When we think of ancient temples, we generally imagine the Parthenon in Athens or the Pantheon in Rome: monumental structures dedicated to powerful gods where priests performed rituals to appease them. Yet in ancient Mesopotamia, at the onset of urban civilization starting in the 4th millennium BCE, temples were more than just religious centers. They were social institutions that facilitated trade, provided employment and education, and governed the city.

Urbanization & the Rise of Mesopotamian Temples

Ancient Mesopotamia, the “land between rivers,” was situated between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in what is today Iraq. It was in an area of fertile land that also encompassed the Levant and southern Anatolia, called the Fertile Crescent. In Mesopotamia, flat plains were irrigated to produce abundant cereals and date trees. The steppes allowed for animal husbandry and hunting. There were marshes with fish, fowl, and water buffalo. This wide variety of food sources allowed people to specialize in particular skills.

A by-product of labor specialization was that family units were no longer self-subsistent, requiring cooperation with others and a system of exchange to survive. This gave rise to the first cities, central locations where people could gather to exchange goods. While a large portion of city dwellers still subsisted via agriculture, a small portion of the population began to specialize in non-agricultural crafts, such as pottery and weaving. This development led to the need for an authority to organize a system of exchange for goods and services. This authority was the temple.

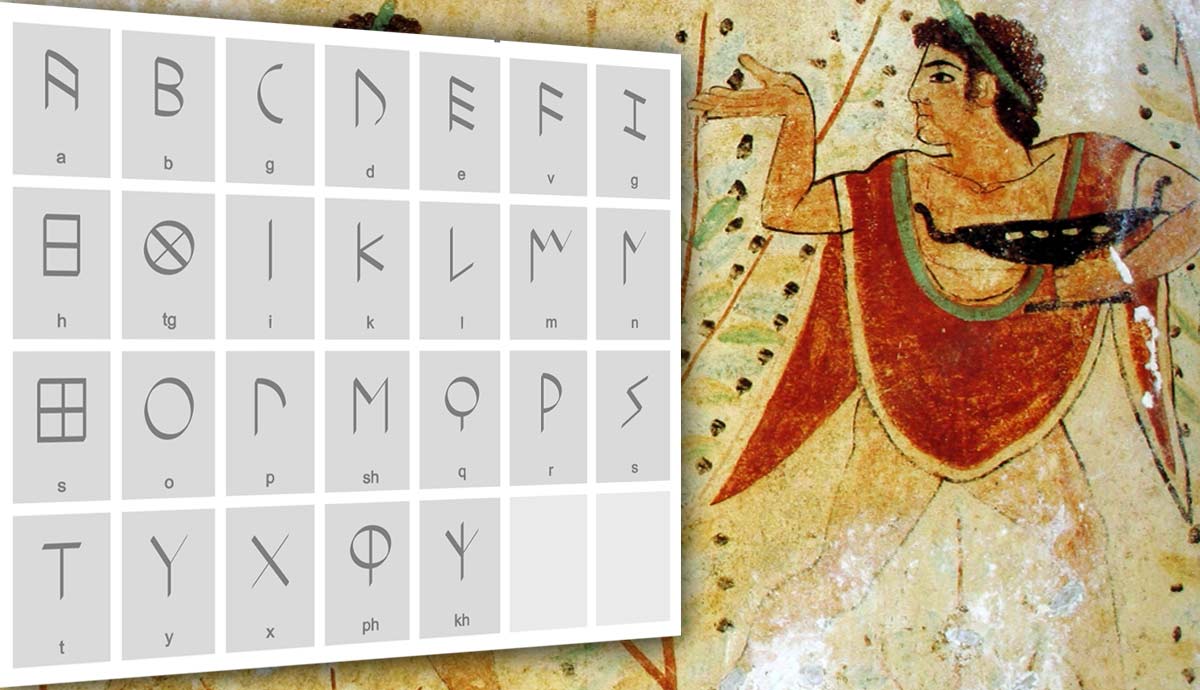

Religious figures were already highly regarded in society and were naturally trusted to administer on the people’s behalf, with a portion of production being paid for those services. This made the temple the central institution of early cities, and an increasing portion of the urban population found itself employed by temples and dependent on them for survival. Dependent laborers were given rations of food, cloth, and oil for their services. This kind of administration required organization and accurate record-keeping. Standard measures were created for land, goods, and time, and a new technology was invented to keep track of everything: writing.

