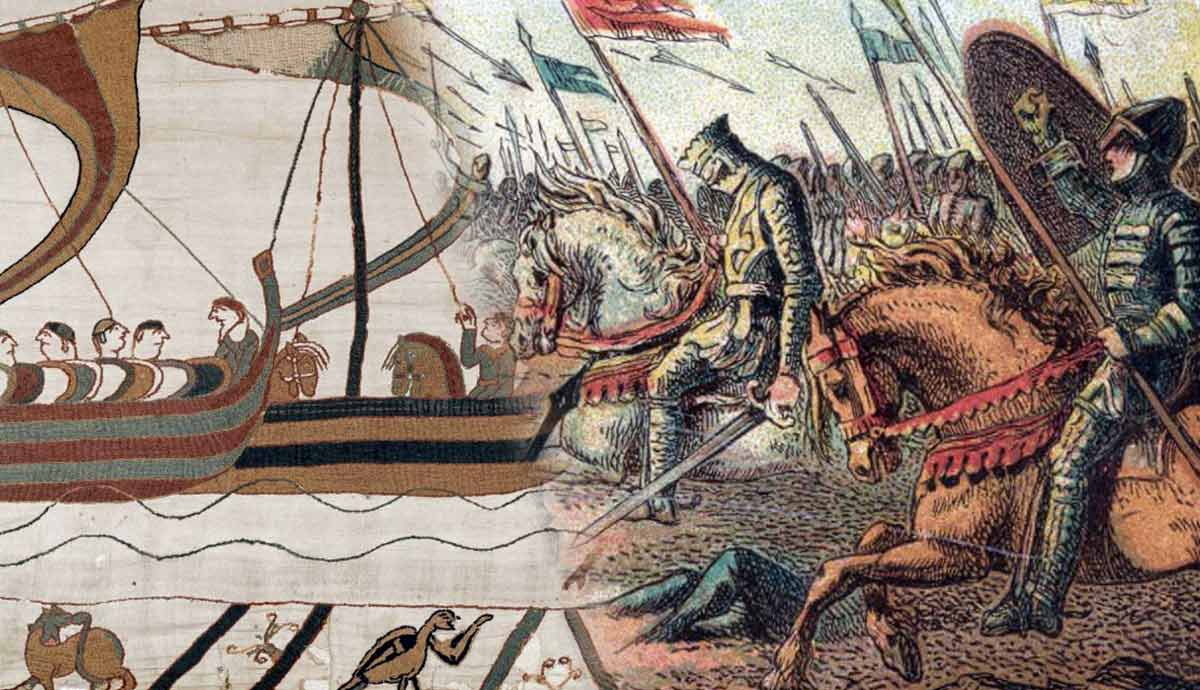

Many people may not be aware that the governments of France and England were once closely linked, including through a single monarchy. In 1066, William, Duke of Normandy, invaded England to avenge the affront of not being named King of England, as he had been promised. The strategically planned invasion of England from France remains the last successful conquest of the island nation. Ultimately, William’s invasion, giving him the nickname William the Conqueror, gave him ruling power in both England and parts of continental Europe. Between 1066 and his death in 1087, William the Conqueror presided over significant political and social changes in England, all while facing many military challenges from rivals.

Setting the Stage: 11th Century England

Prior to 1066 CE, England had been a kingdom for about 150 years and was composed of a mix of Anglo-Saxons and descendants of Vikings. Between 990 and 1042, control of England jumped between Norsemen and Anglo-Saxons. In 1042, Anglo-Saxons reclaimed the throne with King Edward the Confessor. He would be the last ruler of Anglo-Saxon England, which succeeded Roman Britain when the Roman Empire collapsed in the 400s. During the Anglo-Saxon era, Britain was actually warmer than today due to a different climate pattern, making the island nation desirable for invaders.

The Anglo-Saxons were a combination of Germanic-speaking tribes who arrived in England from continental Europe, beginning during the Roman era. Fabled tales like King Arthur are reportedly about the Romano-British fighting against these “barbarian” invaders circa 500 CE. For about 300 years, during the influx of the Anglo-Saxons, England was broken into several smaller kingdoms. Thus, England was not a long-established and unified nation for many generations prior to the Norman invasion, as opposed to our contemporary view today of Britain having a lengthy, unified history.

Setting the Stage: Royal Drama and Intrigue

Most of Europe during the Middle Ages utilized the feudal system to organize economic production and security. Various lords and barons controlled feudal estates, or mini-kingdoms, and rendered fealty (loyalty) to a king, to whom they paid taxes and provided soldiers in times of crisis. The concept of hereditary rule prevailed throughout much of Western and Central Europe, with titles and land holdings passing from father to son. This could lead to drama and intrigue if the lineage was complicated, such as multiple sons, no son, or the son being too young to take control of the assets upon his father’s death.

