Summary

- In 1922, Howard Carter discovered Tutankhamun’s tomb. In the following years, several members of the excavation team died, sparking rumors of a deadly “mummy’s curse.”

- The legend of the curse was fueled by newspapers in the 1920s, but modern evidence shows the story was a myth rather than reality.

In 1922, a team of excavators, led by Howard Carter, opened Tutankhamun’s tomb. Soon after, many of them were dead. Rumors of a curse began to spread. What really happened to Howard Carter’s team, and what is the source of the story of the mummy’s curse?

Discovering Tutankhamun

Howard Carter, born in London in 1874, began working in Egypt at the age of just 17. By 1907, he was employed by the 5th Earl of Carnarvon to lead excavation teams in the search for Ancient Egyptian treasures.

The working relationship between Carter and Carnarvon was a good one, but by early 1922, Carnarvon was growing increasingly disillusioned. Carter had been digging for 15 years, and he felt they had very little to show for it. Despite working in the Valley of the Kings, the burial place of New Kingdom pharaohs and nobles, Carter had yet to find anything for Carnarvon that was worthy of the headlines.

But it wasn’t necessarily Carter’s fault. The problem with treasure hunting in the Valley of the Kings was that everyone else had already had the same idea. Graverobbing had been happening for millennia, and previous modern excavations by other teams had already uncovered 62 tombs in the valley. So, when Carter kept returning from Egypt more-or-less empty handed, it seemed like there was nothing left to find.

Carnarvon considered withdrawing his funding, but Carter remained convinced that the Valley of the Kings had at least one more surprise in store. Throughout the valley, excavators had run into several references to a pharaoh called Tutankhamun, but as of 1922, no tomb bearing that name had been found.

