We shape our lives based on morality, but have you ever wondered where it comes from? In Genealogy of Morals, Nietzsche examines what we typically consider good and evil, aiming to pull them apart. This groundbreaking work, first published in 1887, argues against the idea that moral values are handed down from above or can be derived through reason. Instead, Nietzsche posits that these values stem from conflicts of power, the ways people have been psychologically manipulated into accepting them, and deep-seated feelings of resentment. Let’s explore this in detail.

Nietzsche’s Historical Approach: Morality as a Cultural Construct

Most philosophers, previous to Nietzsche, had attempted to defend what morality should be—whether of reason (as Kant believed) or of utility (as believed by Bentham and Mill). But Nietzsche turned the inquiry around altogether. Instead of asking what is right, Nietzsche asked: where is morality coming from?

Published in 1887, Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals is contrary to the belief that values are universal or absolute. Instead, he treats them like cultural items created by power relations, psychology, and historical forces. That is his genealogical approach—without assuming that there is absolute morality, but observing how it evolved through history.

Think of Darwin’s evolution theory—how species evolve to survive—Nietzsche held that values evolve within social and historical contexts, too. Warrior cultures’ old values of power, pride, and domination were condemned by religious-based values that promoted humbleness, submission, and guilt.

Nietzsche’s radical insight? Morality is neither passed on by god nor by reason—powerful people make it up to serve their interests. That means that our values today might not be nearly as natural or good as we assume. And if people make up morality, do we have the right to challenge it and redefine it? That’s where Nietzsche shakes everything we assume at face value.

