Lord Charles Cornwallis will forever be remembered as the British commander defeated at Yorktown, the last major battle of the American Revolution. Yet, the focus on this event obscures Cornwallis’ accomplished career as a general, diplomat, and administrator in the late eighteenth-century British Empire. Indeed, many scholars, including Richard Middleton and Chaim Rosenberg, believe Cornwallis played a significant role in establishing the foundation for British imperial power in the nineteenth century, particularly in India. Napoleon respected Cornwallis’ military, administrative, and diplomatic talents. Moreover, as Rosenberg notes, Cornwallis trained and influenced a generation of British officers and imperial administrators, including Arthur Wellesley, the first Duke of Wellington.

Lord Charles Cornwallis: Early Years

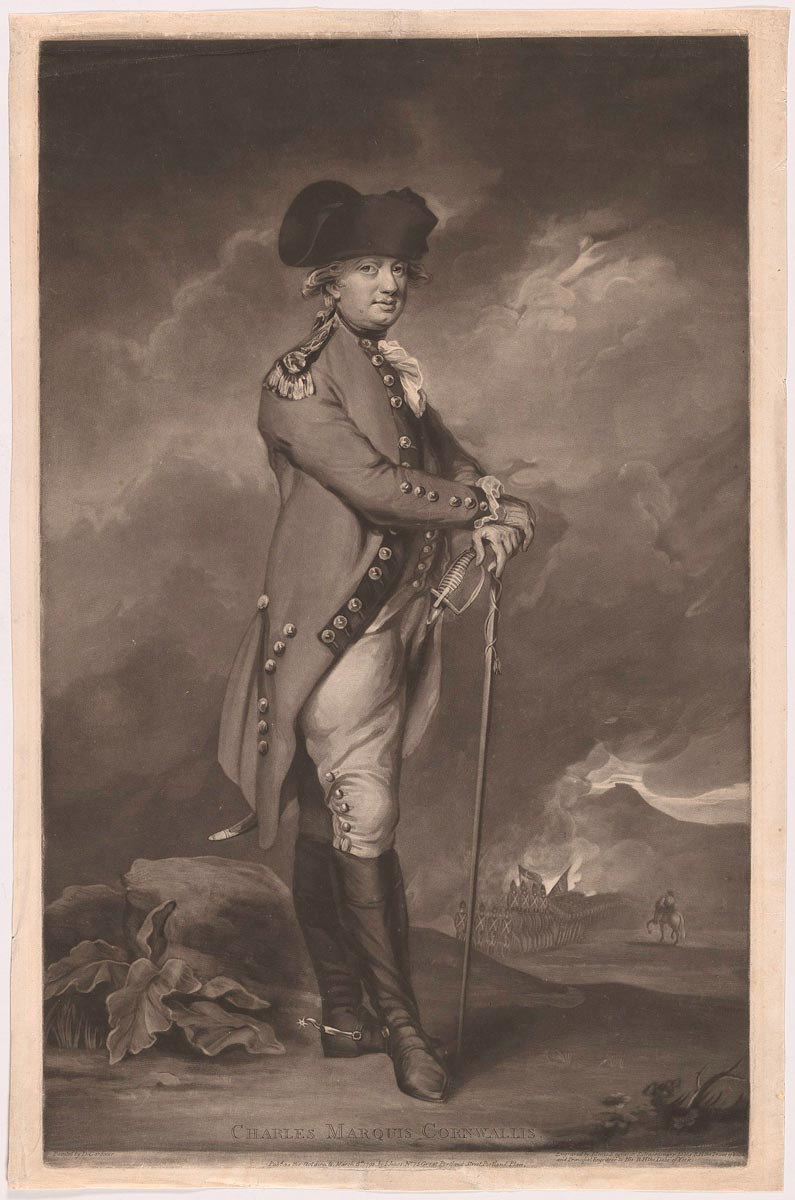

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess and 2nd Earl Cornwallis, was born in London on New Year’s Eve, 1738. Like many British aristocrats, Cornwallis came from a distinguished line of military officers and political elites. He was educated at prestigious institutions, including Eton College and Cambridge. However, in the 1750s, Cornwallis left his studies to pursue a military career.

Charles chose the army, while his younger brother William joined the Royal Navy. He participated in the Seven Years’ War in Germany. Cornwallis took part in the 1759 Battle of Minden on the staff of British general Lord Granby. He ultimately served with distinction in Germany for three years in the 12th Regiment of Foot.

Upon his father’s death in 1762, Charles replaced him as Earl and took his seat in the House of Lords. Cornwallis married Jemima Tullekin Jones in 1768. According to historian Richard Middleton, the marriage was unusual for the era as Jemima did not come from a socially prominent family. The couple have two children.

In 1770, Cornwallis received the prestigious Constable of the Tower of London position. He held this post for most of the remainder of his life.