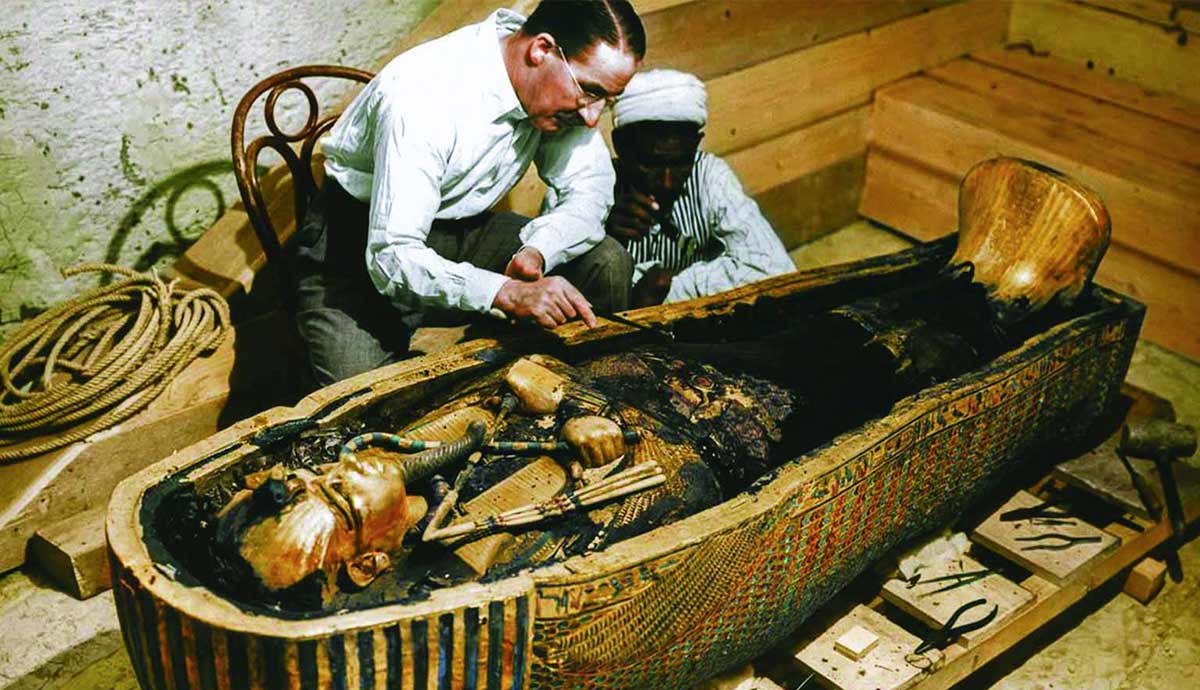

Carter persuaded Carnarvon to fund just one more season of excavation, hoping that this time, he would make a discovery that history would remember. Finally, on November 4th, 1922, Carter found what he had been looking for. Built into the valley floor, buried in the sand and covered by debris, was the elusive tomb of Tutankhamun.

Tutankhamun’s Tomb

“…As my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues, and gold – everywhere the glint of gold. For the moment – an eternity it must have seemed to the others standing by – I was struck dumb with amazement, and when Lord Carnarvon, unable to stand the suspense any longer, inquired anxiously, ‘Can you see anything?’ it was all I could do to get out the words, ‘Yes, wonderful things.’”

That is what Howard Carter said when he finally set eyes on the tomb he had spent years searching for. Such a reaction might make us think that Tutankhamun’s tomb was especially lavish, but this is not strictly true. In fact, it was smaller and less richly decorated than most other royal tombs of the time. Its extraordinary state of preservation gave it the illusion of opulence, and its compact size meant that Tutankhamun’s grave goods had to be crammed in like sardines.

This has led Egyptologists to conclude that Tutankhamun’s final resting place was not originally intended for him. Most Egyptian pharaohs commissioned their own tombs and had them built while they were still alive. There is even a history of pharaohs trying to outdo each other with increasingly large and luxurious tombs. The Pyramids of Giza, for example, which were built over a thousand years before Tutankhamun was born, were designed to reflect the wealth and power of the pharaohs interred within them.

But Tutankhamun was just 18 or 19 when he died, and although he had already ordered a tomb to be built for him, it was nowhere near finished upon his premature death. Instead, he could have been buried in a smaller tomb that had been originally intended for his advisor, Ky.

However, the most enduring legacy of Tutankhamun’s tomb is not its size or its grave goods, it is the deadly curse that is said to have struck down any who disturbed it.

The Mummy’s Curse

In April 1923, less than two months after the tomb’s inner Chamber was opened, Lord Carnarvon’s relatives were rushing to be at his side during his final moments. According to his doctor, Carnarvon had been bitten on the cheek by a mosquito and it had become badly infected. On April 5th, at the age of 56, he succumbed to blood poisoning.

Two weeks before Carnarvon’s untimely passing, a journalist, Marie Corelli, wrote a piece for New York World Magazine in which she asserted that “dire punishment” would find those who opened the Pharaoh’s tomb. Carnarvon’s death seemed to prove her right, and people started whispering about a “Mummy’s Curse.”

To add to the mystery, there were reports of a massive power cut across Cairo the night Carnarvon died, plunging the city into darkness as the Earl breathed his final shallow breath.

But that was nowhere near the end of it. A month later, George Jay Gould, an American railway executive who had visited Tutankhamun’s tomb, died of a fever he contracted in Egypt. Not long before this, Howard Carter had given his friend Bruce Ingham a gift from the tomb. It was a mummified hand wearing a bracelet that was said to be inscribed with the words: “Cursed be he who moves my body. To him shall come fire, water, and pestilence.” Shortly after receiving the macabre gift, Ingham’s house burned down. When he tried to rebuild, it was damaged in a flood.

In early 1924, Sir Archibald Douglas-Reid, a radiologist who x-rayed Tutankhamun’s mummy, traveled to Switzerland for a surgical procedure that was supposed to help treat the spread of skin cancer. He died on January 15th due to complications of the surgery.

Then, in 1929, Howard Carter’s secretary, Richard Bethel, was found dead in his bed at a club in Mayfair. At first, the reports said he had died of a heart attack, but further investigation revealed that he had been smothered. Bethel’s father followed his son to the grave a year later, throwing himself out of a seventh-floor window. He left a note that said, “I really cannot stand any more horrors and hardly see what good I am going to do here, so I am making my exit.”

