Nietzsche acknowledges the debt owed by Western societies and cultures to Christianity, but he also believed the religion was responsible for spreading dangerous misinformation about life. He anticipated that one day people would no longer believe in what he considered to be the lie of Christianity. This loss of belief he expressed poetically as the death of God. However, Nietzsche was not interested in the destruction of belief but in the creation of new belief and the emergence of new values. This creative aspect is often missed by his readers.

Is God Dead?

“God is dead! God Remains dead! And we have killed him!” So wrote Friedrich Nietzsche in his 1882 text The Gay Science. There are some points that need to be made right from the outset about this shocking claim. First of all, in the text these are not Nietzsche’s words but come from the mouth of a character referred to as ‘the madman.’ And so it could be interpreted that the idea that God is dead comes from the ravings of a madman; in other words, one would have to be mad to believe that God is dead. Indeed, in the relevant section of The Gay Science all those who hear the madman’s word do believe him to be insane and mock him for his ideas.

A second point worth making is that if we look closely at the words, Nietzsche is not talking about the non-existence of God but rather a possible no-longer existence of God.

In other words, the madman is not claiming that God does not exist (and never had) but rather that he once existed but is no longer alive: God is dead.

Now, the belief that there is not God and there never has been is held by atheists. In Nietzsche’s text, the madman is addressing atheists. That is, he is telling non-believers that they (and himself included) have ‘killed’ God. What does he mean?

