Are people born with empty minds that experience fills up like a blank sheet of paper? Or do they come into the world with some knowledge already in their heads? One influential Enlightenment thinker, John Locke, believed the former. His radical notion of Tabula Rasa, or “blank slate,” proposed that our minds begin as empty vessels and are formed by our experiences and what we learn from them. This idea not only challenged prevailing beliefs at the time but also set the stage for modern psychology and education.

The Origins of Tabula Rasa

Tabula Rasa means “blank slate” in Latin. John Locke came up with this term during the 1600s. He wanted to challenge the old idea that people know things when they are born.

Locke believed human brains are not pre-loaded with information. He said they are like empty sheets of paper. As we go through life, our experiences—things we see, hear, smell, taste, and touch—get written on them.

But Locke wasn’t the first person to think along these lines. Aristotle, the ancient Greek philosopher, had made a similar point many years earlier. In one of his books, De Anima, Aristotle called the mind an “unwritten tablet.” By this, he meant that all our knowledge comes from what happens to us as we grow.

This was very different from what his own teacher, Plato, believed. Plato argued that when people are born, their minds already contain knowledge from even before they were alive. That is because their souls have lived through many previous lives.

Additionally, the idea of the mind being blank originally came from scholars during medieval Islam, such as Avicenna. These thinkers studied what it means to have a soul and debated whether we are born knowing certain things.

Locke built on their work to create Tabula Rasa while writing about how people understood the world during an important period called the Enlightenment. His thoughts have continued to capture attention over centuries, making us think again today about how we learn at school—or anywhere else.

Locke’s Theory of Knowledge Acquisition

John Locke was an original empiricist who changed our perception of human thought by arguing that it all comes from what we experience. He believed when we are born, our minds are like blank sheets of paper. Everything we learn comes from things we see, hear, smell, touch, or taste.

This way of looking at knowledge—called empiricism—means our senses enable us to gain an understanding of the world around us. However, for Locke, it was not just what goes into our minds from the senses that mattered. It was how we then reflect on it.

He said there were two main ways this reflection happened: through sensation and reflection. Sensation is when we directly have an experience, such as feeling the warmth of a fire or hearing music. Reflection in this context does not mean looking at yourself in a mirror! It is about thinking further. For example, why do I feel good when the sun is shining warm on my face?

Locke disagreed with innatism, an idea supported by thinkers such as Descartes. Innatists believe some ideas—for example, those about God or math—are built into us when we are born. Locke thought this was nonsense. He said even complex ideas are made up of simple things we see and think about.

For instance, take the concept of “beauty.” This isn’t something we’re born knowing about. Instead, it’s put together by our minds when we reflect upon harmonious colors, shapes, etc.

The debate over whether complex ideas develop from experiences (empiricism) or are already there at birth (innatism) still rages today. Its effects can be seen in schools’ different teaching methods or how we understand growing up.

Implications for Human Nature

Locke’s theory of Tabula Rasa holds profound consequences for how we understand human nature—particularly when it comes to developing our morals and ethics. If the mind is indeed a blank slate at birth, then it follows that morality isn’t something we’re born with. It must be shaped by our experiences.

For Locke, this raises questions about whether children can be said to be good or evil in themselves. Instead, he would argue they acquire these values, teachings, and behaviors from their environment.

For example, does a child learn what is fair from an inbuilt sense of justice? No, it develops as they grow by watching those around them—the same goes for empathy.

Such ideas have direct implications for education and socialization if one’s mind starts out like a blank whiteboard. It suggests that these things can make people who they are (from being “nurtured” into kindness or intelligence), which has major implications regarding schooling and so on.

On the flip side, damaging environments may result in undesirable characteristics. Consequently, Locke stresses how important society is when shaping an individual’s beliefs and character—a view that lies at the heart of one of the oldest intellectual disputes of all time: nature versus nurture.

Here, Locke is firmly in camp nurture. He believes that what makes us comes not so much from our genes but from our experiences of the environment into which we happened to be born—and things like education along the way.

Criticisms of Tabula Rasa

Critics—especially rationalists and nativists—have raised important objections to Locke’s Tabula Rasa theory. They say some knowledge must be innate, not learned.

Among them were philosophers such as René Descartes. They believed the human mind contains built-in information about maths, logic, and morals that do not come from experience.

Universal truths like “2 + 2 = 4” fall into this category: these facts are part of our make-up. We do not need to be taught them. Locke’s suggestion that everything we know comes from our senses would have to be reconsidered if this were true.

In recent years, further complications have arisen from research in neuroscience and psychology. Although it seems clear that much of what we know comes from experience, it also appears that there are some things (cognitive abilities) with which we are born—or which develop very early indeed.

Research into how babies think has shown that even the youngest children have an elementary grasp of morals, numbers, and physics—ideas often thought to be beyond their comprehension. This suggests there are some things we don’t need to learn: they come naturally to us.

Locke had good answers to this sort of point, though. He said what looked like something you’re born with could equally well be caused by experiences you can’t remember having.

Although our minds start off empty at birth, they don’t stay that way for long. As soon as they begin to take stuff in through senses like sight or touch (which let them see or feel things), new thoughts can be formed based on these inputs alone—or on thoughts already there.

Tabula Rasa in Modern Thought

John Locke’s theory of Tabula Rasa had a profound influence on Enlightenment thinking, with thinkers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and David Hume following in his footsteps. These individuals adopted Locke’s ideas about the importance of experience, education, and environment in human development.

