Death and its inevitability have been a constant in humankind’s approach to living. In today’s world, we are perhaps not as vividly prompted to be conscious of our mortality as were the ancient Greeks, Romans, and early Christians. Artworks depicting skulls, hourglasses, dancing skeletons, and all manner of deathly imagery provided people with a vivid reminder, in the form of memento mori and memento vivere pieces, that death was just around the corner.

Memento Mori or Memento Vivere – A Case of Life and Death

In the early 1st century CE, the Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca wrote extensively about the need to live life with the awareness that death could arrive at any time. Marcus Aurelius furthered Stoic philosophy in the 2nd century CE. The Stoics promoted a logos, or discourse, that was the forerunner of what, in the 21st century, we might call mindfulness. They advocated living a life in harmony with nature, with thought and care, and crucially to our topic, an understanding that death is inevitable.

Marcus Aurelius, in his Meditations, wrote. “Let each thing you would do, say, or intend, be like that of a dying person.” This approach to life and death gave rise, in centuries to come, to schools of thought such as Zen Buddhism and Existentialism, both of which encouraged a conscious awareness of how life should be lived and death encountered.

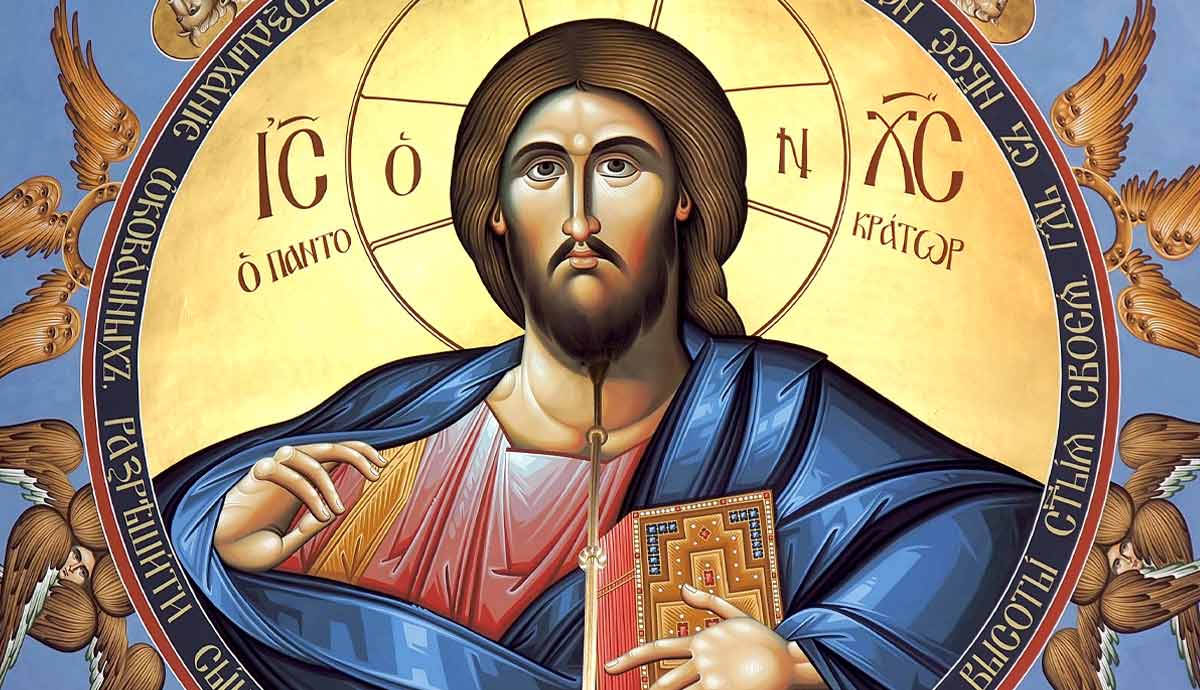

Christianity adopted similar ideals. In the Bible, in Genesis 3:19, we find the words, “Remember you are dust, and to dust you shall return.” Whilst such philosophies and concepts were second nature to the great thinkers of Ancient Rome and Athens, the general populace rarely had the advantage of education that might enable them to comprehend such depth of thought. It is perhaps this gap in literacy that gave birth to the ideas of memento mori and memento vivere in art. If one could not read the Bible or the works of Stoic philosophers, art explained them visually.