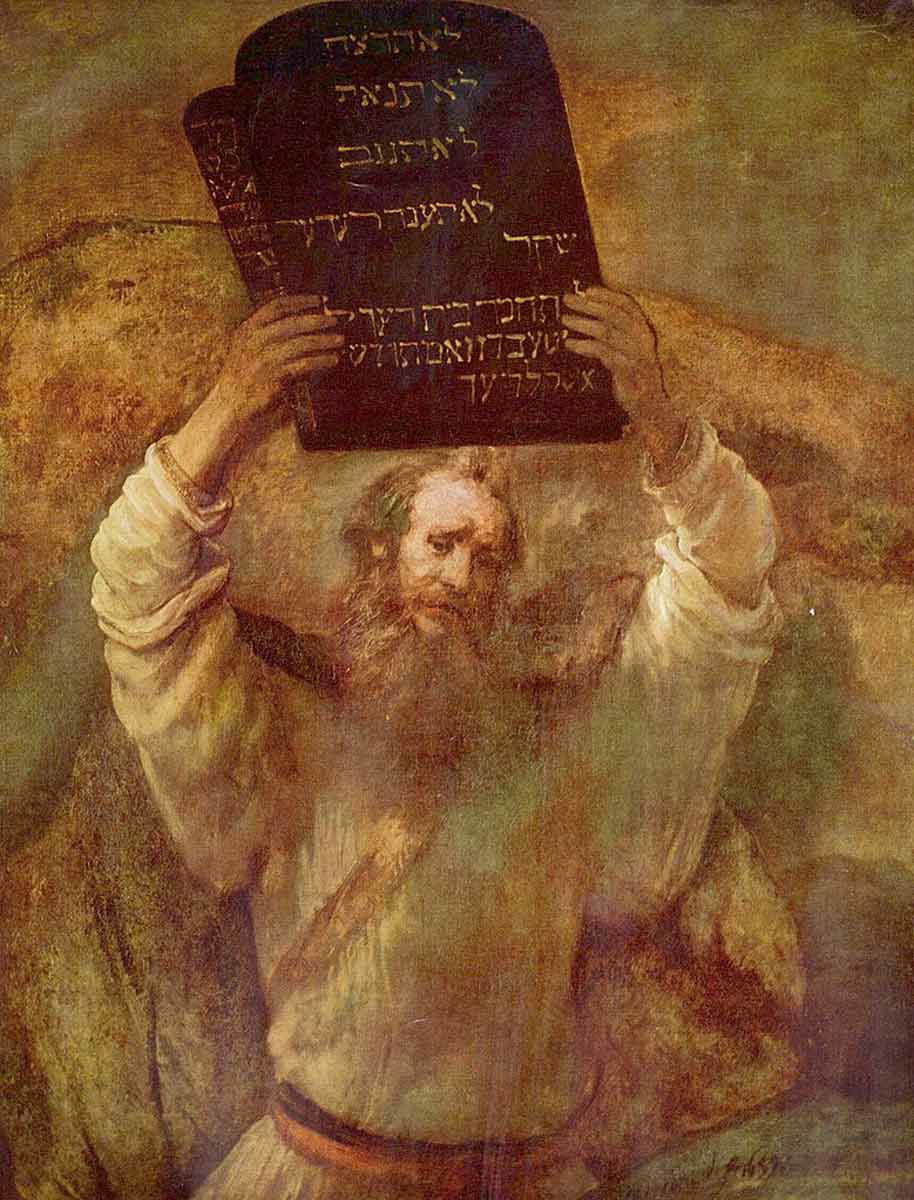

The God the madman is referring to is the Judeo-Christian God, and if this deity exists then He cannot be killed. The idea of literally killing God is preposterous. One might be tempted to think that this is why Nietzsche chose to call his character ‘the madman’ but, as we shall see, he has another idea in mind. What the madman is actually talking about is belief in God.

The Shadow of God

To better understand Nietzsche’s point and what his madman is saying, let us take a close look at the text. The Gay Science is a collection of aphorisms in five sections or books. The work was published in 1882 with the fifth section added in 1887. The aphorism we are interested in is number 125 and is found in the third book, which begins with aphorism 108:

New battles. – After Buddha was dead, they still showed his shadow in a cave for centuries – a tremendous, gruesome shadow. God is dead; but given the way people are, there may still for millennia be caves in which they still show his shadow. – And we – we must still defeat his shadow as well! (GS 108)

Here Nietzsche begins by mentioning a new battle to be fought and ends with the idea that ‘we’ must defeat God’s shadow. Included in this ‘we’ are atheists, those who do not believe in God. The ‘shadow of God’ is the legacy of Christian belief.

Nietzsche’s point is that even if everyone stops believing in God, Christian ideas still prevail. The memory of Christianity will still cast a long shadow over society. In Christian countries our sense of right and wrong originates from religion. Without recourse to God to defend our ideas, we have no reason to hold our moral views.

To continue living after rejecting Christianity, we must either develop new beliefs or justify the old ones. That is, ideas of right and wrong that were previously justified by a belief in God will have to be reevaluated. This reevaluation is the new battle Nietzsche is referring to.

The Madman

The aphorism we are most interested in—aphorism 125—begins with Nietzsche asking if we have ever heard of the madman who turned up at the marketplace looking for God. Despite it being daytime, the madman has a lamp to help him find God. He is saying that he is looking for God, not that God is dead. “I seek God! I seek God!” he cries as he rushes around the marketplace.

Here, Nietzsche is alluding to the Greek philosopher Diogenes of Sinope. Diogenes was an eccentric character who lived in a barrel in the marketplace at Athens. He saw it as his mission to criticize and subvert traditional and political ideas. One famous story is that he would walk about during the day with a lit lamp and when asked why, he would answer that he was looking for a man. Nietzsche, a classical scholar as well as a philosopher and social critic, is using this imagery to suggest that his ‘madman’ is subversive and a social critic.

In the aphorism, Nietzsche says that many people in the marketplace do not believe in God and begin to mock the madman. Joking at his expense, they ask if God has gotten lost or is afraid of people and hiding from them. Suddenly the madman jumps up and down and cries out the now famous lines that “God is dead and that we have killed him.” It is at this point that it becomes clear that the madman is talking about the death of belief in God rather than the actual death of a god. This is why Nietzsche has him addressing the atheists in the marketplace. Nietzsche’s point is that atheists think that it is enough not to believe in God but don’t realize that, without God, they must reinvent society.

Let There Be Light!

The madman marvels at the enormity of what it is to no longer believe in God:

“We have killed him – you and I! We are all his murderers. But how did we do this? How were we able to drink up the sea? Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon? What were we doing when we unchained this earth from its sun? Where is it moving to now? Where are we moving to? Away from all suns? Are we not continually falling? And backwards, sidewards, forwards, in all directions? Is there still an up and a down? Aren’t we straying as though through an infinite nothing? Isn’t empty space breathing at us? Hasn’t it got colder? Isn’t night and more night coming again and again? Don’t lanterns have to be lit in the morning?”