The complexity of lineage in regard to laws of inheritance could lead to conflict among male descendants of a deceased lord… or even a king. During this early Middle Ages era of feudalism, also known as the Dark Ages, the Normans (people from the Normandy region of France) were expanding their influence. These descendants of Scandinavians began to spread outward from Normandy around 1000 CE due to overcrowding, which was a significant issue regarding land inheritance when a lord had many sons. By the 1030s, the Normans were invading the kingdoms of Italy, through which they would continue southward, eventually seizing Sicily.

1065: King Edward the Confessor Incapacitated

In 1065, the king of England was Edward the Confessor, who had been on the throne since 1042. Edward was the eldest surviving son of King Aethelred “the Unready,” and his mother, Aethelred’s second wife, was the sister of the Duke of Normandy, in France. Aethelred died in 1016, and his eldest son from his first marriage was killed fighting Cnut the Great of Denmark, who took the throne of England for himself and married Aethelred’s second wife. After Cnut’s death, it took seven years for Edward to be named king, and only after his brother, Alfred, was murdered.

Edward had been living in exile in Normandy while the Danes under Cnut the Great controlled England. Without sons of his own, Edward gave lordships to the sons of three powerful earls in England who were much-needed allies. In 1053, one of these sons, Harold, succeeded his father as earl. A few years later, Edward began searching for male relatives to succeed him, only to have one die shortly before making it back to England. In the autumn of 1065, after visiting the Northumbria region in the north of England, Edward fell ill and was incapacitated. While he lay ill, St. Peter’s Abbey at Westminster was consecrated, helping secure Edward’s religious nickname due to his fulfilment of his obligation to the Pope.

1066: Harold Godwinson Becomes Harold II

Allegedly, Edward the Confessor gestured on his deathbed in early January 1066 that Earl Harold Godwin, son of his former ally, should succeed him. King Edward passed away on January 5, and Harold Godwinson crowned himself king the next day in Westminster Abbey, becoming King Harold II. He had been hastily elected as king by the Witan, or advisory council of the king. As the likely most powerful man in England, Harold Godwinson was not a bad choice for king, and he was considered quite capable. He was related by marriage, on his mother’s side, to the previous king Cnut the Great.

Despite his strong claim to the throne, Harold II’s coronation was not unchallenged. The King of Norway argued that he had a deal with Cnut the Great, which said the survivor of the two would rule both kingdoms if the other died without an heir (as did Cnut). Harold’s younger brother, Tostig, had been exiled by Harold and plotted his revenge from continental Europe. Quickly, Tostig decided to ally with the King of Norway in their mutual plot against Harold. As the duo planned to invade Scotland, attacking Harold from the north, another challenge loomed in France.

William, Duke of Normandy, Lobbies for the Throne

William, Duke of Normandy, was related to Edward the Confessor’s mother and thus had a lineal link to the throne of England. However, William was allegedly the illegitimate son of Robert, Duke of Normandy, by a common mother. Despite being born in the duke’s castle, William was often labeled a “bastard.” Robert died in 1035 after formally naming William as his heir. His early rule, beginning in 1042 as a young adult, was faced with challenges to his authority, forcing him to fight. Upon marriage to a woman from a powerful family in 1050, William’s rule finally became easier.

The hard lessons William learned as a young duke would later travel with him to England, where Harold II’s new rule was not without controversy. Harold II was not biologically related to Edward the Confessor and had been chosen as king by the Witan due to his status as England’s most powerful earl. Allegedly, however, Harold had pledged the throne of England to William, Duke of Normandy, two years earlier, when he had been shipwrecked there. Now, William wanted to collect on that alleged promise. He quickly realized that he would have to take the throne by force.

September 1066: William’s Lucky Landing

Although William quickly assembled an invasion force by July 1066, he did not sail across the English Channel immediately. The Duke needed to give his invasion political legitimacy, which he did by convincing both fellow Norman lords and the Pope in Rome that Harold Godwinson had sworn to William, on holy relics, that he would help the Duke take the throne. Convincing the French lords gave William the ability to source soldiers and supplies from across France, and Pope Alexander II allegedly supported William’s invasion on the promise that he would reform England’s Catholic churches according to the Pope’s wishes.

In late September, William finally arrived in southeastern England with his flotilla of ships. Up to 8,000 men and 5,000 horses were landed, using roughly a thousand ships. Unopposed, they had sailed across the Channel on the night of September 28, 1066. Fortunately for William, the landing on the beaches at Pevensey went unnoticed because King Harold II was busy fighting the King of Norway in the north. Upon receiving word of the invasion, Harold and his army marched south as rapidly as possible. This time was well-used by William to prepare his attack inland.