Perhaps less common in art history is the concept of memento vivere, meaning remember to live, although many memento mori works can be viewed from a memento vivere angle. While pondering the concept of unavoidable death, one may be prompted to seize life and live every moment to the fullest. The danse macabre was an outlandish example of the idea.

La Danse Macabre – Dancing With Death

Throughout Christianity’s development and dissemination, art and visual representations of passages from the Bible became a primary means of helping illiterate members of society, who were in the majority, to comprehend its teachings. When it came to emphasising the ephemerality of life and the certainty of death, the memento mori came into its own. A particular type, the danse macabre, provided an unambiguous illustration, as seen above, pressing home the warning that death was coming to all. Typically, the danse macabre was a seemingly jolly parade of skeletons interspersed with the living. They often have an air of celebration, although whether this is of life or death, we cannot be sure.

It has been suggested that danse macabre murals may have their origins in the period during and after the waves of the Bubonic Plague in the 14th century. They may have reminded people of the proximity of death, and in doing so, brought them closer to the church.

A Private Word – The Book of Hours

Whilst church wall-paintings were available to all and required no literary skills to aid understanding, the wealthy had their own, more personal, reminder of impending doom, the Book of Hours. Used as a devotional aid, Books of Hours ranged from simple books of psalms and prayers to illuminated manuscript examples such as Les Très Riches Heures du Duc du Berry.

Books of Hours were often decorated with pastoral scenes, including Bible tales as a visual prompt for prayer and contemplation. An indication of the ever-present harbinger of death in the Middle Ages, memento mori in the form of the skeleton was a popular theme.

Is This a Skull I See Before Me?

The visceral quality of Medieval memento mori imagery was understandably a product of its time. The aftermath of the Black Death, which decimated Europe in the 14th century, affected how people dealt with death. The dancing skeletons and those luring unsuspecting men to their doom were effective in ensuring that mortality was never far from anyone’s mind.

Funerary monuments and tombs were the obvious location for memento mori. From the Medieval period onwards, transi, or cadaver monuments, became a popular way for the powerful and wealthy to remind visitors to their tombs of the fleeting nature of life. It can be assumed that the incumbents of these often monumental and intricate creations intended, despite the costly designs they commissioned, to show their humility in the face of death. Examples exist of two-layered tombs with stone effigies of the deceased lying, hands in a position of prayer, and dressed in their earthly robes. Beneath them lies a skeleton, decaying, often riddled with worms, the memento mori.