Once he has established the enormity of what has happened, he moves on to what must be done next:

“How can we console ourselves, the murderers of all murderers! The holiest and the mightiest thing the world has ever possessed has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood from us? With what water could we clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what holy games will we have to invent for ourselves? Is the magnitude of this deed not too great for us? Do we not ourselves have to become gods merely to appear worthy of it? There was never a greater deed – and whoever is born after us will on account of this deed belong to a higher history than all history up to now!”

What the madman is saying is that a new religion must be created to replace Christianity, which has been lost.

Stumbling Around in the Dark

Galileo once said that without the language of mathematics to guide us, human existence is like stumbling around a labyrinth in the dark. Nietzsche’s madman is saying something similar but he is referring to what we might call the language of Christianity.

Christian ideas are not just a collection of stories about long-ago events (that may or may not have actually happened) along with a set of rules by which we ought to live. Christianity has provided not only an account of why we are here and what the world is all about but what it is human beings are supposed to be doing with life.

Science provides us with knowledge but only of a certain kind. Using Nietzschean terminology, science gives us answers to ‘how questions’ but not to ‘why questions’. For example, science tells us how the human body uses oxygen and how much oxygen we need in order to live; but it cannot tell us why we ought to live. That is, science can tell us what life is, what it is for something to be considered alive, but it cannot put a value on life. Science says that if a living thing is deprived of oxygen, it will die—but it cannot tell us why it might be wrong to deprive a living thing of oxygen.

In Twilight of the Idols (1889), Nietzsche says that as long as we have the why for our lives, we can get by with any how. He meant that in order for human beings to live and flourish, we need answers to the kinds of questions put to religions.

In aphorism 125, the madman is ‘mad’ because, without Christianity, we no longer have the answers we need to live our lives. But there is also reason for hope!

What Holy Games!