Master vs. Slave Morality: The Birth of Moral Values

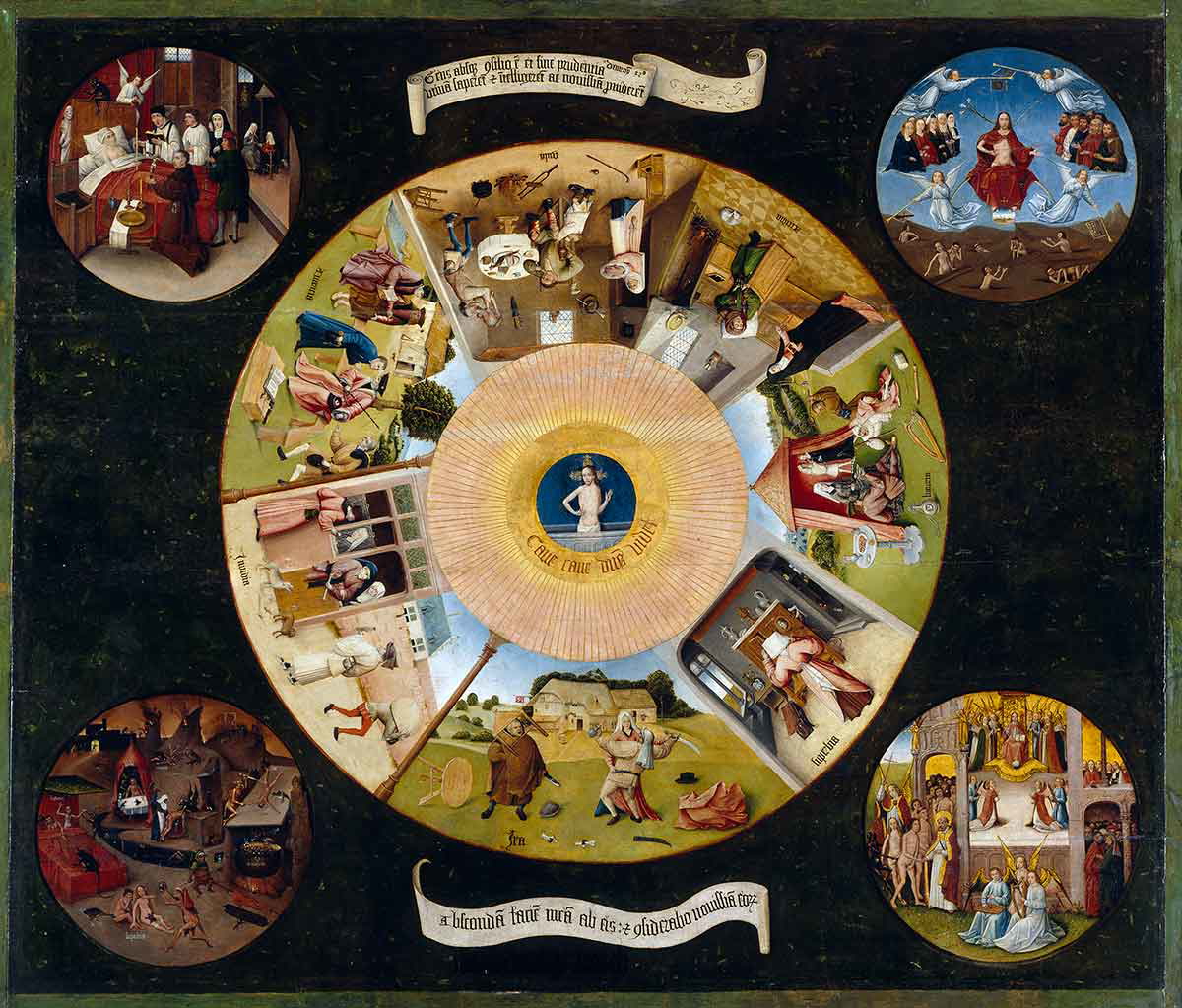

What if good and evil were not universal facts but products of individuals holding power? Such is Nietzsche’s argument in Genealogy of Morals. Nietzsche traces morality to two conflicting schemes of values: Master Morality and Slave Morality—two developed by two different types of people.

Master Morality is passed on by the great, strong, and powerful—ancient society’s aristocracy, rulers, and warriors. Self-assertion, excellence, courage, and strength were values that they held.

Power, health, and domination were what constituted “good” to them, while weakness or defeat constituted “bad.” Think of the Greek heroes like Achilles—ambitious, unafraid, and unashamedly proud.

Then came along Slave Morality, created by the powerless—those weak, bitter, and downtrodden people. Instead of happily taking lower ground, they rearranged morality to make it desirable that they were in that situation.

Weakness is now “virtue,” misery is now “holiness,” and submission is now “goodness.” Рumility, meekness, and obedience were elevated here—traits that suited the powerless but restrained human power.

Nietzsche saw Christianity as the ultimate triumph of Slave Morality. It had converted pride into vice, power into cruelty, and misery into salvation. Instead of honoring heroes, morality had begun honoring martyrs.

The only question Nietzsche invites us to ask is: are our values truly our values, or have we unknowingly inherited a morality that is supposed to make us weak?

The Psychology of Resentment (Ressentiment)

