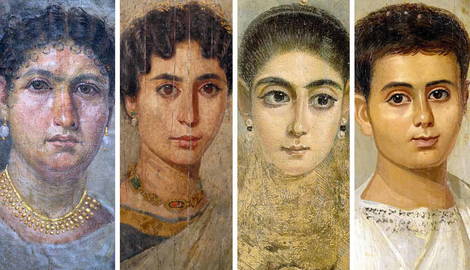

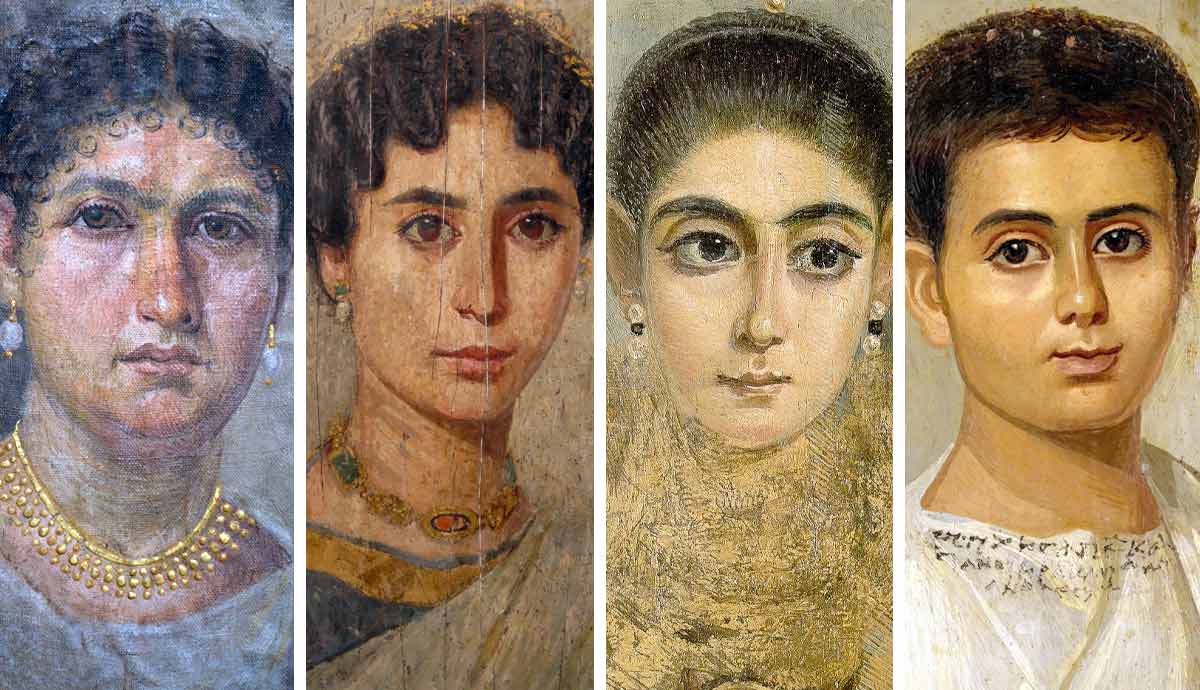

The Fayum portraits are realistic paintings of deceased individuals that were placed over their mummies during the first three centuries of the Common Era in Egypt. These were portraits of the elites who wished to reach the afterlife retaining their lifelike appearance. The region of Faiyum Oasis, where most of these portraits were found, had a diverse community of affluent immigrants, so cultural and religious traditions mixed and evolved together. Read on to get familiar with six striking examples of Fayum portraits.

1. Portrait of the Boy Eutyches: The Mysterious Fayum Portrait

Fayum portraits were remarkable examples of Egyptian funerary art that were mostly produced between the 1st and 3rd centuries CE. The name Fayum came from the Faiyum Oasis, where the majority of known portraits were found. Although Faiyum was not the only place where such portraits were created, the majority of them were discovered in that area. Today, art historians have found over 1,000 such portraits. At the time of their creation, Egypt was part of the Roman Empire. Thus, the portraits blended Egyptian burial tradition with Roman and Greek schools of painting.

There is no information left about those who were buried with these portraits or those who created them. For that reason, the portraits usually have vague, generalized titles or numbers that are used by archaeologists and experts. There are, however, rare exceptions, such as the famous portrait of a young boy. The backside of the portrait had an inscription in Greek that stated that the boy was named Eutyches and that he was a former slave who was freed. There is no extra information that could possibly explain how an ex-slave managed to become so prominent at his young age to deserve a funeral with a portrait. Another interesting detail is the thin purple stripe on his tunic. Purple was an expensive color that marked the wearer’s status. Such stripes were usually worn by the cavalry officers who belonged to the upper classes. Some historians note that some slave owners freed their slaves posthumously or right before death, but it still does not explain Eutyches’ dress.

2. Fayum Mummy Portrait of Herakleides

Fayum portraits were painted on boards or linens. The mummified body of the deceased was wrapped in cloth, and the portrait was placed in the area of their head. These portraits were then buried with mummies, as they were intended for the dead rather than the living. Most portraits showed young and beautiful faces of people who would never reach old age; many of them were still children before their teens. Due to illnesses and life conditions, they rarely lived more than forty years. Infant mortality was high, with very few children reaching adolescence.

