In the mid-20th century, much of Latin America was ruled by wealthy autocrats or military regimes. These countries’ powerful northern neighbor, the United States, funneled economic and military support their way, turning a blind eye to human rights abuses and corruption so long as it meant communist forces were kept at bay. But the successful 1959 Cuban revolution sparked hope in the region—another way was possible, and opposition movements began popping up, promising a more egalitarian, prosperous future for all.

Autocracy and Imperialism: A Revolution Takes Shape

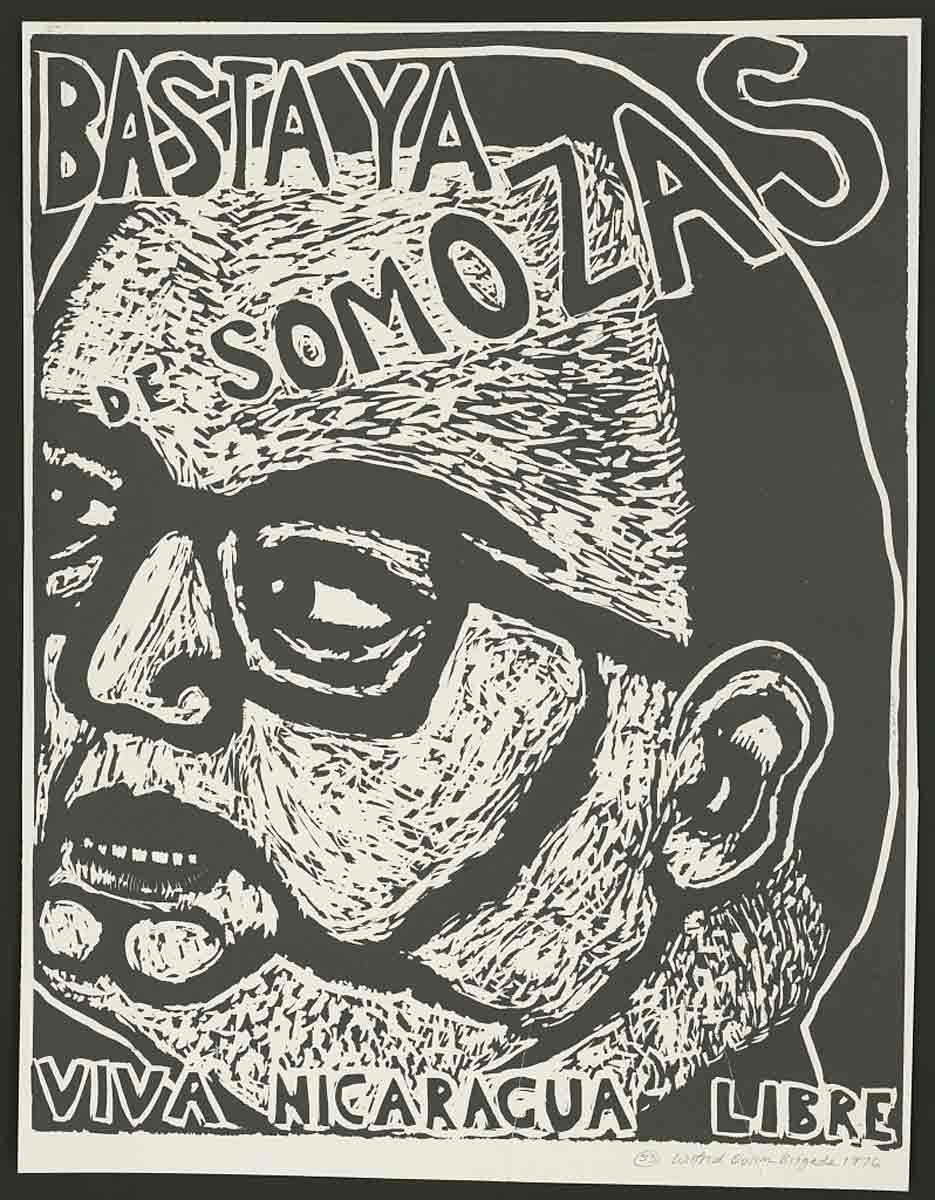

By the 1970s, when a viable opposition movement first began to take shape in Nicaragua, the country had been ruled by the Somoza family for decades: first, the father, Anastasio, who came to power in 1937, then his eldest son, Luis, and finally his younger son, also Anastasio. The family spent its time in power gobbling up the country’s land, granting political favors to the wealthy—including US businesses—and enriching themselves. The country also retained US support by providing a base from which the CIA could carry out operations in neighboring countries.