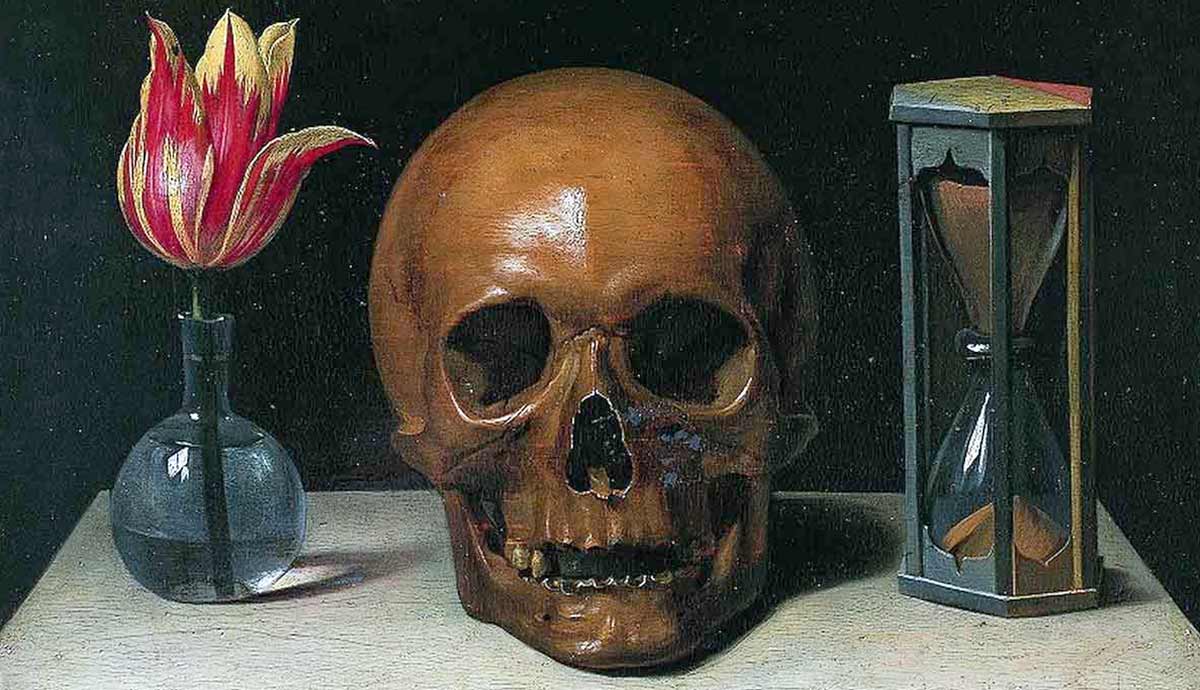

By the 17th century, painters in Leiden in the Netherlands and then further afield, a more allegorical approach to what Seneca referred to as preparing “our minds as if we had come to the very end of our life” had developed. Vanitas art, a variation of memento mori, offered a dramatic and sumptuous reminder of mortality. This was something that could be hung on a drawing room wall. Whereas the memento mori served as a moral warning that death is always near, vanitas paintings cautioned against coveting ephemeral luxuries that would disappear or degrade before your eyes.

The Fragility of Worldly Goods

In van Oosterwijk’s work above, several popular allegorical objects are included to raise the painting from a simple still life to a vanitas work. The ubiquitous skull is present, although it is not front and centre, grabbing the viewer’s attention as in Medieval art. Around it, we see the hourglass, the traditional depiction of time slipping away, flowers beginning to wilt, the cob of corn being nibbled away. Hidden within the opulent arrangement and jewel colors is a familiar reminder that death comes to everyone and everything. However luxurious and sought-after, nothing lasts forever.

Remember to Live – Memento Vivere

Perhaps it is a reflection on the proximity of death, ever a threat in a world of primitive medicine, that the opposite concept of memento mori, memento vivere, did not garner the same popularity in art as its deathly cousin. Memento vivere artworks, whether they be paintings or sculptures, are rare. Perhaps, though, it’s a matter of perspective. When we look at a Dutch Golden Age memento mori painting, replete with billowing blooms, golden timepieces, and delectable foods, rather than seeing the decay and impermanence of the earthly delights before us, we should remember to enjoy them whilst they last.

Memento Mori but Don’t Forget, Memento Vivere

There is a story that relates to the phrase’ memento mori’ that illustrates it perfectly. In the aftermath of important military victories, Roman generals were feted with a joyous procession. Idolized and celebrated, they were carried in a chariot through the streets of Rome. Also riding in the same chariot was a slave, standing just behind the eminent soldier. The role of this humble man was to repeat the words Respice post te. Hominem te esse memento. Memento mori into the general’s ear. The slave reminded the general to look behind him, that he was just a man and that he, too, would die.

Memento mori and its lesser-known partner, memento vivere, have a long history for good reason. It began with the Stoic philosophers formulating a code for living a good life and progressed to the vanitas paintings of the Dutch Golden Age, simultaneously warning us that everything ends and decays, but to remember to enjoy it while it lasts. The ideas still hold strong, and contemporary artists continue to apply the concept to their work. The recognition of death’s certainty is part of the human condition. Cultures across the globe celebrate life by looking death right in the eye. The Mexican Día de los Muertos is a prime example of this. Not only are ancestors honored, but the living are reminded that death is a part of the cycle of existence. We live, and therefore, we must die.