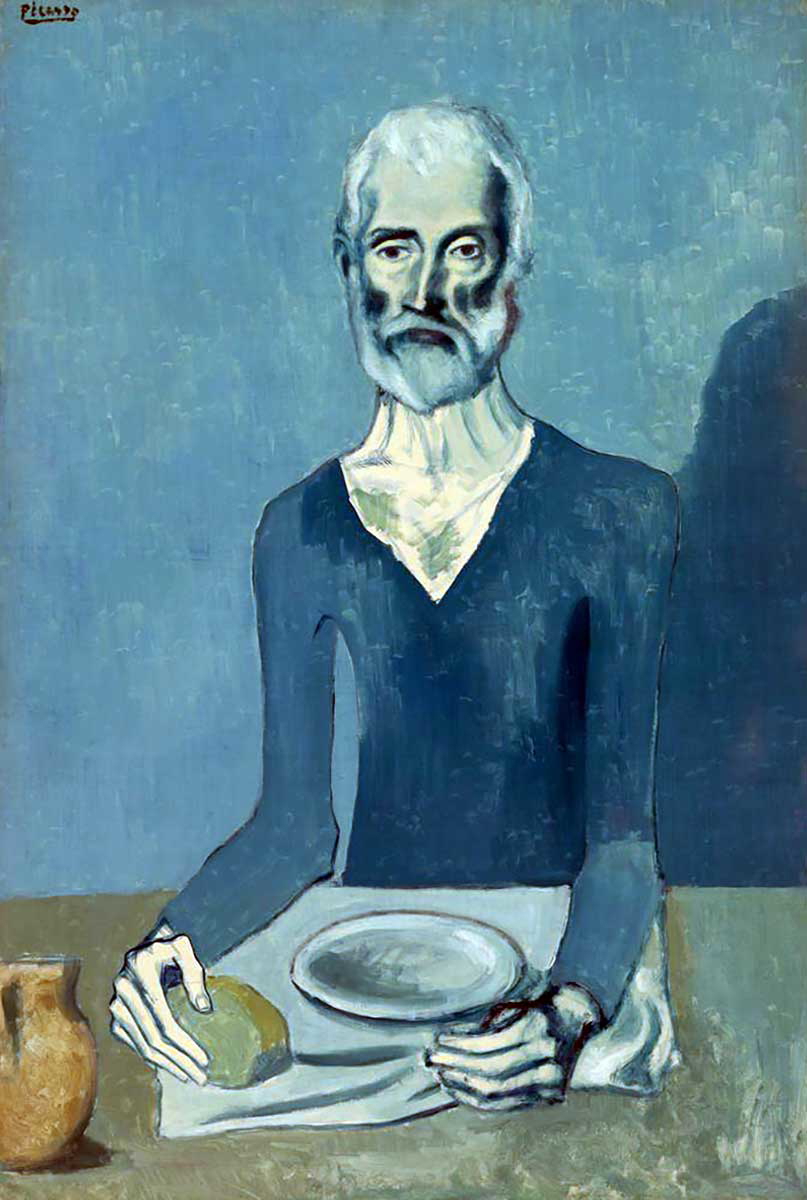

Have you seen how people make weakness into a badge of honor—no, not through pride, but through resentment of individuals of power? That is what Nietzsche’s concept of ressentiment is really all about. It is not anger or jealousy—no, it is bitter, festering resentment of individuals of power that makes individuals of weakness redefine what is good or right.

This is the emotional basis of Slave Morality. The weak do not merely resign themselves to where they are—no, they reverse things around, making wretchedness good and demonizing power.

The Roman Empire, for instance, prized strength, heroism, and conquering. But when Christianity expanded, those very same values were reprehensible—pride is now a vice, humility is now good, and martyrdom is elevated. The very notion of morality itself was redacted—not by power brokers, but by people who hated power.

And this is no mere history of old times. Nietzsche’s criticism remains valid today also. Political grievances, ideological struggles, and victim culture are manifestations of the same dynamics of ressentiment—groups defining goodness in terms of bitterness against what is regarded as dominant or powerful. Some movements opt for power through weakness rather than greatness.

Nietzsche’s challenge is ominous: are we building our values on power, or are we letting bitterness taint our view of reality?

Guilt and Bad Conscience: The Internalization of Punishment

Ever felt guilty of doing or saying anything, no matter that there is no one there? That’s a bad conscience, and Nietzsche writes that it wasn’t originally part of our nature—our society implanted it in us.

Originally, morality had no relation to inner guilt but only to repayment. When you offended somebody in earlier cultures, you weren’t guilty—you owed compensation. When you stole, you compensated doubly. When you hurt somebody, you compensate them. Morality had to do with balancing things out, not shame.

But as civilizations evolved, punishment turned inward. No longer were individuals policed by outside consequences, but by individuals policing others. Laws, religion, and social norms are ingrained within individuals, so that there are things that are “wrong” within our very hearts.