Throughout the family’s rule, a veneer of democracy was retained, with opposition parties allowed political space, but elections were rigged, and outright dissent was quickly quashed. It was no surprise when the revolutionary fervor that had begun to take root in the region with the success of the Cuban revolution made its way to Nicaragua as well, with initial pro-labor, anti-imperialism groups forming in the 1960s. The group that would come to take center stage, the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (Sandinista National Liberation Front, FSLN), was founded in 1961 by Carlos Fonseca, Silvio Mayorga, and Tomás Borge, three Nicaraguan exiles living in Honduras.

The FSLN would ultimately comprise three separate factions with the same goal—overthrowing the dictatorship in favor of socialist reforms—but differing ideas about how best to achieve it, with various tactics employed throughout the 1970s.

At War With the Somozas

After a 1972 earthquake destroyed much of Managua and international aid disappeared in the Somoza family’s pockets, the tide began to turn. The Somozas’ blatant theft of earthquake aid was too much, even for some of the country’s elites, who also faced new “emergency” taxes implemented for disaster aid and reconstruction. Though many Nicaraguans didn’t necessarily agree with the socialist or communist policies of the country’s revolutionary groups, a coalition movement slowly began to coalesce around their common ground: it was time for the Somozas to go. Strikes and demonstrations began in earnest while the FSLN sought recruits in the countryside.

One key moment in the fight came when the FSLN succeeded in holding a group of wealthy government officials hostage in 1974, presenting the Somoza government with a series of demands for their release. Once their demands were met and the hostages released, Somoza’s response was an indiscriminately violent crackdown designed to “root out” guerrillas that terrorized the rural population. The attacks horrified the Catholic Church, which brought worldwide attention to the atrocities of the Somoza regime.

International attention brought a brief reprieve, but violent “anti-terrorism” campaigns, martial law, and suspension of the free press continued on and off throughout the decade. The more the government cracked down on dissident groups and sympathizers—perhaps most notably Joaquín Chamorro, a popular newspaper editor Somoza had assassinated—the larger the opposition movement grew, while the National Guard’s human rights abuses drove the regime’s foreign allies to distance themselves.

The FSLN Comes to Power

By the end of the decade, the country’s National Guard could no longer counter the revolutionary army. The FSLN had solidified a broad base from nearly all sectors of Nicaraguan society and was receiving additional support from the USSR, Cuba, and other countries in Latin America. It controlled nearly the entire country, except for the capital, Managua, and had established a provisional government, the Junta de Gobierno de Reconstrucción Nacional (Government Junta for National Reconstruction).

Meanwhile, military repression combined with nationwide strikes and capital flight had devastated the economy and driven away foreign and military aid to the Somoza regime. In July 1979, FSLN guerrillas surrounded the capital, and the Somozas fled.

Nicaragua’s initial post-insurgency government was a coalition of FSLN leaders and other non-Sandinista opponents of Somoza, a measure designed to bolster the image of the new regime as democratic and assure the Nicaraguan people that the diverse interests of all were represented. The new government, not in a position to burn bridges, sought diplomatic relations with countries at all points on the political spectrum, including the US.

The FSLN had inherited a country in ruins: 50,000 people had been killed during the war, 600,000 were homeless, and the economy was devastated. Rebuilding it was a top priority, and, counter to the group’s Marxist ideological roots, private sector representatives were appointed to handle the essential economic tasks of renegotiating debt and securing aid.

Equally important, however, was retaining the group’s support base, the rural and urban poor who believed in the radical social transformation project the FSLN had promised. Leadership quickly moved to adopt some of the most prominent measures it had been advocating over the previous decade, including the nationalization of the land the Somozas had accumulated, which was distributed to farming cooperatives. Spending on health and education increased dramatically, vaccination campaigns were undertaken, health centers and schools were built, thousands of new teachers were trained, and the new government received an award from UNESCO for its literacy crusade.

Despite the inclusive nature of the new regime, in a relatively short time, it became apparent that the FSLN was truly in charge, with Sandinistas taking over the highest positions in leadership and holding the majority in representative organizations. As a result, some more moderate elements dropped out of the coalition. Without these moderate elements to act as guardrails, the FSLN government slowly adopted more radical measures that drew the condemnation of the country’s middle and upper classes as well as key foreign powers. Land and assets were confiscated from the wealthy and business leaders while the government sought closer ties with socialist countries, and democratic elections were deemphasized in favor of popular organizations providing feedback and input to the coalition government.