Cornwallis Arrives in America

Like the future commander of British troops in North America, Sir William Howe, Cornwallis initially sympathized with the American colonists in their disputes with Parliament. In fact, as Richard Middleton notes (2022), Cornwallis was one of only five members of the House of Lords to vote in favor of the Stamp Act’s repeal.

Nevertheless, once war broke out in the spring of 1775, Cornwallis enthusiastically volunteered to go to America and suppress the rebellion. As a major general, he departed with British troops from Ireland in February 1776.

Cornwallis’s first assignment in America was to reinforce a British invasion of Charleston, South Carolina. The campaign was a disaster for the British, led by Sir Henry Clinton and Admiral Sir Peter Parker. After being defeated at Sullivan’s Island, Cornwallis and the remaining British forces departed to assist Sir William Howe’s invasion of New York.

The Battles of Trenton and Princeton

The British, under Sir William Howe, swept aside George Washington’s Continental Army across the New York City area between August and November 1776. By this point, Washington’s force was in full retreat across New Jersey. Moreover, the Continental Army was dwindling by the day, and many soldiers would soon go home on expiring enlistment contracts.

Howe was in no rush to pursue Washington as the weather worsened and preferred to enjoy the comforts of New York City. However, he left some British troops in New Jersey under Cornwallis to pursue Washington.

An American victory over unsuspecting Hessians at Trenton on December 26 stunned British leadership. Cornwallis moved to corner Washington’s army around Trenton. He thought he had done that in the second Battle of Trenton or Assunpink Creek on January 2, 1777. As the daylight faded, Cornwallis withdrew his forces to finish off Washington’s army the following morning. However, as historian Rick Atkinson points out (2019), Washington skillfully evaded Cornwallis’s troops. Moreover, Washington followed up the victory at Trenton with a rout of part of Cornwallis’s British force at Princeton on January 3.

Cornwallis’s failure to defeat Washington in January 1777 was the source of deep personal embarrassment. Moreover, Richard Middleton points out that Cornwallis would later tell George Washington that his actions in January 1777 were more impressive than the victory at Yorktown in 1781.

Capturing Philadelphia

British forces sought to recover from the shock of Trenton and Princeton by striking at Philadelphia. Middleton notes that Howe angered the more senior officer, Sir Henry Clinton, by promoting Cornwallis as second in command during the British campaign to seize the Patriot capital, Philadelphia.

Cornwallis’s troops performed well at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777. On September 26, Howe ordered Cornwallis’s troops to be the first to march into Philadelphia triumphantly.

Britain’s war for America began to change course in 1778. For starters, Sir Henry Clinton replaced Sir William Howe as the commander of British forces in North America. France also entered the conflict to support American independence in May of 1778. Spain and the Netherlands would later join the war against Britain.

As the war shifted, Cornwallis returned to Britain to tend to his dying wife. He was devastated by Jemima’s death in early 1779. However, Middleton notes Cornwallis returned to fight in America to escape the grief of his wife’s death. Although he admitted there would be “little glory,” Cornwallis’s return saw the general placed at the center of the American Revolution’s decisive chapter in the South.

The Southern Campaign

Now more concerned with fighting their traditional European foes like France and Spain, British officials shifted their sights away from the northern colonies towards the American South. Believing port cities like Charleston, South Carolina, would benefit the war effort against France in the West Indies, Clinton prepared a British invasion force. In addition to seizing Charleston, British officials believed the arrival of a major British army in the South would result in a massive influx of Loyalist volunteers.

After seizing Charleston in May 1780, Clinton left Cornwallis in overall command of British forces in South Carolina. As historian J. David Dameron (2003) points out, Cornwallis quickly secured the interior or backcountry of South Carolina with the help of British and Loyalist forces under Banastre Tarleton and Patrick Ferguson.

Cornwallis crushed the Continental Army of the southern department under Horatio Gates at the Battle of Camden in August 1780. However, British momentum stalled after the Patriot victory over Patrick Ferguson’s Loyalist troops at the Battle of King’s Mountain.

Moreover, the Continental Army’s southern department received a new capable commander in Major General Nathanael Greene. Greene skillfully rebuilt Patriot forces in the South. Although defeated at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse in March 1781, Greene had kept his army from being destroyed by Cornwallis’s troops.

According to Dameron, Guilford Courthouse revealed Cornwallis’s error in campaigning against Greene’s troops. Greene had led Cornwallis on a rambling pursuit across the Carolinas without risking a decisive defeat. Pursuing Greene through rugged terrain and poor weather took a heavy toll on British forces.

Surrender at Yorktown

Cornwallis’s inconclusive pursuit of Greene’s army ultimately led his weary army into Virginia. The British army in Virginia became trapped on the Yorktown peninsula by a Franco-American force under George Washington and the Comte de Rochambeau. Clinton had unwisely ordered Cornwallis to construct a base there instead of being recalled to the safety of British-controlled New York City.