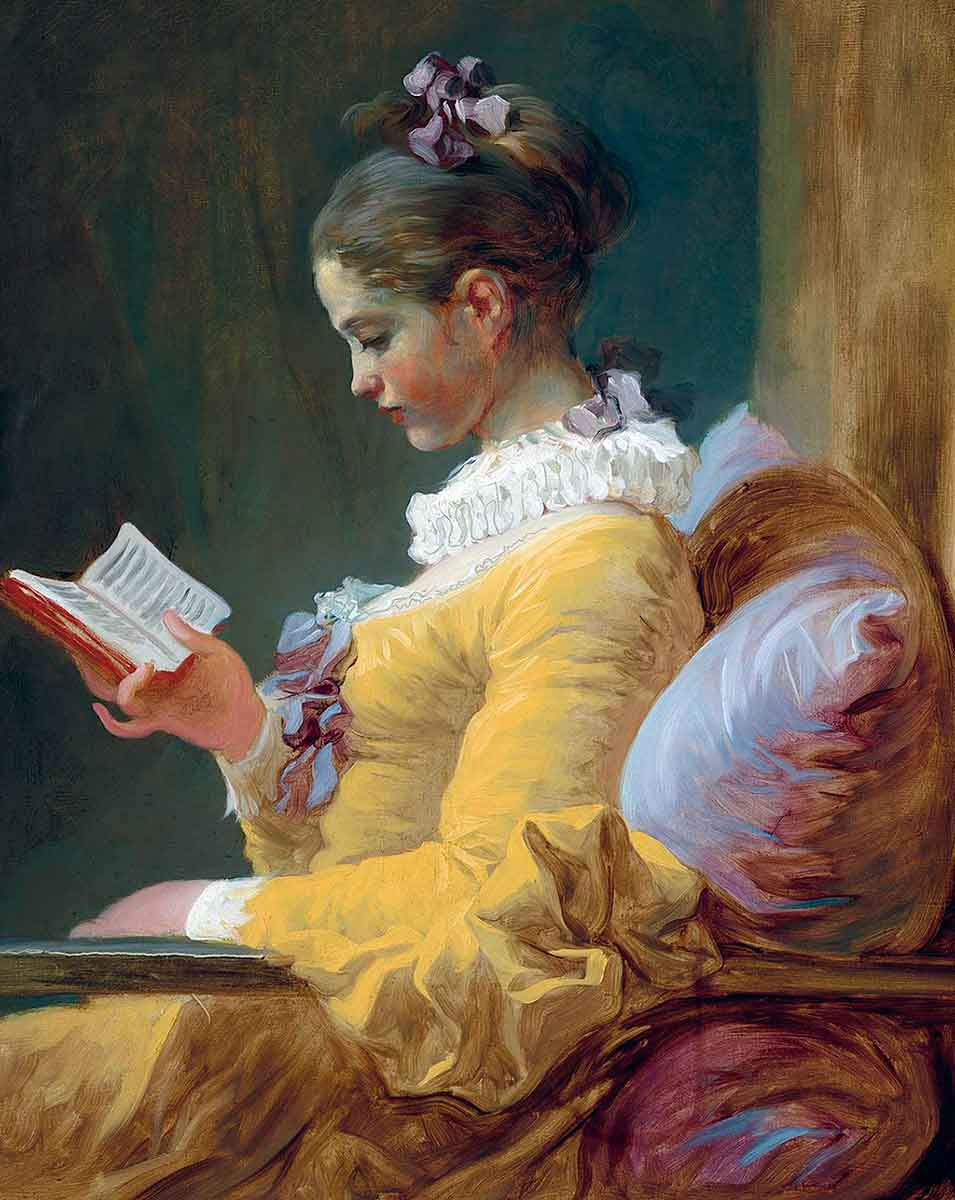

For instance, Rousseau argued in Émile that children should be educated in ways that allow their natural goodness to flourish—a concept that reflects Locke’s belief in the transformative power of education.

Tabula Rasa also continues to shape educational practices today. The notion that our minds are molded by experience finds support in everything from Montessori schools’ emphasis on hands-on learning to broader notions like “experiential” education itself (which simply means learning through doing).

Meanwhile, within psychology and neuroscience specifically, Lockean theory still fuels ongoing discussions around topics like nature versus nurture.

Although contemporary neuroscience recognizes genetic factors, it also emphasizes the crucial importance of experience in shaping the brain. The notion of neuroplasticity—how the brain adjusts itself based on experience—mirrors Locke’s idea of the mind’s flexibility, keeping his thinking pertinent in light of new scientific findings.

Are We Truly Blank Slates?

Did John Locke have it right when he said we were born without knowledge and everything we learn comes from experience? Or is the truth more complicated?

Today, science says Locke probably didn’t have it completely correct—even though recent research in genetics and brain science shows that we do not arrive in the world as blank slates. It turns out babies already know some things.

But that doesn’t mean the 17th-century philosopher was totally wrong. To understand how people develop, we need to look at both what they’re born with and how these biological predispositions interact with further life experiences.

Although genetic predispositions can give us a basic foundation—like a blueprint—it is our experiences that craft the specifics of who we are. A baby may have a natural talent for music, but if they never hear any or don’t practice, that potential may remain dormant.

So does this mean we’re all blank slates? The truth lies somewhere in between. We’re not wholly programmed by genetics or entirely malleable either. Rather, human development is an ongoing negotiation between nature (genes) and nurture (experience).

Tabula Rasa continues to be a powerful metaphor, reminding us that while our beginnings aren’t empty vessels (blank slate), what happens to us does help shape our life story enormously.