Like other Egyptian tombs, Fayum burials were often destroyed by vandals and looters looking for jewelry buried with the bodies. Portraits were either separated from the mummies even before the archaeologists arrived or divided later during the research. Today, museums aim to preserve the mummies as intact as possible and occasionally put on display entire mummies with portraits still attached. One of such famous artifacts is the mummy of Herakleides, preserved in the Getty Villa in Los Angeles. Herakleides was a young man in his early twenties and possibly was related to the classes of priests or scribes. The main indicator for that was a surprising discovery made during a CAT scan of the mummy: underneath the bandages, researchers found another mummy—that of an ibis, a small bird representing the god Thoth. As a deity, Thoth was responsible for knowledge, science, and solving legal disputes.

3. Tomb of Aline

Fayum portraits rarely included any indication of the deceased person’s identity or occupation. Thus, although the portraits were incredibly realistic and detailed, archaeologists could rarely say with certainty who exactly was buried in these portraits. One thing we know for sure: these were not ordinary graves but rather the burials of local elites. Mummification was a lengthy process that took over two months and required considerable skill and effort. The preserved body of the deceased was meant to serve them in the next life, with the portrait replacing their face.

Still, burial sites often tell stories. One of the most famous Fayum tombs was the Tomb of Aline, discovered in 1892. The tomb contained eight mummies, three of which had painted portraits. A Greek inscription stated that the oldest of them was the woman named Aline, the daughter of Herodes, who died aged 35 in the 10th year of her contemporary Roman Emperor’s reign. Other mummies in the tomb include three young girls and a grown-up man—possibly Aline’s daughters and husband. The man did not have a painted portrait but a gilded paper mask, which allowed for much less likeness with the deceased person. This, however, might mean there was no uniform burial tradition in his and his family’s lifetimes and that several forms of tomb decor could be practiced at once.

4. Funeral Shroud With Anubis and Osiris

As the Roman Empire conquered Egypt, traditions and beliefs mixed, just as artistic techniques and inspirations did. According to most historians, the Romans were rather indifferent to local religious practices, leaving them as they were. The region around Faiyum was popular among immigrants, particularly Greeks, Syrians, and Jews. Most of them were not workers but rich and established people who considered Fayum a comfortable and prestigious place to settle. Such ethnic diversity led to the formation of a multi-faceted and bright cultural landscape. Today, archaeologists still find work contracts in Egyptian writing on materials typical for Greeks. The art industry in the region was well-developed and functional: some sources mention that painters and sculptors had their professional unions and separated their specialties and zones of influence.

Among the most striking works that demonstrated the cultural and religious diversity of the region, as well as the incredible complexity of the funerary portraits, were those found in Saqqara. These were not small portraits but life-sized complex figure paintings, done with tempera (a mixture of egg and pigment) on linen shrouds. One of the remaining portraits featured a figure of the deceased dressed in white Greek clothing, greeted by the Egyptian god of funerary rites and the guide to the underworld, Anubis. On the other side of the figure was another god, Osiris, who was present in his mummy shape. The composition presents a striking mix of visual traditions: Anubis was painted in profile according to Egyptian tradition, Osiris was shown from the front, and the dead man stood with his weight on one foot—a pose known as contrapposto, from Greek sculptures.

5. The European Woman

One of the most remarkable features of the Fayum portraits was the incredible realism of the faces and eyes. Certainly, there was some degree of stylization; the eyes were visibly larger than they were supposed to be on a real human face, yet their faces still looked realistic. This effect became possible not only because of the unique skill of local artists but also due to the medium that was used. Fayum portraits were painted using a technique called encaustic painting.

The painters mixed colorful pigments with molten beeswax and applied it with a brush or a metal spatula. After applying all layers and areas of color, the painted surface was heated to bind the layers of wax together. Additionally, some artists would scrape or reshape the wax surface to give extra texture to the image. The technical skills and individual styles of each master varied and are still clearly visible to museum visitors. Unfortunately, we do not know any names of the artists behind these works. L’europeenne, or The European Woman, was one of the most remarkable yet mysterious examples of a Fayum portrait. Her appearance and dress suggested she came from the territory of present-day Italy and held a significant social status.

6. Fayum Portraits and Fashion: Portrait of a Woman

The Fayum portraits depicted the local elites who had time and money to care for their appearance and follow trends. Archaeologists often date these portraits by the hairstyles and jewelry depicted. Faiyum Oasis and its inhabitants lived separately from major cities, encapsulated in its own cultural landscape, so popular fashions were late for about a decade.

One of the most important features of the Fayum portraits of affluent women was jewelry, painted in detail and decorated with gold leaf. Shapes and inclusions indicated not only the social status of the wearer but also their ethnic and cultural affiliations. One of the most famous portraits from the collection of The British Museum represented a woman in an emerald and ruby necklace, pearl earrings, and gold wreath in her hair. Hairpins and bracelets were also popular types of jewelry. Archaeologists actually managed to uncover some of the artifacts and match them to their painted copies from the Fayum portraits. Paintings of children often featured amulet necklaces, supposed to ward off evil and illness.