Christianity had much to do with this—no longer were individuals merely paying off debts, but were told that they were innately sinful and had to bear punishment to purge themselves of it. Guilt had grown spiritual, making individuals police others out of fear of punishment rather than out of outside consequences.

Nietzsche’s critique is strikingly similar to that of Freud’s superego—both of them see morality as an inner force that controls people’s actions. However, Nietzsche’s is unmistakable: is guilt actually moral, or is it only helpful in making people compliant?

What if we were unencumbered by unnecessary guilt and were free to set our values? That’s what really gets challenged.

Ascetic Ideals and the Will to Power

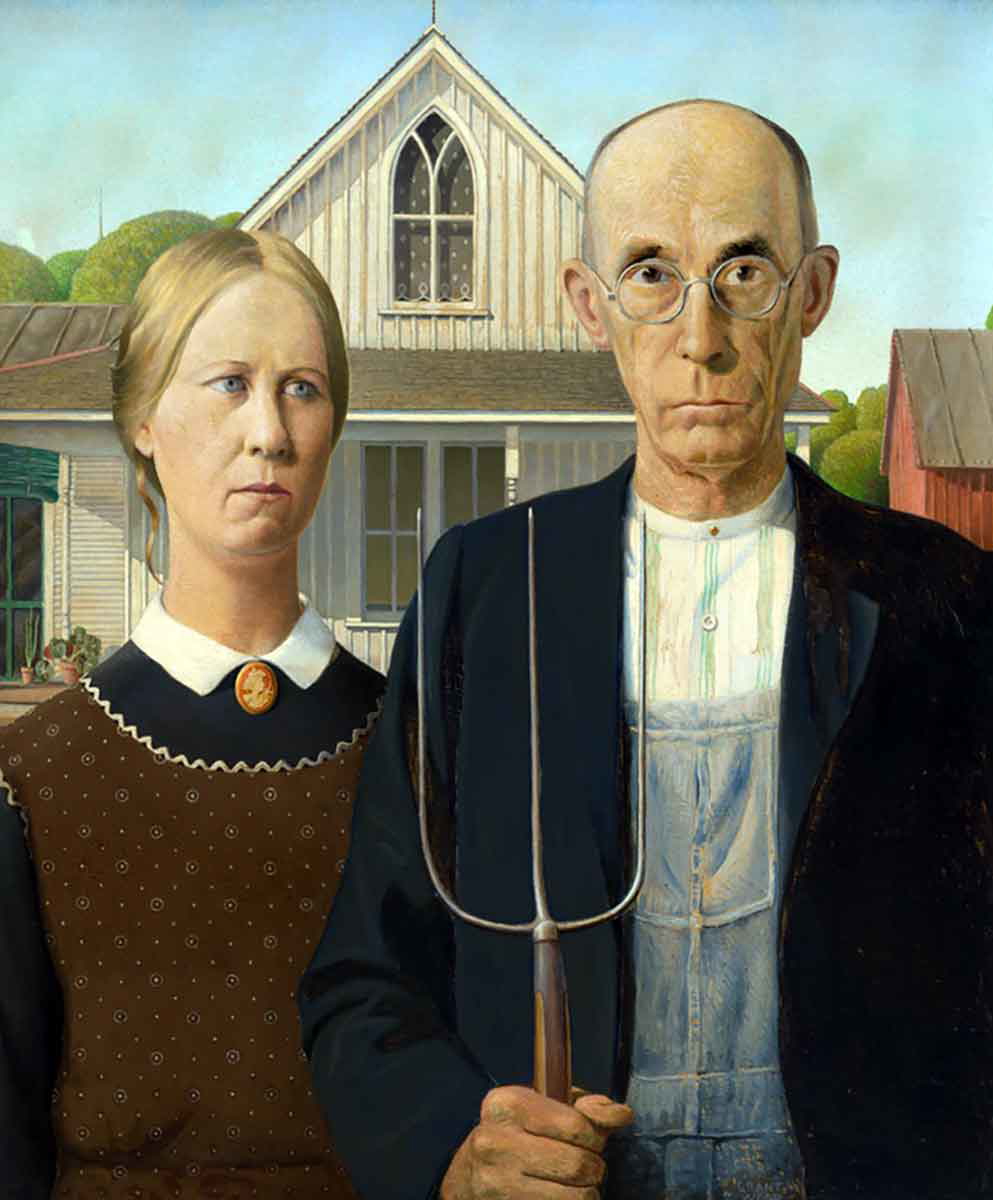

Nietzsche believed that moral codes often promote suffering, sacrifice, and the refusal of pleasure, values he called “ascetic.” Whether they were religious monks seeking purity through fasting or modern professionals who think emotions cloud judgment, many influential people have been guided by such ideals for centuries.

Yet, what if this painful way of life benefits only those who preach it? In his polemic Genealogy of Morals, Friedrich Nietzsche accuses priests and others with a vested interest in an ascetic lifestyle of swindling us all.

Far from enhancing our lives, he argues, their values make both strong and weak people ill-disposed toward vital, humane activities.

Nietzsche presents another option: the will to power. Instead of suppressing our desires, we ought to harness our energy for constructive ends—to be creative, grow stronger, and surpass ourselves.

Today, this view has lost none of its force. You have only to look around you: lots of extreme dieters (or fans of minimalism as a lifestyle choice), plus many others drawn to ascetic political doctrines that glorify the virtues of suffering for a cause.

Are such people limiting themselves because it feels empowering to do so, or just following orders that happen to serve an ideal involving lots of pain?

If your answer leans towards the former, then Nietzsche has something he’d like to share with us! Live boldly and well—that is what he urges by inviting all human beings to partake in the will to power.

The Legacy of Genealogy of Morals in Philosophy and Beyond

Rarely does a book come along that rocks the moral world. Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals didn’t just change philosophy—it altered how we think about right and wrong altogether.

