns Scotus as well as Aristotle, even though he never admitted this.

But Ockham does not stop there when talking about intuitive knowledge. Instead, he goes on to say that intuitive knowledge can even be caused by God. Because God’s Being is powerful, He has the ability to give us an intuition or a knowledge of the world. But He cannot give us knowledge of an object that is existent, he can only give us knowledge of objects that do not exist, and through that, we can gain knowledge about the things that do exist. And this is the abstract knowledge or the abstract thinking that Scotus talked about. So, it is through abstract knowledge that God helps us—He helps us by showing us the things that do not exist and through that, we can confirm the things that do in fact exist.

Another important aspect of Ockham’s philosophy is his clear distinction between theology and philosophy. Ockham’s contributions to this debate are immense because he fought fiercely for philosophy to gain its independence at a time when reason was put in the service of theology. He does that by making a distinction between truths of reason and truths of faith. These two are totally separate, says Ockham. Reason considers all dogmas and arguments of faith to be absurd, which is why theology is full of dogma while philosophy contains all proofs and factual verifications. Thus, Ockham concluded that theology can never be a science because it cannot be proven logically.

Ockham is best-known for the concept of Ockham’s Razor. Ockham’s razor is a principle that suggests that when faced with a complex situation or an explanation for a phenomenon, the simplest one—requiring the fewest assumptions—is usually the best. Ockham came up with the principle when disputing metaphysical concepts because he noticed that philosophers tend to complicate things without a valid reason. That is why he suggested that when evaluating metaphysical claims, it is necessary to avoid entities or assumptions that cannot be verified. If we were to define Ockham’s razor in the simplest way possible we would probably have to say that “Entities should not be multiplied beyond necessity.”

5. Meister Eckhart

Meister Eckhart was a German Catholic priest, theologian, and philosopher. His philosophy was greatly influenced by Thomas Aquinas, Plotinus, and St. Augustine. One of his most popular claims is that God does not exist outside of this world but instead, He resides in the soul of human beings. Another differentiating characteristic of his philosophy is his teaching about the soul.

According to Eckhart, the soul has one part that is eternal, and is therefore not created because it has existed forever. That eternal part of the soul is the mind, and it is the mind that makes the human being a divine creature, says Eckhart. However, the mind is not the central station where the human being unites with God. The unity with God is established in the deepest point of his soul. But the unity with God does not mean that all differences between the human and God are gone simply because they have united. In fact, Eckhart says that those differences still remain. He compares this unity with the fall of a drop of water into the ocean. Even though the drop unites with the ocean and completely embraces the vast body of water, the ocean does not do that in return.