But what of Carter himself? Surely, as the head of the excavation and the first person to gaze upon Tutankhamun’s tomb in thousands of years, he should have suffered the worst tragedy of all?

Carter lived until 1939, when he died of lymphoma at the age of 64. Lady Evelyn Herbert, Lord Carnarvon’s daughter, who was with her father and Howard Carter when they entered the tomb, also lived long after the excavation. She died in 1980 and suffered no known tragedy that could be attributed to the curse.

So, how did she and Carter manage to avoid Tutankhamun’s deadly wrath?

Evidence of Curses

Despite the prevalence of ancient Egyptian curses in 20th and 21st-century media, there isn’t that much evidence in the archaeological record. Some tomb curses exist, but mainly in private tombs from the Old Kingdom, thousands of years before Tutankhamun (1332-1323 BCE). These texts explicitly threaten harm to those who would desecrate the grave or steal from it.

The tomb of Khentika Ikhekhi from the 6th dynasty (2345-2181 BCE), for example, contains an inscription that reads:

“As for all men who shall enter this, my tomb, impure, there will be judgment. An end shall be made for him. I shall seize his neck like a bird. I shall cast the fear of myself into him.”

However, no curse was ever found inscribed in Tutankhamun’s tomb or any other New Kingdom royal tombs. So, if it wasn’t a curse that brought about the deaths of Lord Carnarvon and several others on the excavation team, what was it?

Since the opening of Tutankhamun’s tomb and the tragedies that followed it, many scholars, scientists, and enthusiastic amateurs have tried to find a logical explanation for the so-called curse.

One theory suggests that a toxic fungus could have been lurking within the sealed tomb, and that it was released when Carter’s team opened it. This theory became especially popular after the tomb of Casimir IV Jagiellon, a 15th-century CE Polish king, was opened for conservation work in 1973. Shortly afterwards, ten of the twelve people involved in the opening of the tomb were dead.

The media compared the premature deaths to those that followed the opening of Tutankhamun’s tomb, claiming that there was a “Jagiellonian curse.” But then a microbiologist identified the presence of a deadly fungus, Aspergillus flavus, in the tomb. It wasn’t a curse that killed the conservation team; it was the fungus.

But nothing like this was ever found in Tutankhamun’s tomb, and the deaths all had unrelated causes: blood poisoning, fever, cancer, pneumonia, suicide, and even a possible murder.

Of the 58 people who were present at the opening of the tomb, only eight died within the following twelve years, and many of them have reasonable explanations. Lord Carnarvon, for instance, had a history of poor health and regularly suffered from lung infections. With his weakened immune system, it is no surprise that an infected mosquito bite had such a deadly effect on him. Another of the fatalities, Sir Archibald Douglas-Reid, the radiologist who x-rayed Tutankhamun’s mummy, developed skin cancer as a result of exposure to radiation during his career.

The deaths that followed the excavation of Tutankhamun’s tomb were not, therefore, caused by an ancient curse or a toxic fungus, but by things that probably would have happened anyway. Would Carnarvon have been bitten by a mosquito if he hadn’t been in Egypt in 1922? Maybe not, but even if he hadn’t, one of his frequent lung infections probably would have finished him off sooner or later. Douglas-Reid had skin cancer before he even went near Tutankhamun’s mummy, and George Jay Gould contracted a fatal fever while in Egypt; a risk most travelers took in the days before widespread access to antibiotics and vaccines.

The only link between the people who died was that they had been somehow involved in the opening of the tomb of Tutankhamun. The tomb itself had nothing to do with their deaths, and nothing to do with any of the various misfortunes suffered by those who survived.

So, why does the legend of the Mummy’s Curse endure? In the 1920s, tales of curses brought in readers, which encouraged newspapers to publish more of them. The evidence tells us that Tutankhamun’s tomb was never cursed, but it did make for a good story, one that still captures the imagination over 100 years later.