After a three-week siege, Cornwallis sought terms from Washington and Rochambeau on October 17. Two days later, British forces formally surrendered on October 19, 1781. Cornwallis was not present at the ceremony. Instead, his second in command, Brigadier General Charles O’Hara, oversaw the British surrender. Washington insisted that O’Hara surrender to Benjamin Lincoln, who had been forced to surrender Charleston the previous year through unduly harsh terms.

One of the most enduring myths of the American Revolution is that Cornwallis refused to participate in the Yorktown surrender ceremony and meet George Washington. At times, the myth states that Cornwallis was too ashamed to have surrendered to take part in the ceremony. Other stories say that Cornwallis angrily refused to surrender his sword to George Washington as he saw the American commander as an inferior officer.

However, as Richard Middleton notes, these stories are equally untrue. In fact, Cornwallis suffered from a recurring bout of malaria at the time. Middleton says that once he felt better, Cornwallis attended a dinner held by George Washington several days after the British surrender.

As a prisoner of war, Cornwallis was exchanged for Henry Laurens, a former president of the Continental Congress.

The Blame Game: British Commanders in the American Revolution

During the American Revolution, the British army in North America endured a revolving door of senior commanders. British officials in London and public opinion tended to blame generals for Britain’s failures to crush the American rebellion.

As Rick Atkinson points out, Thomas Gage had been the first senior commander to face such scrutiny from the onset of the American Revolution in 1775. Despite conquering New York City and Philadelphia, Sir William Howe faced heavy criticism for failing to crush Washington’s army. Moreover, Sir John Burgoyne’s surrender at Saratoga in October 1777 made him the subject of much controversy in Britain.

Unlike most senior British commanders in the American Revolution, Cornwallis escaped much official criticism or public blame. Indeed, the blame for Yorktown largely fell upon the shoulders of Sir Henry Clinton. According to Chaim Rosenberg, while many British generals spent years writing memoirs blaming others for defeat in America, Cornwallis continued to serve in prestigious imperial positions.

Governor-General of India

Cornwallis served as Governor-General of the British East India Company (BEIC) between 1786 and 1793. According to Middleton, Cornwallis’s task in India was to restore the East India Company’s finances and improve its image after several scandals. Art historian Jennifer Howes (2023) explains Cornwallis’s service in India was celebrated with portraits and statues.

In a military capacity, Cornwallis temporarily weakened the power of the anti-British ruler of Mysore, Tippu Sultan, in the Third Mysore War. However, as Chaim Rosenberg points out, Cornwallis’s enduring achievement in India was the Cornwallis Code. This administrative reform prevented civil servants from engaging in private business, thus helping to reduce corruption.

Moreover, King George III rewarded Cornwallis’s accomplishments in India with the title of First Marquess Cornwallis in 1792. According to Rosenberg, Cornwallis longed to return to service in India following his departure for England in 1793.

Final Years

Cornwallis later served as Viceroy of Ireland. He won the respect of Protestant and Roman Catholic communities in Ireland. Cornwallis worked for Ireland’s parliamentary union with Britain, which would pass in 1800.

As commander of British troops in Ireland, Cornwallis suppressed an Irish rebellion and defeated a French invasion in 1798. Rosenberg notes Cornwallis wisely resisted collective punishment against Irish communities. Nevertheless, in 1799, he did narrowly survive an assassination attempt.

According to Middleton, Cornwallis urged the British government to grant political rights to Irish Catholics. Cornwallis resigned in 1801 after King George III refused to make concessions in favor of Irish Catholics.

Historian Alexander Mikaberidze (2020) notes that Cornwallis became the leading British diplomat in the Peace of Amiens. This short-lived peace agreement signed in 1802 between Britain and revolutionary France ended the French Revolutionary Wars. However, by 1803, Britain and France were again at war in the early stages of the Napoleonic Wars.

Cornwallis did get his wish to return to India in 1805. However, he fell ill and died shortly after his arrival.

Cornwallis had been a popular commander among his troops. Indeed, as Middleton points out, Cornwallis endeared himself to the soldiers by sharing many of their hardships while on campaign. He quickly recovered his reputation to serve British empire-building for the remainder of his life.

References and Further Reading

Atkinson, R. (2019). The British Are Coming: The War for America, Lexington to Princeton, 1775-1777. Holt.

Dameron, J. D. (2003). King’s Mountain: The Defeat of the Loyalists, October 7, 1780. Da Capo Press.

Howes, J. (2023). The Art of a Corporation: The East India Company as Patron and Collector, 1600-1860. Taylor & Francis.

Middleton, R. (2022). Cornwallis: Soldier and Statesman in a Revolutionary World. Yale University Press.

Mikaberidze, A. (2020). The Napoleonic Wars: A Global History. Oxford University Press.

Rosenberg, C. (2017). Losing America, Conquering India: Lord Cornwallis and the Remaking of the British Empire. McFarland.