Counterrevolution: Opposing the Opposition

Backlash to the FSLN came almost immediately from the remaining Somoza supporters and elites, as well as the moderates who felt locked out of governing by the Sandinistas. Of greatest concern, however, was the counterrevolutionary army, the Contras, that quickly sprung up among former National Guard members—backed by a rich, powerful ally.

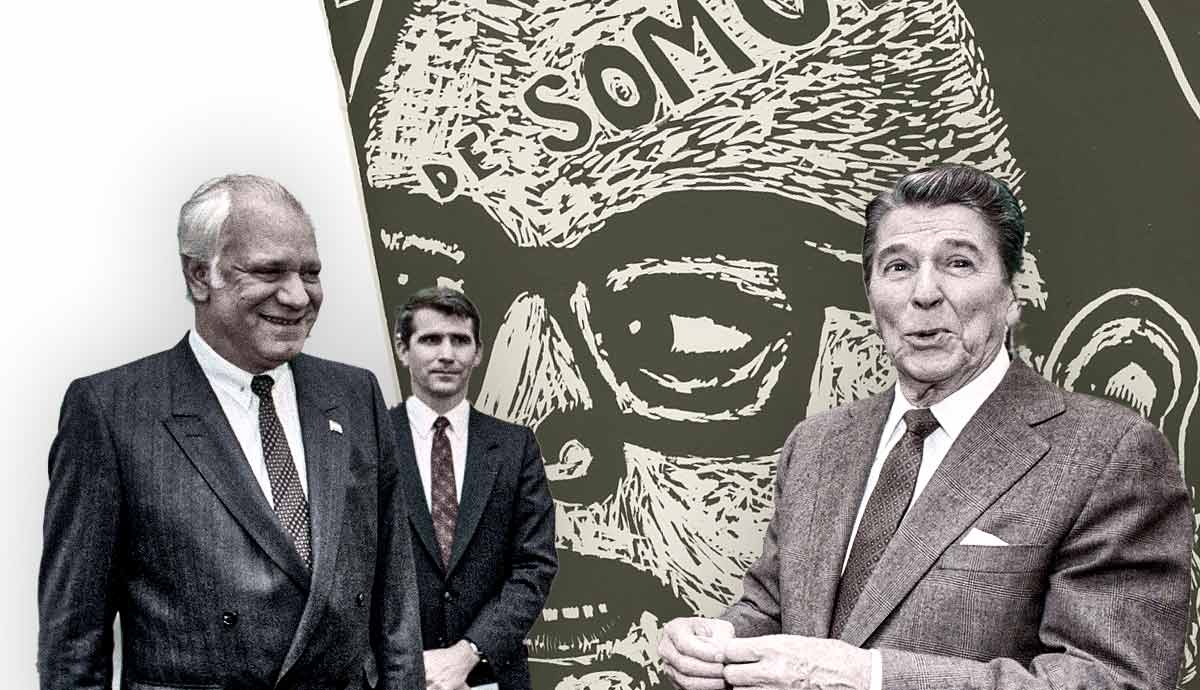

US President Jimmy Carter had withdrawn support from the repressive Somoza regime in the late 1970s, helping to solidify the FSLN’s victory. Once they took power, he worked to develop a relationship with the Sandinistas and sought Congressional approval for aid that he believed would help ensure the new regime did not turn further leftward in its fight for social justice but maintained a mixed economy and a cooperative relationship with the US. Carter’s time in office, though, was nearly at an end by the time the FSLN achieved victory.

After the US presidential elections in 1980, the Sandinistas quickly drew the ire of Carter’s successor, Ronald Reagan, by reportedly aiding revolutionaries in El Salvador, and US aid to Nicaragua was quickly terminated. Within his first year, Reagan had determined that the Sandinistas were also displaying “unacceptable” Marxist and totalitarian tendencies, and he became determined to remove them from power.

An outright war was out of the question, so instead, Reagan opted for a “low-intensity” conflict—comprising military, economic, political, and psychological pressures—designed to undermine the government and its popular social reform projects. Primary among these was his decision to finance, arm, and train the emerging Contra army.