Imposing Structures

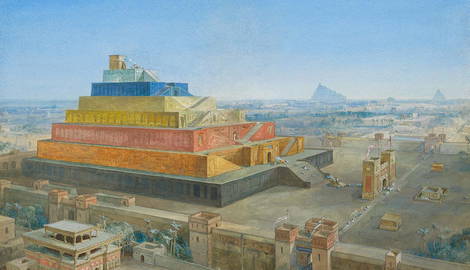

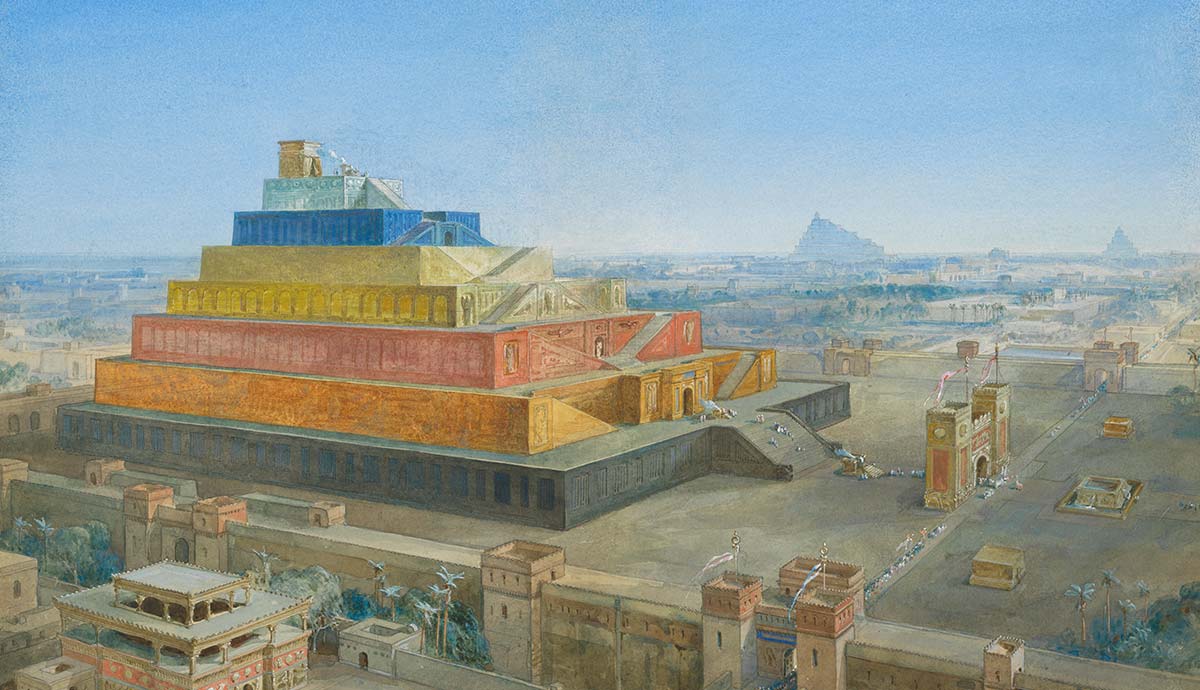

Given their central importance, temples were built on a grand scale to reflect that importance. It was tradition to rebuild temples on the exact site of the previous one, and after centuries, the debris from older temples built up in a mound, called a tell. Atop the tell, the temple presented a visual focal point. Uruk, generally considered to be the first city in world history, was surrounded by flat plains devoid of any mountains or bluffs, so the view of the city’s buildings and the temple that rose above the walls must have made for an impressive sight.

In southern Mesopotamia, where cities generally developed organically, the temple was centrally located, with the rest of the city growing outward from the temple precinct. In redesigned cities with planned layouts, such as Babylon and Borsippa, the city center was dominated by the religious sector, and the main processions from each of the city’s monumental gates led directly to it.

As cities became wealthier, temples grew into massive structures with decorated statuary and mosaics. These structures, called ziggurats, were made up of stepped platforms that rose in the center with a central staircase and two perpendicular staircases that climbed the face of the monument. The temple itself was located at the top and only accessible to temple priests. However, not all temples were located at the top of ziggurats. Some had just a vestibule where priests could go to entreat their gods.

Educational Centers

Temples were also where children, those of noble families or taken in by the temple, were educated in multiple disciplines. Known as edubbas, or tablet houses, the schools specialized in training scribes. The curriculum includes writing, math, astronomy, legal training, and administration skills necessary for the functioning of the city. Education was stratified, with the sons of nobles receiving advanced learning in literacy and religious texts, while the sons of lower-born families learning skills relevant to their family’s occupation.

The temple schools were attached to the temple building, reflecting the close relationship between education and religion. Children were enrolled as young as eight years old, and their education took approximately 12 years. Only a small percentage of the population became literate, and literacy was a source of prestige and authority. Education thus reinforced social stratification.