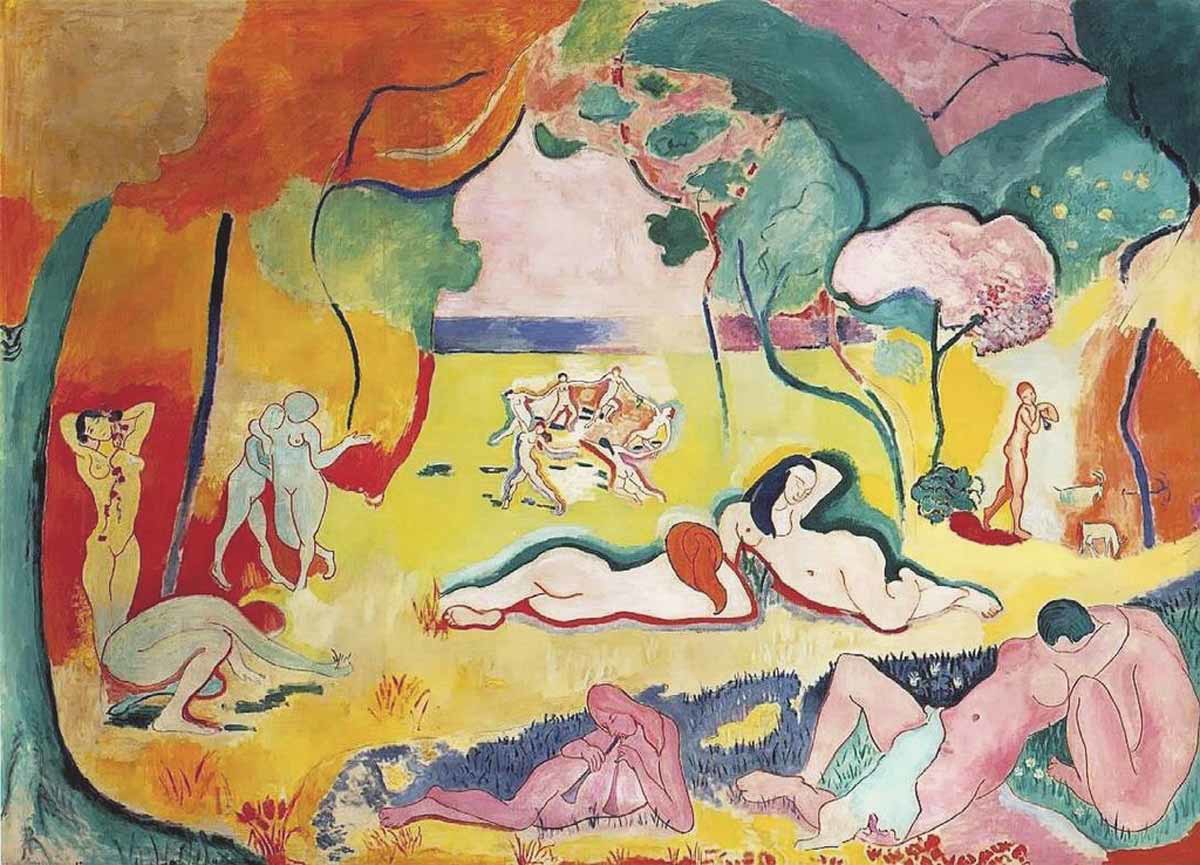

After almost despairing over the loss of orientation now that Christianity has been lost, where up might as well be down and left be right, night be day and so on, the madman moves on to the much-needed discovery of new values. He asks what religious festivals and holy games we will have to invent. There is the suggestion that not only will new gods have to be invented, but that future generations will come to think of the people of today as actually gods themselves.

Nietzsche was very interested in the new science of anthropology. In his possession, he had several annotated textbooks, and ideas from these works appear in his text. Something that intrigued him is how ideas in the form of what we might call ‘social memories’ were passed down through the generations. In addition, Nietzsche also had a related interest in the phenomena of ancestor worship. Put simply, he was fascinated in the process by which societies come to accept particular ideas as sacred and inviolable.

In short, he believed that violent and painful religious rites and ceremonies (holy games) cemented people’s ‘memory’ that certain things are valuable. These ideas become a group’s set of shared ‘values’. A society without values cannot survive, and so existing generations owe a debt of gratitude to their ancestors, who instilled the group’s value system. This acknowledgment of a debt, the need for gratitude over time, becomes ancestor worship, whereby ancestors come to be seen as gods.

In aphorism 125, the madman claims that because God is dead and we no longer believe in Christian claims about life and existence, we need to create a new set of beliefs for ourselves and future generations. Nietzsche believes this ought to be a joyful discovery.

The Joyful Wisdom

Nietzsche’s The Gay Science is published in the original German as Die fröhliche Wissenschaft. It can be translated into English as The Gay Science and also as The Joyful Wisdom. Nietzsche writes about things he believes ought to be seen as reasons to be joyful. For example, the idea that ‘God is dead’ is a reason to be joyful.

Nietzsche had a complicated relationship with Christianity. He was brought up in a religious household and was very familiar with Christian theology. Indeed, his work is filled with Christian references. Although he was an atheist, he acknowledged our debt to religious belief.

Without Christianity life would have been impossible. Trying to navigate life would have been like stumbling around Galileo’s dark labyrinth. However, despite acknowledging this debt, Nietzsche also believed Christianity spread dangerously wrong ideas. In addition—for reasons beyond the scope of this article—Nietzsche thought Christianity had a kind of inbuilt self-destruct mechanism that would, eventually, cause all believers to lose faith. He was concerned about what would happen when that time came. How could people cope with such a loss of value and meaning in their lives; suddenly finding themselves alone in a dark labyrinth?

Nietzsche also saw the increasing loss of belief in Christianity as an amazing opportunity to create a new, better religion to replace it—one without the flaws of Christianity. He saw this opportunity as joyful.

This opportunity is so often missed in people’s reading of Nietzsche. They see his denial of God’s existence and perhaps glee at widespread loss of faith, but they miss his joy at having the chance to reevaluate and reinvent our shared values.