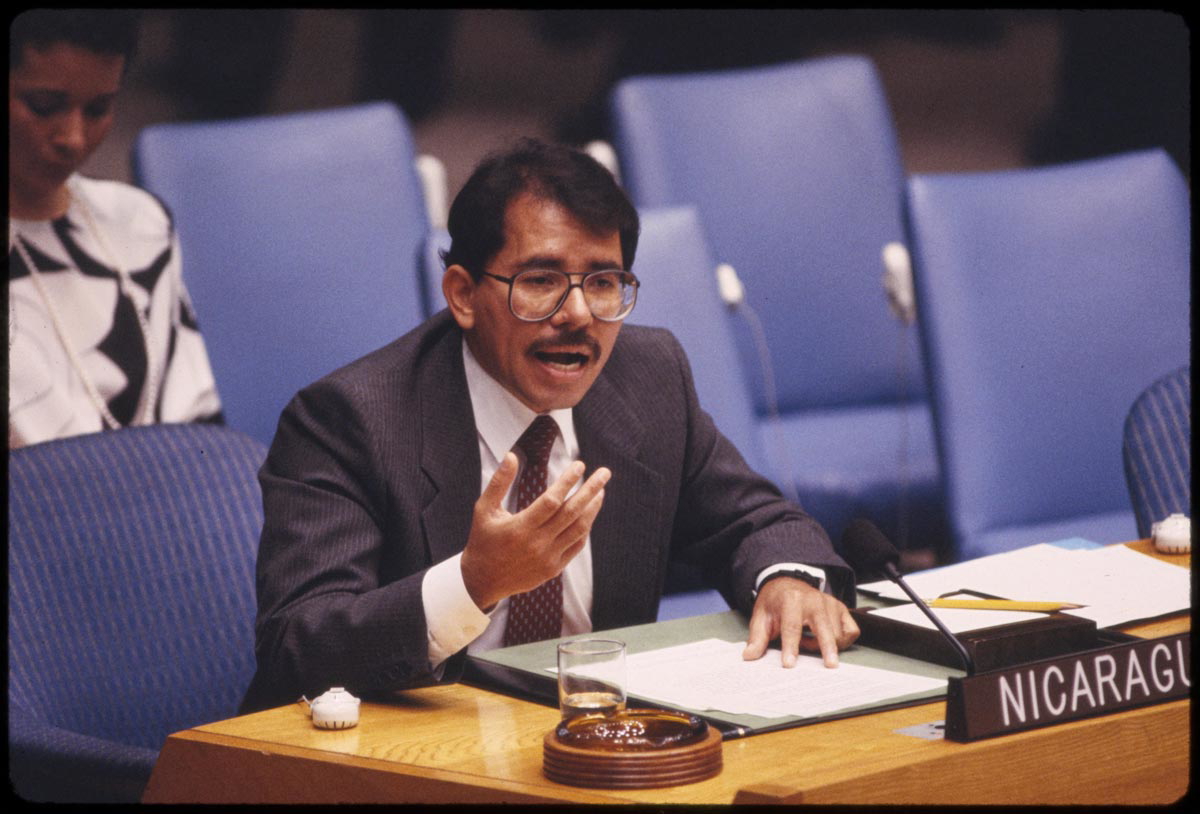

Having apparently made an enemy of the new US administration, Nicaragua held presidential and parliamentary elections in 1984 with the hope of gaining support among democratic governments. Though boycotted by right-wing parties and condemned as rigged before they even happened by the US, Nicaraguans turned out in droves to vote, and the FSLN candidate, Daniel Ortega, a prominent figure in the revolutionary movement and existing governing coalition, won handily. The FSLN also held a majority in the National Assembly, ensuring their economic and social reform projects could continue.

The elections did little to legitimize the government outside the country, and the war with the Contras deepened. As the Contras launched more and deadlier attacks around the country, the Sandinistas were forced to dedicate increased spending to defense rather than the social justice and poverty reduction programs it had made the hallmark of its victory. Meanwhile, thanks to a US embargo, it was simultaneously relying more heavily on trade and financing from Cuba and the Soviet Union, the very countries the US wanted to stop the new regime from emulating. As opposition grew, the Sandinistas’ regime looked increasingly like its predecessor’s, rescinding press freedoms and cracking down on opposition organizations.

The Revolution Comes to an End

Early on, the FSLN proved that it could indeed better the lives of Nicaraguans. However, as the counterrevolution progressed, the Sandinistas’ ability to improve or even protect lives rapidly deteriorated. When Hurricane Juana hit in 1988, leaving 180,000 people homeless, the war-ravaged country and flailing Sandinista government could not cope, and support plummeted further as elections drew near.