October 14, 1066: The Battle of Hastings

The two armies finally clashed on October 14, having seen each other for the first time the previous day. Seven miles from the city of Hastings, King Harold’s soldiers claimed the high ground atop the hills, while William of Normandy’s soldiers attempted to push them off. Despite having the high ground, Harold’s men were exhausted from fighting the King of Norway and having to march almost 30 miles a day to combat a new threat. Both armies are believed to have been similarly sized, with between five and seven thousand men each.

Battle commenced at approximately 9:00 AM, with the Normans and their fellow Frenchmen on the offensive and the English maintaining a solid defensive line. At first, the English held firm, and some Normans began to panic when a rumor circulated that William himself had been killed. When William publicly removed his helmet and rode in front of his soldiers to show that he was indeed alive, the French rallied and attacked with renewed vigor. They used a new tactic: pretending to retreat to draw out the English into a pursuit, and then surrounding these pursuers. King Harold II himself was killed late in the day, with the English fleeing by dusk without leadership to rally them.

December 25, 1066: William Crowned King of England

With victory at Hastings, William of Normandy, often known now by the moniker William the Conqueror, was able to march unopposed on London. He was crowned King William I in Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day. Despite William’s swift skill as a conqueror, challenges to his authority quickly arose, similar to his young adulthood in France. Within two years of being king, William faced rebellions, especially in the north. He responded to rebellions by building fortresses and castles.

Between 1068 and 1070, William I faced several challenges, some of which he addressed through a scorched earth policy that involved destroying crops to starve out rebellions, as seen in the infamous Harrying of the North. Despite the controversial brutality, including thousands of starved civilians, the tactics of William I were successful in maintaining his rule. He later showed grace, including building an abbey at the site of the Battle of Hastings as a sign of penance for those who had been killed. Allegedly, the altar was placed on the spot where Harold II died in battle, honoring his foe’s memory.

Political Reforms of William the Conqueror

William I replaced the English landowning elites with his own allies from Normandy, redistributing land for loyalty and military service. However, he did vow to honor the rights of Englishmen who remained loyal and made efforts to signify that he was a rightful heir to Edward the Confessor. He replaced English clergy with Normans, thus following through on his promise to Pope Alexander II. French was made the official language of government, injecting new vocabulary into the English language. As the new elites, the Normans injected French culture and customs into the English government.

The replacement of Anglo-Saxon clergy and officials with Normans introduced new language, customs, culture, and architecture to England. French clergy introduced Romanesque architecture in the form of cathedrals, and William himself made castles with moats, a common military defense strategy. He deviated from previous strategies to build forts out of wood, which rotted quickly and were vulnerable to flames, and instead demanded that they be built out of stone. Most wooden fortresses were rebuilt out of stone, creating new administrative centers for William I’s government.

Administration of William the Conqueror

It was somewhat of a struggle to uphold existing Anglo-Saxon laws, as William I pledged to do, with new Norman laws and Church courts. To maintain order, William increased the power of sheriffs, who took over many powers previously enjoyed by lords. In 1085, William I made sheriffs the official tax collectors, ensuring a steadier stream of revenue that would not be siphoned off by local lords. Appointing loyal officials was important, as William I himself was often not in England, but back in Normandy. He left regents to govern in his stead when he was in Normandy.

Although William I had a firm grip on England by 1075, his power in France began to wane. In September 1076, he was defeated in battle by King Philip I of France while besieging a castle at Dol and forced to retreat back to his territory of Normandy. The next year, William I faced hostility from his eldest son, Robert, which evolved into William besieging Robert’s castle in January 1079. In a surprising route, Robert’s forces sallied out from the castle and defeated William’s siege. Word of William’s defeat sparked new rebellions in England, which he put down. Famously, in 1085, William ordered a mass survey of all his lands and those owned by his vassals (loyal subjects), resulting in the Domesday Book. This likely assisted in tax collection, which was needed for providing military security.

Legacy of William the Conqueror

On September 9, 1087, William I died in France while on a military campaign. William’s legacy after his death was complex, especially given the volume of discontent due to succession struggles. His sons, Robert and William II, fought over control of both England and Normandy. Despite the warfare, William the Conqueror’s successful seizure of England and tying it to his original territory of Normandy created permanently stronger ties between England and France through linked culture and increased trade.

French would remain the official government language in England for three hundred years, with English spoken by commoners but only French being written by courts, officials, and the wealthy class. Only in 1362 did English become the official language of England again, with King Henry IV delivering the first coronation speech in English in 1399. Through his use of stone castles (Norman castles), powerful sheriffs, and active military campaigns, William the Conqueror can be considered part of the shift from the Early Middle Ages to the High Middle Ages.