Reinforcing Social Stratification

Before the development of cities, social units were based on kinship ties, called households. These were extended family units that lived together, with each member fulfilling a specific role necessary for survival. For example, one member of the family might focus on weaving textiles while another would focus on agriculture. Whatever one member could not produce was supplied by another member. As households began to specialize in specific areas of production, they began to rely on other households to supply them with what they did not produce themselves. With the development of cities, rural family units moved to the urban area and could no longer depend on their traditional household ties. Instead, they depended on the temple.

The temple institution was structured as a household with the god as the “head” and those employed there or using its services as its dependents. In this way, the urban community was a larger scale version of a familiar social system. All those dependent upon the temple household provided a portion of their production or expertise to the institution in exchange for rations. However, how much someone received was dependent on their occupation. Unskilled laborers were at the bottom of the social hierarchy, with women receiving half as much as men. Supervisors received more, and skilled craftsmen received more than unskilled laborers. Those at the top of the social hierarchy were the scribes and leaders of the temple, the ones with the knowledge and skills to administer the city.

Religious Centers

Temple layouts were larger versions of the homes in which the Mesopotamians lived. There was no difference in kind, only in scale. There were bedchambers, kitchens, storage spaces, and communal areas. This is because the gods were, like in Greek mythology, anthropomorphized and seen as having the same needs as their human worshipers. The Sumerian word bitu, meaning “house,” was used to refer to temples. The building itself was sometimes deified and spoken of in texts as if it were alive and divine. In this sense, it was as though the god continued to live in the divine realm even when they were on earth.

All religious activity, such as sacrifices and rituals, happened within the temples, which were always located in a city. There is currently no evidence of any cult activity that took place outside cities. No natural features like mountains or trees were venerated. This could be due to the relatively featureless plains of southern Mesopotamia.

Since temples were primarily economic and administrative institutions, religion was what formalized and legitimized their broader activities. Temples and their priesthoods acted as intermediaries between the inhabitants of the cities and their gods. When a temple or the city was destroyed, it was seen as the god abandoning the city.

Political Hubs

Given their central importance to the community, the temple institution was politically dominant in early Mesopotamian history. As of the mid-3rd millennium BCE, the institution was incorporated into the palace hierarchy. As competition with other cities grew, the political authority of the temples was gradually usurped by a secular and military authority, namely kings. Conflicts with other cities were often framed as the military leader defending the land of the city’s patron god, giving the king an ideological basis for his leadership. Eventually, the distinction between temple leadership and palace leadership was erased when King Uru’inimgina took possession of all temple domains for himself through a series of reforms. While his reforms did not last long, later kings always held the position of high-priest of the temple institution.

Most Mesopotamian kings undertook temple-building projects to legitimize their rule. Since kingship was seen as having descended from the gods, the act of building a temple showed the people the king’s divine favor. Often, construction was justified as being requested directly by the gods. Kings would also place their family members into prominent temple positions. For example Sargon, the king of Akkad, installed his daughter, Enheduanna, as high priestess of the moon god Nanna at Ur. She wrote a series of hymns to various gods, integrating the disparate cults into a singular religious system. She is also the first identifiable author in world history. For the next few centuries, any ruler who claimed authority in Ur would install their daughter as high priestess of Nanna.

Temples in ancient Mesopotamia were more than just places of worship. They were economic hubs, political authorities, and education centers. They formed the beating heart of the city. Empowered by a shared religious ideology, temples structured urban life and facilitated the development of the world’s first cities.

Select Bibliography

Hundley, Michael B. (2013). Gods in Dwellings: Temples and Divine Presence in the Ancient Near East. Society of Biblical Literature.

Makkay, J. (1983). The Origins of the “Temple-Economy” as Seen in the Light of Prehistoric Evidence. Iraq, 45(1), 1–6.

Nadali, D. & Polcaro, A. (2016). The Sky from the High Terrace: Stuy on the Orientation of the Ziqqurat in Ancient Mesopotamia. Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, 16(4), 103-108.

Pongratz-Leisten, B. (2021). The Animated Temple and Its Agency in the Urban Life of the City in Ancient Mesopotamia. Religions, 12(8), 638.

Ur, J. (2014). Households and the Emergence of Cities in Ancient Mesopotamia. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 24(2), 249–268.

Van De Mieroop, M. (1997). The Ancient Mesopotamian City. Oxford University Press.

Yıldırım, E. (2017). The Power Struggle Between Government Officials and Clergymen in Ancient History. Journal of Ancient History and Archaeology, 4(3).