When it comes to philosophy, existentialists and postmodernists really ran with Nietzsche’s ideas. Michel Foucault used his genealogical approach to break down how power works in institutions; Gilles Deleuze looked at the ways morals help shape us; Jacques Derrida questioned whether there’s such a thing as fixed moral truth.

What these people saw in him was clear: morality isn’t something that’s been there forever; it changes all the time, and is often manipulated by powerful people anyway.

In the field of psychology, Freud and Nietzsche both suggest that we feel guilty because, deep down, we think we should be punished—we have taken on board society’s moral rules.

Jung takes a different view: he believes that if we feel guilt or shame, we have an opportunity to learn more about ourselves. This process of self-discovery he calls “individuation.”

Nietzsche’s ideas have always been controversial. Some people say that if you take them seriously, it means there can be no such thing as right or wrong (“moral relativism”). Others worry they lead to selfishness, with individuals thinking only of themselves, behaving like “lone wolves.”

But his books are still read today. In a world where leaders may justify wars or unfair economic policies by reference to what God wants or what a dead philosopher once wrote, Nietzsche makes us ask: why do we believe these things just because they’re old?

So, What Is Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals About?

Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals is a major work of philosophy that challenges everything we believe about being good people.

He shows how ancient ideas about right and wrong were based on strength and a feeling of saying “yes” to life, until they were overthrown by a different way of thinking. By making self-control a virtue too, they found a way to control others: guilt.

And we have all inherited this way of looking at things, whether we know it or not. Instead of encouraging us to grow and change, our moral code tells us to stay in line and keep things exactly as they are (even though the people who came up with it did no such thing).

So, where does that leave human beings? Are we free individuals with minds of our own, or have we just not realized we’re obeying rules that stop us from reaching our full potential, like an animal trained not to do cool tricks by being scared whenever it tries something new?