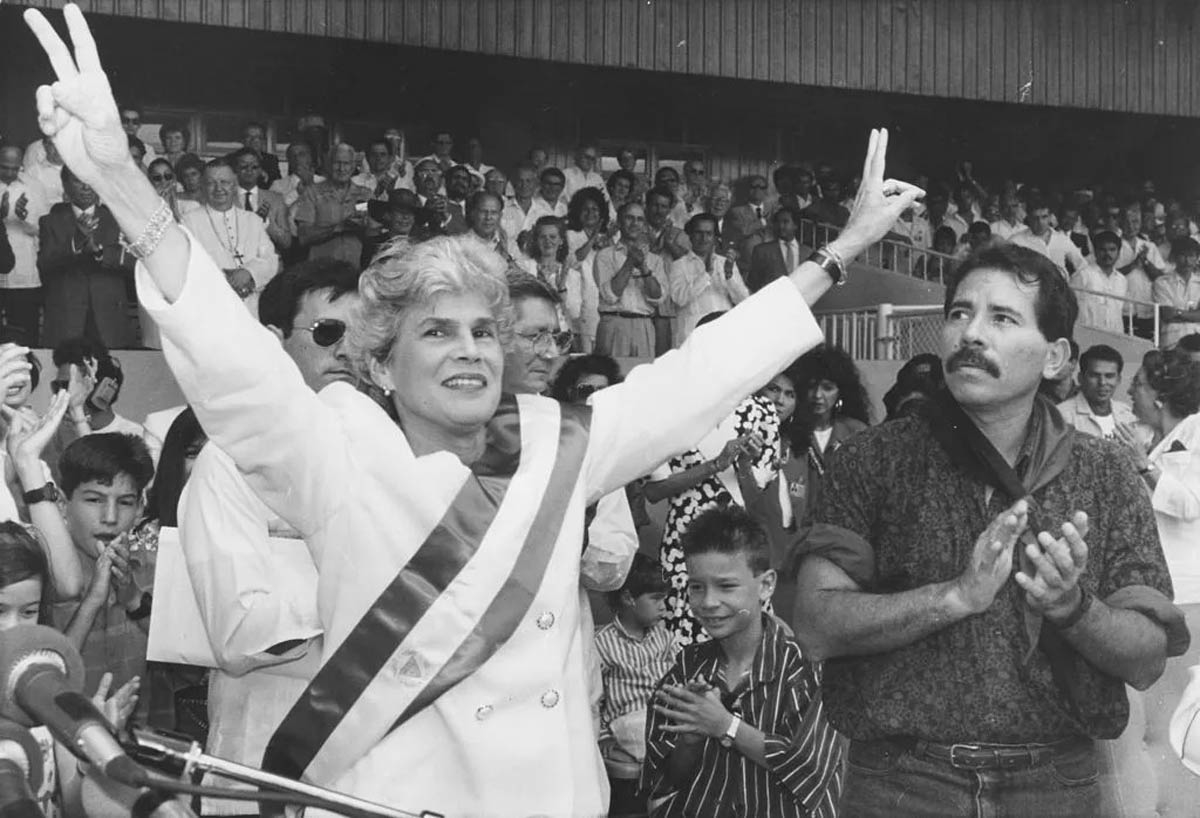

In 1990, Violeta Chamorro, widow of murdered La Prensa editor Pedro Joaquin Chamorro and one-time member of the post-Somoza junta, ran for president as part of an anti-Sandinista coalition and won in elections determined to be free and fair by nonpartisan international observers. The coalition, orchestrated by the US, had given the Nicaraguan people a choice: the Sandinistas or an end to the war.

It’s noteworthy that the Sandinistas could have employed a number of tactics to remain in power, as seen so often in neighboring countries. They might have delayed elections because of the circumstances or refused to recognize the elections as valid because of US interference. Instead, they accepted the outcome of the elections and allowed a peaceful transition of power, becoming an opposition party in a participatory democracy… at least for a few election cycles. The Sandinistas, still under the leadership of Daniel Ortega, won the presidency again in 2006. Ortega remains in power today.

Additional Sources:

Skidmore, Thomas E and Smith, Peter H. Modern Latin America. Oxford University Press, 2001

Prevost, Gary and Venden, Harry E. Politics of Latin America: The Power Game. Oxford University Press, 2002